In transcribing the following passage from the online version I have expanded abbreviations, links, a decorative initial letter, and illustrations. All images come from Dent’s The Making of Birmingham — George P. Landow

very curious outbreak of popular opinion, happily unattended by physical force, marked the closing months of the half-century. The establishment in England of a Roman Catholic Hierarchy had aroused popular feeling all over the country against the so-called Papal aggression, and nowhere was it felt more keenly than in Birmingham, where the first Roman Catholic Cathedral had been built, and stood as an outward and visible sign of the ‘advance of Popery.

“The appearance of the streets in November, 1850,” says Mr. Jaffray, “was strange, a large portion of the population seemed to have devoted themselves to writing and chalk. . . . ‘No Popery’ stared from every turning; with somewhat dreamy notions of orthography ‘ No Property’ was the motto of others. ‘ Serve the Priests as they do the Bible—burn em!’ suggested one. ‘ Down with the Cathedral,’ was the advice of another, no doubt a friend of the respectable individual who insisted on ‘No Property.’ A third became philosophical, ‘The Catholics are the ruins of all nations.’ Another waxed theological, and declared that ‘No Catholic, Quaker, Baptist, Independent, or Methodist shall ever enter the kingdom of heaven.’ ‘A curse to the priests,’ was often given. ‘D--------------n Antichrist and all Catholics,’ was no less frequent. An anathema was hurled at Dr. Ullathorne; and was followed by a declaration that ‘we won’t have no kardenels’ nor ‘vicar-apostles.’Some walls, phylacterylike, were covered with passages of Scripture, such as ‘Thou shalt not bow down to graven images’; elsewhere, there were exhortations to }Read the Word of God for yourself,’ and to ‘ Beware of false preachers.’ Some of these street literati were artists as well. A droll cartoon, drawn on the pavement, was said to represent ‘Cardnell Fulishman;’ and an elaborate design for a pair of candlesticks was emblematic of the artist’s determination to ‘have no religion like that.’

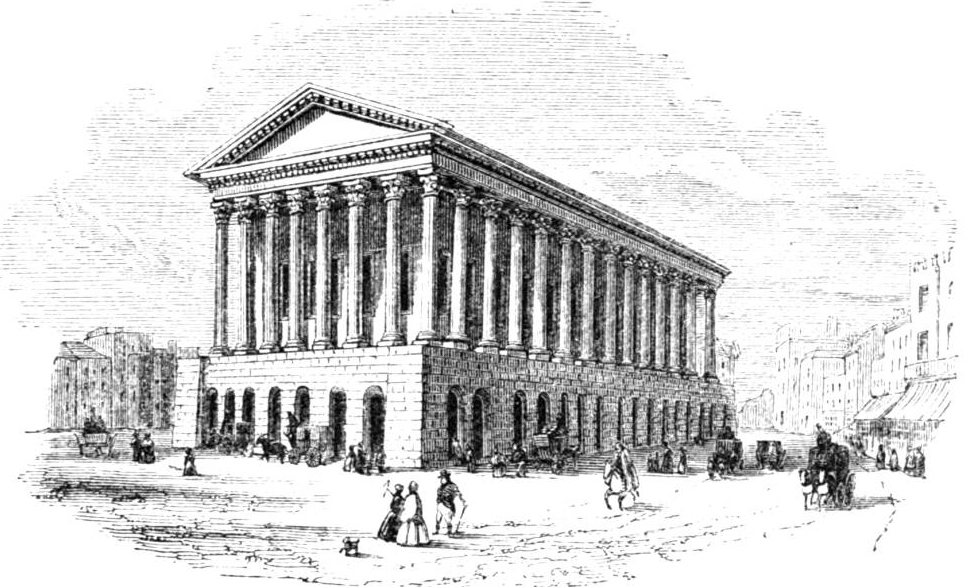

The Townhall, Birmingham. From Nature on Wood by C. W. Radclyffe. Click on image to enlarge it.

This burning question was discussed in a more formal manner at a town’s meeting which was held on the 11th of December in the Town Hall. The greatest excitement prevailed; the building was crammed, and it was estimated that at least 10,000 persons were present. An address to the Queen was moved by one party, protesting ‘against the recognition in this nation of any foreign potentate, as subversive of order, good government, and freedom,’ and praying Her Majesty ‘ to take immediate steps to vindicate the prerogative of the crown, and to maintain the liberties of her subjects.’ This was supported by Dr. Melson, the Rev. John Angell James, and Mr. Spooner, M.P., while an amendment, also in the form of an address to the Queen, expressing the opinion that the appointment of a Roman Catholic Hierarchy in England ‘does not require any legislative interference,’ was moved by Mr. Joseph Sturge, seconded by George Edmonds, and supported by George Dawson and the Rev. Brewin Grant. The discussion was continued for hours, but both the original motion and the amendment were rejected, “and thus,” says Mr. Jaffray, “no voice proceeded from Birmingham on a question considered more important at the time than any other since the days of the Reform Bill and the Anti-Corn-Law League.”

Related material

- Religion in Victorian England (homepage)

- Victorian Political History (homepage)

- Victorian Social History (homepage)

Bibliography

Dent, Robert K. The Making of Birmingham: Being a History of the Rise & Growth of the Midland Metropolis. Birmingham: J. L. Allday, 1894. Birmingham: Hall and English, 1886. 398-403. HathiTrust online version of a copy in the University of California Library. Web. 4 October 2022.

Last modified 11 October 2022