George Stephenson, by Thomas Lewis Atkinson, after John Lucas. Mixed-method engraving, published 1849. © National Portrait Gallery, with thanks. NPG D13734. [Click on all the pictures to enlarge them.]

George Stephenson (1781-1848), often termed the father of the railways, was born on the outskirts of Wylam, on the bank of the River Tyne in Northumberland. Wylam was then a mining village, dominated by its colliery, and during his early childhood the family lived in one room of a workmen's cottage. The boy's humble beginnings, and "the obstacles of narrow circumstances and even confined education" that he had to overcome, were noted in his Times obituary of 1848. Such circumstances made his rise to the highest ranks of the engineering profession all the more remarkable, and made him, too, a highly suitable subject for a biography by the self-help advocate, Samuel Smiles.

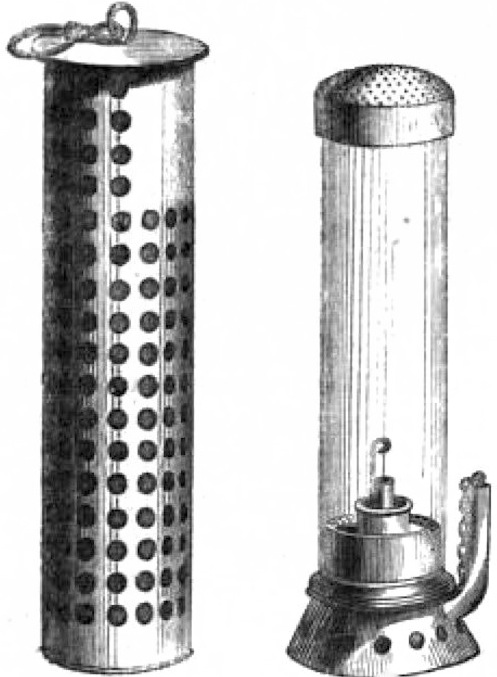

After working his way up from the most menial agricultural work, Stephenson started his career in the colliery with an equally menial task — picking coal clean of debris. He first showed his flair for invention by developing an improved safety-lamp for miners. Eventually he was able to turn his fascination with engines to some account, the first step to which was his appointment as assistant fireman at the age of about fourteen. From there he went on to become a highly skilled engineer, with the necessary tenacity and patience to tackle setbacks by adapting and refining his plans. He tested his first "steam-blast" locomotive in 1814: "On an ascending gradient of 1 in 450, the engine succeeded in drawing after it eight loaded carriages of thirty tons' weight at about four miles an hour," making it "the most successful working engine that had yet been constructed" (Smiles 71).

Stephenson had married in 1802, but his wife had died of consumption in 1806. She was not long outlived by their second infant, a baby girl. He was left with just the one child to bring up. He made sure that the boy, Robert, named after his own father, had the education that he himself had lacked, sending him to school in Newcastle and then to Edinburgh University. Robert became his highly proficient partner.

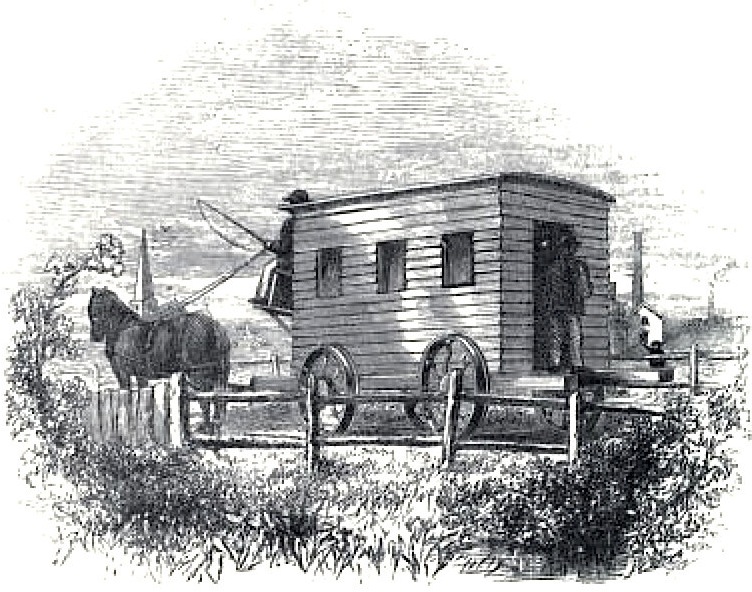

Left to right: (a) The Stephenson safety-lamp, with cover (Smiles 87). (b) The Rocket (click on the picture for more information). (c) No. 1 Engine, Darlington (Smiles 142).

One of the Stephensons' major achievements was designing and running the famous Rocket. This was the locomotive that won the much-heralded locomotive trials at Rainhill, on the new Liverpool to Manchester line, by reaching a maximum speed of twenty-nine miles an hour — "about three times the speed that one of the judges of the competition had declared to be the limit" (Smiles 217). By now George Stephenson had already set up a workshop in Newcastle, with the backing of two industrialists from Durham, putting his son in charge. Robert Stephenson & Co. quickly became "the most able of the early locomotive builders," more then proving themselves on the Stockton to Darlington line, which opened in 1825 (Kirby, "Stephenson, George"). Much of the credit for the Rocket goes to Robert, whom Smiles describes as now "devoting himself assiduously to the development of his father's ideas of the locomotive," and making his own "great additions" to those ideas (208). Some credit goes also to Henry Booth, the secretary of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway, who made important suggestion about increasing boiler capacity. There were, of course, other pioneers whose work in this field contributed to the Stephensons' success, notably Richard Trevithick. Besides, at this juncture George Stephenson had his own hands full with supervising the new line. But the impetus had come from him, and father and son were in close contact over the project. Its success had absolutely enormous repercussions, issuing in the railways mania of the Victorian period and transforming the British countryside, not to mention stimulating the development of the railway throughout the world.

Another of Stephenson's major contributions to railway technology was the establishment of the standard or Stephenson gauge, which would come into almost universal use. Smiles explains that this was "the gauge of wheels of the common vehicles of the country — of the carts and waggons employed on common roads" (132). It is just what might be expected from the man who in early childhood had watched the coal-wagons running on just such a gauge as they rattled past his front gate, and had been set to stop siblings and cows from entering their path.

Stephenson founded the Institution of Mechanical Engineers in 1847, the year in which both Jane Eyre and Wuthering Heights were published. He also served as its president. In this way he cut an important figure in the Victorian age. But he had nothing to do with the longer-established Institution of Civil Engineers in London. He had not been immune to criticism — had been suspected, for example, of seeing himself as "a railway supremo destined to survey, engineer and equip every line" (qtd. in Kirby, The Origins of Railway Enterprise, 45). He was indeed proud of what he had accomplished, as he had a right to be. Yet he more than once turned down a knighthood, seeing this and other honours as mere "empty additions to my name" (qtd. in Smiles 349).

Stephenson remarried for the second time early in the year of his rather premature death at the age of 67. His achievement is well summed up in the very fair and balanced entry on him in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. While finding that it was simplistic of Smiles to have promoted him as "the father of the locomotive," Maurice B. Kirby nevertheless writes:

Stephenson ranks as an engineering genius, a judgement validated by the fact that his principles and practices soon spread overseas. By 1870, the standard gauge, general uniformity of practice, and incremental advances in railway technology in the light of thorough testing and practical experience had been adopted on a global scale. Such a result undoubtedly rested on Stephenson's personal qualities — that combination of innate curiosity, profound common sense, and sheer practical ability that marks him out as the greatest of railway pioneers.

The picture below right is of the Experiment — "The sole passenger-carrying stock of the Stockton and Darlington Company in the year 1825 .... the forerunner of a mighty traffic" (Smiles 138).

Sources

"The Death of George Stephenson." The Times. 16 August 1848: 2. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 9 September 2014.

Kirby, M. W. The Origins of Railway Enterprise: The Stockton and Darlington Railway, 1821-1863. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

_____. "Stephenson, George (1781–1848), colliery and railway engineer." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Online ed. Web. 9 September 2014.

Smiles, Samuel. The Story of the Life of George Stephenson, Railway Engineer. Abridged ed. with Portraits and Illustrative Woodcuts. London: John Murray, 1859. Internet Archive. Uploaded by the University of Toronto. Web. 9 September 2014.

div class="nav-tile">

George

Stephenson