Acknowledgements: Many thanks to Niamh Laboisse for her assistance and support, to Philip Ward-Jackson for assisting me in my inquiries, and to the Royal Collection, the Ville de Paris, the National Portrait Gallery and Marion Harris, New York for granting me reproduction rights. [Click on the images to enlarge them. Please see the bibliography at the end of Part IV for a list of all the works cited.]

The Peace Trophy of 1856

Hogg's diatribe would have been more in keeping with the huge Peace Trophy unveiled, together with the Scutari Monument, as the Crimean War Memorial was then called, on 9 May 1856 during the "Peace Fête" celebrating the end of the Crimean War at the Sydenham Crystal Palace.

Context and commission

Left: "Ratification du Traité de Paris du 30 Mars 1856," Paris, J. Noël & Fourmage, 1856. © Gallica BNF. Right: Advertisement in the Morning Chronicle, 3 May 1856. British Newspapers Archive.

The Treaty of Paris, concluded on 30 March 1856, was ratified on 28 April 1856 and peace was proclaimed the same day together with a Public Thanksgiving to be observed on 4 May. From 29 April, an amazing advertisement, shown on the right above, was published in the press” by the directors of the Crystal Palace announcing the unveiling of a facsimile of the Scutari Monument and of a "trophy emblematical of peace" designed for the Crystal Palace Company, both works by Baron Marochetti. The trophy however had certainly been commissioned earlier. Indeed, soon after the conclusion of the Treaty of Paris, the architectural historian James Fergusson, the Crystal Palace's general manager, announced on 1 April a "grand fête", in honour of the conclusion of peace, to be celebrated at the Crystal Palace on 9 April. Three days later he postponed it until the beginning of May.

In mid-April, the trophy was in preparation and could be seen in Marochetti's studio. The press announced his "large figure of Peace" as a "rather bold experiment": The bust and arms of this statue were to be gilded; "the rest of the body regarded as a lay-figure and clothed with velvet and silver." It was impossible to predict what would be the result of "such a novelty" (The Times, 16 April 1856: 10). A few days before its inauguration, The Critic published an interesting article entitled "Polychromy," the end of which, praising the bust of the Princess of Coorg (quoted above), announced the Peace Trophy in these terms:

The much-vexed question of polychromy as applied to statues is about to receive further illustration under the superintendence of Baron Marochetti. The experience hitherto made in the Crystal Palace have not been of a kind to produce conviction in the mind of those who are by habits and association wedded to the notion of colourless statues, as the perfection of the ideal. More than one cause exists for this failure, among which a prominent one is the dull opacity of the material – plaster – to which colours has been applied. The effect of transparent colours upon the surface of marble is something very different, and this experiment is about to be tried to some extent in Baron Marochetti's statue of Victory, which is announced to be exhibited in the Crystal Palace during the summer. It has been stated, indeed, that colour is to be used for the garments and accessories of the figure, and that the limbs are to be gilded. If this be the case, we can only suppose that it is done through caution, in order not to test too severely at first the faith of the worshippers of pure marble. [The Critic, 1 May 1856; emphasis added]

This paragraph dedicated to Marochetti's Peace Trophy is worth being quoted in full because, mistaking the material of the work (as well as its name), it nevertheless suggests one plausible reason for its failure (quoted in italics). The plaster's opacity must have emphasised the colour. It can be judged” by comparing the marble bust of the Princess to the plaster model, also painted:

Left to right:(a) William Bambridge (1820-1879), Bust of Princess Victoria Gouramma (1841-1864), albumen print, 1856(?), Royal Collection Trust, RCIN 2800761© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2018. (b) Marble bust of Princess Gouramma of Coorg” by Baron Marochetti, Royal Collection, Durbar Corridor, Osborne (click for more details). (c) Polychrome plaster model of the bust of Princess Gouramma of Coorg” by Baron Marochetti, Private collection [background digitally removed — JB].

Even if the colour of the marble has faded, as it probably has, its transparency contrasts with the opacity of the colour applied to the plaster, which, on the contrary, must have increased with time. The author of the article had just seen the marble bust, which explains his confusion about the material: "We have had an opportunity of seeing Baron Marochetti's beautiful portrait bust of the Princess of Coorg, coloured after life; and it appears to us that the success of the experiment fully justifies the principles for which we contend." The plaster model was also painted, which means that Marochetti had included colour in his conception of this portrait-bust from the very beginning. The Times and the Critic both underline the role played” by Marochetti as a forerunner in nineteenth-century polychromy.

Inauguration of the Peace Trophy

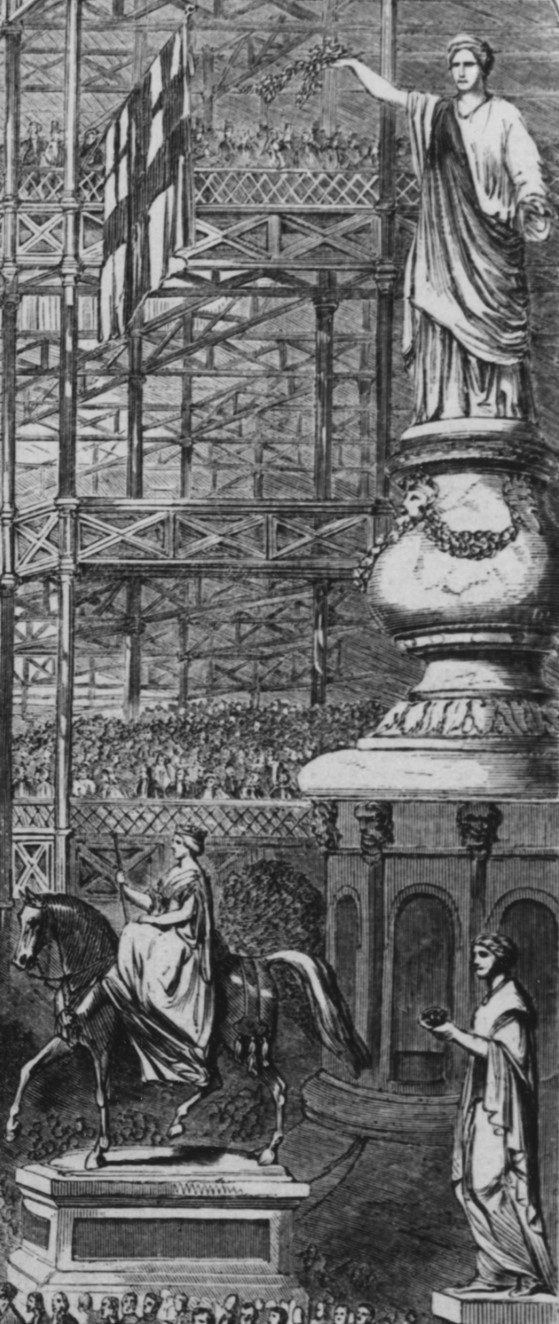

The Peace Fête at the Crystal Palace, on Friday, May 9, 1856, Illustrated Times, 17 May 1856: 344-5 © Philip Ward-Jackson.

The Peace Fête held at the Crystal Palace was Marochetti's most glorious day: four of his monumental works stood in the nave, on both sides of the Great Transept: on the south side, the Scutari Monument, and, opposite it, the Peace Trophy. In front of each of them were placed respectively plaster casts of the equestrian statues of Richard I, Coeur de Lion, the warrior king, an emblematic sculpture of the Great Exhibition of 1851 held at the former Crystal Palace, and of Queen Victoria (Glasgow, 1854), representing peace recovered in the United Kingdom. The main attraction was the inauguration of a full-size facsimile of the Scutari Monument, attended” by the Royal family and ...twelve thousand spectators. The imposing ceremony was detailed in the press, including the program of solemn music accompanying both unveilings.

In commissioning Marochetti to provide an emblematic figure of peace, the Crystal Palace's directors obviously wished to offer their visitors "a pleasing contrast" to the solemnity of the Scutari obelisk. This was most probably meant to be an ephemeral work of art designed for the purpose and destined to last only one season.

Description and reception of the Peace Trophy

This is not, however, what the artist and diarist Peter Orlando Hutchinson understood. Mistaking both monuments, he spoke of "the Baron Marochetti's model of his great statue of 'Peace,' designed to be erected at Scutari," adding: "It is a colossal female figure, holding a wreath of laurel. The flesh is gilt: the robe is silver: and an upper robe or scarf is also one mass of gilt. I infer that the statue will be the same" (10 May 1856).

In her journal (9 May 1856), Queen Victoria was categorical in her dislike of it:

The trophy consists of a colossal female figure holding in the right hand an olive branch, & in the left a sheaf of corn, representing peace and plenty. But this was a complete failure, looking unfinished and like the decoration of a cake [qtd. in Ward-Jackson, "Public and Private Aspects," n.10].

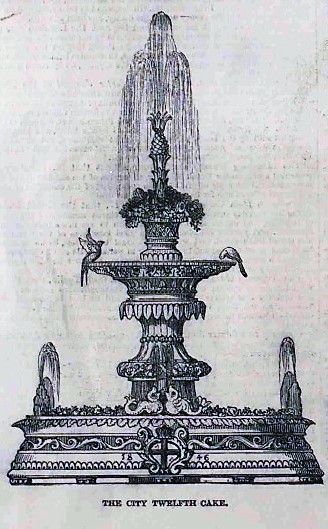

Several newspapers also derided the work for its similarity to a twelfth-cake ornament, as well as its profusion and variety of colours. In fact, the Peace Trophy unleashed a barrage of criticism.

Left: "The Peace Trophy, Detail of The Peace Fête at the Crystal Palace," Illustrated Times, 17 May 1856: 345 © Philip Ward-Jackson. Right: "The City Twelfth Cake," Illustrated London News, 3 January 1846: 12 © Illustrated London News Group.

To get an idea of what it looked, it is useful to compare newspapers' various descriptions with the two illustrations published of the inauguration. The emblematic figure of Peace was standing on a "raspberry ice coloured vase" supported” by a gigantic octagonal verd-antique pedestal, of about seventy feet in height, with empty niches. Around the base of the pedestal stood eight life-sized statues, silvered, gilt and bronzed. "Great credit is due to Mr Hayes, for the very able and remarkably rapid manner in which these colossal works were completed” by him, under the superintendence of Baron Marochetti" (Morning Advertiser, 10 May 1856: 5). A letter from Marochetti to Hayes (29 April 1856) gives accurate information about the gilding:

When you are ready to make an experiment in gilding a statue, I will be very glad to be there. It requires no more than a sufficient quantity of gold size to cover the statue with a slight wax, and powder to fix on it before it dries. I send to you the specimens I have received.... I made choice of the cheapest qualities when there were two of the same colour. I think that will do just as well.

Marochetti, who could not go to the palace that morning, added that his own men were going there to put up the statues. The result appeared unsatisfactory: "The figures, intended to fill the niches, were below, which quite spoiled the effect," remarked the Queen (qtd. in Ward-Jackson, "Public and Private Aspects..."). They are not visible on the illustrations of the inauguration but were described as celebrated statues of the Early Italian school. The top of the pedestal was decorated with heads. The critics gave no information about the material which this "heavy looking" pedestal "of great solidity" was made of. The whole trophy reached a height of one hundred feet, that is, the height of the Scutari Monument.

Such was the description of the colossal statue, twenty feet in height, in a letter to the Editor of the Daily News of 14 May 1856: "There is an antique-looking head with sightless eyeballs, a face and arms of stone, a real olive branch just torn from the tree in one hand, some equally real wheat in the other; new gold and silver tissue drapery covering the body...." There are unfortunately no further indications concerning its material. This statue of Peace was generally better received: "As a statue it is not without merit", conceded the critic of the same journal in his ferocious article (12 May 1856). However, others included it in their virulent criticism of the whole work: "The frightful appearance of this statue, that of a stout female in a white bedgown, with a yellow blanket thrown over her shoulders, will, we should think, settle for ever the question of colour applied to sculpture" (Morning Chronicle, 10 May 1856: 5).

Criticism of the Peace Trophy's polychromy

Proponents of colourless sculpture inevitably considered the Peace Trophy as provocative and offensive. A critic in the London Evening Standard of 14 July 1856 deplored "a profuse application of no less than eleven distinct colours" to the base and pedestal of the trophy (1). Two weeks later, on 28 July, the critic reported that Marochetti's peace trophy was completed:

The upper wreath of laurels has been silvered and spattered with gilt, and the lower wreath bronzed and spattered with silver.... Though dyed with as many colours as the rainbow, it is not brilliant; though ponderous, it is not impressive; and its loftiness only renders it more offensive to the eye. [1]

This was the commentator who had previously noted in the same newspaper, on 13 May 1856, that "Marochetti has given the rein to his rampant fancy for paint and gilding," and had felt that the Scutari monument's "simplicity is infinitely better than the 'Owen Jonesism' of decoration into which Marochetti has latterly fallen." In that commentary he had added, "the patches of red, gold, and green are so utterly whimsical and bizarre in effect, that the whole mass is as painful to the eyes as to the taste," and concluded:

We are quite aware of all the learned authorities which Marochetti and Owen Jones are prepared to quote as affording collateral or presumptive proof that the Greek always painted their statues; we know that the latter gentleman upholds that the frieze of the Parthenon was painted and gilded, and that he actually did the same with the restoration of the frieze at the Crystal Palace, till some more potent and tasteful authority whitewashed it over before the monstrosity was exhibited to the public (4).

In this extract, two comparisons catch our attention. One was between Marochetti and Owen Jones, whose famous Grammar of Ornament was being published that year and who had exhibited painted casts of the Parthenon frieze at the Crystal Palace two years before: both men are blamed for the central issue, of importing colour into sculpture and architecture. The other comparison, or rather contrast, is between the Scutari Monument and the Peace Trophy. It is very likely that Marochetti deliberately meant to offer with the latter a total contrast to the severity of his funerary obelisk: a glittering and joyful representation of Peace together with a claim for colour in sculpture.

Interpretation of the Trophy

Inauguration of the Peace Trophy and the Scutari Monument at the Crystal Palace, Illustrated London News, 17 May 1856: 524. Private collection.

In Marochetti's "trophy" there is not a single feature which is not offensive to good taste, excepting the head of the goddess, and that is a cast from the antique head of Juno which stands on the left hand as the visitor enters the Egyptian Court. Of course, Marochetti says nothing about where he got this head – the redeeming point of his trophy – and few are likely to recognise the theft under the coating of Dutch metal” by which it is concealed. [London Evening Standard, 28 July 1856: 1]

This comment is of major importance to understanding what Marochetti really intended to do. With his colossal statue of Peace, the head of which was a plaster cast of an antique head of Juno, Marochetti most probably meant to allude and pay tribute to Quatremère de Quincy's research on polychromy, published in his famous Jupiter Olympien. The trophy seemed to illustrate a text in which the author, speaking of devotion mannequins, draped with real cloth (Quatremère 10), was referring to Pausanias: "It is impossible to learn of what wood or metal the image is made.... Only the face and the hands and feet of the image are visible, for a white woollen shirt and a mantle are thrown over it" (Pausanias 87-88). The whole female figure was inspired” by the colossal chryselephantine Parthenon Minerva by Phidias, which Quatremère de Quincy had restored. The Minerva of the French sculptor Pierre-Charles Simart exhibited in 1855 in Paris, about which a long essay had just been published (see Beulé), could have reminded Marochetti of Quatremère's beautiful drawing.

From left to right: (a) Minerve du Parthénon, Pl. VIII, in Quatremère de Quincy, Le Jupiter Olympien, 1815 © Gallica BNF. (b) Colossal head of Juno Ludovisi, Rome, Palazzo Altemps. Source: Wikimedia Commons [background digitally removed — JB]. (c) French devotional figure, walnut, pine, and painted gesso, 32cm, c.1750 © Marion Harris, New York.

Wearing a chiton and a peplos, like the goddess, Marochetti's figure of Peace stood in the same position, her right arm raised, the left one extended downwards. Although there was no accurate mention of the statue's material in the newspapers, its arms must have been partly made from plaster. The head was almost certainly a plaster cast from the colossal head of Juno displayed at that time at the Crystal Palace: the Juno Ludovisi (Scharf 67, qtd. in Nichols 264).

As for the body, entirely clothed, it was, as suggested” by the critic in the Times, a type of lay figure, consisting of a wood or metal structure with jointed arms, the left one being covered” by a long sleeve. The feet of the statue were not visible, which allowed Marochetti to use a very simple, straight structure for the body, as shown in the illustration of the eighteenth-century devotional figure. The real olive branch and sheaf of corn strengthen the hypothesis that this was only intended to be an ephemeral work.

The gigantic Peace Trophy "gaily painted in gold and white," alluding to chryselephantine colossal statuary, was not a work of art in itself. It can be interpreted in two ways: as an idol emblematic of Peace to be admired” by the Crystal Palace's general public; and as a manifesto for polychrome sculpture intended for a well-informed audience. Unfortunately, it was received as a farce:

The model of the Scutari Monument is all very well in its way.... it certainly gives an excellent idea of what will some day be a very superb work of art. But the so-called Peace Trophy is execrable. Nothing could be more unlike MAROCHETTI the author of the Scutari Monument and the Coeur de Lion, than MAROCHETTI the perpetrator of this ridiculous gewgaw. [The Critic, 15 May 1856] 236]

Sir John Tenniel (1820-1914), Inauguration of the Scutari Monument and the Peace Trophy at the Crystal Palace, Sydenham, 9 May 1856, watercolour with white bodycolour, 47.7 x 33.6 cm, Royal Collection Trust, RCIN 916788 © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2018.

This watercolour depicts in fact the unveiling of the Scutari Monument, in front of which can be seen the plaster-cast of the equestrian statue of Richard Cœur de Lion.

The Trophy considered a failure

As can be seen from the above extract, not only Marochetti's detractors, but also those who acknowledged his talent rejected the trophy, among them William Michael Rossetti:

The Peace Trophy is, as a general design, about the most monstrous pasticcio of Renaissance commonplaces, flimsinesses, and abortive protuberances of forms which I remember to have been afflicted” by. How such an artist as Marochetti can tolerate a baseness of this kind, passes my comprehension. The wreath-holding giant figure of Peace, however, which surmounts it, in silvered and gilded drapery, and metallic flesh-hues, is an imposing work of effect, done for effect, and, as such, equal to the purpose [The Crayon, Vol.3, No.7, July 1856: 21; emphasis added].

W. M. Rossetti's comment (quoted in italics) gives a key to understand the Peace Trophy and its failure. The statue itself is not in question: "done for effect," it was indeed impressive, and this was certainly what Marochetti wanted. The main problem must have been the size of the huge pedestal and the way the different items were superposed. The fact that Marochetti completed his work during the following summer suggests that he must have been aware of the Queen's opinion. The context of this commission had compelled Marochetti to work in great haste (even the day of the inauguration had not yet been fixed when Marochetti wrote to Hayes on 29 April).

In fact, the site of the inauguration made a symmetrical display necessary. To match the height of the Scutari Monument, the huge pedestal was needed. Had it been "rummaged out of the back warehouse of a broker's shop" (as suggested” by the "Letter to the Editor" quoted above)? Whatever its origin, its original colour had been changed and, with its gothic shape and Italian statues at its base, it must have been conceived as a tribute to mediaeval polychromy. However, it is hardly likely that in Marochetti's mind the pedestal formed part of the peace trophy from the very beginning, it was probably added afterwards and that is what ruined the effect, making it look like a twelfth-cake ornament! This assembling of disparate elements was far too heterogeneous: "The bottom portion rises perpendicularly; the next slopes upwards; then comes the perpendicular octagonal prism; then a projecting circle; then a nondescript support" (London Daily News, 12 May 1856: 2).

Two issues are particularly significant here. First, how had Marochetti not anticipated the critics' reaction? He probably had. But, being at the peak of his fame in 1856, he could take risks and thought his project would be worth it. Moreover, he certainly relied on an insightful comment. Unfortunately, he was misunderstood. Secondly, why had this tribute to polychromy not been decoded? Marochetti was referring to Quatremère de Quincy. Remarkably, the Jupiter Olympien has never been translated into English. John Flaxman, Quatremère's exact contemporary, was aware of the "elaborate work" of the French author (Flaxman 185). But it is doubtful that, forty years later, despite the contribution of Charles Knight's Pictorial Gallery (1847), British critics looking at Marochetti's Peace Trophy, could have in mind the beautiful restitution of Minerva” by Quatremère de Quincy.

The removal of the trophy

On Saturday 20 September 1856, another fête was held at the Crystal Palace providing various amusements:

There was also a further attraction in the interior of the palace, ... we mean, of course, Marochetti's peace trophy, which has been in course of demolition for the last week, and is now completely removed. We most sincerely congratulate the directors on having taken this step, and carted away an obstruction which disfigured the whole building. How they will answer to the shareholders for having expended, if we are rightly informed, nearly 5000£ upon it, is quite another matter. [London Evening Standard, 22 September 1856: 3]

During the summer, animosity towards Marochetti had increased. Such a big commission as the Crimean War Memorial (the Scutari Monument) given to a foreign sculptor could not go unnoticed. At that time, Marochetti was also suspected of getting the commission of the Wellington monument to be erected in St Paul's cathedral, which led William Michael Rossetti to write of "the Marochetti crisis in British Sculpture art" (The Crayon, September 1856: 276).

To the gossip about the cost of the trophy, James Fergusson, the Crystal Palace's general manager, published a reply in the same newspaper one year later, giving a full report of the "arrangement" concluded with Marochetti concerning the Peace Fête:

The amount paid to the Baron Marochetti for the designs and drawings, and for his personal superintendence of the erection of the peace trophy and the other monuments erected for the festival, was the 100£ alluded to in the committee's report. The 650£ named was for the purchase of the colossal equestrian statues of Richard Cœur de Lion and of the Queen, and for the construction of the Scutari monument. All these monuments were cast, brought to the palace, and erected at the sole cost of Baron Marochetti,” by previous arrangement with him. The expense incurred” by him under these heads was so great that it is doubtful if, even including the 100£, he was not a positive loser” by his bargain with the company. It should be remembered that the two equestrian statues, with the four figures of the Scutari monument, remain the property of the company. [London Evening Standard, 10 August 1857: 6; emphasis added]

Fergusson was a friend of Austen Henry Layard, himself a good friend of Marochetti's (see Ward-Jackson 2017: 6). It is likely that these observations (qtd in italics) had been submitted at the sculptor's request.

Writing to a friend in 1854, Marochetti insisted on the great impression made on him” by the Elgin Marbles (Ward-Jackson, "Austen Henry Layard," 6). In 1856 his interest in polychromy was allowed free expression:” by creating the Peace Trophy, Marochetti showed how involved he was in the nineteenth-century debate about polychrome sculpture. A few years later, he again expressed his enthusiasm for Quatremère de Quincy in a work which received the assent of an opponent of polychromy, the well-known French art-historian Charles Blanc. The story of his experiments with polychromy was” by no means over.

Related Material

- Part I: The busts of Princess Gouramma of Coorg, Maharajah Duleep Singh, and Queen Victoria

- Part III: Queen Victoria as "Queen of Peace," and the Monument to Eliza Roy, Comtesse de Lariboisière

- Part IV: Polychromy and materials (with Conclusion and Bibliography)

- The Elgin Marbles, Polychromy, and Ancient Greek Art as an Aesthetic Ideal

- "The Colour of Anxiety: Race, Sexuality and Disorder in Victorian Sculpture" [review of the exhibition at the Henry Moore Institute, London (2022-23)]

Created 4 June 2018