he great engineers and industrial architects of the late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth centuries were esteemed not only as public benefactors, but also as true artists whose works enhanced the landscape. The mines and foundries, as well as the canals, bridges, aqueducts, and the tunnels which provided access to them, were more often than not situated in settings of conspicuous natural beauty.'The iron industry had not yet lost its picturesque character,' wrote Francis D. Klingender. 'Still surrounded by romantic scenery, the great ironworks, with their smouldering lime kilns and coke ovens, blazing furnaces and noisy forges, had a special attraction for eighteenth-century admirers of the sublime.'

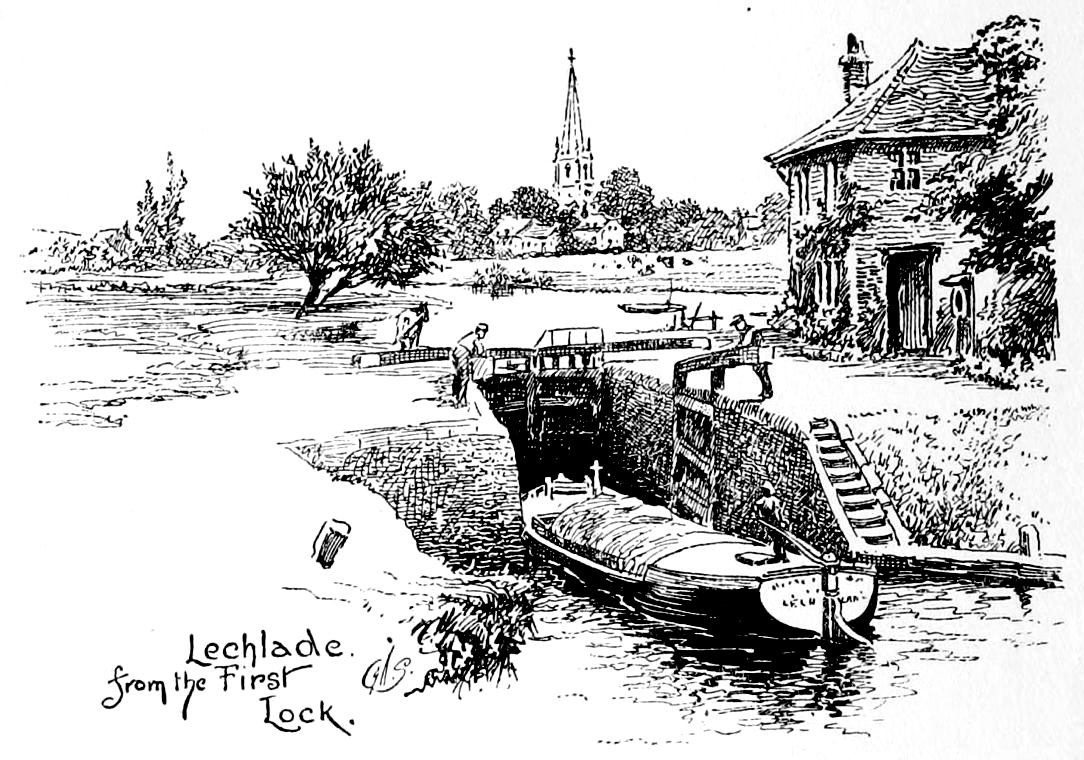

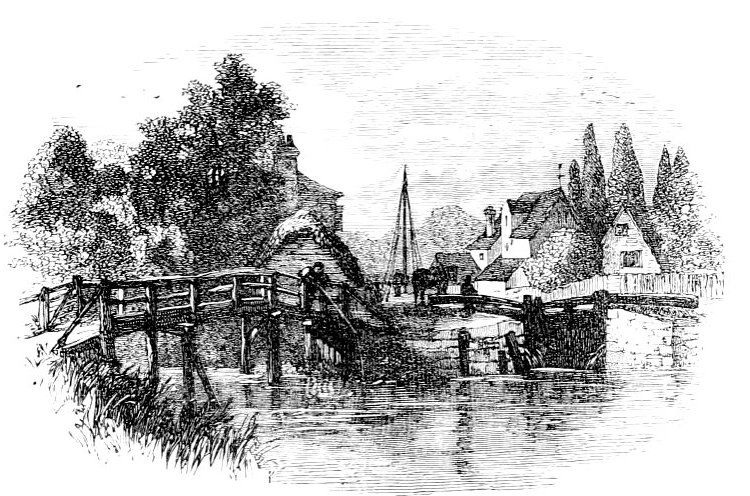

Canals in Victorian art. Left to right: (a) Lechlade from the First Lock by G. Ayton Symington. (b) Osney Lock near Oxford by E. W. Cooke. (c) Streatley Mill by Mortimer Menpes [Click on these images for larger pictures..]

A notable example was the vast industrial complex at Coalbrookdale on the Severn, near the site of the first iron bridge, erected in 1779 after Thomas Farnolls Pritchard's design. Among the artists who painted views of Goalbrookdale were George Robertson, de Loutherbourg, Rooker, Farington, John Sell Cotman, Paul Sandby Munn, and J. M. W. Turner. The treatment of such scenes parallels successive phases in the technique of landscape painting. For example, the topographical backdrop against which eighteenth-century draughtsmen projected their meticulously accurate drawings of machinery gave way to the 'picturesque' style adopted by their more poetically inclined followers. A number of masterpieces illustrates the artistic appeal of each new manifestation of Britain's inventive genius.

Joseph Wright, An Iron Forge. 1772. Oil paint on canvas, 1213 x 1320 mm. Collection: Tate Britain T06670. Purchased with assistance from the National Heritage Memorial Fund, the Art Fund and the Friends of the Tate Gallery 1992. Click on image to enlarge it.

In the 1770s Joseph Wright of Derby was painting his mannerist oils of the glowing interiors of forges and smithies. J. S. Cotman's tour of western England and Wales in 1802 produced two of his finest watercolors, 'Bedlam Furnace' (Coll. Sir Edmund Bacon) and 'Chirk Aqueduct' (Victoria & Albert Museum). Another generation onwards, the railway inspired works as challengingly original as Turner's 'Rain, Steam, and Speed' (1844, National Gallery) and David Cox's 'The Night Train' (1849, City of Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery).

Rain, Steam, and Speed by J. M. W. Turner

As a symbol of industrial progress, however, the factory town offered artists none of the romantic adjuncts of the mechanical marvels which had preceded its appearance. The initial optimism born of mastery over productive processes gave way to an awareness that the resulting economy had replaced hereditary ways of life with a wholly new and alien social environment. Artists tended to turn their backs on this spectacle as being incompatible with received ideals of high art. In Klingender's words: 'The alliance that had grown up in the late eighteenth century between science and art had a common foundation of humanism. When political economy abandoned the humanist standpoint for the defence of property the link between science and art was broken.' [450]

Bibliography

Johnson, E. D. H. “Victorian Artists and the Victorian Milieu” in The Victorian City: Images and Realities. Ed. H. J. Dyson and Michael Wolff. 2 vols. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1973. Pp. 449-74.

Last modified 3 August 2018