Gustave Doré, Master of Imagination is the kind of exhibition that one enters expecting to see old favorites (and one does) but one also continually finds oneself thinking, “I didn't know he did that.” Approaching the National Gallery of Canada's magnificent building, one immediately encounters two different Doré's — the one found in his illustration of a needle-fanged Puss-in-Boots from Perrault's Contes, the other in a sphinx — a detail from The Enigma, a six-and-a-half foot canvas memorializing and mourning the Franco-Prussian War. After walking up the long, long ramp to the second floor. one enters the exhibition passing by a green wall covered with with caricatures from the Journal pour rire, images very different from his later illustrations.

Left to right: (a) Approaching the National Gallery of Canada. (b) A Puss-in-Boots probably too scary for children. (c) The entrance to the exhibition . [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

Turning a corner, one comes upon the unexpected Poem of the Vine (below left) — Doré's thirteen-foot-high, nearly three-ton bronze — which he encrusted with what Paul Lang tells us are 58 putti and many “creatures that menace the grapes” (251). This first gallery has several sculptures by Doré, who was clearly as fine a sculptor as he was illustrator and painter, and as we make our way through the gallery, we discover his often amazing ability to work in so many styles and genres, something set off beautifully by Ellen Treciokas, the exhibition designer, who uses different wall colors for each part of the show.

Left to right: (a) . (b) . (c) Looking from the room with landscapes into that containing Dante and Vergil in the Ninth Circle of Hell. [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

Gustave Doré, Master of Imagination reveals that his oeuvre is so variegated and various that one cannot point with confidence to a characteristic Doré style without immediate qualification. Like J. M. W. Turner, a very different artist, he has multiple styles, but there the parallels with the man who inspired Ruskin to write Modern Painters ends: the Royal Academician, who had a secure place in the art establishment, willingly painted oils and watercolors in his earlier, even old-fashioned style for his more conservative patrons but created wild visions of fog and fire for himself and for the RA exhibitions. In contrast, Doré, an outsider who always wanted to be taken seriously as a painter and sculptor rather than just an illustrator, seemingly wanted to demonstrate that he was an artist who could paint anything better than anyone else and that he could do so in virtually any manner. Certainly, we can point to aspects of style that appear in many of his works, but then one immediately has to turn and point at very different, equally competent works that seem to have been painted, drawn, or sculpted by someone else. Take, for example, his landscapes, which most often employ large horizontal canvases, portions of which plunge into darkness. These works that often take the form something like a Turnerian vortex make the eye rest at a point approximately one third the way from the right or left margins, such as we see in the two paintings of Lock Lomond in the show (1875, numbers 190 [see below] and 191). But then he also paints the very light, high key Scottish Landscape (1873, no. 195) whose trees resemble those found in Edward Lear's Mediterranean works, the brilliant oh-so-Ruskinian Cirque de Gavarnie (n.d., no. 189), and the very different watercolors in vertical formats, The Trou d'Enfer Waterfall in the Lys Valley (192, 1882) and The Alps and Lake Geneva near Glion (n.d., 1879). And that's just his landscapes, which most people who just know Doré the illustrator will here encounter for the first time.

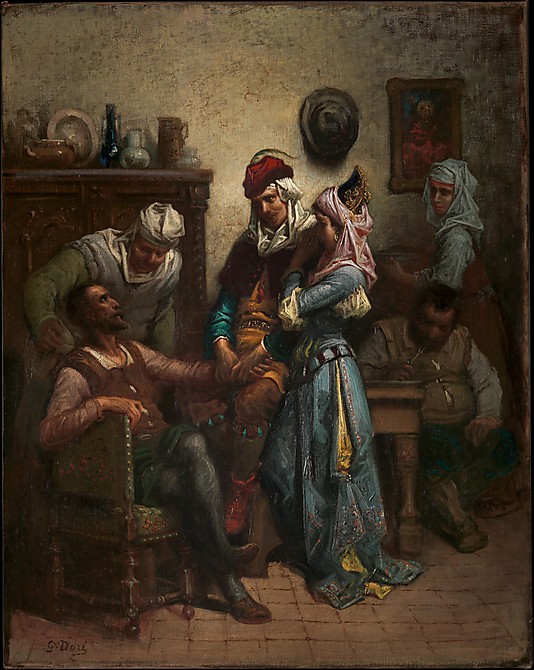

Having briefly glanced at Doré's landscape painting, which is not a genre or subject that one might suspect would appeal to him, next I'll sound like one of those hucksters on late-night American television: “Wait, there's more!” As the exhibition demonstrated, Doré also painted The Oceanids with its plethora of nudes à la Bougereau or Cabanel, Don Quixote and Sancho Panza Entertained by Basil and Quiteria with its completely different color range, the light and delicate Fairy Land (1881, no. 234), monochrome allegories like The Enigma (1871, no. 252), and, of course, canvases like Christ Leaving the Praetorium (1870-80, no. 162, a religious painting he considered his finest work.

Left to right: (a) Don Quixote and Sancho Panza Entertained by Basil and Quiteria. (b) The Oceanids (c. 1878, no. 235). (c) Souvenir of Lock Lomond (1875, no. 190) [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

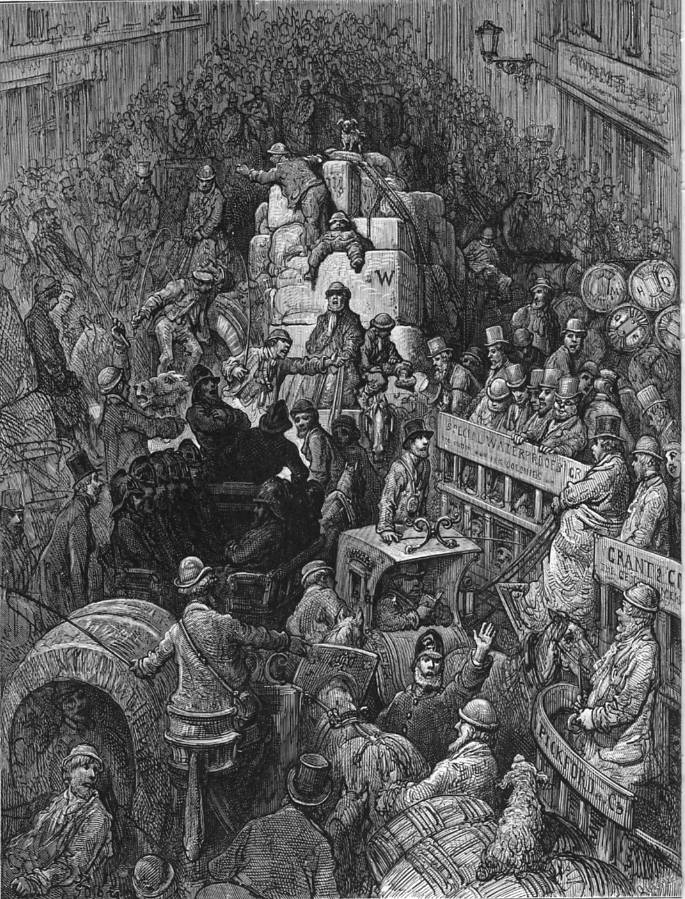

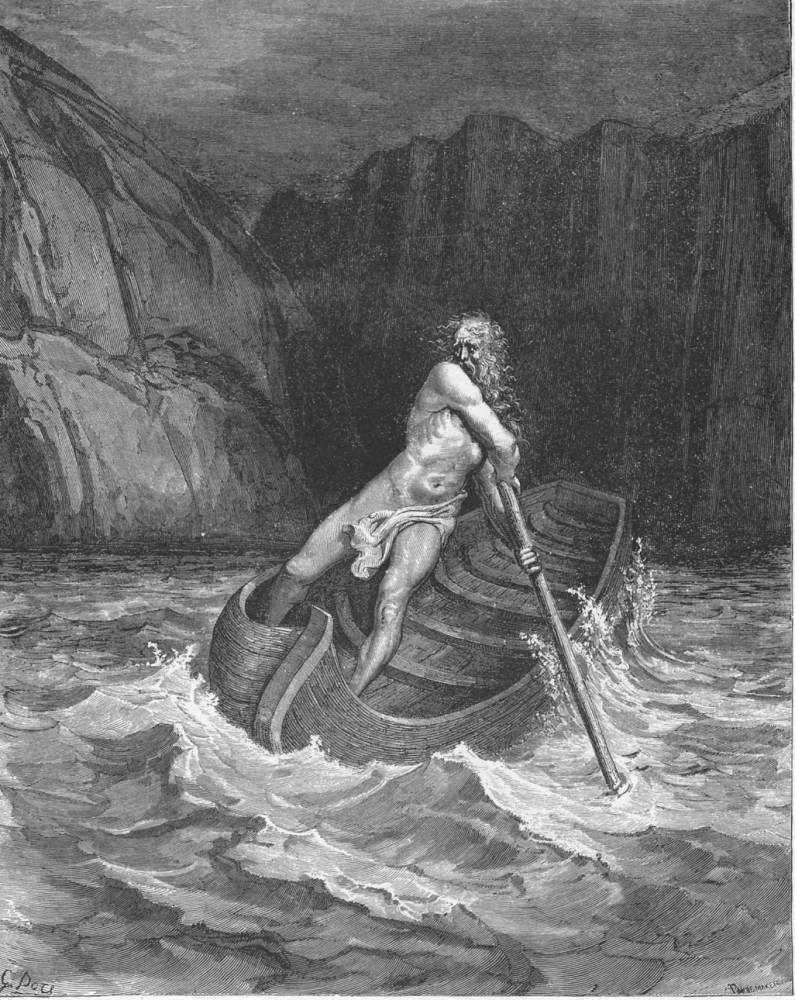

Throughout this amazing range of genres, one can perceive frequently encountered elements — one hesitates to write “characteristics” — in Doré's work, such as his obvious love of plenitude. Many of his paintings and illustrations of subjects ranging from the Bible to Jerrold's London do a wonderful job of portraying crowds, but he also does a brilliant job dramatically presenting one or two figures, something we see in Charon, the Ferryman of Hell, and Farinata degli Uberti.

Plenitude and isolation — Doré's crowds and single and paired figures. Left to right: (a) A City Thoroughfare. (b) Charon, the Ferryman of Hell. (c) Farinata degli Uberti [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

Turning to the subject and tone of Doré's works, we see that many are pervaded by cruelty, something immediately apparent in Between Heaven and Earth, one of the first paintings vistors to the exhibition see. Doré uses a bird's-eye view to depict a frog whose leg is tied to the tail of a kite while the tiny figures below eagerly await the creature's destruction in the opened beak of an approaching bird. As the gallery label points out, the artist remains neutral and does not criticize those enjoying the pleasures of cruelty. Such incidents appear again and again, not only in subjects, such as the Inferno that might seem to demand them but also works like After Dinner at Saulsay (c. 1854, no. 1), in the lower left corner of which two boys assault an old peasant woman. Such an emphasis upon suffering and death pervades many of his great illustrations of Dante and the Bible, where they are by and large appropriate, though the incidents in Dante and Vergil in the Ninth Circle of Hell strike one as more suited to twenty-first-century slasher films than nineteenth-century history painting (see immediately below).

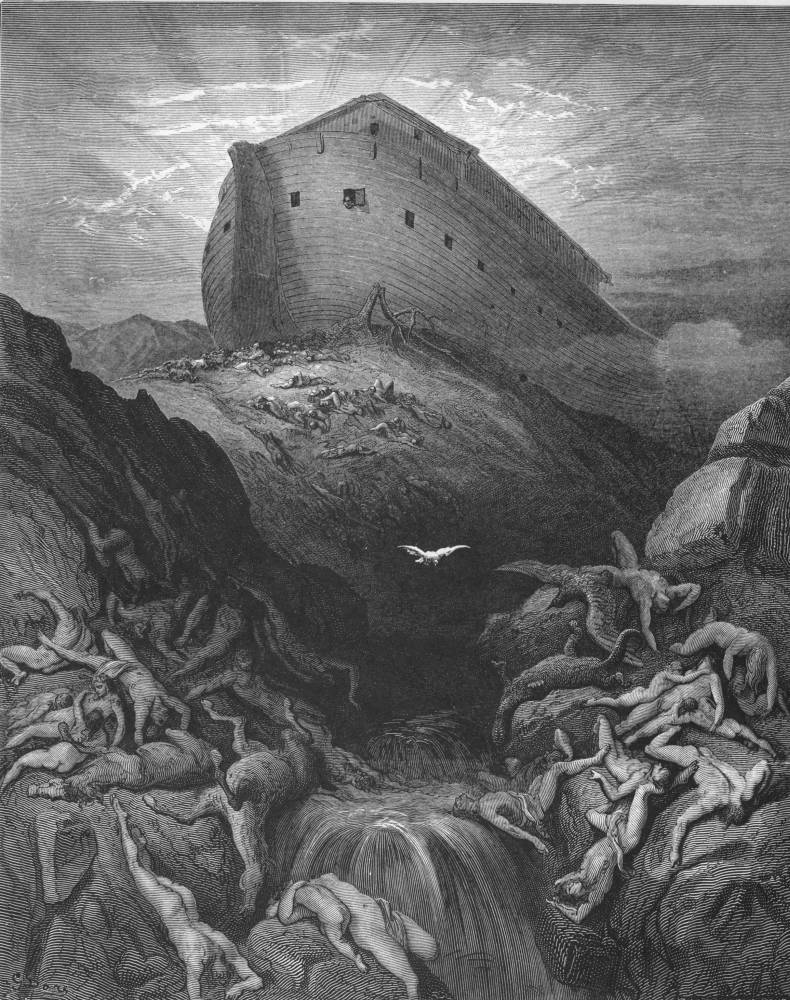

Doré's horrific details: A detail from the lower left corner of Dante and Vergil in the Ninth Circle of Hell. . Right: The Dove sent forth from the Ark. [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

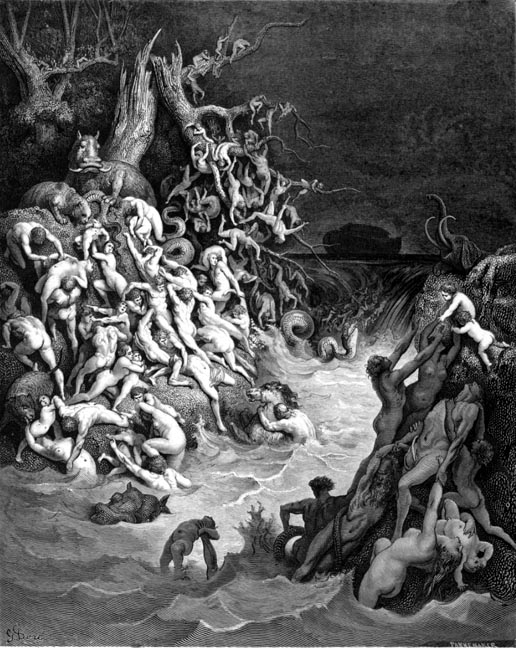

This same concentration on pain and terror often appears in his Bible illustrations. For example, he devotes not one but two plates to showing the terrified, dying victims of the Noachian flood, and in a third he turns away from the oft-painted positive end of that biblical episode when he depicts the Ark at rest after the waters have receded. Doré chooses to show the dove leaving the Ark in search of dry land rather than the common subject of Noah's sacrifice and the answering rainbow. The rainbow, a common subject in stained glass and painting, provides an image of hope — a so-called covenant-sign and a type of Christ. In contrast, Doré's plate shows the landscape beneath the grounded ark littered with the bodies of the impious, punished dead — corpses that, as my wife pointed out, would have long before disappeared into the maws of the creatures of the sea. The brief film clips demonstrating how much European and American cinema has depended upon Doré's illustrated Bible makes his fascination with cruelty and death particularly clear: one early twentieth-century film based on Doré's plate positions the Ark in the distance exactly where the illustration has it, but its mountain sides have no corpses. Meanwhile, in the foreground the film has Noah making his thankful sacrifice after which a pioneering example of cinematic special effects inserts a rainbow over the vessel.

Doré depicts the flood and its aftermath. [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

The exhibition's use of supplemental multimedia

An example of early twentieth-century cinematic version of Dante's Inferno that closely follows Dante and Vergil in the Ninth Circle of Hell (1861, no. 62).

Gustave Doré, Master of Imagination makes a very effective use of multimedia. Three computers permit visitors to page through digital simulacra of books illustrated by Doré, and two projectors convincingly demonstrate Doré's major influence on cinematic presentations of the Bible and the nineteenth-century city, first showing an illustration and then following it by several short film clips ranging from early-twentieth-century cinema to Cecil B. DeMille. In addition to this extremely effective use of projected moving images, the exhibition also includes a documentary presentation of Doré specialists discussing the artist's life and works. Although elegantly filmed and often interesting, the length of the documentary probably would work better on educational television than in an exhibition: most visitors I observed spent a few minutes watching it and then left to look at the paintings and sculpture.

The catalogue

The catalogue of which Philippe Kaenel is both editor and principal contributor serves as an excellent record of the exhibition, placing Doré's work in several necessary contexts. It begins with Kaenel's biography of Doré and a brief commentary on The Street Performers (or The Victim), after which comes David Kunzle's “Caricature and Comic Strip: in and around the Journal pour Rire, 1848-1854.” Then, after several pages of Rabelais illustrations, we have Kaenel's “Imagining Literature,” which is followed by two groupings of plates — eight in a section entitled “Fairy Tales” and nine from Don Quixote. Kaenel's essay, “Spain and London: Visions of Europe,” precedes the first of several one-page commentaries, this one by David Stilton entitled “A Vision of London,” after which come six pages of plates from “London a Pilgrimage” followed by Bertrand Tillier's “The Stylization of History,” which discusses Doré's work on the Crimean and Franco-Prussian Wars. Next, Côme Fabre provides a coda with his brief discussion of The Enigma. Kaenel's essay on Doré's religious painting and illustration — “Preacher Painter: Art, Devotion, and Spectacle” — has two codas, Valérie Sueur-Hermel's “The Neophyte” and Isabelle Saint-Martin's “The Holy Bible” — that are appropriately followed by half a dozen plates from the Doré Bible and eight fron Dante's Inferno. Kaenel's “Landscapes: ‘With his fingers and his imagination’” takes us in another direction, one quite unexpected to those who know only Doré the illustrator; Baldine Saint Girons here provides the coda-essay, “Lake in Scotland after a Storm.” Éduard Capet's “Doré, Sculptor” offers a valuable discussion of its subject, though one that seems absolutely unaware of British sculpture. Paul Lang here provides the coda with a fascinating discussion of Doré's bizarre, wonderful giant bronze vase. Six plates from Paradise Lost then precede Eric Zafran's “Doré in America” and Anna Markova's “Doré in Russia.” This massive catalogue closes with Valentine Robert's “Cinema and the Work of Doré,” an interview with Phillipe Druillet and appendices containing “A Short Biography,” “List of Works,” “Selected List of Illustrations by Gustave Doré,” “List of Exhibitions,” “Selected Bibliography,” and an index of names. Whew.

Where do we go next?

Despite the fact that Doré not only worked in England but directed much of his work at English (and American) audiences, the authors of the various essays, who concentrate on how Doré influenced others, show surprisingly little interest in obvious points of influence upon him.

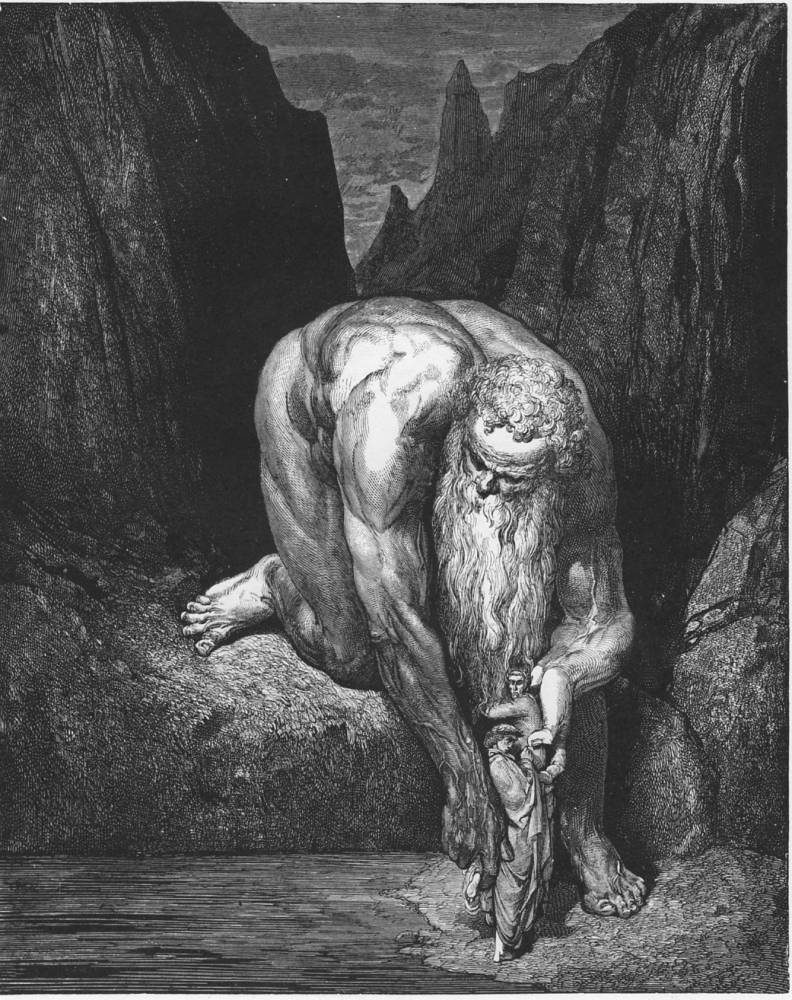

The Giant Antaeus [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

The Giant Antaeus, Doré's illustration of the Inferno's canto 31, seems obviously dependent upon William Blake's Nebuchadnezzar, Isaac Newton, or The Ancient of Days, while the composition of The House of Caiaphas has much in common with that of Holman Hunt's The Finding of the Saviour in the Temple (1860). Similarly, Doré's wonderful Scottish landscapes seem very close to works by Alfred Breanski, David Farquharson, and other Scottish artists as well as those by the German-American Albert Bierstadt. Looking at a work in a different key, one wonders to what extent the trees at the left of The Art Institute of Chicago's Scottish Landscape (1873) — no. 195 in the exhibition — derive from trees in landscapes by Turner or Lear.

Doré, as this fine exhibition demonstrates, had so many different styles and worked in so many different genres and mediums that one wants to see what he took and what he rejected from contemporary art outside France. Certainly, all these similarities, like the question of Doré's relation to British illustration, deserves another exhibition or two. Philippe Kaenel and his fellow contributors have whetted our appetites with this wonderful show, and we want more.

Bibliography

Kaenel, Philippe. Gustave Doré, Master of Imagination. Paris: Musée d'Orsay; Ottawa: National Gallery of Canada, 2014.

Last modified 19 June 2014