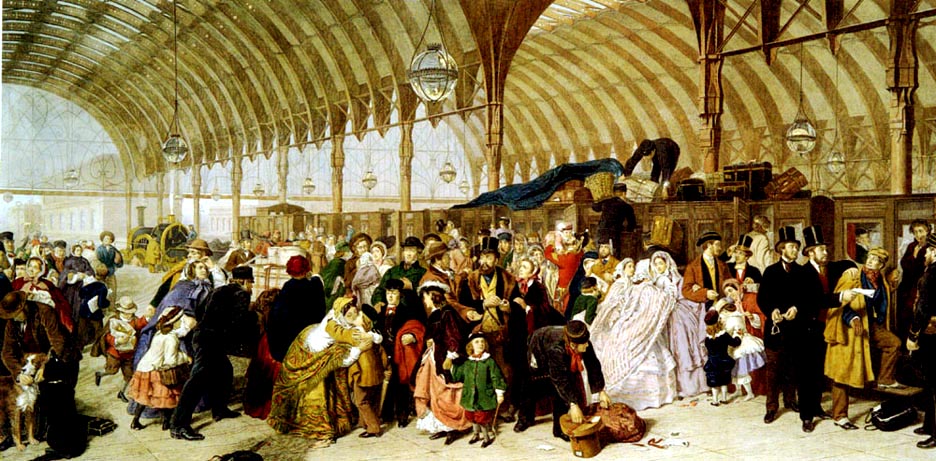

The General Post Office, One Minute to Six by George Hicks. 1860. Oil on canvas. Reproduced by kind permission of the Museum of London, which retains copyright.

Commentary by Catherine J. Golden, Professor of English, Skidmore College

George Elgar Hicks (1824-1914) made his reputation painting diverse London crowds in scenes from everyday life — at the bank in Dividend Day, Bank of England (1859), at the post in The General Post Office, One Minute to Six (1860), and at a fish market in Billingsgate Market (1870). The General Post Office, which now hangs in the Museum of London, reveals that by 1860, Victorians of different occupations and social classes depended on getting to the General Post Office before 6:00 PM closing time, even after the advent of the telegraph, to prepay and post death notices, urgent letters home, and missives of love. By 1861, one year after Hicks displayed his painting, patrons also depended upon their local post offices to deposit money in a Post Office savings bank. In 1869, the Post Office purchased the telegraph companies, and in 1882, telephone facilities became available through the Post Office, too, illustrating why the Victorians regularly depended upon their local post offices.

In his painting, Hicks guides us into the massive entryway of the General Post Office in St. Martin's-le-Grand, designed by Robert Smirke, the architect of the British Museum (image). There we find young and old, rich and poor, man and woman, thief and law enforcer, human and canine. Amid the ongoing bustle at one minute to closing are compelling characters — a whistling newsboy, a pickpocket at work, a frantic office boy carrying business post, and a kindly man leading a lost girl. Fittingly, all eyes look toward the postal window that outside the picture plane.

[Click on this and other thumbnails for larger images. Move (or close) the larger images to uncover this discussion of the painting.]

Three central parts compose Hicks's canvas. At the far left, a police officer catches a young pickpocket in the act of picking the pocket of a woman, who is totally unaware the thievery is about to take place. The boy’s intended victim — an unsuspecting genteel woman in pale lilac-gray dress and a pink bonnet — also seems not to notice a tall, bearded policemen, who intervenes to stop the crime mid-theft. The figure of the blue-uniformed policeman stands as an emblem of the law. The insignia "A29," visible on the policeman's collar, designates his division and exact number in a London police squad; this detail quite literally extends the arm of the law and illustrates how the Penny Post brought the innocent and unsuspecting into dangerous contact with criminal elements of society.

A section extending from the left to the middle of the canvas features a young girl, lost in the bustle of the crowd and on the brink of tears; a kindly gentleman in a red coat and black top hat man has come to her aid. The lost child is the first in a cluster of five figures that form a tableau of anxious Post Office patrons — all of them looking earnestly toward the Post Office window. For example, Hicks has painted the errand boy (behind the woman in the dark tartan shawl) with a fixed gaze and set jaw, suggestive of tension and urgency. Will he get the letters he carries, presumably from the business employing him, to the window on time? These figures evoke the bewilderment that Victorians experienced following the legislation of cheap postage as they rushed daily among chaotic, mixed crowds to make the last daily post.

A third story unfolds to the far right of the canvas. There we witness the rush of activity accompanying the daily distribution of newspapers. Men and boys clamor under the weight of bundles of newspapers, which await delivery.

Critics attacked Hicks’s painting. Frederick George Stephens dismissed the painting in The Athenaeum: “Indeed, but for its prominent position, we should pass it over in silence” (688). Some criticized the painting for offering a romanticized view of the rush to catch the last post; Fraser’s, for example, notes “the crowd is evidently a select crowd; and from its general cleanness and neatness might pass for a set of persons in good society performing the final scene in the charade of ‘Post-office’” (878). Other Victorian critics like W. Thornbury, writing in The May Exhibition: A Guide to the Pictures at the Royal Academy, at least recognized Hicks’s merits; as an artist, Thornbury notes, Hicks “seems now resolutely bent on Hogarthian scenes of London life’” but adds that if he rendered them “’less powerfully than our great satirist,’” he did so “certainly more genteely’” (qtd. in Bills 550).

Critics aside, crowds flocked to see the wildly popular painting on display in the West Gallery of the National Gallery (image) in Trafalgar Square. The crowds even caught the attention of Punch. According to a column in the June 16, 1860 issue, “the crush represented in MR. HICKS'S picture gives only a faint idea of the crowd around it. The glimpses which you catch of it, between hats, over shoulders, and under arms, increase the reality of the scene” (246).

Frith's The Railway Station [Click on thumbnail for larger image.]

For Hicks’s choice of subject matter, art historians today such as Mark Bills have placed Hicks’s work in the same category as William Powell Frith’s famous images of Victorian society. In The Railway Station (1862), for example, Frith depicts Paddington Station as a microcosm of Victorian society and crowds his canvas with people from all walks of life, including a criminal, a cabby, detectives, servants, a bride and groom, and members of his own family. Hicks’s similar assembly of characters of different social classes and occupations earned The General Post Office Bills’s praise for conveying “a striking statement about the pace of activity in the city, about the behaviour of the crowd, and the role of the centralized post and press system at the heart of a vast empire” (550). Through urgency and pathos of his subject, Hicks excelled in portraying how the Penny Post had become integral to the bustle of Victorian daily life.

References

Bills, Mark "The General Post Office: One Minute to Six." Burlington Magazine (September 2002): 550-56.

Golden, Catherine J. Posting It: The Victorian Revolution in Letter Writing. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2009.

“Jack Easel.” Punch (16 June 1860): 246.

Stephens, Frederick George. “Royal Academy.” Athenaeum (May 19, 1860): 688.

Last modified 12 June 2010