Photographs and captions by Jacqueline Banerjee, who also downloaded the woodcut illustrations from Smiles's biography, which Smiles tells us were "from sketches made on the spot by Mr. Edward Whymper" (vi). Omissions and an interpolated summary are marked by square brackets. You may use all the images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer or source and (2) link your document to this URL or cite the Victorian Web in a print one. [Click on the pictures to enlarge them.]

George Stephenson. Source: Smiles, frontispiece.

The village of Wylam, like most other colliery villages, consists of an unsightly pumping engine surrounded by heaps of ashes, coal dust, and slag; an iron-furnace, smoking and blazing by night and day; and a collection of labourers' dwellings of a very humble order. The place is more remarkable for the amount of its population than for its cleanness or neatness as a village — the houses, as in all colliery villages, being the property of the owners or lessees, who employ them for the temporary purpose of accommodating the workpeople, against whose earnings there is a weekly set-off of so much for house and coals. This village of Wylam would be altogether uninteresting but for the fact that in its immediate neighbourhood Avas born one of the most remarkable men of this century — George Stephenson, the Railway Engineer.

High Street House, George Stephenson's birthplace near Wylam, Northumberland: "a small, typical Northumbrian C18 house with horizontal sash windows and a horizontal boarded door" with "[s]teeply pitched roof pantile roof, edged in stone slates" (Grundy et al. 637).

His father, Robert Stephenson, or "Old Bob," as the neighbours termed him, worked for several years as engineman at the Wylam Pit. The old pumping engine has long since been pulled down; but the house still stands in which Robert Stephenson lived, and in which his son George was born. It is situated a few hundred yards from the eastern extremity of the village, and is known by the name of High Street House. It is a common two storied, red-tiled, rubble house, portioned off into four labourers' compartments. It served the same use then which it does still — that of an ordinary labourer's dwelling, its walls are still unplastered, its floor is of clay, and the bare rafters are exposed over head.

The lower room on the west end of this cottage was for some years the home of the Stephenson family; and there George Stephenson was born on the 9th of June, 1781, as appears from the record in the family Bible, which is still preserved. [...]

Left: Plaque on the cottage wall. Right: St Mary's, Ovingham, Northumberland, the Grade I listed church (restored in 1857) church where Stephenson's maternal grandparents were buried.

Robert Stephenson had lived and worked at Walbottle, a village situated about midway between Wylam and Newcastle, during the earlier part of his life; and he removed from thence to Wylam as engineman. A tradition is preserved in the family, that Robert Stephenson's father and mother came from beyond the Scottish Border, on the loss of considerable property, and a suit was even commenced for its recovery, but was dropped for want of the means to prosecute it. Certain it is, however, that Robert's position throughout life was that of a humble workman. His wife, Mabel Carr, was a native of Ovingham, the daughter of one Robert Carr, a dyer. The Carrs were, for several generations, the owners of a house in that village adjoining the churchyard; and the family tombstone may still be seen standing against the east end of the chancel of the parish church, underneath the centre lancet window; as the tombstone of Thomas Bewick, the wood-engraver, occupies the western gable.[...]

The earnings of old Robert were very small — they amounted to not more than twelve shillings a week; and as there was a growing family of six children to maintain, of whom George was the second, the family, during their stay at Wylam, were in very straitened circumstances. As an old neighbour said of them, "They had little to come and go upon; they were honest folk, but sore haudden doon in the world." The father's earnings being barely sufficient, even with the most rigid economy, for the sustenance of the family, there was little to spare for their clothing, and nothing for their schooling, so none of the children were sent to school.

Left: The old Post Road, running past the cottage, where "waggons ... were then dragged by horses ... immediately in front of the cottage door" (11). Right: The countryside around the cottage, where Stephenson learnt his love of nature — the River Tyne flowing close by.

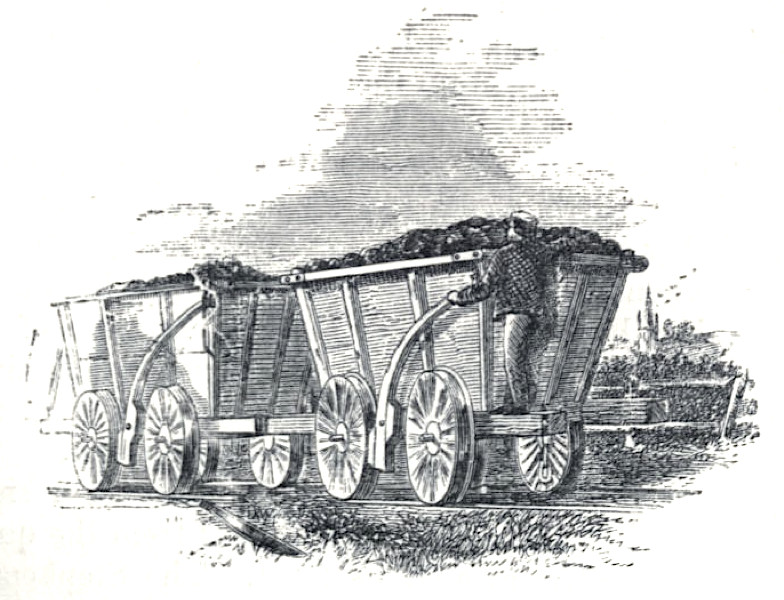

The boy George led the ordinary life of working people's children. He played about the doors; went birdnesting when he could; and ran errands to the village. He was also an eager listener, with the other children, to his father's curious tales; and he early imbibed from him that affection for birds and animals which continued throughout his life. In course of time he was promoted to the office of carrying his father's dinner to him while at work, and it was on such occasions his great delight to see the little robins fed. At home he helped to nurse, and that with a careful hand, his younger brothers and sisters. One of his duties was to see that the younger children were kept out of the way of the chaldron waggons, which were then dragged by horses along the wooden tramroad immediately in front of the cottage door. This waggon-way was the first in the Northern district on which the experiment of a locomotive engine was tried. But at the time of which we speak, the locomotive had scarcely been dreamt of in England as a practicable working power; horses only were used to haul the coal; and one of the first sights with which the boy was familiar was the coal-waggons dragged by them along the wooden railway at Wylam.

Coal waggons. Source: Smiles 31.

Thus eight years passed; after which, the coal having been worked out on the north side, the old engine, which had grown "fearsome to look at," as an old workman described it, was pulled down; and then old Robert, having obtained employment at the Dewley Bum Colliery as a fireman of the engine, removed with his family to that place. Dewley Burn, at this day, consists of a few old-fashioned low-roofed cottages, standing on either side of a babbling little stream. They are connected by a rustic wooden bridge, which spans the rift in front of the doors. In the central one-roomed cottage of this group, on the right bank, Robert Stephenson lived for a time with his family. The pit at which he worked stood in the rear of the cottages. The coal has long since been worked out, and the pit closed in; and only the marks of it are now visible, a sort of blasted grass covering, but scarcely concealing, the scoriae and coal-dust accumulated about the mouth of the old pit. Looking across the fields, one can still discern the marks of the former waggon-way, leading in the direction of Walbottle. It was joined on its course by another waggon-road leading from the direction of Black Callerton. Indeed, there is scarcely a field in the neighbourhood that does not exhibit traces of the workings of former pits.

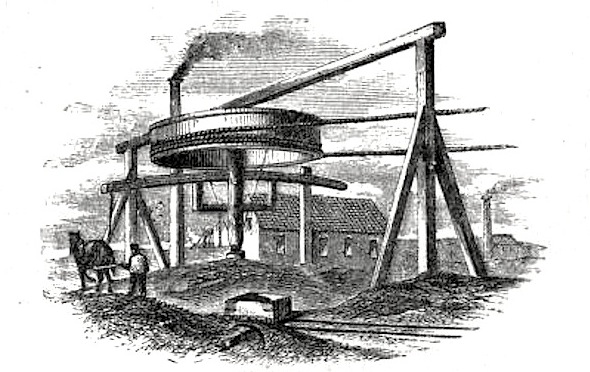

The Colliery Gin. Source: Smiles 14.

As every child in a poor man's house is a burden until his little hands can be turned to profitable account and made to earn money towards supplying the indispensable wants of the family, George Stephenson was put to work as soon as an opportunity of employment presented itself. [Starting with simple jobs like cow-herding, ploughing and hoeing, Stephenson joined his elder brother James and father in the mines, rising from coal-picking to driving the gin horse, becoming an assistant fireman to his father, and by stages achieving his ambition to become an engineman. Although the family had moved by then, this was at a new pit between the Wylam waggon road and the Tyne. He was still only eighteen.]

But from the time when George Stephenson was appointed fireman, and more particularly afterwards as engineman, he applied himself so assiduously and so successfully to the study of the engine and its gearing, — taking the machine to pieces in his leisure hours for the purpose of cleaning and mastering its various parts, — that he soon acquired a thorough practical knowledge of its construction and mode of working, and thus he very rarely needed to call to his aid the engineer of the colliery. His engine became a sort of pet with him, and he was never wearied of watching and inspecting it with devoted admiration. [...] While studying to master the details of his engine, to know its weaknesses, and to quicken its powers, George Stephenson gradually acquired the character of a clever and improving workman. Whatever he was set to do, that he endeavoured to do well and thoroughly; never neglecting small matters, but aiming at being a complete workman at all points; thus gradually perfecting his own mechanical capacity, and securing at the same time the respect of his fellow workmen and the increased confidence and esteem of his employers. [Smiles 8-20]

Sources

Grundy et al. The Buildings of England: Northumberland. London: Penguin, 1992.

Smiles, Samuel. The Story of the Life of George Stephenson, Railway Engineer. Abridged ed. with Portraits and Illustrative Woodcuts. London: John Murray, 1859. Internet Archive. Uploaded by the University of Toronto. Web. 9 September 2014.

Last modified 9 September 2014