I would like to dedicate this article to Rita Wood, who was so enthusiastic about the many varied aspects of York's history. She originally asked me to write about scoria bricks a year ago, and various pressures since meant that I have only just been able to submit it, too late for Rita to see, sadly.

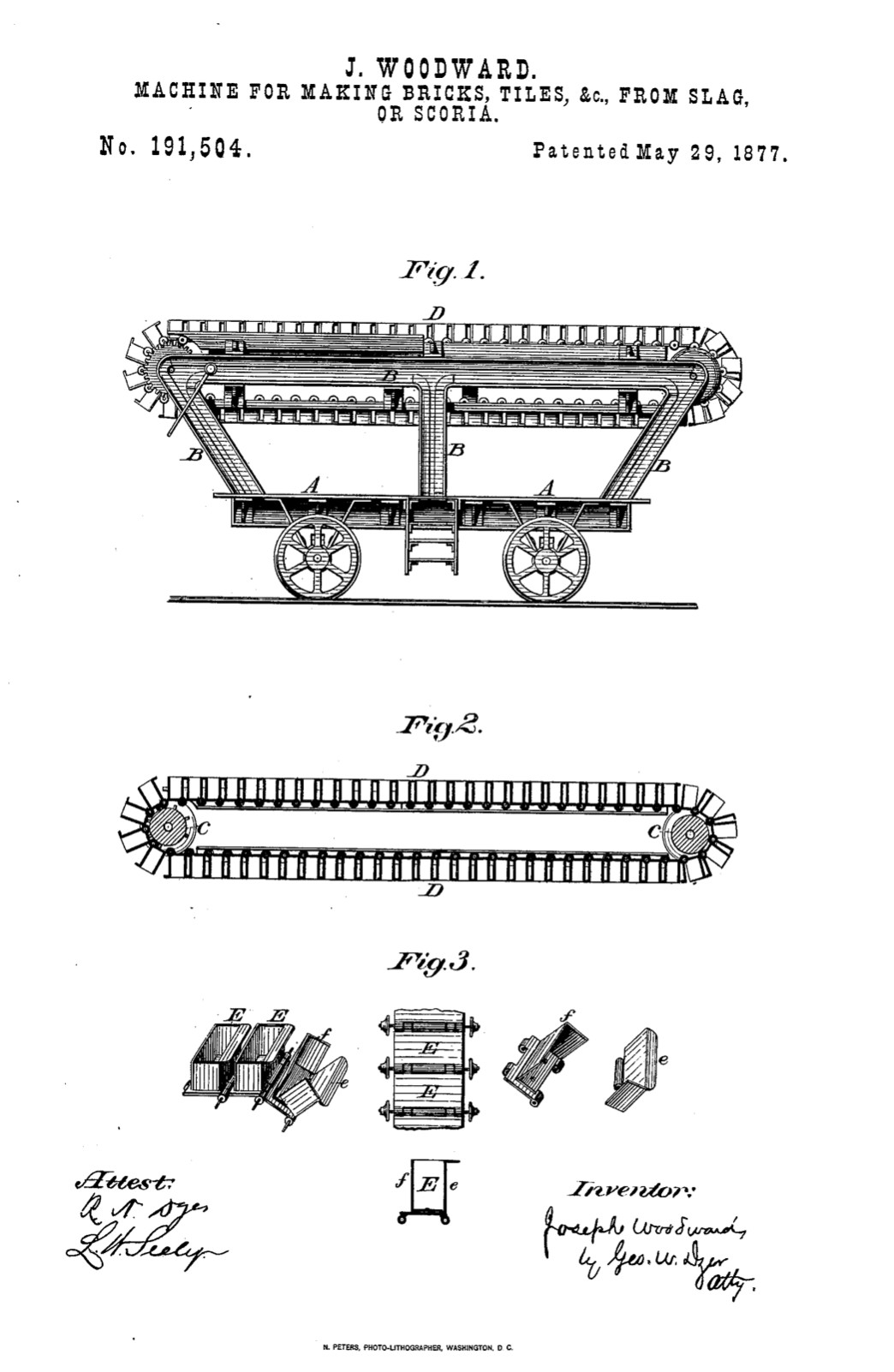

Left, fig. 1: Back alley in South Bank in York, paved with scoria bricks (photo by Sue Gabbatiss). Right, fig. 2: Square blue scoria bricks in back alley in South Bank, York (photo by Susan Major).

The urban back alleys of York feature some very distinctive historic paving bricks, mostly in the form of double hexagons linked together, although some are rectangular or square (figures 1 and 2). These bricks have a shiny silvery blue/grey surface, and in some further cases are used to line street gutters. They feature all over older York areas such as Haxby Road, The Groves, Holgate, Acomb and Heworth. This type of brick is also found in parts of the north east, such as Saltburn, Darlington and Whitby.

They are actually called scoria bricks or blocks. The word scoria is an ancient Greek word, meaning excrement or dung, but the Romans used this word for hot lava bursting out of a volcano. Then it became the name of the refuse left when metal was melted. The story of these bricks starts in the mid-19th century, in the blast furnaces in Cleveland in the North East of England.

Millions of tons of pig iron were being produced, from ore deposits in rock. This generated millions of tons of slag waste at the bottom of the blast furnaces, a real problem for the ironmasters, as it was expensive to remove. Slag was often tipped on waste ground or used to reclaim marsh land. It was sometimes poured over cliffs, for example at Skinningrove. "Basic slag" was used as a fertiliser on fields, even in the 1950s, as it contained lime and released phosphates when buried. There were attempts to make slag cement, building bricks and slag wool, used for insulation, and in modern times it is now used as a building aggregate. Its chemical constituents were lime, silica, alumina, magnesia, sulphur, calcium sulphide, iron, potash, soda and manganese.

It was the manganese compounds which led to its blue colour. There was a famous area of Consett in County Durham called the Blue Heaps, where slag was dumped from the iron works in the mid-nineteenth century. In 1847 it was the scene of what was later called the Battle of the Blue Heaps, a stand-off between Irish Catholic migrant workers and English Protestant workmen, before soldiers were sent to quell the problem.

A smart Victorian idea was to make shiny silvery-blue bricks from slag for a road or alley surface, a really good recycling solution because of its qualities. There were many attempts at this, but getting the slag into the right place, shaping it into uniform bricks and cooling it slowly was full of difficulties. It was Joseph Woodward, a Darlington man, who found the solution in the late 1860s.

Woodward’s process tapped molten slag from the bottom of the blast furnaces and transported it in bogies (trucks) along a railway to the kilns. His invention was a revolving table with moulds (figure 3). The slag was poured into the moulds, and after two minutes, it was still red hot, but set. At the vital moment, the turning motion of the table and a lifting latch tipped the brick out of the mould, to be arranged by an attendant onto a conveyor belt carrying it into a kiln, heated by the furnace. Bricks were then housed in this annealing kiln for three days, until ready to use. Here it was allowed to cool very slowly, in order to remove internal stresses and make it easier to work. This process had to be carefully managed to avoid cracking and to maintain an even texture.

Fg. 3: "Machine for making bricks, tiles, &c., from slag, or scoria" as depicted in Joseph Woodward’s American patent, 1877.

The process produced scoria bricks, a kind of basalt, an igneous rock. These bricks were very hard to break, very durable, completely waterproof, frost-proof and indeed chemical-proof. Much later they proved very useful in drainage channels at ICI Billingham in the 1920s. The alternative to using these bricks on Victorian roads was whinstone setts, which had replaced cobbles. It was found that scoria bricks were cheaper and easier to lay, as they were very regular and identical in size, thus easily laid flat on roads, on a 6in bed of sand, to be compressed down by men with heavy wooden rammers.

Joseph took a patent out in 1869 on his device, and recruited a group of businessmen to form the Tees Scoriae Brick Company, which operated at Clay Lane Blast Furnace in Eston, Middlesbrough in 1872 for this purpose. He was keen to demonstrate his invention. In 1875 he was at the Ripon Agricultural Show, proudly announcing that Darlington Corporation had trialled his bricks successfully for two years in one of their main streets. He exhibited at the Yorkshire Show at Northallerton in 1878, where he paved an area suitable for stables. The company opened factories at Acklam in Middlesborough and Lackenby at Redcar, next to blast furnaces. They later expanded their location at the Cargo Fleet Iron Works at South Bank in Middlesborough. Woodward also took out an American patent (see figure 3).

There were several brick patterns, to be found all over the North East back alleys. Investigations have revealed that many of the York alleys were paved with the bricks in the late nineteenth century, and used for example in the approaches to the new railway station at York, which opened in 1877, also at Edinburgh. Darlington was similarly well-endowed with these bricks. Huge quantities were manufactured on Teesside, and many were exported to Canada and the West Indies, as well as Holland, Belgium, the US, South America and Africa. There were a few production problems, such as the downtimes in iron works. Eventually however the motor car destroyed the business, when it replaced metal-rimmed carriages, as people wanted a smoother ride, and tarmac started to follow in the 1930s. Steel and iron making ran down and by 1966 the Company went bankrupt, to be wound up in 1972.

Sadly now in York, many alleys have been excavated for utilities and street lighting, with scoria bricks patched with tarmac, as they are no longer available for replacement.

Researches into the background of Joseph Woodward (1824-1888), who played such a significant role in York’s urban landscape, reveal an intriguing man, who moved around the country, changing his occupation and businesses, his residences, and sadly losing a number of wives. But he was able to use his reputation as a Wesleyan preacher to attract supportive networks and capital. Scoria bricks solved a serious problem for iron manufacturers on Teesside, in removing and recycling waste, at a time when urban areas were expanding and building many new roads and houses.

Bibliography

Major, Susan. "Scoria bricks in the back alleys of York." York Historian. 41 (2024): 38-54.

Morris, Charles, "Scoria blocks." Cleveland Industrial Archaeologist. 13 (1981): 23–32.

Note: Clements Hall Local History Group is currently mapping the location of these bricks in York: see https://www.clementshallhistorygroup.org.uk/blog/scoria-bricks-do-you-have-them-in-your-neighbourhood

Created 4 February 2024