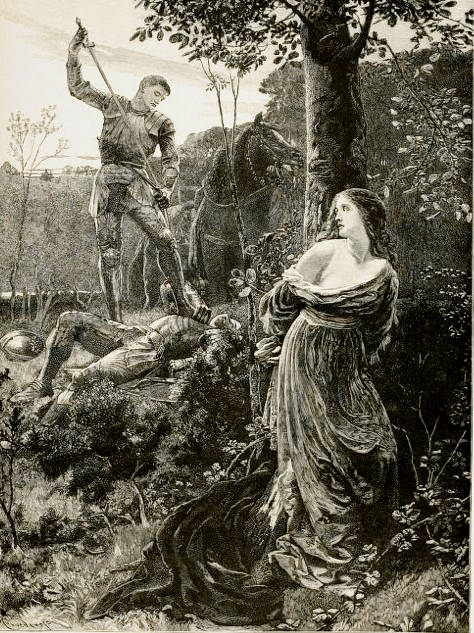

Chivalry

Sir Frank Dicksee, 1853–1928 [?]

Oil on canvas

Source: The 1886-87 Magazine of Art

See commentary below

[Victorian Web Home —> Visual Arts —> Victorian Painters —> Sir Frank Dicksee —> Next]

Chivalry

Sir Frank Dicksee, 1853–1928 [?]

Oil on canvas

Source: The 1886-87 Magazine of Art

See commentary below

You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the Internet Archive and the University of Toronto and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Primarily a piece of decoration, an essay in colour and tone, the original of our frontispiece — Mr. Frank Dicksee's "Chivalry" — has been loudly discussed and persistently misunderstood. If the painter had professed to depict an episode from romance, an incident from the "Idylls of the King," for instauce, little would have been heard of its allegorical character. As it is, his picture has been treated as an allegory pure and simple, an abstract representation of chivalry from the point of view of modern sentiment. Hence it is not surprising it has been generally censured. Allegory the picture is not, but merely a simple and intelligible presentment of circumstances typical of the age of chivalry. It needs no interpretative medium, no special sympathetic insight: only an eye for colour, only a feeling for the plastic qualities of the painter's material. Simple and direct in design, it is far otherwise in execution. The figures are merged in a golden-green light that irradiates the landscape, and this illumination produces a diaphanous effect almost suggestive of a painting on glass. There is a transparency and ethereal brilliancy in the colour which gives the picture a place apart from all others in the Academy. The tree to which the lady is bound, and the woodland scene about her, are more substantial in effect than the figures. These indeed lack something of vitality, of solidity, and character; the victorious knight is almost as void of expression as his foe, who is dead at his feet. He is but an accessory, like the horse, in the decorative scheme of the comjiosition; only in the turned face of the lady, eager to scan her deliverer, have we a touch of the dramatic element needful. The charm of Mr. Dicksee's picture lies in its vague and tender harmonies, in its achievement of a daring and personal invention in colour. His knight has not the martial bearing and virility of the old conception of romance, such as Scott's, for instance; he is Perceval rather, as interpreted by Lord Tennyson and by Wagner, with a touch of Passionate-Brompton thrown in. The lady wants passion and humanity, and is far other than he gallant and fascinating heroines we read of in Percy and old balladry. She would probably involve her rescuer in a metaphysical discussion, as a modern girl might favoiur him with her views on esoteric Buddhism. [464-65]

“Current Art.—IV.” The Magazine of Art. 10 (November 1886-October 1887): 464-70, Internet Archive version of a copy in the University of Toronto Library. Web. 24 October 2014.

Last modified 27 June 2020