This paper was given as one of a series of talks at Leighton House Museum, London celebrating Frederic Leighton’s painting Clytie, bought by the museum in 2008 (http://www.rbkc.gov.uk/subsites/museums/leightonhousemuseum).

Victorian Clytie

The retelling, representing and revisioning of classical myth was not unique to the Victorian age: mythology themes had dominated the painted canvas from the Renaissance. There is, however, a marked difference in the treatment of these same myths by Victorian painters and artists of previous centuries. While the Renaissance produced many-figured canvases of passion and excitement, Victorian artists select more personal and intimate scenes of reflective individuals. Here moments from mythological narratives are chosen that favour individual and intimate scenes of lost love. And, of course, the poster girl for lost love is Clytie: the sea nymph who falls in love with the sun god Apollo; whose love is unrequited, and who pines away to be transformed into a sunflower on death. Ovid’s Metamorphoses, a Latin text used virtually as a mythological handbook by artists since the Renaissance, tells her moving story:

She wasted away, deranged by her experience of love. Impatient of the nymphs, night and day, under the open sky, she sat dishevelled, bareheaded, on the bare earth. Without food or water, fasting, for nine days, she lived only on dew and tears, and did not stir from the ground. She only gazed at the god’s aspect as he passed, and turned her face towards him. They say that her limbs clung to the soil, and that her ghastly pallor changed part of her appearance to that of a bloodless plant: but part was reddened, and a flower hid her face. She turns, always, towards the sun; though her roots hold her fast, her love remains unaltered. [Ovid, Metamorphoses IV:256-273, trans. A S Kline]

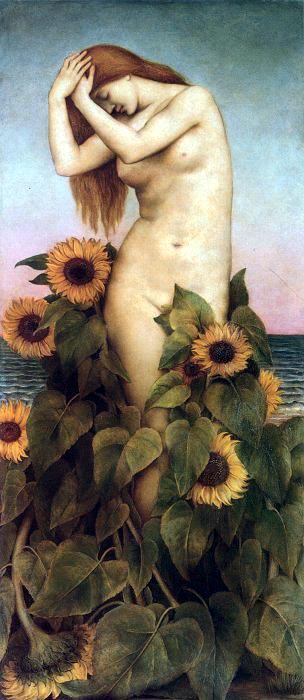

Leighton's second Clytie, of 1895-96.

This essay will look at Frederic Leighton’s depiction of the Clytie myth, and examine how much his painting is a product of its age.Leighton painted two pictures on the same theme. The first, Clytie (1890-2: image available at the Fizwilliam Museum site) is a landscape, where the nymph is only a small figure in the right hand corner of the canvas, shown keeling before a statue of Apollo (identified by the lyre that he holds). The focus of the picture is its dramatic skyscape rather than this tiny figure. A gorgeous sunset colors the sky and its ever moving clouds, while Clytie kneels in worship, clinging onto the last rays of the sun before night falls. Leighton’s second version of the myth (1895-6 takes the small kneeling figure in the landscape, and expands her to form the subject of a whole picture. His last painting, it remained unfinished at Leighton’s death.

The artist explains his picture as follows:

I have shown the goddess in adoration before the setting sun, whose last rays are permeating her whole being. With upraised arms, she is entreating her beloved one not to forsake her. A flood of golden light saturates the scene, and to carry out my intention, I have changed my model’s hair from black to auburn. To the right is a small altar, upon which is an offering of fruit, and upon a pillar beyond I shall show the feet of a statue of Apollo. [quoted in Jones, Frederic Leighton, 240]

Leighton exaggerates Clytie’s importance, upgrading her from a nymph to a goddess, and then paints her obsessive desire for the sun god Apollo. Clytie’s association with the sunflower makes her an unsurprising choice for a Victorian artist.

The sunflower as late-Victorian decorative motif. Left: William de Morgan's Sunflower tile. Middle two: Two examples of the sunflower in brickwork. Right: Book binding reputed to have been designed by D. G. Rossetti. . [Click on these images to enlarge them and to obtain additional information.]

After Oscar Wilde praised the sunflower, along with the lily, as “the two most perfect models of design”, it became an emblem of the Aesthetic Movement. In Edward Linley Sambourne’s caricature for Punch in 1881, Oscar Wilde is himself shown turning into a sunflower and American cartoons produced during Wilde’s tour of the States the following year invariably play on the same theme. The sunflower was also used as a motif in the decorative arts of the 1880s and ’90s with William Morris’ sunflower ceramic tile design soon imitated by the Minton pottery factory. The sunflower was also used to decorate domestic objects from letter racks and ink wells to brass bedsteads and wrought-ironwork railings.

Clytie by George Frederic Watts in terracotta, bronze, and oil on panel [Click on these images to enlarge them and to obtain additional information.]

Evelyn de Morgan’s Clytie

The myth of Clytie was represented by other Victorian artists as well as Leighton. Evelyn de Morgan’s Clytie (1886) combines the design motif of the sunflower with the myth of the grieving nymph. Unlike Leighton’s Clytie who welcomes the sun with outstretched arms, de Morgan’s figure bends her head away rather than towards the sun. This painting focuses more on the pathos of Clytie’s situation than her desperate love. More dramatically George Frederick Watts’ canvas and bronze bust (1865-9) illustrate the moment of metamorphosis. Emerging from flower leaves, his Clytie strains her body to follow the sun, awkwardly and painfully twisting her head over her right shoulder. While de Morgan’s painting is sorrowful and Watts’ is dramatic, Leighton’s Clytie is by far the most emotional of the three reworkings of the same myth. In Leighton’s Clytie the woman’s whole body is raised upwards towards the sun that she loves; she opens her arms to welcome his embrace. Indeed, the language that the artist used in describing his painting – “ have shown the goddess in adoration before the setting sun, whose last rays are permeating her whole being” – is intensely physical; the language of sexual possession. What is particularly interesting here is that the sexuality referenced is female.

Apollo and Daphne

A long classical tradition identifies the sun god, Apollo, as a desirer of women. His loves were not celebrated like Jupiter’s, however, as they all ended badly. The myths of Clymene, Coronis, Dryope and Daphne all define the god as sexual aggressor. And his pursuit of Daphne, his first love, and her metamorphosis into a laurel tree, in particular, is a popular pictorial subject where countless Daphnes flee from their pursuing Apollos. The most famous of these is Bernini’s Apollo and Daphne (1622-5: Galleria Borghese), in which the amorous Apollo catches up with the object of his desire, only for her to be metamorphosed into a laurel tree under his touch.

Such a dynamic figure group emphasises both the sexually aggressive passion of Apollo and the equally strong terror of Daphne. Depicting both characters in flight and showing the transformation of Daphne’s hair and arms was one of the main ways of representing this myth. This mode of representation was popular in illustrated editions of Ovid and is also evident in Antonio Pollaiuolo’s Apollo and Daphne (c. 1480; National Gallery) in which the ill-fated pair is similarly shown in flight. In this version, both characters are dressed as contemporary Florentines set against an unmistakeably Florentine background. While the outcome of this story is clear from the full foliage sprouting out of her arms and the tree trunk forming out of her left leg, the characters seem to be embracing in a swift-paced amorous dance, without the signs of terror or aggression present in Bernini’s version.

Pollaiuolo’s contemporised version gives us insight into how such a sexually charged aggression and metamorphosis of the human form could be made palatable to Renaissance courtly audiences. It also might help us to understand why this particular Ovidian myth was the major exception to the rule of decorum that the dignity and integrity of the human body should be respected and not shown undergoing a metamorphosis.

The other main way of representing Daphne and Apollo was as a static pair, with Daphne rooted firmly to a spot, shown as a tree trunk with a human head. Such versions were common in moralised editions of Ovid, on cassoni and early painted mythologies. These versions appropriately show the allegorical consequences of lust, but also, for new wives looking at cassoni, exhort the viewer to give into her husband’s desires to consummate the marriage and to produce offspring. Sexual aggression is thus made palatable by the hoped for outcome of reproduction.

The subject of Apollo and Daphne, continued to be a mainstay of art historical tradition from the fifteenth to eighteenth centuries, but thereafter waned in popularity and by the Victorian period it is rarely depicted. One of the few paintings of the subject is ’s Daphne (1895: image available on artmagick.com) which, like many canvases of the period, concentrates on one figure, and excludes Apollo to focus on an apprehensive Daphne at the moment of transformation.

Clytie in the Renaissance

More often, Victorian artists look to Clytie, a relatively obscure episode in representations of Apollo myths until now. In fact few paintings of Clytie exist from the Renaissance period. We must first turn to the various illustrated versions of Ovid’s Metamorphoses to get a sense of how the role of this character was understood during this period. We can then examine the few existing Renaissance paintings and compare them to Victorian versions and to Leighton’s in particular.

In the illustrated versions of the Metamorphoses from the fifteenth to the seventeenth centuries, Clytie is presented as a secondary character and indeed as an attribute to the more popular story of Leucothea, sometimes referred to as her sister, though not in Ovid. Clytie’s story occurs in the larger tale of Apollo’s love for Leucothea (IV, 169-270). Having been struck with an arrow from Cupid on Venus’ orders in revenge for having revealed her love affair with Ares to her husband Hephaestos, Apollo fell in love with Leucothea. In order to fulfil his desires he approached Leucothea in her house disguised as her mother and having won her affections, commenced a love affair that was only interrupted when the jealous Clytie told King Orchanus of his daughter’s liasons with the sun god. In anger, the king had his daughter buried alive and Apollo’s tears for her transformed her body into a frankincense tree.

An interesting iconographic tradition relating to this episode was born because of a mis-translation in the fourteenth-century Italian prose paraphrase by Giovanni di Bonsignori, a text which served as the basis for the later illustrated editions of the Metamorphoses and which itself had picked up the error from Giovanni di Virgilio’s earlier allegorical interpretations of Ovid’s text (Elisa Saviani; see Iconos for all these translations). In Ovid’s poem, Apollo sent his rays of sun to revive Leucothea, but Bonsignori wrote that the sun god put down his rays and tried to dig up her body. This became the standard way of representing the story as illustrated in the following three editions of the Metamorphoses: J. Spreng's Metamorphoses Illustratae, illustrated by Virgil Solis (1563), and its precursors, Simeoni’s, Vita et Metamorfoseo d'Ovidio (1559) and with the exact same images, the Métamorphose Figurée (1557) All of these images are narrations with the figures of Apollo and Leucothea appearing in the foreground in an amorous pose indoors, with Leucothea half buried in the ground and Apollo trying to dig her up with a spade in the background.

Antonio Rusconi’s illustrations for Ludovico Dolce’s Trasformazioni (1553) continues this error, although the emphasis is no longer on the love-making couple, but on the end result of their affair. Rusconi’s illustration of this episode, commissioned before Dolce’s text was complete, contrasts with the text itself, which had the correct version of Ovid’s story. In this image Apollo digging with his spade and the half buried Leucothea take pride of place in the foreground. Rusconi also manages, however, to give almost equal prominence to the naked Clytie in the middle ground, lying desperately on the ground watching the sun in the sky, pining away her days until she is eventually transformed into a sunflower. This illustration is important for connecting the two parts of this larger story, making Clytie an essential part of the whole episode. It also gave artists a new emphasis, offering them a chance to depict the suffering, rejected Clytie.

Rusconi also represented Leucothea and Clytie in an image that further ties them together as part of the same story and the wider events narrated in Metamorphoses IV. While Clytie is almost fully transformed into a bunch of sunflowers, Leucothea has already been fully transformed into a frankincense bush and on the right in the background, rain is being transformed into the Curetes, an episode which follows on chronologically from this one (Metamorphoses IV, 414). These two images by Rusconi are important then, firstly for including Clytie prominently in Leucothea’s story, secondly for giving equal weight to both of these loves of Apollo in their ultimate transformations, and thirdly for introducing the theme of the suffering Clytie, which would become the mainstay of our later Victorian representations.

It was only when Grotius removed all reference to the persistent error of Apollo digging up Leucothea in his edition from 1590-91, that we see this motif disappear (Elisa Saviani, Iconos). Grotius also included Clytie in his illustration of the Leucothea story, although she seems again to be only incidental to the main event in the foreground. We see her walk in on the two lovers in bed through a doorway in the background In George Sandys’ translation of Ovid’s Metamorphoses (1632), we have a summary of the whole of Book IV in one image. In the foreground, Apollo, disguised as an old woman, approaches Leucothea, identified by the frankincense tree behind her, and grabs her hand. Clytie does appear in this part of the image, but only as a distant figure on the horizon, crouched on the ground looking up at the sun. Such an image of the desolate Clytie is also what Peter Paul Rubens chose to present in his small panel painting, Clytie Grieving (1636-38). This painting captures the pain and suffering of this wretched young woman as her body seems to blend into the landscape. Without the sunflower, we can identify her through her longing gaze at the clearly visible rays of the sun. This isolated female longingly staring at the sun points clearly in the direction that will be followed by Victorian artists.

Charles de la Fosse’s Clytie Transformed into a Sunflower

Charles de la Fosse’s version of this myth avoids such pain and anguish, however, and presents Clytie as a part of an idyllic setting, with nymphs and young men in amorous embraces, only identifying Clytie by her sunflowers (1688). Apollo rides his chariot in the distance and Clytie seems to be lost in her thoughts about her beloved, holding onto sun-warmed garments, oblivious to what is going on around her. In the following century this idyllic setting for Clytie’s story is also taken up by Francis Boucher in his design for a tapestry of Clytie (c1750; Minneapolis Institute of Arts), which reveals her inner thoughts and portrays her wishfully thinking of an amorous encounter with Apollo. Reality occurs in the foreground, where Clytie daydreams by a riverside, full of sunflowers, while her fantasy occurs in the clouds, where she cuddles up close to the seated Apollo. Pulling the viewer into her fantasy, Boucher seems to make light of the story and no sense of the pathos present in Rubens or later Victorian artists occurs. In addition, while Apollo is desired by Clytie in Ovid’s story and he rejects her emphatically, Boucher seems – even while representing a female fantasy – to reinterpret the myth from the male point of view, representing Clytie daydreaming fully naked on the ground and with a happy countenance, turning her into the desired object of the male viewer, someone who, unlike Apollo, might accept the longing desire and love of Clytie.

Female desire

The Victorians favour a myth where the sun god is desired object rather than desiring subject. This is no coincidence as female desire had become a familiar subject, widely explored by artists and writers in nineteenth-century Britain. In Christina Rossetti’s narrative poem “Goblin Market” (1862), two sisters, Lizzie and Laura, are lured by sumptuous fruits, the traditional Biblical symbol of temptation. Laura cannot resist the fruits offered her by the goblins, and she buys them with a lock of her hair:

Then sucked their fruit globes fair or red:

Sweeter than honey from the rock,

Stronger than man-rejoicing wine,

Clearer than water flowed that juice;

She never tasted such before,

How should it cloy with length of use?

She sucked and sucked and sucked the more

Fruits which that unknown orchard bore,

She sucked until her lips were sore. [complete text]

Such an eroticized description suggests that the forbidden fruit refers to female sexuality. In the poem, Laura becomes ill after eating the fruit and pines away almost to death, but she is ultimately saved by her sister Lizzie. There is no such happy ending for Mariana, the heroine of Tennyson’s lyric poem (1830; text), who waits in vain for her lover to return. Tennyson’s poem was inspired by the character of Mariana in Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure. Rejected by her fiancé, Angelo, after her dowry was lost in a shipwreck, Mariana leads a lonely existence in a moated grange waiting for Angelo’s return. John Everett Millais chose lines from Tennyson’s poem to accompany his painting Mariana (1851) as catalogue quotation at exhibition in the Royal Academy of Arts:

She only said, 'My life is dreary,

He cometh not,' she said;

She said, 'I am aweary, aweary,

I would that I were dead!'

Left: John Everett Millais's Mariana

Right: John William Waterhouse's Mariana in the South

In the painting Mariana has been working at embroidery and pauses to stretch her back. Her languorous pose illustrates the boredom and longing of unrequited love. Scattered autumn leaves reflect how the season’s change, but her constancy and abandonment remain static. Tennyson reworked the poem with “Mariana in the South” (1833), used by John William Waterhouse as an inspiration for his painting of the subject (1897) Like Leighton’s Clytie, Mariana’s long hair falls over her back. As the only exposed part of the female body in all social classes, hair comes to take on a sexual meaning where its loosening signifies a lack of restraint. Millais’ Mariana, Waterhouse’s Mariana and Leighton’s Clytie all throw their heads backwards: the pose eroticizes the female body, and also signals sexual longing.

Tennyson continues to explore erotic yearning in “Fatima” (1833), a dramatic monologue portraying the frustration of a woman’s unrequited love. The first stanza describes the all-consuming passion of her desire.

O Love, Love, Love! O withering might!

O sun, that from thy noonday height

Shudderest when I strain my sight,

Throbbing thro' all thy heat and light,

Lo, falling from my constant mind,

Lo, parch'd and wither'd, deaf and blind,

I whirl like leaves in roaring wind.

Using Shakespeare in “Mariana” and the Arabian Nights in “Fatima”, Tennyson also looks to classical myth to source his desiring women. For example, “Oenone” (1829) refers to the myth of the mountain nymph who was the lover of the Trojan prince, Paris, before he abandoned her for Helen. In Tennyson’s poem the lonely nymph laments her faithless lover:

My eyes are full of tears, my heart of love,

My heart is breaking, and my eyes are dim,

And I am all aweary of my life

Edward Burne-Jones also appropriates classical myth for his representation of a desiring woman in Phyllis and Demophoon (1870:). On his way back from fighting at Troy, the Athenian prince, Demophoon, stops in Thrace where he meets and falls in love with the princess, Phyllis. He agrees to marry her, departs for Athens to settle his affairs and promises to return in six months time. When he fails to keep his promise, a distraught Phyllis hangs herself, and is turned into an almond tree. On his eventual return, Demophoon remorsefully embraces the tree, which blooms on his touch. Burne-Jones’ painting shows Phyllis emerging from the blossoming tree to hold tight onto Demophoon, who looks as if he cannot wait to run away again.

Victorian Women

So why are the Victorians so interested in female desire? An answer is usually sought in social history. The Victorian period saw a marked change in the position of women: female issues were at the forefront of the public agenda, and women gradually gained more rights and freedoms as the century progressed. The 1857 Matrimonial Causes Act reformed the law on divorce, moving litigation from the jurisdiction of the ecclesiastical courts, to the civil courts thus widening the availability of divorce. The year 1867 witnessed the formation of the National Society of Women’s Suffrage, and, by the end of the century, suffragettes often made the headiness with a phase of militancy. In 1870 the Married Women’s Property Act allowed a wife to retain her own property and earnings after marriage, whereas previously all a woman’s money and investments were automatically the property of her husband. Girton College in Cambridge, Britain’s first residential college for women was established in 1869 at the University of Cambridge, with Lady Margaret Hall at Oxford following in 1878.

Girton College, Cambridge designed by Alfred Waterhouse

By the beginning of the twentieth century, women had gained greater access to education, joined the work force in greater numbers, were marrying later (or not at all) and having fewer children. The stereotype of the passive wife and mother was being slowly undermined. But such a challenge to traditional gender stereotypes became a cause of social anxiety, and journalists, politicians, welfare reformers, and medical practitioners all hotly debated the ‘Woman Question’.

The Victorian era was also a period that witnessed the medicalization of human behaviour, and, women’s illness, in particular, connected mind and gendered body. When gynaecology emerged as medical speciality by the mid century, female anatomy was associated with mental health. Diagnoses of nymphomania, especially, increased. Diagnosis seemed very much hit and miss, and in some cases girls who read French novels, non-married women accused of flirtatious behaviour, or married women who were more interested in sex than their husbands, were labelled nymphomaniacs. It was the norm for women to be perceived as naturally less sexually desirous than men, and thus nymphomania became an umbrella term under which to explain all transgressions of female modesty. Doctors became protectors of morality, judging what was deemed appropriate behaviour and what was mental illness, with extreme cures including the removal of the ovaries or clitoris. Sexually deviant women were grouped together, and nymphomaniacs and prostitutes were frequently connected. As with nymphomania, the expectation of active and spontaneous male sexual activity, and a passive and responsive female partner, was challenged in the form of prostitution. The number of prostitutes in Victorian Britain remains uncertain (80,000 in London alone by some counts), but the notion of prostitution as a social and sexual challenge occupied the public forum through publications, from pornographers, social campaigners and doctors alike.

Misinformation surrounding sexually transmitted diseases singled out prostitutes as harbouring syphilis, and legislation in the form of the Contagious Diseases Acts of 1864 and 1869 targeted prostitutes for forced physical examination, to test for venereal disease. These laws enforced the irrational fear of women as the exclusive carriers of syphilis, and a danger to the male population. Cultural expressions of such a fear can be seen in representations of syphilitic death in female form, as strikingly illustrated in an etching by Belgian artist Félicien Rops, Mors Syphilitica (1892).

The classical world is again evoked through the use of the word “siren” as slang for prostitute. In Homer’s Odyssey, the Greek hero Odysseus encounters these dangerous creatures, who lure sailors with their beautiful voices to shipwreck on the rocky coast of their island. Although Homer says nothing of their appearance, the siren is described by later authors as being half-bird and half-human in form. She becomes gradually humanized until by the late antique period she had acquired a mermaid fish’s tail. In the Victorian period the mythological siren is popularized as a fully human femme fatale who seeks to lure unsuspecting men to their deaths.

Herbert Draper’s Ulysses and the Sirens

In Herbert Draper’s The Sea-Maiden (1894: Christies) fishermen excitedly hauling in a naked woman caught in their net, connects sirens, mermaids and the fatal danger of syphilis. The painting illustrates lines from Swinburne’s poem Chastelard, in which fishermen caught “a strange-haired woman with sad singing lips” and “having lain with her / Died soon”. Draper also paints sirens in Ulysses and the Sirens (1909)) in which a Homeric scene is transformed into a feast of female flesh. Three girlish nudes clamber up the side of the boat, while the hero strains forwards from his bonds, and the crew grit their teeth in their determination to keep rowing. Desirable and desiring women are once again juxtaposed with the men that they yearn to possess.

Eroticism and the sun god

Apollo, the object of Clytie’s affection is, of course, excluded from Leighton’s Clytie, a painting of solitary and unrequited passion. But the male body as love object is illustrated in another of Leighton’s (now damaged) painting depicting the sun god entitled Helios and Rhodes (1868-9: Tate Gallery). Helios, the ancient sun god (in later mythological traditions associated with Apollo), is embracing his lover Rhodes, a nymph who gave her name to the Greek island where the sun god was worshipped. The outstretched arms of Clytie clasp nothing but the air, Rhodes holds her lover in an encompassing embrace. Once again, a head thrown back and long, loose hair suggests erotic longing and here the woman’s arched back is supported by male muscular arms.

A similar configuration of male and female is found in Herbert Draper’s Day and the Dawn Star (1906: http://www.artmagick.com) in which a winged male, “Day”: the sun glowing on his dark, muscular body, embraces the ‘Dawn Star’, a pale, languishing female. Once again arched back, long neck, flowing hair suggest sexual abandon. Draper’s Day and the Dawn Star was exhibited at the Royal Academy with an unaccredited catalogue quotation: “To faint in the light of the sun she loves / To faint in his light and to die”. The lines are from Tennyson’s ‘Maud’, and the whole stanza reads:

For a breeze of morning moves, And the planet of Love is on high, Beginning to faint in the light that she loves On a bed of daffodil sky. To faint in the light of the sun she loves, To faint in his light and to die.

The “she” and the implied he of the lines become clearer through Draper’s representation of them as figures. Following Tennyson, Draper has anthropomorphized them, taking the male “sun” and the female “breeze of morning”, and transforming them into “Day” and the “Dawn Star”. At the same time, something of the erotic charge of the Tennyson passage as a whole transfers itself, once the identification is complete, to Draper’s canvas. Again the female is constructed as the recipient of the irresistible desirability of the male, a desirability that is, once again, encapsulated by the sun.

Flaming June by Frederick Lord Leighton, P. R. A. (1830-1896). Museo de Arte de Ponce, Puerto Rico

Leighton explores the power of the sun in a number of his works. Daedalus and Icarus (c.1869: http://www.frederic-leighton.org) depicts the myth of Icarus, who flies with wings made of wax and feathers by his father, the inventor Daedalus. Here the youthful nude Icarus, stands triumphant in anticipation of flight, although the mood is tempered by the poignant realization that he is soon to fall into the Aegean sea when the wax that fastens his wings is melted by the sun. A more positive painting is The Daphnephoria (1876: Liverpool Museums) showing a procession of youths and a chorus of women and girls celebrating the ancient Greek festival to Apollo. The procession is headed by a young priest of Apollo or Daphnephoros (laurel bearer), dressed in a white and gold robe, wearing a laurel wreath and a golden crown, and holding a bronze laurel branch. He is preceded and followed by other young men, whose semi-nude bodies proclaim the association between male desirability and the sun god Apollo. Further connections, this time between the sun and a powerful eroticism, are found in what is probably Leighton’s best-known painting, Flaming June (1895). In stunning saffron drapery a woman sleeps in the exhausting heat of the sun, which sets golden in the sea behind her. The transparent revealing drapery eroticizes the figure, while her flushed cheeks and flowing hair hint at the sensual pleasure she takes from the sun’s heat caressing her body.

The visual appropriation of Ovid’s retelling of the Apollo, Clytie and Leucothea myth changes over the centuries shifting from a Renaissance emphasis on a love-lorn Apollo grieving for Leucothea to a Victorian focus on female love and the desirability of the male sun. Leighton’s Clytie, then, is very much a product of its age. The Wildean and Aesthetic associations with the sunflower popularised the plant and sparked the interest of painters in the unfortunate nymph. At the same time, her narrative has all the right ingredients to appeal to the Victorian imagination: a classical myth, the melancholy of lost love, and, the fascination of a desiring woman.

Bibliography

The production of Leighton’s Clytie paintings is discussed in Jones (1996), Newall, (1990) and the Ormonds (1975), while de Morgan’s version is analyzed in Smith (2002) and Watts’ sculpture is considered in Bills and Bryant (2008). For an examination of the classical-subject movement in Victorian painting, see Barrow (2007). Bullen (1989) focuses on the meaning of solar mythology in the Victorian imagination. For a concentration on the representation of gender in classicizing imagery, see Kestner (1989), who links the changing social position of women with the representation of mythological fantasies. Relatedly, Dijkstra (1986) makes explicit connections between female mental illness and painted nymphs and maenads. Nymphomania and its relationship with medical and social discourse is the subject of Groneman (2001) with a particular focus on the nineteenth century found in Groneman (1994). Nead (1988) offers an overview of the roles occupied by women in Victorian painting, while the topic of female hair as sexual symbol is explored in Ofek (2009). A number of publications discuss Victorian sexuality and the changing roles of women in the period; among the most recent are Attwood (2010) and Gleadle (2001). For an examination of Tennysonian paintings, see Cheshire (2009) and an interesting undergraduate essay on the women of Tennyson’s poetry is found at a Cambridge University site. Different interpretations of Rossetti’s “Goblin Market” are included in Kooistra (1999).

For the Renaissance reception of Ovid’s myths, Bull (2005) is essential reading, while Reid (1993) is an excellent starting point for any investigation into classical myth in the visual arts. Two excellent online resources exist. The first, The Ovid Collection (www.lib.virginia.edu) provides access to the earliest printed editions of the Metamorphoses and its illustrated and moralised versions from the fifteenth through to the seventeenth centuries. The second, Iconos (www.iconos.it), more extensive in coverage and scope, is a vast resource for anyone interested in the visual and textual history of classical myth. It provides links to images and texts of such myths from classical, medieval and early modern sources and has extensive commentary on the images. This site is in Italian, however, but is nonetheless useful for its breath of coverage and can be easily navigated even by those without Italian.

Allen, Christoper. “Ovid in Art” in The Cambridge Companion to Ovid. Ed. Philip Hardie. Cambridge University Press: 2002, pp. 336-366.

Attwood, Nina. The Prostitute’s Body: Rewriting Prostitution in Victorian Britain. London: Pickering & Chatto, 2010.

Barrow, Rosemary. Creating Continuity with the Traditions of High Art: The Use of Classical Art and Literature by Victorian Painters 1860-1912. Lewiston NY: The Edwin Mellen Press, 2007.

Bills, Mark and Bryant, Barbara. G. F. Watts: Victorian Visionary. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008.

Bull, Malcolm. The Mirror of the Gods: Classical Mythology in Renaissance Art. London: Allen Lane, 2005.

Cheshire, Jim, ed., Tennyson Transformed: Alfred Lord Tennyson and Visual Culture. London: Lund Humphries, 2009.

Dijkstra, Bram. Idols of Perversity: Fantasies of Feminine Evil in Fin-de-Siècle Culture. Oxford: OUP, 1986.

Gleadle, Kathryn. British Women in the Nineteenth Century. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2001.

Groneman, Carol. “Nymphomania: The Historical Construction of Female Sexuality.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 19. 2 (1994): 337-367.

Groneman, Carol. Nymphomania: A History. London: W. W. Norton & Company, 2001.

Iconos: Viaggio interattivo nelle Metamorfosi di Ovidio. Università di Roma “La Spaienza.” Web. 30 October 2012.

Jones, Stephen et al, eds. Frederic Leighton. London: Royal Academy of Arts, 1996.

Kestner, Joseph. Mythology and Misogyny: The Social Discourse of Nineteenth-Century British Classical-Subject Painting. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1989.

Kooistra, Lorraine Janzen, ed. The Culture of Christina Rossetti: Female Poetics and Victorian Contexts. Athens OH: Ohio University Press, 1999.

Nead, Lynda. Myths of Sexuality: Representations of Women in Victorian Britain. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell, 1988.

Newall, Christopher. The Art of Lord Leighton. London: Phaidon Press Ltd. 1993.

Ofek, Galia. Representations of Hair in Victorian Literature and Culture. Farnham: Ashgate, 2009.

Ormond, Leonee and Richard. Lord Leighton. New Haven,:Yale University Press: 1975.

Reid, Jane Davidson. The Oxford Guide to Classical Mythology in the Arts, 1300-1990s. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press

Smith, Elise Lawton. Evelyn Pickering De Morgan and the Allegorical Body. Madison, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 2002.

Last modified 30 October 2012