[This was Dallas's second Times review of a folk-tale collection, following his evaluation in February 1859 of Popular Tales from the Norse by G.W. Dasent; here Dallas's childhood in a Gaelic-speaking community in the Scottish highlands perhaps adds a personal touch to the appraisal. - Graham Law]

West Highland Tales

r. Campbell has published a collection of tales which will be regarded as one of the greatest literary surprises of the present century. It is the first instalment of what was to be expected from any fair statement of the scientific value of popular tales. To the translator of the Norse Tales belongs the honour of having fully set the theory of legendary lore before the English public. Interesting as those tales are in themselves, the explanation of their historical value which accompanied them gave them an importance which renders the publication of that work a literary landmark, just as in the last century the publication of Percy's Reliques is another point of departure. The popular tales which we all know to have been once abundant enough throughout these islands acquired a new significance, and it was generally expected that a rich harvest awaited the students who would take the trouble of collecting and classifying the legends which still survive in popular tradition. The first to come forward with his gleanings is Mr. Campbell, who amid his own countrymen, the Gaelic population of the Western Highlands, has evidently made a good day's work of it. He modestly describes his volumes as a museum of curious rubbish, and is no more than just to himself when he immediately afterwards adds that one man's rubbish is another man's treasure. The existence of such treasure as we have here unrolled has long been suspected by all who were intimately acquainted with the Scottish Highlands. The difficulty was to get at it, and to make those persons who possessed it believe that it had any value. Among the educated classes who could find an interest in these tales there are but few Gaelic scholars. Almost all the Gaelic scholars are ministers, who naturally despise such vain imaginations, and teach the people to despise them also. It required some striking demonstration of the real worth of popular tales to arouse Gaelic scholars from their apathy. They have been aroused, and here is the first fruit in a work that is most admirably edited by the head of a family beloved and honoured in those breezy Western Isles, who has produced a book which will be equally prized in the nursery, in the drawing-room, and in the library.

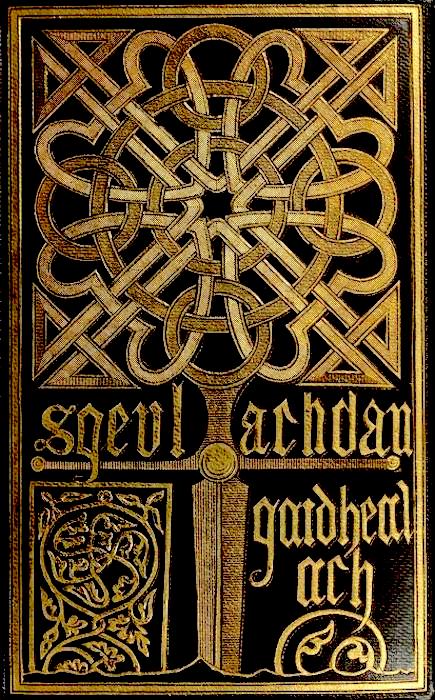

Cover and frontispiece page of Vol. III of Campbell's collection, in an 1860 edition from the National Library of Scotland, in the Internet Archive. The caption to the frontispiece reads, "In what place is thy dwelling, thou lad with thy dress of skins?"

These tales have avowedly been collected in the past and in the present year, since the publication of the Norse Tales; but the author is anxious to make out, and, indeed, he proves it, that though in not a few particulars they resemble those stories, yet they could not have been derived from the translation of last year, and must be ascribed to an independent source. They belong to the people, and are for the most part indigenous. Many of them were collected by Mr. Campbell himself, who is thoroughly conversant with the old language, and the rest by friends whom he set to work. In the table of contents we have a curious list of the persons from whom they were obtained, the persons who took the trouble of reporting them, and the date of the narration. One of the storytellers is a blind fiddler, another a sawyer, another a crofter, and almost all are of the uneducated class?fishermen, stableboys, paupers, drovers, labourers, farm-servants, servant-maids, travelling tinkers, shoemakers, gamekeepers, gardeners, quarrymen, and pipers. It was difficult to get these people to tell the stories, and it was only to persons addressing them in Gaelic that they could be induced to relate what they were half ashamed of. Mr. Campbell seems to have attacked them with great skill and courage, spending many a long hour, and offering many an honest bribe, to wheedle the tales from the people. How he got on with a tinker in London is a specimen of the way in which he got to the right side of many poor fellows in the Highlands. . . . On another occasion Mr. Campbell sits in the lowly cottage of an old man in South Uist, with whom he talks and smokes for hours, waiting till the ebb of the tide permits a passage by the ford to Benbecula. Ducks and ducklings, a cat and kittens, some hens and a baby all tumble on the clay floor together, visible only by the light that streams down the chimney and through a single pane of glass. Other travellers drop in, waiting for the ford to be shallow enough, and all hang upon the strange stories which the old man recites.

The custom is now dying out, but it is still not uncommon for the Highlanders to gather together in each other's cottages, and spend the night in these recitations. . . . [10c]

Link to Related Material

- Myths and Legends in Victorian Culture (sitemap)

- Scottish Highlands and Islands (sitemap)

- Victorian Scotland (sitemap)

Bibliography

[Dallas, Eneas Sweetland]. "West Highland Tales," The Times (5 November 1860): 10c-e. [Review of J. F. Campbell, Seann Syeulachdan Gaidhealach / Popular Tales of the West Highlands, Orally Collected, with a Translation, Edinburgh: Edmonston & Douglas, 1860, Vols I-II.]

Created 2 February 2024