[The following essay about the Nazarenes comes from German Paintings of the 19th Century — the catalogue for the author’s pioneering exhibition which took place at three venues: The Yale University Art Gallery, The Cleveland Museum of Art, and The Art Institute of Chicago. The German government awarded my friend and colleague a medal for this show. — George P. Landow]

Of the many Germans who individually and in groups colonized Rome during the nineteenth century, certainly the Nazarenes (in particular Friedrich Overbeck, Franz Pforr and later, Peter Cornelius, and Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld did so with the greatest energy and dedication. Beginning as a group of sincere, if arrogant, refugees from the Vienna Academy, the original Nazarenes, or to use their own chosen name, the Brothers of St. Luke, set out for Rome in order to work in the piously primitive Christian spirit of old German and fifteenth-century Italian painting. After they arrived they settled in the abandoned cloister of San Isidoro and established their manner of communal life along traditional monastic lines. Embracing the city of Rome with an enthusiasm comparable to that which they had already begun to direct toward the Roman Church prior to their departure from Vienna, the Nazarenes remained for almost twenty years a permanent fixture in the artistic scene of their adopted home. Yet for all their permanence, the various Nazarenes remained steadfastly German, exaggerating their German manner of dress, while at the same time building in their minds and in their art the bridge between Christian “Italia and Germania” to which their lives and their art were dedicated. Italy, and Rome in particular, freed the Nazarenes to “be German” in a way they felt they could not be in the artistic confusion of their native country. Unlike Koch or Schick, the Nazarene painters saw themselves in one or another way as exiles from Germany and from an impious modern world in general. There was, however, no general agreement among them as to whether or not their exile was to be irrevocable. In most cases it was not. From his position in exile, Peter Cornelius both entertained and encouraged a succession of invitations to reform various academies back in Germany. First Dusseldorf, then Munich, then Berlin requested his services; and by 1840 either Cornelius himself or one of his fellow Nazarenes (Wilhelm Schadow, Schnorr, Philip Viet, Johann Anton Ramboux, Johann David Passavent, Joseph Führich, Edward von Steinle, and Joseph Wintergerst) had received responsible academic appointments in Germany. Only Overbeck lived out his life in Rome, but in doing so he provided a point of pilgrimage—almost a live monument—for later generations of both German and non-German artists.

Overbeck’s reputation and that of the Nazarenes in general had become increasingly international after 1830. This is quite remarkable when one examines the great variety of styles and ambitions which were eventually maintained by one or another member of the group. In the period prior to Pforr’s early death (1812) something like a Nazarene style had begun to develop as a complement to the bonds of close personal friendship which initially held the group together. If Pforr’s taste for fifteenth-century German panel painting and manuscript illumination ran a good deal deeper than Overbeck’s, and if Overbeck’s earliest paintings inevitably stress the Italian side of “Italia and Germania” with their references to Perugino, Francesco Francia, and early Raphael, a shared enthusiasm for graceful linear drawing and flat, bright, primary color, smoothed out for a time smaller differences of taste. As the Nazarene circle expanded, differing and much stronger points of taste expanded correspondingly. Cornelius and Schadow both figured in the great Nazarene fresco commissions for the Casa Bartholdy (Palazzo Zuccari) in 1815 and the Casino Massimo (1817-29 with much confusion and reassignment in between). Dürer, Signorelli, and the late works of Raphael were increasingly persistent influences on the styles of both artists. Their designs tended to be rather complicated and grandiose, while those of Overbeck and other artists like Viet were comparatively feminine in their self-conscious refinement. Increasingly, the burden of stylistic coherence in the Nazarene group rested on the ancient technique of fresco and upon certain conventions which the technique itself forced. Every artist had had to master fresco technique in order to work on the great group projects; but real stylistic coherence was already severely threatened in the Casa Bartholdy project and, by the time of the Casino Massimo, it was almost nonexistent, conclusively so after Cornelius’s departure in 1821. Almost inconceivably the major burden of finishing a large portion of work at the Casino Massimo originally assigned to Cornelius fell to Koch, who, though a friend of the Nazarenes, had never participated directly either in their projects or in their circle. Furthermore, Koch had not himself had any experience in fresco painting, or for that matter in large scale figure painting of any sort. However, for reasons not entirely clear, he was drawn into the work of the Casino Massimo and provided several elaborate scenes from Dante. Koch’s paintings with their wierdly scaled rhythms and their leathery figural relief, while impressive, demonstrated very effectively the passing of anything resembling a Nazarene style. His contribution was archaic even by Nazarene standards. . . .

For all of its enormous internal variations in matters of style, the painting of the Nazarenes achieved a considerable degree of influence both in Rome and in Germany itself. The technique of fresco and the selection of at least generically similar models from the art of the early Renaissance produced a characteristically hard and dominantly two-dimensional kind of painting—linear in its essence and rejecting all virtuosity (and interest) in the handling of paint. Subject matter was at first primarily Christian, although later in the works of Cornelius and Schnorr historical, mythological, and folkloric subjects came to the fore. As various members of the Nazarene group infiltrated academies in Germany, the basic values which had been held jointly began to exercise a deep and lasting effect. From roughly 1825 to 1850 Nazarenism provided what was really the only artistic common denominator between academies (and the art public) in various parts of Germany. In the hands of Cornelius, Nazarene values were made to serve the quasi-political, quasi-historical interests of German monarchy, through large, decorative commissions (many of which were never executed) granted him first by the Bavarian Royal House, later by the Prussian. In the hands of Schnorr they became truly popular through wide circulation of his illustrations of the Bible.

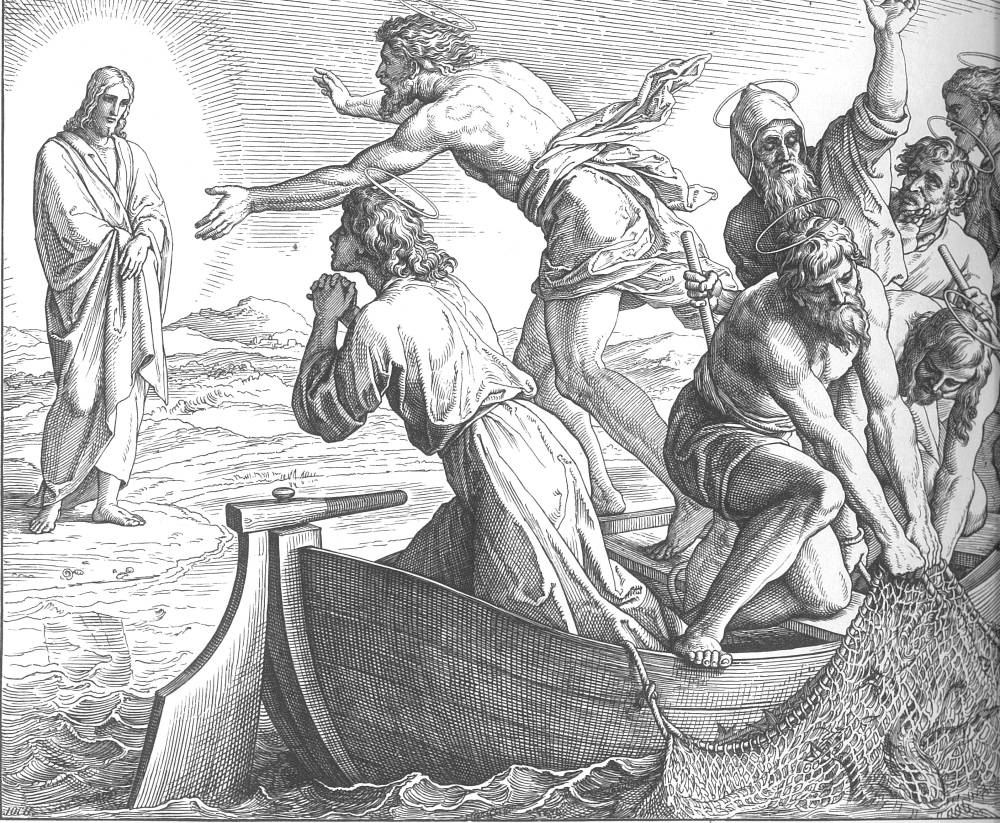

Two of Schnorr von Carolsfeld’s Bible illustrations. Left: Christ at the Sea of Galilee. Right: The Annunciation. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

It would, however, be a mistake to assume that Nazarenism, for all its influence, represented the preeminent factor in German painting at any historical point. German academies possessed a seemingly infinite capacity to assimilate, and in assimilating, to dissipate. Along with its Nazarene elements each academy sheltered others as well. Exactly what the others were and what they proposed as alternatives to Nazarenism differed according to the histories of particular academies. Düsseldorf, which operated under Wilhelm Schadow’s direction for twenty-three years (1825-48) is a perfect case in point. There an arch-Nazarene director headed a school which stressed, increasingly as the years passed, work from nature, becoming finally as much a landscape academy as one fostering Christian or other types of historical subjects. Clearly the fact that Schadow’s father had, during his own directorship of the Berlin Academy, stressed the importance of working from nature (to the lasting discontent of Goethe) laid a foundation for the eventually un-Nazarene breadth of Schadow’s tolerance. The very existence of such tolerance in what was potentially the most Nazarene of academies (as well as in Schadow’s own painting) demonstrates quite forcefully the relativity of Nazarene influence within Germany, whatever its apparent prominence.

From his permanent residence in Rome Overbeck may in the final analysis have been as influential as any of his fellow Nazarenes who had chosen to return to Germany. While his artistic efforts grew less impressive over the years, his position as an exile and as the ur-Nazarene continued to attract younger artists who visited Rome. [17-19]

Related material

Bibliography

Champa, Kermit S., and Kate H. Champa. German Paintings of the 19th Century. Exhibition catalogue. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970.

Created 19 June 2016