This article has been peer-reviewed under the direction of Professors Mary Elizabeth Leighton and Lisa Surridge (University of Victoria). It forms part of the Great Expectations Pregnancy Project, funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

Before reliable tests, which emerged from endocrinological research at the end of the nineteenth century, pregnancy was not always easy to diagnose. Pregnancy diagnosis was a fraught topic in obstetrical writing before the early twentieth-century leap in testing technologies. The audio file that accompanies this article represents a single sentence about pregnancy diagnosis from An Exposition of the Signs and Symptoms of Pregnancy (1837) by Irish obstetrician William Fetherstone Montgomery (1797–1859).¹ The sentence is long at two hundred and eighty-five words; its torturous qualifying clauses testify to the anxiety evoked by its topic:

I am convinced that many of the errors which have been committed, both in theory and practice, have arisen, far less from the acknowledged difficulty of the investigation, than from the want of proper information, and the careless way in which examinations are conducted; for, although we shall occasionally meet with cases so complicated that the best exertions of our judgment, assisted by experience and the possession of the requisite dexterity in the different modes of examination, will still leave us unable to do more than arrive at a result so involved in doubt, as to forbid our attempting to hazard anything approaching to a decisive opinion, such cases are infinitely less frequent of occurrence, than one would be led to conclude, who judged from the number of mistakes made on the subject; such extreme difficulty can, in general, only be encountered during the early months, and, even then, an examination conducted with sufficient attention and care will always enable the practitioner to avoid giving an erroneous opinion; and where blunders have been committed at more advanced periods, they have always in my opinion, been caused by ignorance, want of care, prepossession, or a perverse and short-sighted reluctance to acknowledge, frankly, the inability to decide positively, under circumstances of unusual obscurity: which avowal, exclusive of the imperative necessity of acting honestly, is surely much less humiliating, as well as less likely to detract from our reputation, than to venture, precipitately, on an opinion for which, we must know, we have not sufficient grounds, or through a vain affectation of superior discernment, to pretend to an accuracy of knowledge which the circumstances before us really do not admit of, and which, the event is to belie. [Montgomery 29]

Montgomery’s sentence is tangled by the question of epistemology, that is, by how a pregnancy can be known. In it, he tries to distinguish between the ambiguity generated by insufficiencies of skill or knowledge in the diagnosing practitioner and the ambiguity produced by true uncertainty. The paradox of true uncertainty represents the troubling limit of medical knowledge, and, by extension, that of the law.

The nineteenth century saw the systematic codification of medical jurisprudence, within which pregnancy was a sizeable concern. Medical professionals needed to disambiguate pregnancy from other ailments so that they could prescribe medical treatments or obstetric care, but they were also recruited in legal arenas to detect, sometimes in retrospect, concealed, denied, or feigned pregnancies. Doctors’ opinions might be called on, for example, in cases of contested paternity in title and property disputes, or in criminal cases of suspected infanticide.² Pregnancy was not only a private matter; the state relied on medical evidence to establish lines of responsibility for the children of poor unmarried women.³ Increasingly in the nineteenth century, the “juries of matrons,” who had previously been called on to decide in capital cases whether a woman was pregnant and should have a stay of execution, were being phased out in favour of male medical professionals.⁴ Montgomery’s sentence testifies to the risk of public exposure associated with pregnancy misdiagnoses. The potential for professional humiliation and reputational damage was a key driver in the development of diagnostic techniques. Before there was anything that we would call a “test,” a conspectus of signs and symptoms were identified and categorised—as in Montgomery’s book—and work was underway to establish which were fit for medical and forensic purpose.

The hunt for objective pregnancy knowledge was nakedly situated by practitioners as necessary for evading women’s unreliability in hard-going medico-legal terrain. Either women did not know, told lies about, or were so invested in fictions about their condition, so the story went, that it was hopeless talking to them. Montgomery, for example, warned: “It usually happens in such cases that he [i.e., a medical examiner] cannot rely on a single statement made by the individual who may be the subject of examination; but, on the contrary, he must be prepared for every species of falsehood and misrepresentation” (Montgomery 30). Dreams of pregnancy testing and other ways of achieving certitude were motivated by the desire to lift physicians out of legal and professional jeopardy, rather than give women knowledge about their bodies, futures, or families.

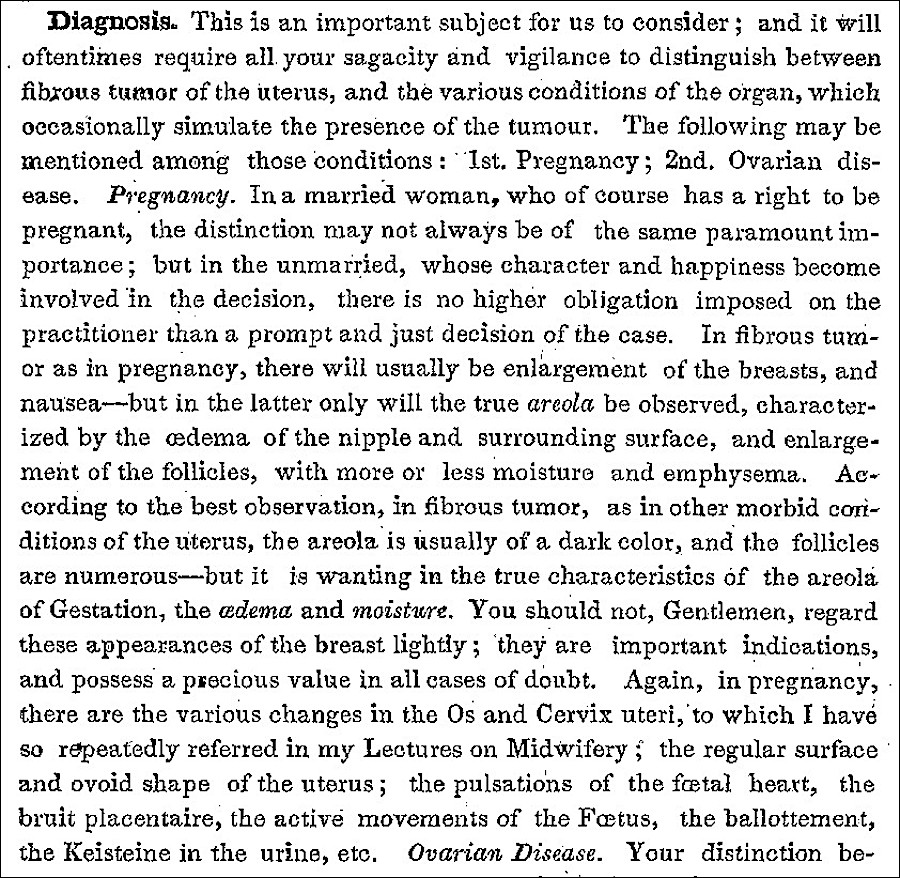

19th-century strategies for the diagnosis of pregnancy. Excerpt from Nelson (p. 71).

An example is seen in the work done on kiestéine. Kiestéine was a technical term coined in the 1830s for the pellicle or skin which had long been described as forming on the urine of pregnant women. Various research trials across Europe and America in the 1830s and 40s investigated its value as a diagnostic tool for pregnancy.⁵ Whilst Montgomery can make nothing of it, others were more adept kiestéine readers. For example, in Philadelphia Hospital in 1841–42, Elisha Kent Kane (1820–57)—better known to history as an Arctic explorer—conducted experiments using the urine of patients who were possibly pregnant or immediately postpartum and lactating (see Kane). Kane’s tabulated results confirmed whether a pellicle could be detected and, if so, after how many days. Kane invariably found kiestéine in the urine of pregnant women and sometimes in that of lactating women. In addition, Kane gives nine longer narrative histories of hard cases. In these narratives, we sometimes learn the woman’s name, her age, whether she had other children, and the ward of the hospital in which she was being treated. In some cases, we know that these women were Black or White because wards were colour segregated. Beyond these sparse details of women’s lives, Kane is concerned with how to use kiestéine to differentiate between true and false pregnancies.

To give a sample: the first on Kane’s list, Helen Anderson, was being treated for gonorrhoea and her sexual habits are described pejoratively as “promiscuous” (Kane 34). Kane successfully diagnosed her pregnancy, and she went on to give birth prematurely. A second woman, Isabella Smith, seemed to have a well-advanced pregnancy, but an internal examination was impossible because of her epileptic seizures, which resulted in “her temporary removal to the women’s lunatic asylum” (35), where Kane acquired a urine sample (presumably under duress). Kane’s kiestéine observations satisfied him “that she was an imposter” (35). Then, “during a well simulated paroxysm of epilepsy, her dress gave way, and disclosed an abundant mass of hair padding ingeniously arranged over the abdomen” (35). A third, Maria Hero, was just fifteen; she borrowed urine samples from her neighbour to hide her condition. Kane showed no concern for his test subjects and the personal circumstances that brought them into his data set. Instead, he was triumphant at being able to see through women’s deceptions or ignorance. He measured his success by the admiration of his male colleagues who sent him samples in the post “under fictitious names, and at a distance of two miles from the place where they were voided” (36), marvelling at his ability to pull off the pregnancy diagnosis trick.

Of the nine women in Kane’s narratives, three were pregnant and wished they weren’t, like Helen Anderson and Maria Hero. Two others were not and knew it, like Isabella Smith. But there were as many as four who believed themselves to be pregnant, in whom “the evidences of pregnancy were well marked” (36), but whose supposed pregnancies Kane was able to determine to be false. The longest of Kane’s case-note entries concerns thirty-seven-year-old Mary Welsh. She had strong pregnancy symptoms; milk had even come into her breasts. She was examined internally and externally multiple times; doctors, including Kane, listened with a foetal stethoscope for a uterine “souffle” or foetal “pulsation” (35). But all these investigations proved inconclusive. Kane’s observations of her urine convinced him that she was not pregnant; “much against her own wishes and those of her fellow patients” (35), he discharged her to the female working wards. Welsh was still undelivered of her false pregnancy perhaps as much as a year after she began to show symptoms, confirming Kane’s diagnosis (but not indicating what lay at the root of these symptoms).

Whatever confidence and clarity kiestéine gave Kane, however, it did not become a trusted sign. Despite the word kiestéine becoming part of a modern technical lexicon, the practice of reading it was dismissed as historical urine inspection under a different name. Selmar Aschheim (1878–1965), who developed the first animal pregnancy test with Bernhard Zondek (1891–1966), distinguished his own experiments with urine from the search for kiestéine (Marshall 192–93). Nonetheless, those successful twentieth-century innovations built on earlier research. The arrival of reliable and, eventually, routine pregnancy testing widened the gulf between patient and practitioner, delivering a powerful epistemological tool to the medical profession. But that facility had to be imagined before it was made, and it was forged in the anxieties that writers like Montgomery betray and that researchers like Kane believed they could transcend.

Notes

¹ The audio file is a dramatized reading of a single sentence from a nineteenth-century textbook on pregnancy diagnosis. First, a female voice gives the source of the quotation. She says: ‘William Fetherstone Montgomery, Exposition of the Signs and Symptoms of Pregnancy (1837).’ Then, the quotation is read out by a male actor, as if in the voice of its author, William Fetherstone Montgomery, who was a forty-year-old male obstetrician from Dublin, Ireland.

² See, for example, the discussion of pregnancy in Smith’s The Principles of Forensic Medicine, esp. 480–94.

³ For further reading on this point see, for example Williams’s Unmarried Motherhood in the Metropolis, 1700-1850.

⁴ This transition can be seen across the revisions to Taylor’s Medical Jurisprudence, first published in 1836. Where the earlier editions bemoan mistakes commonly made by juries of matrons, in the twelfth edition from 1891 the authority has shifted to medical men and the juries of matrons described as a thing of the past (Taylor 525).

⁵ See the state of kiestéine research as described in Rigby’s A System of Midwifery (96–97).

Bibliography

Kane, Elisha Kent. “Experiments on Kiesteine, with Observations on Its Application to the Diagnosis of Pregnancy.” American Journal of the Medical Sciences 4 (July 1842): 13–38.

Marshall, Mark. “The Kyesteine Pellicle: An Early Biological Test for Pregnancy.” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 22 (1948): 178–95.

Montgomery, William Fetherstone. Exposition of the Signs and Symptoms of Pregnancy. London: Sherwood, Gilbert, & Piper, 1837. Wellcome Collection. Web. 13 January 2022.

Nelson's Northern Lancet and American Journal of Medical Jursiprudence. 1852. Google Books. Free to read. Web. 13 January 2022.

Rigby, Edward. A System of Midwifery. Philadelphia: Lea & Blanchard, 1841. Internet Archive, from a copy in the Cushing/Whitney Medical Library, Yale University. Web. 13 January 2022.

Smith, John Gordon. The Principles of Forensic Medicine: Systematically Arranged and Applied to British Practice. 2nd ed. London: T. & G. Underwood, 1824. Wellcome Collection. Web. 13 January 2022.

Taylor, Alfred Swaine. A Manual of Medical Jurisprudence. 12th ed. London: J. & A. Churchill, 1891. Wellcome Collection. Web. 13 January 2022.

Williams. Samantha. Unmarried Motherhood in the Metropolis, 1700–1850. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018.

Created 13 January 2022