The Royal Academy exhibition entitled "Modern British Sculpture" (January to April 2011) had mixed reviews. Two of the first three rooms were devoted to Edwin Lutyens (a rather too large model of the Cenotaph) and Jacob Epstein (Adam and photos of the BMA/Rhodesia House sculptures). The Victorian era was represented by just two works — Frederick Leighton’s Athlete Struggling with a Python (1877) and Alfred Gilbert’s Jubilee Memorial to Queen Victoria (1887). Henry Moore and Barbara Hepworth were given good coverage.

Thereafter the exhibition seemed to lose its way. One room was devoted entirely to ceramics and the later rooms had many items which did not appear to be either British (Gustav Metzger’s Page Three, a collection of 93 magazine covers of glamorous young ladies) or Sculpture (Hamish Fulton’s April 1967, a printed timetable showing hitchhiking times between London and Andorra).

The comprehensive 300 page catalogue contains some important essays relevant to those interested in Victorian sculpture. The first, "British British Sculpture Sculpture" [sic], is by Dr Penelope Curtis, Director of Tate Britain and co-curator of the exhibition. She describes Leighton’s Athlete and Gilbert’s Victoria as key works which mark a legacy that endured and refers to the "remarkable liveliness [of British sculptors] in the 1880s and 1890s (christened the “New Sculpture” by Edmund Gosse in 1894).

Alfred Drury's Joshua Reynolds gracing the courtyard of the Royal Academy.

Dr Curtis commends New Sculpture artists generally for their craftsmanship and innovation, but the only names she mentions are Thomas Brock and Alfred Drury whose statues of Thomas Gainsborough and Joshua Reynolds grace the main staircase and courtyard of the Royal Academy. In comparing these statues with Epstein’s Strand sculptures, she notes that they are "less controversial and even retardataire" — a polite word for "outmoded." In fairness to Brock (and by extension to Drury), the story of Gainsborough deserves to be told.

In 1899 a Mr. Henry Vaughan left £1000 for a statue of Thomas Gainsborough to be presented to the newly established Tate Gallery, now Tate Britain. Brock was given the commission and in 1906 the marble statue was duly installed in the Tate. By the 1920s it had been moved to a less prominent position and it was later put into storage (where it remains). In 1939 the Royal Academy received permission from the Tate to have a bronze replica made and it was placed in its present location. The statue can hardly be criticised for being retardataire in 1939 when it actually dated from 1906 and was well regarded at that time. As the context makes clear, it was the views of the Royal Academy Council that were outmoded, not the statue.

Lord Leighton's Athlete.

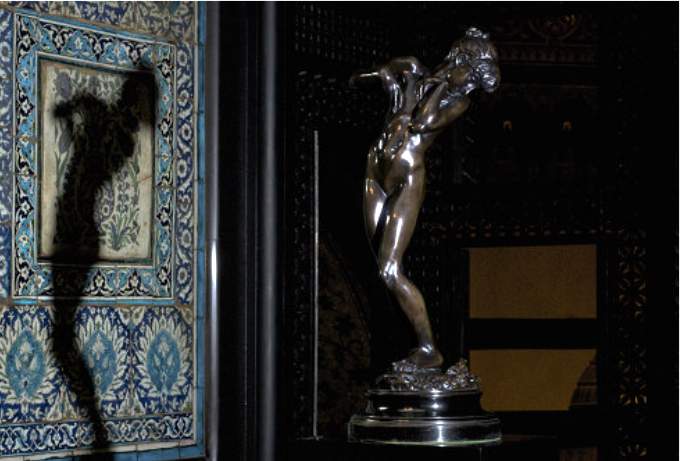

In the exhibition, Leighton’s Athlete and Gilbert’s Queen Victoria were juxtaposed with Charles Wheeler’s Adam and Philip King’s Genghis Khan. To quote the catalogue: "A seated figure of a queen-empress is flanked by three sculptures of idealised males . . . taken together they examine the relationship between statuary and sculpture, and between the figure and the monument." In her essay, "Authority Figures," Martina Droth makes a brave attempt to justify the "strange configuration" by pointing out that two of the works are male nudes, three are bronzes and all four were sculpted by Academicians. They still make an odd quartet.

Dr. Droth notes that Lord Leighton set a new benchmark for sculptors and recognised that Academy membership "not only conferred status but also visibility." However she seems somewhat baffled by the Athlete; she calls it "stylised and overworked" and adds "we might easily walk right past it; as a solitary figure, it appears at once odd and generic, and it is difficult to know what to make of it." Do I hear the noble lord turning in his tomb?

Left two: Lord Leighton's and The Sluggard and right two: Needless Alarms.

She is also wide of the mark when she suggests that Alfred Gilbert was "an assistant to Leighton, in all senses of the word" [my italics]. It is true that many were surprised when, at his first attempt at sculpture, Leighton produced so finished a work as the Athlete. It was hinted that he must have had some help and it was known that the Athlete was modelled in Thomas Brock’s studio. Leighton himself confirmed in the Belt v. Lawes case (1882) that he had made use of Brock’s expertise in bronze work, although the artistic individuality of the work was wholly his own; and he defied the critics by modelling his last two bronzes — The Sluggard and Needless Alarms — in Brock’s studio.

In her note on the Athlete for the 2001Tate exhibition, Exposed — the Victorian Nude, Dr. Alison Smith wrote that “Leighton was assisted” by his protégéé Thomas Brock" (p.238) and she described The Sluggard as "the second of two life-sized bronzes made by Leighton in collaboration with the sculptor Thomas Brock" (p.116). Moreover, the broken statuette shown in the photo of Gilbert’s studio bears little resemblance to Needless Alarms. Gilbert enjoyed Leighton’s patronage and friendship; but he did not assist him with his sculptures. That was Brock’s privilege.

Droth rightly praises Gilbert’s Queen Victoria. However, it has to be pointed out that it was not particularly successful as a public monument. The catalogue note reminds us that the elaborate bronze canopy over the royal head fell down within a few months (as gleefully caricatured by Punch) and the statue itself had to be moved indoors to a less conspicuous site in Winchester. Perhaps a monument should be judged not just by its decorative fantasies but also by its durability and fitness for purpose.

This leads us to the catalogue’s rather unexpected Appendix I, "The Dissemination of Commemorative Statues of Queen Victoria" — unexpected because such statues are not normally classified as "Modern British Sculpture." The excuse (or link) is of course Gilbert’s Queen Victoria and the influence this imaginative work had on the 130 or so statues of the Queen commissioned and installed after 1887. Jennifer Powell’s intriguing study presents much valuable (if rather selective) material on the nature, type and location of these statues and also gives a more balanced view of the influence of Gilbert. She notes that "it would be inaccurate to suggest that the general usage of the seated figure was a direct result of Gilbert’s example"; she might have added that the increase in the use of bronze simply reflected the fact that the metal, particularly in Britain, was less subject to the ravages of fog and grime than marble.

Left to right: (a) Three views of Brock's famous Victoria Memorial at the end of the Mall and (b) a detail of Brock's statue of the Queen at Hove, showing Victory on her orb.

The image of Victory on an orb had been used by Canova in his Napoleon as Mars the Peacemaker (1806), but Gilbert’s adoption of the device as a symbol of Victoria’s imperial rule was certainly an influence on subsequent representations of the Queen. For example, Brock used it to decorate the orbs of five (Hove, Carlisle, Brisbane, Cawnpore and Lucknow) of his thirteen statues of the Queen — although not for the Victoria Memorial in front of Buckingham Palace, which Dr. Powell strangely omits to mention. Brock intended the Memorial to reflect the best features of British sculpture during Victoria’s reign, and he paid tribute to Gilbert by depicting a seated Queen and by crowning the apex of the monument with a massive gilded Victory. However, the orb was decorated with a figure of Saint George and the Dragon.

In his Foreword to the catalogue the President of the Royal Academy explains that the exhibition was not intended to answer the questions "What is sculpture?" and "What is British?", but rather to "open a debate." The debate will continue for some time. Meanwhile, those who saw the exhibition and were baffled by it — and those who did not see it and wondered what they had missed — will find this catalogue a good investment at £9.95.

Bibliography

Curtis, Penelope, and Keith Wilson, eds. Modern British Sculpture. London: Royal Academy of Arts, 2011. 316pp (pbk £9.95, ISBN 978-1-905711-72-7; hbk £40, ISBN 978-1905711-73-4).