The Meeting of Jacob and Rachel, by William Dyce, R.A. (1806-1864). Oil painting on canvas. 1850. 14 x 18 inches (36 x 46 cm). Private collection. Image courtesy of Sotheby's, London. [Click on the images on this page to enlarge them.]

Dyce exhibited the initial version of The Meeting of Jacob and Rachel at the Royal Academy in 1850, no. 92, accompanied by these lines in the exhibition catalogue: "And Jacob kissed Rachel and lifted up his voice and wept." In 1857 it was exhibited again at the Manchester Art Treasures exhibition, no. 134, lent by William Bowery. The painting is based on a story from the book of Genesis, Chapter XXIX, 9-12, in which Jacob sees his cousin Rachel for the first time as she stands by a well: "While he was still talking with them, Rachel came with her father's sheep, for she was a shepherd. When Jacob saw Rachel, daughter of his uncle Laban, and Laban's sheep, he went over and rolled the stone away from the mouth of the well and watered his uncle's sheep. Then Jacob kissed Rachel and began to weep aloud. He had told Rachel that he was a relative of her father and a son of Rebekah. So she ran and told her father."

The episode portrayed in Dyce's picture is immediately before Jacob kisses the modest Rachel; in this interpretation, he has obviously fallen in love with her at first sight. Christopher Newall, in his comment for Sotheby's in 2009, has given a fuller explanation of the scene:

The urgency of his emotion, and her demure acceptance of his love, is poignantly conveyed by the way in which he leans forward to look directly into her face, resting his hand on the nape of her neck and pressing hers to his chest, while she stands before him without recoiling or resisting him, only looking downwards in a gesture of modest acceptance of his adoring attention. Rachel's father, Laban, was to trick Jacob into working for him for fourteen years without payment, on the understanding that he would eventually be able to marry Rachel, and then insisted that Jacob should first marry Rachel's elder sister, Leah, before eventually allowing Rachel to be his wife. The subject therefore alludes to the abiding and patient love that Jacob was to show to Rachel.

There were at least four versions of this painting by Dyce, differing in size and with minor variations, although the poses of the figures remain the same in all versions. The original version was the one sold at Sotheby's, London, on 15 July 2009, lot 5, and is now in a private collection. Its most distinctive feature, differing from all other versions, is in it the young Jacob wears a beard. William Holman Hunt made a copy of this painting in 1850 at Dyce's request, presumably to satisfy the desire of a collector unable to buy the work being exhibited at the Royal Academy. One of the best of the replicas is the large version now at the Leicester Museum and Art Gallery, shown below.

Another version of the work, also oil on canvas. c.1850-53. 27 3/4 x 35 7/8 inches (70.5 x 91 cm). Collection of the Leicester Museum and Art Gallery. Accession no. L.F32.1937.0.0. Image courtesy of the Leicester Museum and Art Gallery under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial licence (CC BY-NC).

The slightly smaller version of Jacob and Rachel in the Kunsthalle, Hamburg is likely the version he exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1853, no. 140. It differs from other versions in small ways.

On the left is the version painted in 1853. 22 7/8 x 22 7/8 inches (58 x 58 cm). Collection of Hamburger Kunsthalle, inventory no. HK-1840. Photo: Elke Walford. Image courtesy of Hamburger Kunsthalle, reproduced in an earlier (2016) version of this web-page by George P. Landow. It is Figure 14 in Lionel Gossman’s "Unwilling Moderns" (see bibliography).

This version shows the figures full-length, not three-quarter length, and it has an arched top like in Dyce's preliminary drawing of this subject of c.1850 in Aberdeen Museums and Art Gallery. Here the sheep in the background are standing rather than lying down. The water bottle or wine flask that Jacob normally has fastened to his waist is lost and the cloak he is generally seen wearing on his back has been replaced by a sheepskin. There are no palm trees in the right background of this version. Staley has pointed out that in the Hamburg version the two figures appear anachronistically to be standing before a Scottish loch and not a biblical landscape (273). Another version, again showing the figures at three-quarter length, was painted in 1857. It was presented to St Lawrence's, Knodishall, in Suffolk in 1948 by W. J. Burningham, but in the 1980s the church sold it and it is now untraced.

The Influence of the Nazarenes and Pre-Raphaelitism

Dyce's painting, although executed after his initial encounters with the early work of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, shows the continued influence of the Nazarenes on his work. Lionel Lambourne has explained Dyce's affinity with them — "their Christian primitivism appealed to his Scottish pietism" (45). Staley too has commented on "how strongly Nazarene are Dyce's clear outlines, precise drawing, and hard bright colours" (273). The subject of Jacob and Rachel had been treated earlier by several members of the Nazarenes, including in a drawing by Schnorr von Carolsfeld now in the Kupferstich-Kabinett, Dresden. For his part, Keith Andrews sees Dyce's painting as being "related to [Joseph von] Führich's treatment of the same subject (1836) in general feeling," but notes that "it is, if anything, more intense in expression and colour" (82). Andrews goes on to add, however, that the work was indeed influenced by Pre-Raphaelitism: "By this time the art of the Pre-Raphaelites, whom Dyce was among the first recognize, is reflected back onto his own work. The 'minutiae' of the ground and the stonewall come close to Pre-Raphaelite 'truth.' Yet they do not obtrude, and the emotive moment is, as in Führich's picture, beautifully expressed. Having concentrated on the two main figures only, and discarded the chorus of surrounding persons, which rather conventionalized Führich's version, Dyce achieves a dramatic intensity which the vivid colours only enhance" (131).

Contemporary Reviews of the Picture

When the initial version of this painting was shown at the Royal Academy in 1850 it was extensively and favourably reviewed. The critic for The Art Journal was gratly impressed: "The figures are half-length. Rachel rests the left hand on the side of the well, the other, Jacob presses to his bosom as he bends towards her. In determining the character of the heads of these figures it would appear that the result is a deduction of sedulous study; everything approaching to effeminacy in the one, and mere prettiness in the other, has been carefully avoided. The drawing is vigorous, and the style of costume original. Rachel wears a blue drapery, covering the shoulders and bust, and leaving the arms nude; and Jacob is partially clad in goat-skin, which, crossing the body, is confined at the waist by a girdle. We cannot too highly praise this work; it is a most masterly production, in all respects honourable to the British School of Art" (167).

The Athenaeum's reviewer was equally enthusiastic, feeling that the picture incorporated all the best qualities of works of the quattrocento while leaving out their deficiencies: "The charms of the modest maiden – the 'beautiful and well favoured' – are seen to have made their immediate impression on the youthful Jacob. With all the fervour of impassioned love he pleads his suit. Mr. Dyce has rendered all the points of the story ... in a species of art-description which has availed itself of some of the more popular modes of expression of the earlier masters of the fifteenth century, omitting the dryness and accidental peculiarity of their time. The distinctness and methodical arrangement which the fresco style demands are made by him subservient to the expression of a very beautiful episode in a spirit and quality of refinement well befitting it" (509).

The Builder too felt this to be one of the finest paintings in the entire exhibition, and not a mere imitation of an Old Master picture: Dyce, he says, in rendering the "often repeated" episode, "leaves an impression equal to the effect of anything in the collection. Influenced by his love for the severe, he has not extended it to that heterogeneal defiance of nature observable in younger disciples of the school: he has produced a perfect picture, and the manner of treatment, far from being suggestive of pedantry, is beautifully in unison with the subject, and implies an exalted sympathy with the feelings of former masters, not a servile attempt to imitate. The cool silvery grey key of the work is in excellent keeping with the conception: as a whole, it is a performance of which any country might be proud at any time" (217-18). The Spectator review was somewhat less glowing, calling it: "rather a realist version of the subject, but very pleasing" (426).

When the version now at Hamburg was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1853 it was again reviewed but far less extensively. The critic of The Art Journal merely contrasted it with the earlier version: "In this picture, which is small, the impersonations are presented at full length. The subject, it may be remembered, has already been exhibited by the painter; but larger; and if our memory serves us, the figures were half-length. These are, we think, circumstanced as in the larger work" (143) The reviewer for The Athenaeum admired both the draughtsmanship and colour shown in the painting: "The Meeting of Jacob and Rachel (140) by Mr. Dyce is a charming picture. The animation of Jacob and the shrinking modesty of Rachel are finely expressed, – the drawing is faultless, and the colouring pure and harmonious" (566). The Illustrated London News admired both the composition and its technical qualities, calling it "a small picture, cleverly conceived, and carefully and tastefully executed. Jacob rushes forward with ardour to greet Rachel, who standing motionless, her eyes downcast, receives him but coldly. The limbs are well studied; flesh well rounded, and delicately coloured" (349). The The Spectator's art critic did not discuss the picture in any detail, since it was merely a version of his earlier submission: "Mr. Dyce exhibits a full-length, but smaller, repetition of The Meeting of Jacob and Rachel, sent in 1850. The sentiment is chaste and lovely in a high degree, the execution that of a thorough artist; but the colour will not be fully sympathized with unless by the devotee of a system. As the picture is a repetition, we quit it with these otherwise inadequate comments" (446).

Writing of Dyce's entire career in The Art Journal in 1860, James Dafforne felt this work had been influenced by Titian: "In 1850 he exhibited Jacob and Rachel… a masterly production, full of fine feeling, and without the least approach to vapid sentimentalism. The draperies are well studied as to truth of costume, and are rich in colour; the work throughout, in treatment and execution, may not inappropriately be termed Titianesque" (296).

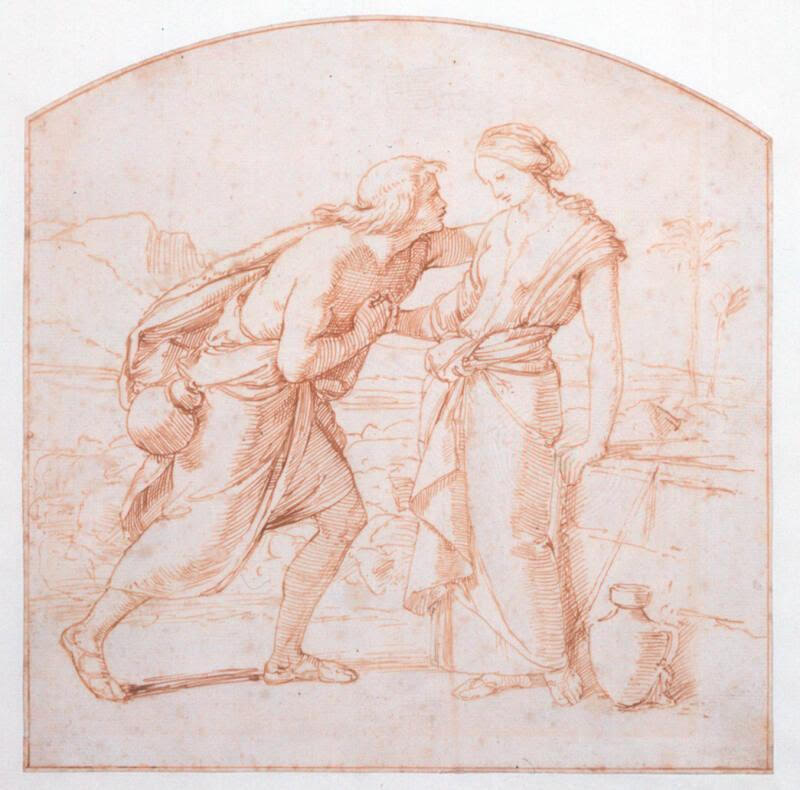

Study for The Meeting of Jacob and Rachel. c.1850. Pen and ink on paper. 8 1/4 x 8 1/4 inches (21.1 x 21 cm), arched top. Collection of the Aberdeen Art Gallery and Museum, object no. ABDAG003231. Image reproduced here for the purpose of non-commercial research, courtesy of the Aberdeen Art Gallery and Museums.

Of interest also is the early pen-and-ink study for the composition, shown on the right, in the collection of Aberdeen Art Gallery and Museums. This shows the figures full-length. There is also a wood engraving of the initial version of the picture, engraved by Butterworth and Heath, which appeared in the The Art Journal in 1860 (p. 295). The Dalziel Brothers too made a wood engraving in the 1860s after the first version of the painting— this was intended for the Dalziel Bible Gallery, but for some reason was not included when the book was published 1881. It was first reproduced in Art Pictures from the Old Testament, published by the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge in 1894 (p. 33).

Bibliography

5: William Dyce, R.A., H.R.S.A.. Sotheby's. Web. 16 December 2024.

Andrews, Keith. The Nazarenes. A Brotherhood of German Painters in Rome. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1964.

"The Arts. The Royal Academy." The Spectator XXIII (4 May 1850): 426-27.

Dafforne, James. "British Artists: Their Style and Character. No. LI. - William Dyce." The Art Journal New Series VI (1860): 293-96.

"The Eighty-Fifth Exhibition of the Royal Academy." The Art Journal New Series V (1 June 1853): 141-52.

"Exhibition of the Royal Academy." The Illustrated London News XXII (9 May 1853): 348-50.

"Fine Arts. Royal Academy." The Athenaeum No. 1176 (11 May 1850): 508-09.

"Fine Arts. Royal Academy." The Athenaeum No. 1332 (7 May 1850): 566-67.

"Fine Arts. The Royal Academy Exhibition." The Spectator XXVI (7 May 1853): 446-47.

Gossman, Lionel. "Unwilling Moderns: The Nazarene Painters of the Nineteenth Century." Full text on this website.

Hunt, William Holman. Pre-Raphaelitism and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. London: MacMillan & Co. Ltd., 1905, Vol. I, 206-07.

Jakob begegnet Rahel, 1853. Hamburger Kunsthalle. Web. 16 December 2024.

Lambourne, Lionel. Victorian Painting. London and New York: Phaidon, 1999.

Melville, Jennifer. William Dyce and the Pre-Raphaelite Vision. Ed. Jennifer Melville. Aberdeen: Aberdeen City Council, 2006, cat. 35, 142-43.

Newall, Christopher. The Pre-Raphaelites. Stockholm: Nationalmuseum, 2009, cat. 24, 160.

_____. Victorian and Edwardian Art. London: Sotheby's (15 July 2009); lot 5.

Pointon, Marcia. William Dyce 1806-1864 – A Critical Biography. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1979. 119 & 196.

_____. "William Dyce as a Painter of Biblical Subjects." The Art Bulletin LVIII, No. 2 (June 1876): 265.

"The Royal Academy." The Art Journal XII (1 June 1850): 165-78.

"The Royal Academy Exhibition." The Builder VIII No. 379 (11 May 1850): 217-18.

Staley, Allen. The Pre-Raphaelite Landscape. Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1973. 21-22.

_____. Romantic Art in Britain. Paintings and Drawings 1760-1860. Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1968, cat. 190, 272-73.

Study for "The Meeting Jacob and Rachel." Aberdeen Archives, Gallery and Museum. Web. 16 December 2024.

Vaughan, William. German Romanticism and English Art. New Haven and London: Yales University Press, 1979. See pp. 195, 197, 200.

Created 22 September 2016.

Two more images, and commentary, added 16 December 2024