This is an excerpt from the Conclusion of Imperial Nature: Joseph Hooker and the Practices of Victorian Science (University of Chicago Press, 2008). Having focused above all on Hooker's practices, the author now explores and explains the ambiguities in his post-Darwinian writings, arguing that he nevertheless found the concept of natural selection useful on several levels. The excerpt has been formatted for the Victorian Web by kind permission of the author, with added illustrations, captions and links. Where possible, in-text citations replace end-notes; page changes are noted in square brackets; and omissions are marked by ellipses in square brackets. [You may use the images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the source and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one. Click on the images to enlarge them.] — Jacqueline Banerjee

o, was Hooker eagerly waiting to make use of his friend's theories, or was he a late convert, only reluctantly pinning his colors to the Darwinian mast? I want to argue that the simple answer is "neither," because asking when Hooker became a Darwinian is asking the wrong question. "When was Hooker converted?" is a product of the popular myth of the Darwinian revolution, the idea that the world changed abruptly in 1859; it is like asking how Darwin was able in a single book to persuade his fellow Victorians to change their minds and accept evolution. Again, the simple answer is that he did not; a huge range of complex factors were at work in the first half of the nineteenth century that made Darwinism attractive to various Victorian communities, including some, but not all, naturalists. The more important question, I would suggest, is "what made natural selection useful to Hooker?" not least because this question reminds us that the practices and debates that shaped Hooker also shaped Darwin. Instead of dividing the world of nineteenth-century natural history into static or anachronistic groups such as professional or amateur, it can be more helpful to think about communities who shared common practices [320/321] (Schaffer). In one sense, Hooker and Darwin were members of the same community, one that practiced classification plants for Hooker, barnacles for Darwin and they both did so in the metropolis (at least, Down was no further from London than Kew was). Given the complex concerns and interests of this community, it comes as no surprise to discover that both Darwin and Hooker saw classification as vital to larger philosophical issues, especially distribution, nor that they both used the natural system, disliked splitters, and were concerned with the stability of classification

and nomenclature: as Gordon McOuat has shown, Darwin was an enthusiastic supporter of of Hugh Strickland's attempts to impose a stable classificatory system. However, there were equally important differences between them: classification occupied all of Hooker's adult life but only eight years of Darwin's (1846-54); Hooker worked in a large, government-funded

institution, Darwin classified at home; Hooker built up and maintained a

vast collection of specimens, Darwin borrowed most of his. However, this

division is not exhaustive: Hooker and Darwin also belonged to different

communities in that their systematic work was botanical/distributional

and zoological/anatomical respectively (communities that do not map on

to the rst ones). Other contrasts could also be drawn.

o, was Hooker eagerly waiting to make use of his friend's theories, or was he a late convert, only reluctantly pinning his colors to the Darwinian mast? I want to argue that the simple answer is "neither," because asking when Hooker became a Darwinian is asking the wrong question. "When was Hooker converted?" is a product of the popular myth of the Darwinian revolution, the idea that the world changed abruptly in 1859; it is like asking how Darwin was able in a single book to persuade his fellow Victorians to change their minds and accept evolution. Again, the simple answer is that he did not; a huge range of complex factors were at work in the first half of the nineteenth century that made Darwinism attractive to various Victorian communities, including some, but not all, naturalists. The more important question, I would suggest, is "what made natural selection useful to Hooker?" not least because this question reminds us that the practices and debates that shaped Hooker also shaped Darwin. Instead of dividing the world of nineteenth-century natural history into static or anachronistic groups such as professional or amateur, it can be more helpful to think about communities who shared common practices [320/321] (Schaffer). In one sense, Hooker and Darwin were members of the same community, one that practiced classification plants for Hooker, barnacles for Darwin and they both did so in the metropolis (at least, Down was no further from London than Kew was). Given the complex concerns and interests of this community, it comes as no surprise to discover that both Darwin and Hooker saw classification as vital to larger philosophical issues, especially distribution, nor that they both used the natural system, disliked splitters, and were concerned with the stability of classification

and nomenclature: as Gordon McOuat has shown, Darwin was an enthusiastic supporter of of Hugh Strickland's attempts to impose a stable classificatory system. However, there were equally important differences between them: classification occupied all of Hooker's adult life but only eight years of Darwin's (1846-54); Hooker worked in a large, government-funded

institution, Darwin classified at home; Hooker built up and maintained a

vast collection of specimens, Darwin borrowed most of his. However, this

division is not exhaustive: Hooker and Darwin also belonged to different

communities in that their systematic work was botanical/distributional

and zoological/anatomical respectively (communities that do not map on

to the rst ones). Other contrasts could also be drawn.

The most important difference was that Hooker earned his living from classification, whereas Darwin did not need to. Darwin was wealthy enough to display a disinterested curiosity about barnacles, pigeons, orchids, primulas, earthworms, or indeed anything else that caught his fancy, including the origin of species; his speculations might hurt his reputation or his wife's feelings, but they could not hurt his income. Hooker, as we have seen, was in a very different position, dependent on government largesse, his father's patronage, and, more importantly, his network of colonial collectors: without them, he had no specimens; without specimens, he could not publish; without books, he could not build his reputation; and without a reputation, he had no chance of obtaining the kind of paid position he required.

Identifying these differences in Hooker and Darwin's communities of practice allows us to see both how Hooker used Darwin's ideas and why that usage created the apparent ambiguities in his essays.

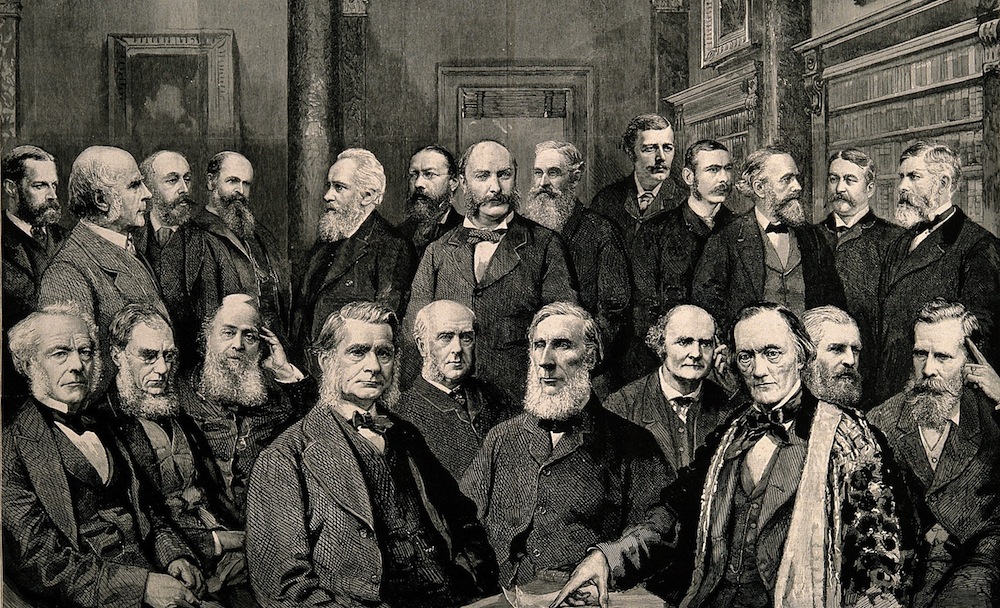

Fellows of the Royal Society in 1888. By kind permission of the Wellcome Library, London. Among many other famous names, the current president, mathematician and physicist George Gabriel Stokes, sits far left; Hooker is seated next to him; T. H. Huxley, another former president and Darwinian, is seated fourth from the left; the eugenicist Francis Galton stands just behind Hooker; seated centre foreground is physicist Professor John Tyndall, and next to him, pointing at the paper on the table, is the paleontologist, Richard Owen. This was the year in which Hooker and Owen were the first gold medallists of the Linnean Society, an award instituted on the centenary of its founding.

One very important source of the apparent ambiguity in Hooker's writing was the conventions of gentlemanly behavior that governed such speculations; as we have seen, when the Earl of Rosse gave Hooker the Royal Society's medal, he praised "the cautious and philosophical manner" in which the subject of species was treated. As Hooker had written, "I am very sensible of my own inability to grapple with these great questions, of the extreme caution and judgment required in their treatment, and of the experience necessary to enable an observer to estimate the importance [321/22] of characters whose value varies with every organ and in every order of plants" (Hooker, Introductory Essay, i-ii). Such caution and care were the hallmarks of the respectability betting a gentleman.

For men from Hooker's community, those who practiced classification for a living, the species question was not primarily about the transmutation of species but about their definition. As he noted, to anyone who has studied botanical classification it "cannot but be evident that the word species must have a totally different signification in the opinion of different naturalists" (Hooker and Thomson 19). And as we have seen, in broaching this topic he constantly needed to deter his colonial audience from speculating. It is not therefore surprising that on the very page where he praised Darwin for providing "more philosophical conceptions," Hooker stressed the need for all botanists to employ "the same methods of investigation and follow the same principles." Whatever their "philosophical conceptions," each botanist must use the same method of classification; as Hooker put it, "the descriptive naturalist who believes all species to be derivative and mutable, only differs in practice from him who asserts the contrary, in expecting that the posterity of the organisms he describes as species may, at some indefinitely distant period of time, require redescription"(Hooker, "On the Flora of Australia," iv [emphasis added]). In other words, even to an evolutionist species were stable over such long periods that they could still be treated as "definite creations" for classificatory purposes. As Hooker had written before the Origin appeared, the difference between transmutationists and their opponents "is very wide perhaps, but not so wide as to allow of their employing different methods towards the advancement of Botany in any one of its departments" (Hooker, "Notice," 255).

In his essays Hooker stressed the continuity of his practices, even though his view of the transmutation question was apparently changing. One strategy for emphasizing continuity was to refer to Darwin's theory as "the hypothesis that it is to variation that we must look as the means which Nature has adopted for peopling the globe with . . . species." Characterizing natural selection as the "variation" theory, as Hooker often did, was important he had always maintained that species were variable; it was the key tenet of his broad species concept. Calling natural selection the variation theory emphasized its continuity with his earlier views; as he noted in the Flora Tasmaniae: "my own views on the subjects of the variability of existing species" remain "unaltered from those which I maintained in the 'Flora of New Zealand'" ("On the Flora of Australia," iii-iv*). So successful was Hooker at stressing the continuity of his views that, after reading both the Origin and the Flora Tasmaniae, Bunbury observed that, while it was "a great triumph for Darwin" to have converted both "the greatest geologist of our time and [322/23] the greatest botanist" (i.e., Charles Lyell and Joseph Hooker), he nevertheless concluded that, although Hooker "adopts the Darwinian theory," he "considers it not as proved, but as a hypothesis, quite as admissible as the opposite one of permanent species, and far more suggestive" (in a letter to Leonora Pertz of 6 March 1860, 154).

At the Darwin Centenary in June 1908: Sir Joseph and his wife, Lady Hooker, with Mrs T. H. Huxley holding Darwin's great-granddaughter Ursula (Huxley II: facing p. 468). Hooker described himself on this occasion as "living in the heart of the Darwin family as a brother" (qtd. in Huxley II: 468), and his obituary from Kew Gardens ("Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker") described him as "the central figure of the occasion" (17).

If we read every Victorian discussion of species in the light of the post-Darwinian world, there is a strong tendency to confuse stable species with divinely created ones. Hooker told Darwin in 1845 that "those who have had most species pass under their hands as Bentham, Brown, Linnaeus, Decaisne & Miquel, all I believe argue for the validity of species in nature"; Richard Bellon cites this as evidence that, at this early stage in his career, Hooker believed species to be divinely created (4). That is certainly a possible interpretation but not, I would argue, the most plausible one, since Hooker went on to write that these distinguished naturalists had all refused to pay attention to the unimportant features of organisms that were "taken advantage of by the narrow-minded studiers of overwrought local oras," that is to say, provincial splitters. Hooker made the comments in the course of their discussion of Frédéric Gérard's work on species, which was mainly concerned with deciding who was entitled to pronounce on the topic. Hooker, as we have seen, dismissed Gerard as typical of those "who have no idea what thousands of good species their [sic] are in the world," someone who "evidently is no Botanist." As early as 14 September 1845, Hooker's main preoccupation was with the stability of species and how to protect them from the splitters, "the narrow-minded studiers of overwrought local floras" (Burkhardt et al. 250). In an 1858 letter to [Asa] Gray, Hooker described one of his chief goals in the introductory essay to the Flora Tasmaniae as being "to harmonize the facts drawn out with the old Creation doctrine & the new Natural Selection doctrine" (qtd. in Porter 32-33). Like the earlier letter to Darwin, this strongly suggests stability was the main issue; assuming each species was specially created was one argument that achieved this goal, but Hooker was wedded to the goal, not the argument. Thanks to the stately pace of Darwin's slow, gradual Version of evolution, natural selection did not undermine stable species, while its "more philosophical conceptions" could enhance the importance of Hooker's endeavors.

Conceptions that were more philosophical would help Hooker gain respect in the metropolis and compliance in the colonies, but they would also help Hooker earn a living as a philosophical botanist. Yet the need to earn a living meant Hooker had to minimize natural selection's potentially destabilizing effect on classification — hence his careful equivocation over natural selection's impact, which has been misinterpreted by some as a lack of enthusiasm. [323/324]

[...] In practice, Darwin's ideas had many positive implications [....] Not only did natural selection allow the botanist to finally stop worrying about how to delimit species and varieties (as Darwin had noted, the latter were simply incipient species anyway), but it also allowed the distribution of numerous "very closely allied" species to be treated as "that of one plant" (Hooker, "Outlines of the Distribution of Arctic Plants," 278-79). What more could even the most ardent lumper ask for? Not only did Darwinism not threaten Hooker's species concept, but it provided it with a firmer philosophical underpinning.

* While he was writing the Flora Tasmaniae essay, Hooker described the Indian botanist George Thwaites as having been a "devoted variationist"; J. D Hooker to Bentham, 17 July [1859], Royal Botanic Gardens Archives: KEW (IDH/2/3). Parts of this letter are quoted in Huxley I: 484. George Henry Kendrick Thwaites worked at the botanic gardens, Peradeniya, Ceylon, from 1849 to 1880 (Desmond 1994).

Related Material

- Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker, Victorian Botanist and Plant Collector

- Botany for Victorian Ladies, Gentlemen and Others

- The Gentleman

- Charles Darwin (1809-1882) gentleman naturalist

- Charles Darwin and the Intellectual Ferment of the Mid- and Late Victorian Periods

Sources

[Source of text:] Endersby, Jim. Imperial Nature: Joseph Hooker and the Practices of Victorian Science. London: University of Chicago Press, 2008.

Bellon, Richard. "Joseph Hooker Takes a 'Fixed Post': Transmutation and the 'Present Unsatisfactory State of Botany,' 1844-1860." Journal of the History of Biology 39: 1-39.

Bunbury, Charles James Fox.

Burkhardt, Frederick, et al., eds. The Correspondence of Charles Darwin. Vol. II, 1863. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

Desmond, Ray. Dictionary of British and Irish Botanits and Horticulturalists, Including Plant Collectors, Flower Painters and Garden Designers. London: Taylor and Francis and Natural History Museum, 1994).

Hooker, Joseph Dalton, and Thomas Thomson. Introductory Essay to the "Flora Indica." London: W. Pamplin, 1855.

Hooker, Joseph Dalton. Introductory Essay to the "Flora Novae-Zelandiae." London: Lovell Reeve, 1853.

_____. "Notice of Alphonse de Candolle's Geographié de botanique raisonée." Hooker's Kew Journal of Botany 8: 248-56.

_____. "Outlines of the Distribution of Arctic Plants." Transactions of the Linnean Society of London 23: 251-348.

_____. "On the Flora of Australia" (introductory essay to Flora Tasmaniae). London: Lovell Reeve, 1859.

Huxley, Leonard. Life and Letters of Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker, Vol. I . London: John Murray, 1918.

[Illustration source:] Huxley, Leonard. Life and Letters of Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker, Vol. II . London: John Murray, 1918. Internet Archive. Contributed by University of California Libraries. Web. 16 April 2015.

McOuat, Gordon. "Species, Rules and Meaning.: The Politics of Language and the Ends of Definitions in 19th Century Natural History. Studies in the History and Philosophy of Science. 27, no. 4: 473-519.

Schaffer, Simon. "Priestley's Questionss: An Historiographic Survey." History of Science 22: 151-83.

[Caption material source:] "Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker. 1817-1911." Bulletin of Miscellaneous Information (Royal Gardens, Kew). Vol. 1912, No. 1 (1912): vi + 1-34. Accessed via Jstor. Web. 16 April 2015.

Created 16 April 2015