Throughout Hunt's long and distinguished career, he clung to his original Pre-Raphaelite ideals.... What is remarkable is that his genius never diminished, and that the pictures he painted in old age are as vigorous and compelling as the works of his early maturity. [Amor 275]

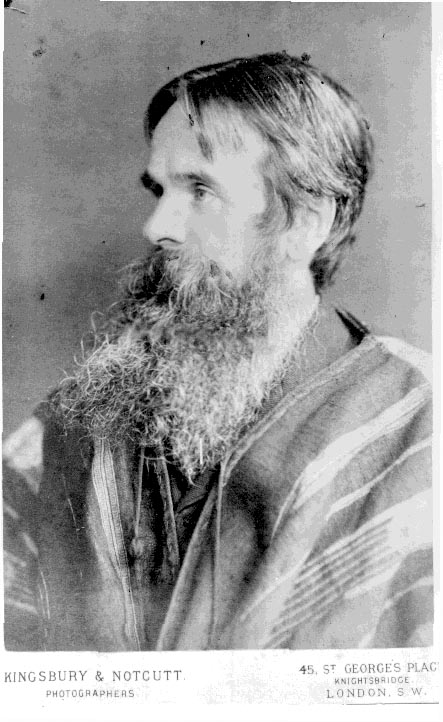

Hunt in c.1856, by Kingsbury & Notcutt, photographers. [Click to enlarge.]

William Holman Hunt (1827-1910) was a founding member of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, and the one who remained most consistently faithful to its aims. A true Londoner, he was the son of a warehouse manager, born above the warehouse off Cheapside, and baptised at St Giles, Cripplegate. At first, his father encouraged his artistic gifts, but only as a hobby. He wanted his son to follow in his footsteps, so when the boy made it clear that he wanted to be an artist, he took him out of school, intending to start him off as a messenger-boy at the warehouse. Hunt was only twelve, but he was enterprising enough to find a more congenial job — as a copying clerk for an estate agent, James Labram. Again, his gifts were spotted: Labram was impressed by his artwork, and introduced him to oil-painting. The youth now began to take his own artistic education in hand, by attending drawing classes at a mechanics' institute, and, briefly, studying at his own cost with a portrait-painter, Henry Rogers. At last, in 1844, having followed sound advice from the even younger John Everett Millais, Hunt entered the Royal Academy Schools as a probationer, and finally became a student there in 1845. Millais would become his lifelong friend.

The Light of the World, Keble College version (1851-53). [Click to enlarge.]

There were still years of struggle ahead, but a major turning-point for Hunt came in 1847 when he read the second volume of John Ruskin's Modern Painters and came upon his explanation of the way Tintoretto’s use of Biblical typology permeated painting which had realistic details with complex, integrated symbolism. This passage gave the young artist a solution to what he saw as the great artistic problem of the age: "Of all its readers none could have felt more strongly than myself that it was written for him" (Hunt 73). Hunt went to Millais and read him the passage, and both agreed later that this was the origin of Pre-Raphaelitism. Hunt's early attempts to combine realism with elaborate symbolism appear in his much-loved work, The Light of the World (1851-53), probably the most popular religious painting in nineteenth-century Britain and America. Initially, The Light of the World encountered a hostile critical reception: Hunt himself quoted Thomas Carlyle's description of it as a "mere papistical fantasy" (355). But Ruskin spoke out publicly in praise of it in an impassioned letter to the editor of the Times: "I believe there are very few persons on whom the picture, thus justly understood, will not produce a deep impression," wrote the influential art critic. He even added, "I think it is one of the very noblest works of sacred art ever produced in this or any other age." After a shaky start, therefore, the painting became Hunt's first big success. The other work of Hunt's that Ruskin felt called upon to defend at this time was The Awakening Conscience.

Naturally, Hunt was greatly relieved to be championed in this way: "It could not but gratify and encourage me to read these words of high appreciation," he wrote later (419). In fact, this proved to be an important moment in Victorian art: on the one hand, Ruskin's close attention to the iconology of these paintings strengthened his own critical practice, and, on the other, his unstinting praise boosted the whole Pre-Raphaelite enterprise (see Landow 43-45).

In the following year, Hunt set off a two-year visit to Syria and Palestine, where he and fellow-artist Thomas Seddon were profoundly impressed by the experience of seeing Jerusalem, and where he began painting his iconic canvas, The Scapegoat, on the shores of the Dead Sea. It was completed in Jerusalem in June 1855, and would be exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1856. The trip was fraught with perils (even the goat fell sick and died), and it was hard to get suitable models to pose for other paintings, such as his masterpiece, The Finding of the Saviour in the Temple (1854–60). But Hunt, despite having become active as an illustrator, and an important contributor to the "discourse of mid-Victorian graphic art," as Simon Cooke explains in his essay on Hunt's work in this area, was determined to return. He was not put off even when Seddon, who set off again in the October of that year, died in Cairo in December — coincidentally on the very day that Hunt's father was being buried in Highgate Cemetery. Poor Seddon was only thirty-five, and left behind him a young widow and an infant daughter.

The tomb of Fanny Holman Hunt, just below that of Elizabeth Barrett Browning, in the English Cemetery at Florence. [Click for more information.]

Nevertheless, Hunt not only wanted to return to the East, but to get married before doing so. After the long-drawn-out failure of his affair with Annie Miller (the original model for Il Dolce Far Niente in 1860), he married his first wife Fanny Waugh on 28 December 1865. The couple set off in the following August, but were held up en route. Fanny died after childbirth while they were in Florence. Hunt was inconsolable, and designed and supervised the work on her tomb at nearby Fiesole. From Fiesole it was brought down to the English Cemetery in Florence. Hunt's heartbroken mourning for Fanny was expressed in Isabella and the Pot of Basil (1866–8).

Left: Hunt’s Self-portrait in the Uffizi Gallery, Florence, in which he portrays himself in middle-eastern garb. Right: Fanny Waugh Hunt. Hunt’s memorial portrait of his first wife. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

At the end of August 1869, Hunt finally revisited Jerusalem alone, leasing an old house there and beginning work on The Shadow of Death (1870-73). He stayed the best part of three years. Although he was busy, these were lonely years for him. Fanny's sister Edith had already professed her love for him — but they could not legally marry in England because she was his deceased wife's sister. They married in Switzerland in November 1875, and Hunt returned to Jerusalem at last with his new bride, and his son Cyril Benone from his first marriage, staying until July 1878. In 1876 another child was born: Gladys Millais Mulock, the extra middle name taken from the maiden name of her godmother, the author Dinah Craik, who had been present at the wedding.

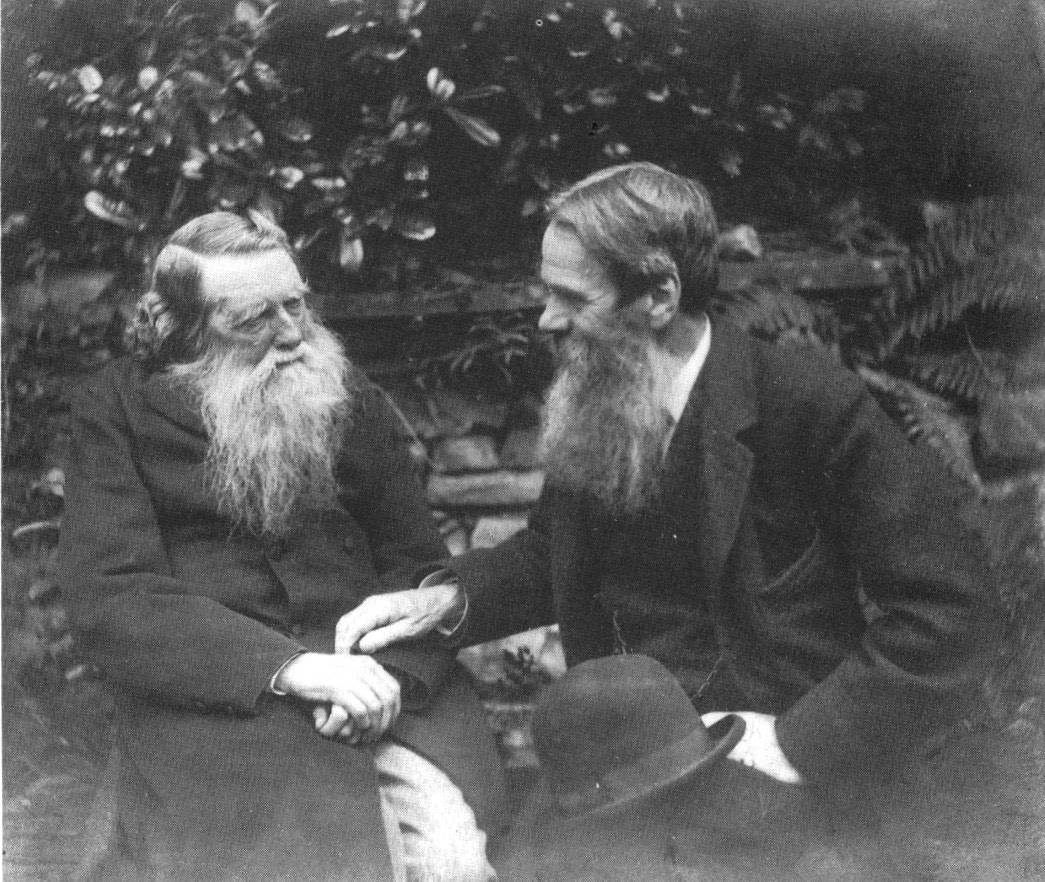

Frederick Hollyer's photograph of John Ruskin and William Holman Hunt at Brantwood, in September 1894.

Edith bore another child, Hilary Lushington, in 1878, on their return to England, and eventually they settled down in a house in the artists' area of Holland Park. Among Hunt's later successes were The Triumph of the Innocents (1885), The Lady of Shalott (c.1886-1905, based on his earlier illustration for the Moxon Tennyson) and May Morning on Magdalen Tower (1889). He was suffering from glaucoma and needed a studio assistant now, a role ably filled by Edward Robert Hughes (1851-1914). His last important work was The Miracle of the Sacred Fire in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, Jerusalem (1892-99) His Light of the World had long since acquired iconic status, and his later version of it (c.1900-04), almost life-size, hangs in St Paul's, where his ashes were buried next to those of Millais, after an impressive ceremony. One of the pall-bearers was Dante Gabriel Rossetti's brother William, and many other grandees from the cultural establishment (including Tennyson) were in attendance.

Bibliography

Amor, Anne Clark. William Holman Hunt, The True Pre-Raphaelite. London: Constable, 1989. (This most enjoyable biography is the main source of factual information here).

"The Author of Modern Painters." The Times. 5 May 1854: 9. Times Digital Archive. Web. 2 March 2018.

Hunt, William Holman. Pre-Raphaelitism and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. Vol. I of II. New York: Macmillan, 1905. Internet Archive. From a copy in the collections of Harvard University. Web. 2 March 2018.

Landow, George P. Ruskin. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985; republished London: Routledge Revivals, 2015. Also available online [here] as a Victorian Web book.

Last modified 12 March 2018