[Click on images to enlarge them. Unless otherwise noted, all photographs come from the exhibition press release or catalogue. Thanks to Sara Chan, Assistant Press Officer, Tate Britain, for providing many of the images of works in the exhibition.]

Anyone contemplating a definitive exhibition of Victorian sculpture, such as the organizers seem to have done, immediately faces the major problem that so much important Victorian work can't be brought into an exhibition space.

Left: The Albert Memorial designed by Sir George Gilbert Scott with work by sculptors including John Henry Foley, William Calder Marshall, and William Armstead. Middle: Sir Thoma Brock's Victoria Memorial. Right: Sir W. Hamo Thornycroft's Gladstone Memorial. [Photographs by the author]

After all, much of the greatest Victorian sculpture appears in the form of major outdoor monuments, such as the Albert Memorial, Brock's Victoria Memorial, and Thornycroft's Gladstone Memorial near the Law Courts. Second, a great quantity of Victorian work carved into stone or cast in bronze appears in churches and cemeteries. Finally, a great portion of Victorian sculture appears on the facades and interiors of buildings, such as the Foreign and Colonial office, the Chartered Accountant's building, and Lloyds (see below).

Left: Britannia and her companions on the Foreign Office by Henry Hugh Armstead and J. Birnie Philip. Middle: Institute for Chartered Accountants Building. John Belcher, architect. Right: Sculpture on the North Turret on Lloyd’s Register of Shipping by Sir George Frampton. Architect: T. E. Collcutt [Photographs by author and Robert Freidus]

So what is an organizer to do? One approach involves obtaining photographs, drawings, or maquettes of the larger unobtainable work, and this the organizers have tried to do in presenting Alfred Stevens’s Wellington Monument in St. Paul's Cathedral but without much success in either venue. (Both sorely needed the V & A's giant versions of Valor and Cowardice and Truth and Falsehood along with the V & A's large wooden model of the monument.) Another approach is to admit that one can't include such works and concentrate on the most beautiful or important objects available. In the case of Victorian sculpture, this requires an emphasis on the often exquisite exemplars of the cult of the statuette” by Brock, Thornycroft, Frampton, and so many others. This, surprisingly, the organizers of Sculture Victorious have not done. Instead they have emphasized a range of important themes that they apparently believed would adequately compensate for the lack of these objects, or perhaps they didn't understand the centrality of such work, and this lack has prompted much of the severe criticism the exhibition has received. Conspicuously absent are E. H. Baily, Sir Joseph Edgar Boehm, Thomas Brock, Aimé-Jules Dalou, William Goscombe John, Sir Edgar Bertram Mackennal, William Calder Marshall, Matthew Noble, Frederick W. Pomeroy, Francis Derwent Wood, Thomas Woolner, and a host of others. Given the absence of so many major figures, some of the works included, such as the bas relief triptych by Mary Seton Watts, certainly seem surprising. With so many women sculptors from Mary Thornycroft and Lady Feodora Gleichen to Margaret Giles at work during the age of Victoria, why include a work based on her husband's painting?

Since I first reviewed the exhibition in New Haven, I have had the opportunity to see the Tate version and discuss both versions with a number of people long involved in collecting, exhibiting, and writing about Victorian sculpture. Some of what follows depends heavily on their opinions and suggestions, one of which that strikes me as convincing is that the organizers would have done far better to have entitled the show "Victorian Technology and Sculpture," since this is an important subject that the show manages to introduce, if not thoroughly examine. Another attractive suggestion involved mounting it at the Victorian and Albert Museum, which, unlike the Tate, has long shown its Victorian sculpture and as already mentioned possesses certain objects that obviously belong in here.

For me, the single most important function and effect of any exhibition is bringing together in a single space works that the viewers either will have not seen or will not have not seen in proximity, and despite any other criticisms one might make of the show, we should praise the organizers for creating an exhibition with some magnificent, sometimes little-known, work, such as the William Reynolds-Stevens A Royal Game. Unfortunately at times the desire to include large and unexpected objects seems, at least in the opinion of many of those with whom I spoken, to have led the organizers astray.

Left: The Minton Elephant with the Giant Peacock seen behind. Thomas Longmore created the elephant (1889 © Thomas Goode & Co. Ltd., London, and Paul Comolera created the peacock, which was manufactured by Minton & Co. (1873 © National Museums Liverpool, Walker Art Gallery). Both are lead and tin-glazed earthenware (majolica) Right: The elephant appearing on banner for the show. [Photograph at right by the author]

For example, the enormous Minton brightly colored elephant certainly meets the requirements of a magnificent, large-scale, technically masterful object, but the question — the Elephant in the Room — remains, with all the magnificent bronzes omitted from the show, why except for the elements of novelty and "We can get it!" is it here? In New Haven the inclusion or role of the elephant seemed particularly problematic for two reasons, the first of which is that it dominated the poster for the show, which suggested that it was not going to be about what most people thought Victorian sculture to be at all. Whether one thinks the organizers had made a bold attempt to broaden our expectations or simply didn't have an adequate understanding of the exhibition, the problem remains that they placed the Minton elephant at the entrance to the building a good distance from the show on the floor above and most people seem to have have just passed it by. Someone who attended Sculture Victorious with me thought that this object was part of the permanent collection and had nothing to do with the show. The Tate avoided this second problem by placing the elephant in a room containing a miscellany of objects displayed at international exhibitions, though, as Richard Dorment has charged, putting this giant ceramic elephant in the same exhibition space as two statues of enslaved women and leather carvings that simulated wooden simulations of lobsters and game created quite a few difficulties, too.

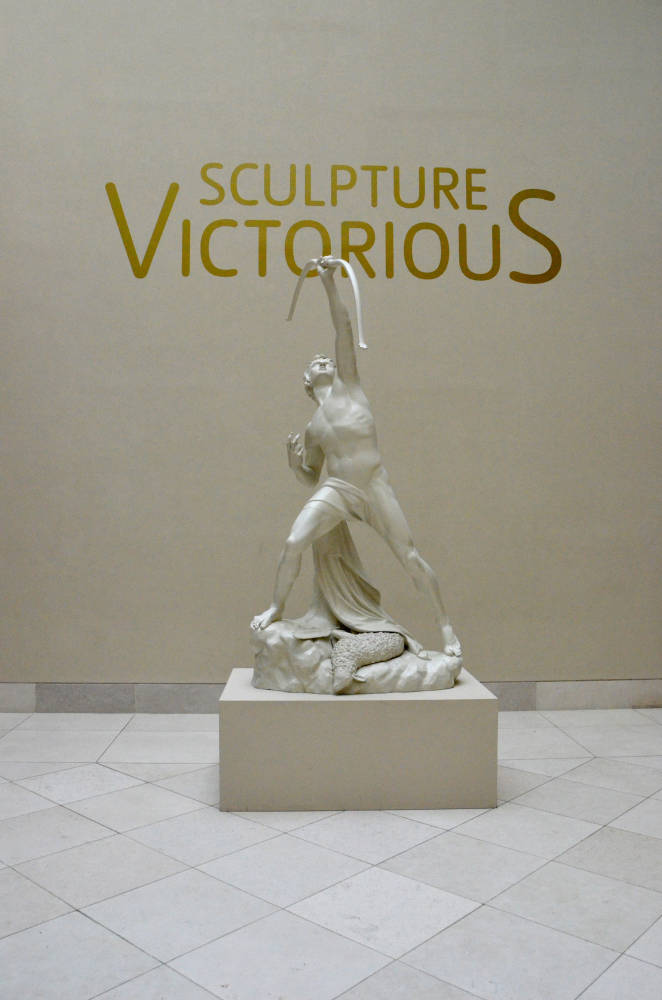

Encountering what is purportedly the same exhibition mounted in two different museums emphasizes the strengths and weaknesses, successes and failures, of the approaches taken in each venue. Such is certainly true of the two incarnations of Sculpture Victorious, which first opened at Yale University's Center for British Art and them moved to Tate Britain. The Tate had far more room to display the objects, and its version of Sculpture Victorious had the major advantage of including several major works, such as Thornycroft's Teucer and Leighton's Athlete Struggling with a Python that did not travel across the Atlantic.

Works shown at the Tate but not at Yale. Left: Teucer by Sir Hamo Thornycroft. 1881. Bronze. Middle: Athlete Wrestling with Python by Sir Frederic Leighton. 1877. Bronze. Presented by the Trustees of the Chantrey Bequest 1911. Right: Hero and Leander by Henry Hugh Armstead. c. 1875 Marble. Bequeathed by the artist 1906. All three © Tate Britain. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

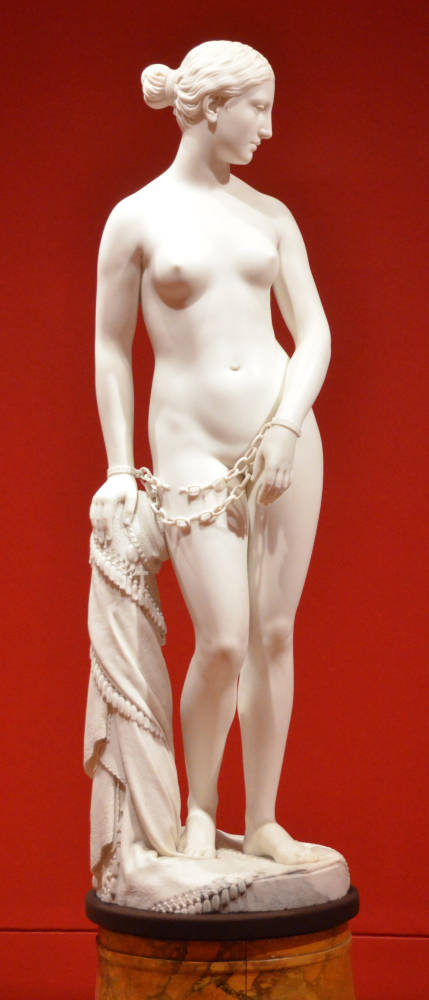

Works shown at the Tate but not at Yale (II). Left: The Greek Slave by Hiram Powers. 1844. Marble. ©The Rt. Hon. Lord Barnard T.D., Raby Castle, Co. Durham. Yale had a later copy of this work. Middle left: Model for 'Eros' on the Shaftesbury Memorial, Piccadilly Circus. Alfred Gilbert. 1891, cast 1921 Bronze on marble base. 730 x 278 x 670 mm. © Tate Britain. Middle right: Veiled Vestal by Raffaelle Monti. 1847. Carrara marble. © Trustees of the Chatsworth Settlement. Right: A Bronze Reduction of the Laocoon by Ferdinand Barbedienne. 1854. Bronze. Royal Collection Trust. © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2015. © Tate Britain. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

The Tate show certainly began well when it placed John Bell's 1851 Eagle Slayer in painted iron (!) immediately outside the entrance, and it also included a good touchscreen presentation of the many monuments commemorating Queen Victoria's Jubilee. The Tate would therefore seem to have all the advantages on its side, and it certainly did some things better. Two works in particular showed to better advantage than they had New Haven: The Yale designers had raised William Reynolds-Stephens’s magnificent A Royal Game on a plinth to emphasize its importance, but the Tate's placement of the work directly on the floor and in brighter light proved much kinder to the work, in large part because it made the chess game much easier to see. Similarly, Westmacott's Baron Saher de Quency, which essentially opened the Yale show, emphasizing both the political and technological aspects of Victorian sculpture, looked far better — had more “pop” — in the Tate's brightly lit, red-walled room, though, true, there it lost much of its intended significance. That Minton Elephant, now in proximity to a giant peacock, also looked much better at the Tate. But not all works came off better at the Tate. For example, both George Frampton's multi-media Dame Alice Owen and Reynolds-Stephens’s Happy in Beauty Life and Love and Everything stood out more in Yale's lower light levels. My observations about the different ways the some objects appear in different mountings of this exhibition show, not that either designers necessarily did anything wrong but that lighting and wall color of the exhibition space have crucial effects on the viewer’s pleasure and perception of individual objects.

Two rooms at the exhibition, the one at left containing objects not present at the initial mounting of the exhibition in New Haven. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Surprising as it might seem, given all the major advantages of the Tate version, — particularly the addition of several major works and the far larger exhibition space — the Yale version proved more successful. Although it certainly omitted much of what most of us working with Victorian sculpture wanted included, even emphasized, it did make its points about the political and technological valences of Victorian work in stone and bronze far more effectively than did the Tate. When I found obvious works missing from the New Haven show, my first thought was why did the organizers choose to devote their scarce wall and floor space to, say, American works, such as The Greek Slave by Hiram Powers or Zenobia in Chains by Harriet Hosmer plus numerous objects referring to it — prints, daguerreotypes, and a large hideous table-cloth-sized bit of fabric. When I found works missing fron the Tate's large, almost empty rooms, I wondered why they hadn't included works from their own collection, such as Thornycroft's Mower or more crucial to an exhibition supposedly emphasizing the role of technological experimentation in the sculpture of this period, why not include John Harvard Thomas's Lycidas, on which David Getsy's Body Doubles lavished such attention?

Why not these? Right two: John Harvard Thomas's Lycidas. Left: Hamo Thornycroft's .The Mower. This is not the Tate cast.

In short, despite whatever shortcomings both versions of the show may have had, they did succeed in exhibiting some magnificent work, and they did make at least some attempt to emphasize the political, economic, and technological contexts of work in stone, bronze, and other mediums, such as glass, Parian ware, and silver. The show I saw at Yale's British Art Center, however, seemed to have a much sharper focus than the one at the Tate. I may not have agreed entirely with the approach taken by the New Haven organizers, but I understand what they had tried to accomplish. Despite some signal successes, the Tate version of Sculpture Victorious, in contrast, seems to lack vision, focus, and quite a few works of sculptural art. George Bernard Shaw famously described the England and America as two nations separated by a common ocean and a common language. That's the kind of gap that seemed to have opened between the Yale and Tate versions of Sculpture Victorious.

Related material

- Amazing objects: A review of Sculpture Victorious: Art in the Age of Invention, 1837-1901

- “These polemical, metasculptural objects” — a review of David J. Getsy's Body Doubles: Sculpture in Britain, 1877-1905

Other reviews of the exhibition

Dorment, Richard. [Review.] The Telegraph (February 23, 2015). Web version.

By using works of art to illustrate what amounts to an extended academic lecture, the curators end up with a show that’s deadly dull from start to finish by the end, we’ve learned very little about what actually happened in 19th century British sculpture, but a great deal about the loss of direction the discipline of art history has experienced in recent years.

Duguid, Lindsay. “Stiffly Fanciful.” Times Literary Supplement (April 17, 2015): 18.

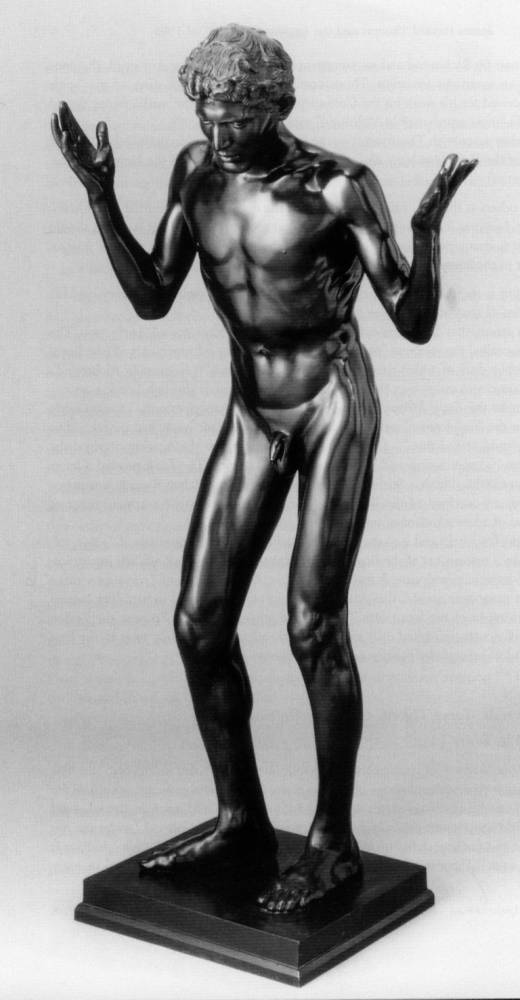

The break between public display snd private appreciation, figured in the few examples on display of what Edmund Gosse termed the New Sculpture, is rather passed over, It was, however, well illustrated in the small recent exhibition at the Fine Art Society, where bronze statues of Thornycroft’s “The Mower, Gilbert’s “Perseus Arming,” and Leighton’s “The Sluggard” were displayed in an appropriately connoisseurial setting. Having been impressed at the Tate” by public grandiosity, the visitor to the Fine Art Society could look closely at the foot-high bronzes, noting the fine details of ribcage, neck tendons, and buttocks, reproduced using the “lost wax” method of cast making to aesthetic rather than epic effect. The delicacy of the modelling, the feeling of suppressed sexuality and decorative effect make these pieces more intelligible to the modern eye than the large pompous exhibition items at Sculpture Victorious.

Bibliography

Sculpture Victorious: Art in the Age of Invention, 1837-1901. Eds. Martina Droth, Jason Edwards, Michael Hatt. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2014.

Last modified 21 May 2015