lizabeth Thompson (who became Lady Butler on marriage, in 1877) achieved popular acclaim in the mid-Victorian period as an artist who depicted military subjects. Her prowess overcame the prejudice of John Ruskin against women artists, and her skill and patriotic appeal were such that people flocked to see her work. In 1874, the Prince of Wales praised her painting, The Roll Call, at the Royal Academy Banquet, and it was subsequently purchased — ceded by the Manchester industrialist Charles Galloway who had commissioned it, and taken from the wall, to the disappointment of eager crowds — by the Queen for the Royal Collection (Meynell 1). Several years later, in 1879, she came within two votes (the closest of any woman artist of the age) to being elected to associateship with the Royal Academy: in the last of three ballots, she received 25 votes to Hubert Von Herkomer's 27 (Meynell 11). To come this close to breaking into the great (male) world of the Academy was truly remarkable at the time.

Self-portrait, 1869 [click on the image for more information].

Thompson was born on 3 November 1846 in Lausanne, Switzerland, and spent much of her early life in Italy. Her childhood education was unusual, in that she and her sister Alice (who would make her name as the writer Alice Meynell) were taught at home by their "cultured, good, patient" father (Butler 1). A man of means, with an interest in the arts, Thomas James Thompson encouraged her talents, and, after a good deal of European travelling with her family, she persuaded her parents to let her study art professionally in the 1860s, attending "the Female School of Art" in South Kensington for what she described herself in her autobiography as "the happiest period of my girlhood" (14). In her autobiography, she wrote with great enthusiasm about the life class, where the "oil master" was James Collinson, and also of another class that she attended in London for "the 'undraped' female model" (45). Later, in 1869, she studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Florence. Here, in another significant step towards her future, her family converted to Roman Catholicism. Her art training meanwhile gave the skills needed to draw figures in her later work as, to use Paul Usherwood's term, a "battle painter" ("Butler [née Thompson").

Most aspiring women artists confined themselves to flower-painting, or the depiction of children and pleasant domestic or rustic scenes. Thompson's own mother, Christiana, was an accomplished amateur landscape painter, at a time when landscapes were becoming popular. Indeed, Thompson herself was skilful as a watercolour landscapist (see Gormanston 41). But she aimed to distinguish herself in quite a different way:

How strange it seems that I should have been so impregnated, if I may use the word, with the warrior spirit in art, seeing that we had had no soldiers in either my father’s or mother’s family! My father had a deep admiration for the great captains of war, but my mother detested war, though respecting deeply the heroism of the soldier. Though she and I had much in common, yet, as regards the military idea, we were somewhat far asunder; my dear and devoted mother wished to see me lean towards other phases of art as well, especially the religious phase, and my Italian studies in days to come very much inclined me to sacred subjects. But as time went on circumstances conducted me to the genre militaire, and there I have remained, as regards my principal oil paintings, with few exceptions. My own reading of war — that mysteriously inevitable recurrence throughout the sorrowful history of our world — is that it calls forth the noblest and the basest impulses of human nature. The painter should be careful to keep himself at a distance, lest the ignoble and vile details under his eyes should blind him irretrievably to the noble things that rise beyond. To see the mountain tops we must not approach the base, where the foot-hills mask the summits. [46-47]

In her chosen area, the young painter was influenced by other war artists, notably the Frenchmen Jean-Louis Meissonier (1815–1891), whom Ruskin himself admired, and the much younger Edouard Detaille (1848-1912), who had studied with Meissonier and taken his realism to a new level of accuracy. There was also a precedent for her aspiration to take on a subject that was unconventional for a woman: again, a French artist, Rosa Bonheur (1822-1899), who painted animals, particularly scenes of horses, and was much admired in England: she had attracted a good deal of attention here on her second visit in 1857. Indeed, in 1875 Thompson learned from Effie Millais that her husband had compared her favourably with Bonheur — though she herself was rather put out by the comparison: "I may be equal to Rosa Bonheur in power," she exclaimed in her autobiography, "but how widely apart lie our courses!" (132).

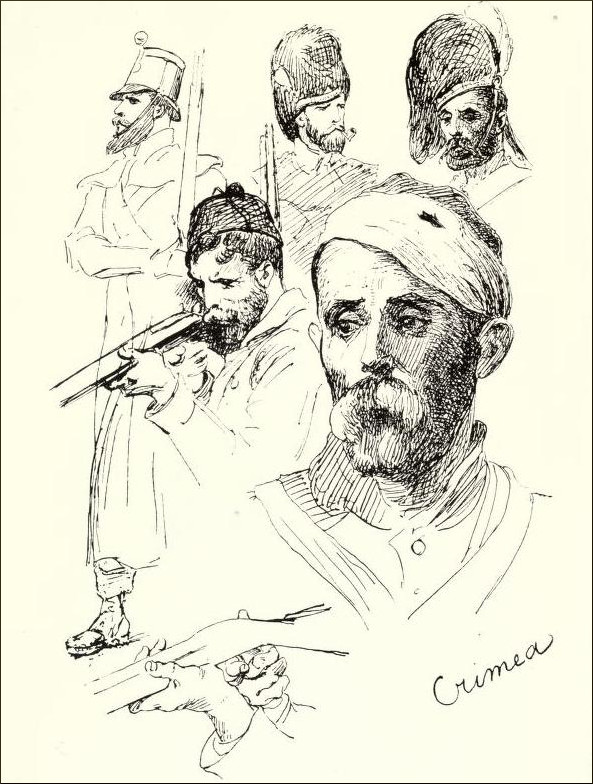

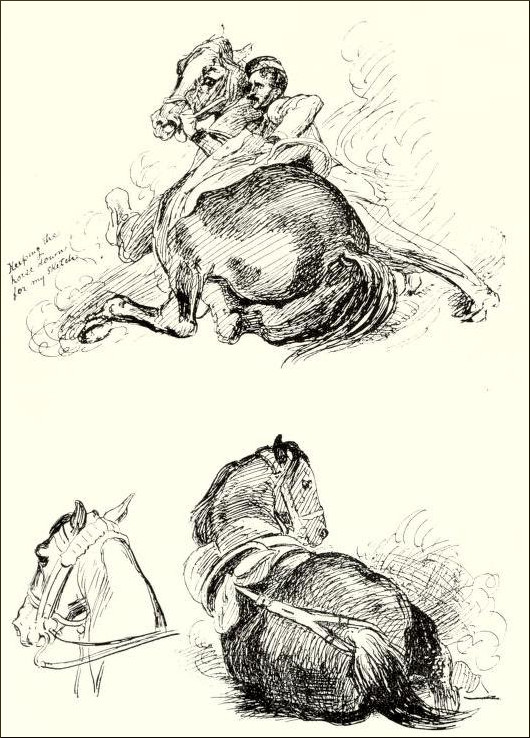

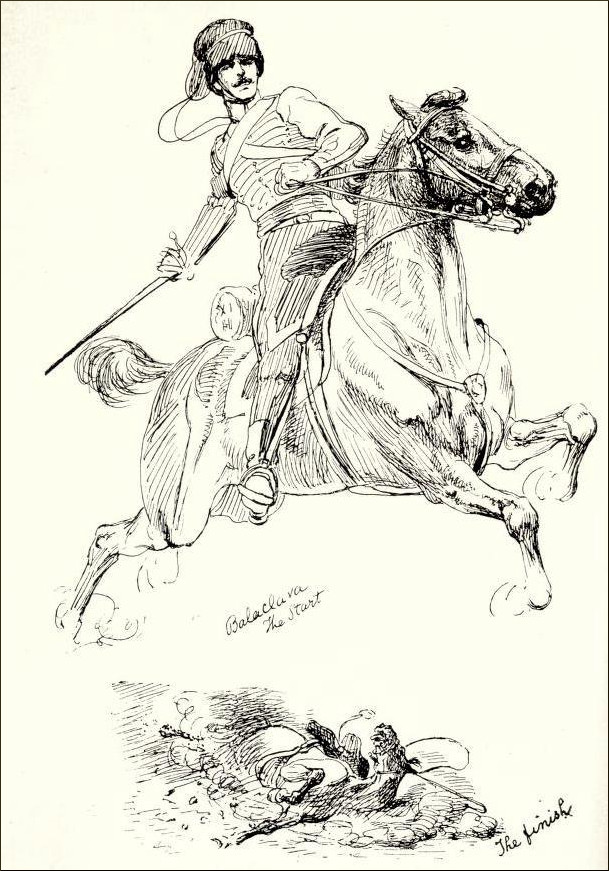

Sketches from the artist's autobiography. Left to right: (a) Crimean Ideas, p. 103. (b) Practising for "Quatre Bras", p. 130. (c) One of the Balaclava Six-Hundred, p.151.

By then, watching military manoeuvres in Southhampton in 1872 had made an impression on Thompson, although, it seems, this had confirmed rather than determined her own course: as early as January 1866, peeping for the very first time into the Life class in Kensington, she had been dazzled by "a splendid halberdier standing above the girls' heads and looking very uncomfortable. He had a steel headpiece and his hands were crossed upon the hilt of his sword in front, and his face, excessively picturesque with its grizzly moustache, was a tantalising sight for me!" (41). At any rate, battle scenes, often involving cavalry, with soldiers in their distinctive uniforms, exerted a strong pull on her. On a more practical level, the subject answered to her taste for dynamic scenes full of movement, and afforded her the opportunity to make her own mark in the art establishment. When her father had warned her, at the outset of her training, of the competition she would face, she had responded, "I will single myself out of it" (14). In this, she certainly succeeded.

The appeal such paintings made to patriotism, at a time of colonial expansion, was potent: the 1870s are generally considered to have been her heyday (e.g. see Chivers 98), and until marriage and motherhood claimed much of her time she was one of the most admired artists in the land. When Ruskin came to visit the family in 1868, she reports that the great man praised her "artillery water colour, ‘The Crest of the Hill’" and "knelt down before it where it hung low down and held a candle before it the better to see it, and exclaimed ‘Wonderful!’ two or three times, and said it had ‘immense power’" (52).

The success of The Roll Call in 1874 supported his judgment, and in his "Academy Notes," Ruskin would later say in print that he recognised in another work, The 28th Regiment at Quatre Bras of 1875, a Pre-Raphaelite fidelity in her attention to detail: he described this particular work as "the first fine Pre-Raphaelite picture of battle we have had," and felt bound to admit that he had been wrong to assume that "no woman could paint" (308).

Lieutenant Colonel W.F. Butler, CB. Taken in 1883 as Queen's ADC (about six years after marriage). Photogravure by Annan & Sons, Glasgow, from a photograph by Heath, Plymouth. Source: Butler, W.F., facing p. 250.

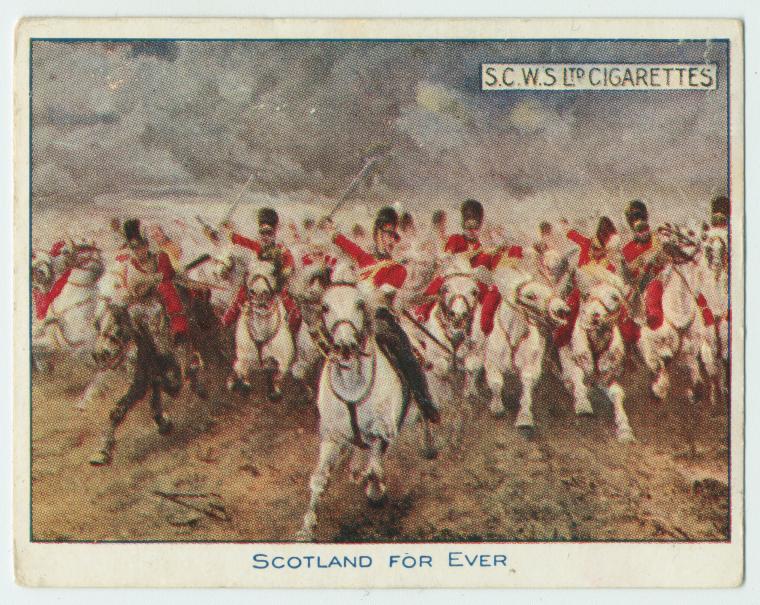

Looking back, Elizabeth Butler, as she was by this time, seemed to seek to vindicate herself by saying, "Thank God, I never painted for the glory of war, but to portray its pathos and heroism. If I had ever seen the corner of a real battlefield, I could never have painted another war picture" (qtd in her Times obituary, 17). By then, her army-officer husband, Sir William Francis Butler, who had been inoculated against jingoism and indeed imperialism by his Irish-Catholic background, had given her a somewhat different outlook on colonial warfare, and other war artists had emerged to capitalise unambiguously on the public mood for conquest and empire. Her work was still praised for its focus on the predicament of the ordinary ranks, which fitted with another current of contemporary thought — concern for the vulnerable and powerless. But after her great success with Scotland for Ever! in 1881, showing the charge of the Royal Scots Greys at the Battle of Waterloo, it never again seemed to touch the heights of her previous work.

Scotland Forever! was so popular that it appeared on cigarette cards, as jigsaw puzzles, etc. Image from the George Arant Collection, New York Public Library (See Bibliography).

Besides, marriage brought not only motherhood (the couple had six children after the first, who died at birth) but also, since she was now an army wife, more travels: "In the 1880s," explains Usherwood, William "was constantly on the move, serving in South Africa, Egypt, Canada, and the Sudan as well as spending time for personal reasons in Ireland and France" ("Elizabeth Thompson Butler: The Consequences of Marriage," 30). She wrote movingly about the lot of the army wife, often torn between her duties to her husband and children, and on her last visit to Egypt in 1891-92, at the end of which William was promoted to Brigadier-General, she poignantly expressed her regret at missing "The Private View at the far-away Royal Academy" (227). She did manage to continue painting after Scotland for Ever!, for example, exhibiting another work on the subject of Waterloo, "Dawn of Waterloo." The "Reveille" in the bivouac of the Scots Greys on the morning of the battle, 1815, at the Royal Academy in 1895. But the kind of celebrity that she had once enjoyed, now eluded her.

Gormanston Castle, Co. Meath, photographed by Kieran Campbell, originally posted on geograph.org.uk, and reproduced under the term sof the Creative Commons CC BY-SA 2.0 licence.

Usherwood is surely right to suggest in his essay on Thompson's marriage that, despite its advantages for her, her husband's career had simply taken precedence over hers. She outlived him, still painting in her old age, despite increasing frailty and deafness. In her daughter Eileen's autobiography she emerges as still feisty, still positive; but her reputation and perhaps even her powers as an artist had faded. Eileen had also married into an Irish Catholic family, an aristocratic one at that, and her widowed mother spent her last eleven years or so with her at Gormanston Castle, County Meath, where she passed away on 2 October 1933. She had almost completed her 86th year. Many newspapers, including the Times, carried obituaries of the woman artist who undoubtedly came nearer than any other to cutting a major figure in the Victorian art world.

Bibliography

Armstrong, Walter. "The Henry Tate Collection, V." The Art-Journal, Vol. 55 (1893): 287-301. HathiTrust, from a copy in the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Web. 25 November 2024.

Beckett, Ian F. W. "Butler, Sir William Francis (1838–1910), army officer and author." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Online ed. Web. 24 November 2024.

Butler, Elizabeth. An Autobiography. London: Constable, 1922. Internet Archive, from a copy in Robarts Library, University of Toronto. Web. 25 November 2024.

Butler, William Francis, Sir. An Autobiography. New York: Scribner's, 1911. Internet Archive, from a copy in New York Public Library. Web. 25 November 2024.

Chilvers, Ian. "Butler, Elizabeth (Lady Butler, née Thompson)." The Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists. 4th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009: 97-98.

"Dawn of Waterloo." The "Reveille" in the bivouac of the Scots Greys on the morning of the battle, 1815. National Army Museum. Web. 25 November 2024. https://collection.nam.ac.uk/detail.php?acc=2021-12-1-1-1

George Arents Collection, The New York Public Library. "Scotland For Ever." New York Public Library Digital Collections. Web. 28 November 2024. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e2-f35d-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

Gormanston, Eileen Butler Preston, Viscountess. A Little I Kept. New York: Sheed and Ward, 1953.

"Lady Butler" (Obituary). The Times. 4 October 1933: 17. Times Digital Archive (subscription needed).

Lambourne, Lionel. Victorian Painting. London and New York: Phaidon, 1999 (see pp. 198-99).

Meynell, Wilfrid. The Life and Work of Lady Butler. London: The Art-Journal, 1898. HathiTrust, from a copy in Princeton University. Web. 25 November 2024.

"The Roll Call." The Royal Collection Trust. Web. 25 November 2024. https://www.rct.uk/collection/405915/the-roll-call

Ruskin, John. "Academy Notes, 1875." Complete Works, edited by E.T. Cook and Alexander Wedderburn. Vol 14: 263-310. London: George Allen, 1904. Internet Archive, from a copy in the Getty Research Institute. Web. 25 November 2024.

Usherwood, Paul. "Butler [née Thompson], Elizabeth Southerden, Lady Butler (1846–1933), military painter." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Online ed. Web. 24 November 2024.

_____. “Elizabeth Thompson Butler: The Consequences of Marriage.” Woman’s Art Journal 9, no. 1 (1988): 30–34. https://doi.org/10.2307/1358360

Usherwood, Paul and Jenny Spencer-Smith. Lady Butler, Battle Artist, 1846-1933. Gloucester: Sutton and the National Army Museum, 1987.

Created 25 November 2024

Last modified 1 December 2024