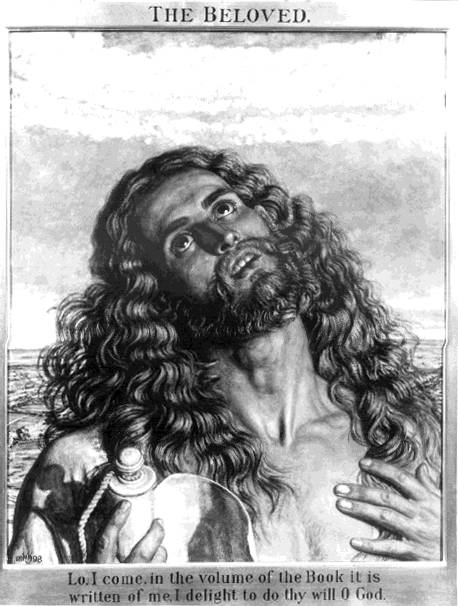

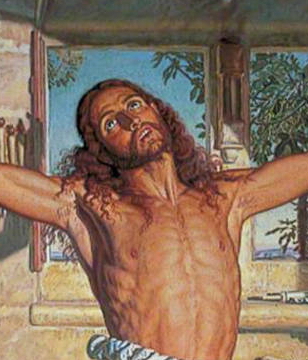

Left: The Beloved>. William Holman Hunt. 1898. Oil on canvas, 24 1/2 x 20 inches. Collection of Her Majesty, the Queen. Right: The Shadhow of Death. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

The Beloved (1898), which began as a commission from the Queen for a copy of Christ's head from The Shadow of Death (1873), again concerns the encounter of man and God. When the picture was exhibited at the Leicester Galleries in 1906, the accompanying catalogue explained that "Her Majesty Queen Victoria expressed an interest in the picture and commanded it to be sent to Buckingham Palace. Her Majesty then desired the artist to make a copy of the head of Christ for the Royal Collection." But when the painter at last began to paint a copy, he realized that "the pose of the arms in the larger work compelled a change of treatment for the limits of the smaller picture." In fact, both the slight change of pose necessary and the omission of most of the original work's iconologically significant details markedly changed the meaning of the resultant copy. although the changes in visual and iconological features are not so obvious as those between The Hireling Shepherd and The Strayed Sheep -- a previous instance of a commissioned partial copy becoming an entirely new work — major differences clearly exist.

By limiting the entire image to that of the ecstatically praying Jesus, The Beloved takes on a mystical emphasis not present in The Shadow of Death. For whether Christ is here understood as the beloved Son of God, a fulfillment of the Psalmist's prefigurative meaning, or a combination of the two, such meaning differs from The Shadow of Death's emphasis upon the sacrifice of Jesus.

Whereas the earlier picture depicts Mary's recognition of her son's fate, the later one provides an image of joyful prayer alone; whereas the earlier picture also stresses the fact of Christ's kenosis or descent into the flesh, making his daily human labor as much a sacrifice as the final prefigured Crucifixion, the later painting presents, in contrast, an image of Jesus ascending toward the divine. The Shadow of Death makes us comprehend the fact that the divine, the eternal, and the omniscient accepted all the painful limitations of humanity: God descended into human flesh. The Beloved, however, presents the movement of the human up to the divine. Since Christ combines man and God, he presents a perfect image of man's potential spirituality in The Beloved. Whereas the primary emphasis of The Shadow of Death remains upon the physical, that of The Beloved is upon the spiritual and mystical. The human, suffering, physical nature of Jesus receives major emphasis in the original picture, while it is the spiritual that predominates in the partial copy.

The Shadow of Death. William Holman Hunt. 1869-73. Oil on canvas, 84 5/16 x 66 3/16 inches. Manchester City Art Galleries. Kindly made available by the gallery (via Art UK under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives licence (CC BY-NC-ND). Right: The Shadow of Death. Oil on canvas, 94 x73.6 cm Leeds Art Gallery, Leeds Museums and Galleries LEEAG.PA.1903.019 Gift from the executors of the estate of C. G. Oates, 1903.

Jesus holds a scroll — just as he did in Hunt's 1886 mosaic design Christ and the Doctors — and reminds us that he has come to fulfill the Law and the Prophets. Presumably Christ, who has been meditating upon the Scriptures, has either understood them as applying to himself as the Beloved, or else, in his prayerful adoration, he repeats and fulfills the acts of David the Psalmist, who was conventionally taken by Victorian and earlier exegetes as a type of Christ. What Hunt has done, therefore, is provide a paradigmatic moment, one in which Christ as human encounters Christ the divine: The historical Jesus confronts himself as Messiah and the Beloved — the divine text confronts its source and origin.Following his characteristic procedure, the artist appended a biblical text to the frame of his painting, which directs us to the context within which he wished his image to be interpreted: "Lo. I come, in the volume of the Book it is written of me, I delight to do thy will O God." This text, which appears both in Psalms 40:7 and Hebrews 10:7, was traditionally taken as one of those in which David speaks with the very words of Christ. Indeed, according to some nineteenth-century commentators on the Psalms, Christ occasionally spoke through David in the manner of a ventriloquist. Of course, even if we are unaware of its conventional typological significance, this text makes clear that Hunt's painting presents a clear instance of Christ's submission to the divine will — and hence an example for all men.

Despite Hunt's obvious general meaning in The Beloved, I cannot precisely identify the particular scriptural text, if any, to which the title refers. The title apparently alludes to the many uses of "beloved" in the Song of Solomon (or Canticles), whose ecstatic tone and subject match that of Hunt's painting. Two texts seem particularly applicable. First, Canticles 2:3 perhaps contains an allusion to the title of the original The Shadow of Death, which depicts Mary looking through the gifts that the Magi had long ago brought in homage to her son: "As the apple tree among trees of the wood, so is my beloved among the sons. I sat down under his shadow with great delight." Such a verbal echo hardly strikes one as close enough to Hunt's views to be entirely convincing as a possible allusion, and a passage from Canticles 5:2 seems more likely: "I sleep, but my heart waketh: it is the voice of my beloved that knocketh, saying, Open to me, my sister, my love ... for my head is filled with dew, and my locks with the drops of the night." Given Hunt's demonstrated preoccupation with The Light of the World at this stage of his career, such echoes of that earlier work strike one as at least possible, but nonetheless very difficult, to demonstrate.

Of course, even if Hunt only intended to create an image of man's ecstatic yearning for God, or of the way in which Jesus encounters the heavenly father in prayer, he has created a work that recapitulates and represents his career-long fascination with moments of conversion, illumination, and vision.

The Beloved (1898), which began as a commission from the Queen for a copy of Christ's head from The Shadow of Death (1873), again concerns the encounter of man and God. When the picture was exhibited at the Leicester Galleries in 1906, the accompanying catalogue explained that "Her Majesty Queen Victoria expressed an interest in the picture and commanded it to be sent to Buckingham Palace. Her Majesty then desired the artist to make a copy of the head of Christ for the Royal Collection." But when the painter at last began to paint a copy, he realized that "the pose of the arms in the larger work compelled a change of treatment for the limits of the smaller picture." In fact, both the slight change of pose necessary and the omission of most of the original work's iconologically significant details markedly changed the meaning of the resultant copy. although the changes in visual and iconological features are not so obvious as those between The Hireling Shepherd and The Strayed Sheep -- a previous instance of a commissioned partial copy becoming an entirely new work — major differences clearly exist.

By limiting the entire image to that of the ecstatically praying Jesus, The Beloved takes on a mystical emphasis not present in The Shadow of Death. For whether Christ is here understood as the beloved Son of God, a fulfillment of the Psalmist's prefigurative meaning, or a combination of the two, such meaning differs from The Shadow of Death's emphasis upon the sacrifice of Jesus.

Whereas the earlier picture depicts Mary's recognition of her son's fate, the later one provides an image of joyful prayer alone; whereas the earlier picture also stresses the fact of Christ's kenosis or descent into the flesh, making his daily human labor as much a sacrifice as the final prefigured Crucifixion, the later painting presents, in contrast, an image of Jesus ascending toward the divine. The Shadow of Death makes us comprehend the fact that the divine, the eternal, and the omniscient accepted all the painful limitations of humanity: God descended into human flesh. The Beloved, however, presents the movement of the human up to the divine. Since Christ combines man and God, he presents a perfect image of man's potential spirituality in The Beloved. Whereas the primary emphasis of The Shadow of Death remains upon the physical, that of The Beloved is upon the spiritual and mystical. The human, suffering, physical nature of Jesus receives major emphasis in the original picture, while it is the spiritual that predominates in the partial copy.

Jesus holds a scroll — just as he did in Hunt's 1886 mosaic design Christ and the Doctors — and reminds us that he has come to fulfill the Law and the Prophets. Presumably Christ, who has been meditating upon the Scriptures, has either understood them as applying to himself as the Beloved, or else, in his prayerful adoration, he repeats and fulfills the acts of David the Psalmist, who was conventionally taken by Victorian and earlier exegetes as a type of Christ. What Hunt has done, therefore, is provide a paradigmatic moment, one in which Christ as human encounters Christ the divine: The historical Jesus confronts himself as Messiah and the Beloved — the divine text confronts its source and origin.

Following his characteristic procedure, the artist appended a biblical text to the frame of his painting, which directs us to the context within which he wished his image to be interpreted: "Lo. I come, in the volume of the Book it is written of me, I delight to do thy will O God." This text, which appears both in Psalms 40:7 and Hebrews 10:7, was traditionally taken as one of those in which David speaks with the very words of Christ. Indeed, according tosome nineteenth-century commentators on the Psalms, Christ occasionally spoke through David in the manner of a ventriloquist. Of course, even if we are unaware of its conventional typological significance, this text makes clear that Hunt's painting presents a clear instance of Christ's submission to the divine will — and hence an example for all men.

Despite Hunt's obvious general meaning in The Beloved, I cannot precisely identify the particular scriptural text, if any, to which the title refers. The title apparently alludes to the many uses of "beloved" in the Song of Solomon (or Canticles), whose ecstatic tone and subject match that of Hunt's painting. Two texts seem particularly applicable. First, Canticles 2:3 perhaps contains an allusion to the title of the original The Shadow of Death, which depicts Mary looking through the gifts that the Magi had long ago brought in homage to her son: "As the apple tree among trees of the wood, so is my beloved among the sons. I sat down under his shadow with great delight." Such a verbal echo hardly strikes one as close enough to Hunt's views to be entirely convincing as a possible allusion, and a passage from Canticles 5:2 seems more likely: "I sleep, but my heart waketh: it is the voice of my beloved that knocketh, saying, Open to me, my sister, my love ... for my head is filled with dew, and my locks with the drops of the night." Given Hunt's demonstrated preoccupation with The Light of the World at this stage of his career, such echoes of that earlier work strike one as at least possible, but nonetheless very difficult, to demonstrate.

Of course, even if Hunt only intended to create an image of man's ecstatic yearning for God, or of the way in which Jesus encounters the heavenly father in prayer, he has created a work that recapitulates and represents his career-long fascination with moments of conversion, illumination, and vision.

Bibliography

Ladies of Shalott: A Victorian Masterpiece and Its Contexts. Ed. George P. Landow. Providence: Brown University, 1985.

Landow, George P. Section on painting in William Holman Hunt and Typological Symbolism

Leng, Andrew. "The Ideology of 'eternal truth': William Holman Hunt and The Beloved, 1850-1905"

The Pre-Raphaelites. London: Tate Gallery/Allen Tate, 1984.

Wood, Christopher. The Pre-Raphaelites. New York: Studio Press, 1981.

Last Modified 25 December 2021