These letters graciously have been shared with the Victorian Web by Eunice and Ron Shanahan; they have been taken from their website. The letters give an insight into the daily lives and concerns of 'ordinary' people without whom history would not exist. The letters are a wonderful example of how much history may be gleaned from such sources.

I collect these old letters for the postmarks, and as there is just no way I could obtain many of the really scarce postmarks, like most stamp collectors, I have had to impose limits. I have specific interests which tempt me to buy the items from dealers and auctions — my particular limits are places I have lived, or some type of mark — for instance the "TOO LATE", "MILEAGE MARKS", and "SHIP LETTER MARKS", and the various London Post marks.If I buy an item with a good postmark, I am doubly pleased if the content of the letter is also interesting.

I have two letters from Bristol Penny Post, dated 1824, showing different Penny Post Office numbers. The Bristol Penny Post was the second Provincial Penny Post in England, after Manchester, opened in July 1793 — it covered a large area and had 57 sub offices.

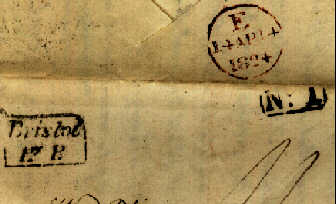

The first letter is dated April 12th, 1824, and addressed to Wm Phillips Esq 23 Cavendish Square London, from T Hensman, 7 Dowry Square Hot Wells. It has four postal markings: —

- a boxed two-line Bristol Py.P in black — in use from 1822 — 1828

- a boxed No.1 stamp of Bristol Penny Post Receiving Office — őHot Wells‚. This was originally at the New Inn, Dowry Square, Hotwells, so Mr Hensman would not have had to go far to put his letter in the post

- a manuscript charge mark 11 — to show the amount of postage to be collected from the addressee and finally

- a red circular morning duty date stamp 14 April, 1824, applied by the Inland Office in the London General Post . This has the date on either side of the month and was in use there from 1810 to 1840.

The letter is a short note to explain some financial dealings, but it has a P.S. that says " I find I am too late for Post today, that must detayn this till tomorrow".

The Bristol mailcoach started in 1784. It was the first mailcoach run and it convinced the government to change from foot and horse posts to coaches. The mailcoach took 16 hours to complete the 122 mile journey to London — a full day less than the old method. It had a long and successful history. In one of my reference books "Mail-Coach Men of the Late Eighteenth Century" by Edmund Vale, there is a copy of the Time Bill given to the Guard, with the timings and distance for the journey in 1797. Thomas Hasker, the Surveyor and Superintendent of Mail Coaches attached a note to the time bill explaining that

In winter the Bill is made to arrive at ¾ past 7, but we do not expect it till 8 for their agreement is to work it up in 16 hours, which, as the clocks are slowest at Bristol, will not bring it to London till about a ¼or 20 mins after eight. Very great exertion — 122 miles in 14 hours and ¾, and not less than 1 hour & ł lost in changing horses and supping exclusive of any trifling delay such as losing shoes, breaking a trace &c, some of which happen every journey.

The coach left Bristol at 4 pm, and arrived in London at 8 am the next day. This bears out Mr Hensman‚s note that his letter would not catch the mail. He wrote it on the 12th, it would have been on the mailcoach on the 13th, and arrived in London on the 14th.

The second letter is dated Sepr 16th, 1824 from Harriet

Whish, 13 Crescent, Clifton addressed to W.G. Daniel Tysson, Esqre, Foley House,

MAIDSTONE, Kent. Three of the postmarks are of the same type as the previous

letter.

- Boxed Bristol Penny Post, manuscript charge mark of 11d and

- a circular London General Post morning duty stamp in red for transfer to Kent, but this one is dated 17 September 1824.

- The Receiving office stamp however, is a boxed No.2. (Fig. 5) This was allocated to the Clifton Receiving Office.

The letter itself is a lovely chatty informative scribble to her nephew, who she addresses most formally as

My Dear Sir‚

I have already received a notice from Mrs Arniel that their money will be most acceptable at the time, which is the 25th of this month. My payment to her this time is only 3£, as last time, for want of 1£ notes, I was obliged to send her 5£ instead of 4£. Will you then be so good as to advance the 3£ for me, and I will repay it to you with many thanks, by my daughter Mrs. Metcalfe, who will, I have no doubt, come through here to see her little boy, on her way to London the beginning of the next month.

I heartily hope yourself and dear Caroline, and all your family wherever dispersed are in good health, and enjoying themselves this lovely Season.

We have just been changing our house from 36 to 13. Upon the whole I think we are rather better off. At least we are in a clean house, which is a comfort.

My dear Husband is thanks be to God in good health but his mind is sadly gone which is a melancholy thing for us to see! But alas we must be happy that he does not seem in the least sensible of his loss! I am sorry to say that I am a good deal of an Invalid just now, and I am sure I cannot afford to be so, for my good man requires all my attention.

A letter directed to Mrs Arniel Southampton will I conclude be sure to find her — pray my dear Mr D. Tysson either write to me yourself, to acknowledge this, or employ your daughter Caroline to tell me how you all do, for I never hear anything of you but by the merest acident. The Metcalfes have been staying here two months and she recovered very much during that time. They are now at Cheltenham where she has not been so well again and my daughter who is by no means in a good state of health, is there with her. We had hoped the waters would have been of use to her, but they do not seem to have been so. Adieu my dear Mr. D. T. Ever your affectionate Aunt, Harriet Whish

We all unite in warmest love to you all

Concerning this reference to taking the waters — it is easy to take for granted our present public & personal health standards — but life was not like that in the 19th century. Good health was more good luck, in where and how you lived, and there were many őalternative health‚ cures, such as mineral waters. Many towns grew up around the provision of these waters, promoted as bringing good health, and the public flocked to them. Bath, Cheltenham, Harrogate, Leamington all became prosperous towns. The waters contained many different minerals and salts such as iron and magnesium, and the general belief was that if it tasted nasty it was good for you. Well, I have tasted the waters at Bath, which were known well before the Romans developed the city as the health spa — Aqua Sulis — and I felt that őthe cure was worse than the disease‚. That there were others who felt the same is shown by this anonymous pseudo-epitaph

"Here lies I and my three daughters

Dead by drinking Cheltenham waters.

If we‚d stuck to Epsom Salts,

We wouldn‚t be lying in these here vaults.

3 December 2002