In 1852 he wrote to his father from Italy: "There is the strong instinct in me, which I cannot analyse, to draw and describe the things I love - not for reputation, nor for the good of others, nor for my own advantage, but a sort of instinct like that for eating and drinking." [20] — Christopher Newall

Ruskin is so frequently assumed to be a super "eye," a draftsman of high but somewhat anaesthetic mechanical excellence, a dispassionate observer, that it is proper to point out that the kinds of visualization with which he was preoccupied could not have evolved without imaginative effort and would not have been possible in the absence of powerful emotional impulses. [54] — Conal Shields

These last few years have certainly seen John Ruskin, the Pre-Raphaelites, their associates, and followers in the limelight. Take, for example, the major Pre-Raphaelite show at the Tate, which travelled to Washington, D.C., where I was fortunate to see it. And now we have this wonderful exhibition at the National Gallery of Ottawa of Ruskin's drawings (which will travel to Edinburgh). Reflecting upon these two major exhibitions, one finds they have significantly different tones: Magnificent as the Pre-Raphaelite show undoubtedly was, its organizers presented it in, well, somewhat timid terms, almost apologetically. In sharp contrast, Christopher Newall and his contributors — especially Conal Shields — present Ruskin to us, no hems and haws, as a great artist. And he is.

With the exception of Paul H. Walton, students of Ruskin have usually considered his drawings and watercolors, when they have considered them at all, not so much as the works of an artist but rather as those of a writer. In other words, they approached them chiefly as a means of understanding his life and writings. Such approaches make perfect sense, since, as Newall explains, “the sketchbooks and sheets that have come down to us provide an extraordinarily vivid notation on his experiences and the development of his patterns of thought. . . . and also give documentary information about his great writing projects” (19). His drawings did in fact provide what we would today term an image-base for his writings, and he made careful drawings of Venice, Fribourg, Rouen, and Abbeyville (quite a few of which appear in the exhibition) “because he knew that carefully made drawings of buildings or the wider topography would offer a level of recall equal to or beyond what might be instilled in a written account. On other occasions, he produced drawings of a diagrammatic character in which the exact profile of a carved moulding or sculpted patterning of a frieze or capital, or the precise formation of rock strata or shape of petals or stems in plants, or whatever else it be, were recorded on the basis of measurement and meticulous observation” (19).

Two stages in Ruskin's development as an artist — left to right: (a) Roslin Chapel (1838; cat 1). (b) Study of Thistle at Crossmount (1847; cat 71). The image at left © Ruskin Foundation; the one at right comes from the Library Edition. [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

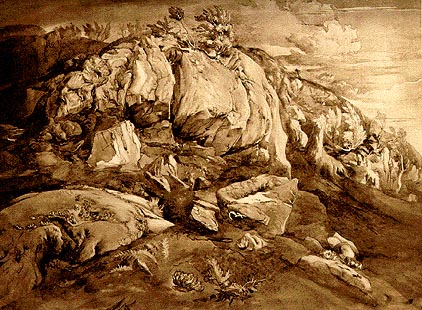

Newall's catalogue entries do an especially fine job relating Ruskin's mental states to individual works. For example, the one for the 1860s watercolor Lucerne reminds us that “Ruskin was a neurotic man given to extremes of ecstatic emotion and bleak despair. This pattern of bipolarity can be read in his drawings, which are on occasion exhilarating and joyous and on others marked by ominous forebodings” (178). Whereas Lucerne “speaks of his simple pleasure in being in a place where he felt secure, the experience of which reassured him that his work was worthwhile” (178), other works, such as the brilliant Crossmount, Perthshire; Study of Crag, Tree and Thistle (1847), presents us with what Newall describes as “rock formations that are strangely marked, with swelling protuberances and cracks and creases that bear analogy to human anatomy” (71).

Left: Mer de Glace, Chamonix (1838; cat 95). (b) The Walls of Lucerne (1847; cat. 30). Both Ruskin Library, Lancaster University. © Ruskin Foundation. [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

One of the great virtues of John Ruskin Artist and Observer appears in the skillful way that it explains the biographical and literary valences of each image without losing sight of its status as a work of art, something to be experienced on its own account. Following extremely helpful essays by Newall, Shields, Christopher Baker (on Ruskin and Scotland), and Ian Jeffrey (on Ruskin and daguerreotypes), the catalogue divides into seven categories, obviously none mutually exclusive: architectural detail and ornament, buildings, towns and topography, geology and foregrounds, mountains and skies, nature studies, and figures. The essays and individual entries show Ruskin's development from a student producing the work of a gentleman amateur, often to gain the approval of his parents, to a researcher recording both wide vistas and precise details for possible later use in his writings, and after that to an artist capable of both broader generalizations and records of intense moments of perception. Writing of Mer de Glace, Chamonix, France (1860), Newall explains that however Ruskin continued to draw and redraw both large scenes and the details of nature, his fundamental approach changed from that of mere student to something more personal than any attempt at simple objective recording of what he saw. These kinds of drawings are no longer geographical records but essays “in the shapes, textures and colours that characterize the Alpine environment in summer. In this sense, it marks a shift in artistic purpose on Ruskin's part from scrupulous and selfless observation of an actual physical setting to something more subjective and aimed to achieve aesthetic satisfaction” (300). Some of the late work, such as his View from the Palazzo Bembo to the Palazzo Grimani, Venice (1870), shows that “Ruskin was in tune with a broader evolution of taste.” John William Inchbold “had pioneered a way of representing cities and their wider settings as entire topographies with all their architectural elements melded into in organic whole,” and in his drawings of Venice in the 1870s, Ruskin, following an artist who had once followed him, “became more concerned with ambience and atmosphere than the itemization of particular buildings . . . [and] his method of painting in watercolour and draftsmanship in pencil and chalk adapted extraordinarily to the evocation of places by qualities of texture and colour” (57).

Left to right: (a) A Vineyard Walk at Lucca (cat. 58; see Newall's analysis of this work by clicking on the image). (b) Ruskin using body color: Piazza Santa Maria del Pianto, Rome (cat 39.).The image at left © Ruskin Foundation; the one at right comes from the Library Edition.

One of Newall's most important points involves the fundamental difference between Ruskin and contemporary professional artists. Most obviously perhaps, he used white body color when contemporary watercolorists considered that an outrage, a violation of the essential nature of their art. But Ruskin was willing to do anything regardless of convention if it captured what he saw and wanted to record. Ruskin always considered himself a beginning student, a view of himself that both allowed him to ignore contemporary strictures about finishing drawings and return, over and over again, to the same places and try to see more than he had ever done before and then to capture it in line and color.

Certain artistic predispositions on Ruskin's part gave unity to his drawn compositions and allowed their elements to blend harmoniously and organically. Instinctively, he tended to mass forms from curved and interwoven lines, while the textures of his drawings depended on the constant variation of tone by the placing together of subtly differentiated points of colour and the avoidance of even surfaces of paint. . . . Ruskin had at his disposal a most fluent and instinctive way of drawing and one that allowed him to work quickly, when he wanted to, whether in pen, pencil or with the point of a fine brush. In addition, he sketched in chalk and painted in watercolour and gouache, and made prints in etching and drypoint. [22]

Newall admits that “although there may be a temptation to regard Ruskin's work as an artist as something akin to a compulsion, done for its own sake and simply because he felt the need to draw” (19) (a wonderfully complimentary description of any artist) many of his works in fact served very practical needs and requirements. Accepting Newall's implied challenge, I would say that, yes, many of Ruskin's very best works are the result of “something akin to compulsion” and none the worse for it, for as Newall points out, “it was his indifference to the tedious business of working up subjects so that they might be judged as works of art by the conventional standards of the day that made his drawings abstractly beautiful and always spontaneous” (22) and always intensely personal. Ruskin created his drawings first of all to see and remember, and many of his most important ones capture a precise moment of vision, which for him meant recording a moment of sight and insight, after which the act of drawing ceased, something his father and many of his contemporaries could not understand. Ruskin felt no need to fill up white spaces in his paper. If what he had seen and wished to remember appeared on the sheet, he would stop. Many times, realizing that he had not come close to capturing all that he wanted to do, he would — immediately, or some days, or some years later — he would try again.

In Modern Painters and The Stones of Venice Ruskin showed himself the master of turning description into narrative, thereby capturing the reader's attention as he builds up a scene with proto-cinematic panning across a scene and moving in and out of it as the occasion demands. His famed word-painting, in other words, takes the form of story-telling that precisely reconstructs (or re-imagines) the history of his observations and his understanding of them, which he permits us to share. Mastering the master, Shield's often-brilliant “Ruskin as Artist: Seeing and Feeling” traces the movements of Ruskin's pens and brushes to show us the story of how a particular brilliant work took form. Taking Crossmount, Perthshire; Study of Crag, Tree and Thistle, 1847, a fine “example of Ruskin's fluent draftsmanship,” Shields shows how

the succession of marks shows that the artist began by touching in the portion of rock at the top centre of the sheet and outlining the plants emerging from. it. As his hand moved down and sideways from these, pencil was exchanged for pen and then brush. After the application of washes of fluctuating intensity there were localized bouts of further activity with the pen, and a white watercolour-laden brush was brought on to define the brightest of the features. It is almost an account of Ruskin's technical evolution: he proceeded from boundary-demarcation, through textural play, to indices of substance and spatial position. Ruskin's appetite for differentiation is unmissable. No aspect of the rock-pile is quite the same as another. The drawing, nonetheless, manages to convey simultaneously a vast quantity of highly specific information and an impression of mass and weight. The sky, added toward the end of the process, patently rehearses the procedure of the principal components. [53]

Similarly, when discussing Southwest Porch of St. Wulfran's, Abbeville (cat. 4), he points out that “it seems at first sight brusquely assured. But careful examination reveals a tentativeness, an acceptance of the possibility of modification that goes to the heart of Ruskin's approach to art and, indeed, his reading of the world. Ruskin's dogmatism is constantly qualified and frequently dissolved” (54). Ruskin was virtually the only nineteenth-century critic of art or aesthetician who recognized, much less emphasized, the physical aspect of creating art. It's therefor especially interesting to learn from Shields that “Ruskin was stimulated by the tools and materials he employed: pencils of different hardness allowed a degree of tentativeness in exploration; the pen answered a need for extreme precision; brushes, finely tipped or bushy, promoted a taste for textural play and general variety” (56-57).

Like Shields, Newall proves himself a superb student of Ruskin and of his drawings because he helps us see more in them than most of us could ever hope to see by ourselves. His commentary upon Ruskin's drawings of cornice decoration for The Stones of Venice explains that “ it was Ruskin's insight that the apparently unconscious shaping of cornices and mouldings, as well as arch profiles and the shape of window apertures, and any other part of a building if found in its original condition, might give some clue as to the larger state of mind of the men who created them” (96), and both he and Shields follow Ruskin's lead and apply this insight to Ruskin's own work.

View of Amalfi reproduced from the Library Edition.

Wishing for the apparently impossible, I would have liked to have seen some of the Fogg's dreamlike Ruskin watercolors, such as the 1844 View of Amalfi, but then Harvard (supposedly) never allows its Ruskin holdings to travel. Wanting something more likely, I would have liked a little closer look at the relation of Ruskin's art to that of J. D. Harding, who had a very great influence upon his aesthetic theories. But it is impolite to ask for more when we have been given so much in this fine exhibition.

Bibliography

Newall, Christopher (with contributions by Christopher Baker, Conal Shields, and Ian Jeffrey). John Ruskin Artist and Observer. Ottawa: National Gallery of Canada; London Paul Holberton Publishing, 2014. Pp. 376. ISBN 978-0-88884-919-9 (Canada); ISBN 978-1-907372-57-5 (rest of the world).

Barringer, Tim, Jason Rosenfeld, and Alison Smith. Pre-Raphaelite: Victorian Art and Design. London: Tate Publishing, 2012.

Walton, Paul H. The Drawings of John Ruskin. Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 1972. [Review]

Last modified 19 February 2014