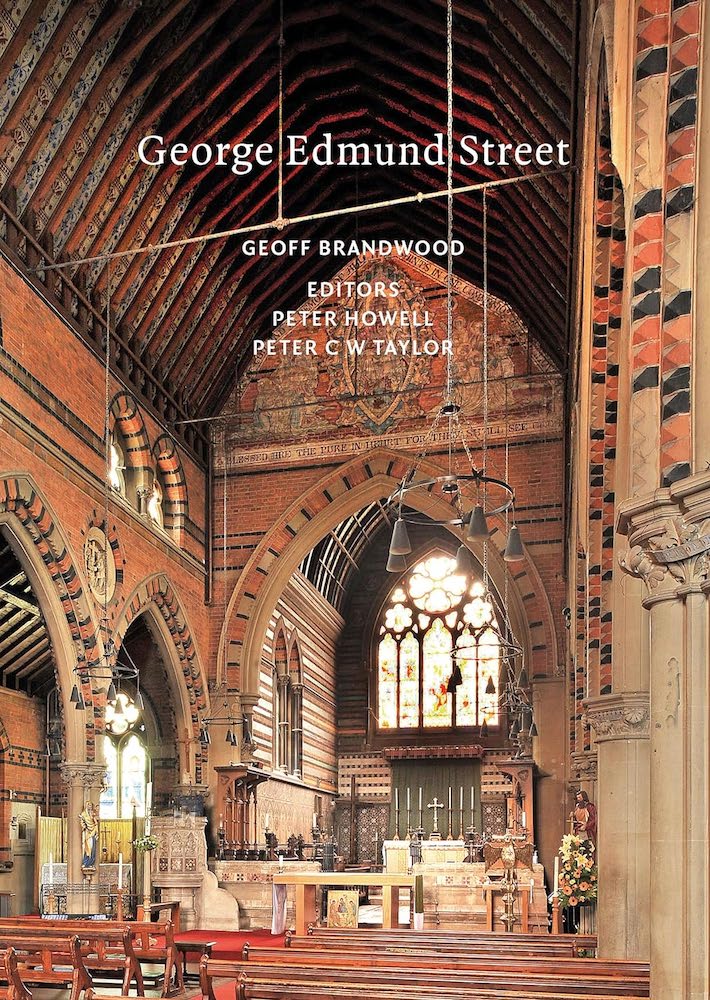

George Edmund Street left an impressive legacy of architectural work. In 41 years of practice, he completed around 500 projects, including work on cathedrals, churches and chapels, schools and colleges, public buildings and domestic residences. This extensive body of work was thoroughly researched and documented during the 1960s and 70s by the late Paul Robert Joyce, whose archive is now housed and catalogued in the library of the Paul Mellon Centre in London. In his Introduction to this book, the author, Geoff Brandwood, pays tribute to this detailed research, modestly describing his own task as "not so much adding new research as distilling Joyce's impeccable work into a modest compass" (Preface, x). The draft of this "distillation" was complete when Geoff Brandwood died, as we are told in the Foreword, "suddenly and unexpectedly" in November 2017. It was then edited and prepared for publication by Peter Howell, assisted by Peter C.W. Taylor.

From the introduction onwards, this surely definitive study is clearly structured and full of perceptive insights into the character and career of the architect, and includes a comprehensive catalogue of all his projects. The opening Chapter, "Life and Career", sets the scene, identifying the crucial events and key influences affecting Street's personal and professional development. This begins with his pupillage and time as assistant to George Gilbert Scott, in whose office, as a talented young draughtsman, he contributed to Scott's success in the competition for the rebuilding, after destruction by fire, of the Nikolaikirche in Hamburg. Completed in 1874, this was, for a time, the world's tallest building.

This chapter also provides insight into how the architectural ambience, at that time of very extensive church-building, was profoundly affected by the views of those religious leaders who favoured a return to the principles of the Roman Catholic source of the Anglican faith. The brief to their architects required churches which could accommodate the High Church ceremonies of worship, with emphasis on the structural and decorative style of architecture associated with the thirteenth-century historical peak of religious building, the Gothic style, created by the technical innovation of the pointed arch. This, according to those great influencers of the time, A.W.N. Pugin and John Ruskin, was "Christian Architecture," the deployment of which, in both religious and secular buildings, would miraculously reform their profanely industrialised society.

Street's smaller churches and secular buildings are described in detail in Chapters 2 and 3. Chapter 2, "Churches," expands on the influence of "The Gothic Imperative" and the range of possibilities within that style, emphasising Street's preference for the "solidity of character and sparing use of ornament" typical of early French Gothic (44, qtd. from Street's obituary in the Builder). This robustness of form is immediately apparent in his first independent commission, St Mary at Par, Biscovey, Cornwall, designed while he was still working for Scott.

St. Paul's within the Walls, Via Napoli, 58, Rome. [Click on this and the following images to enlarge them, and for more information about them.]

Trips to Italy in the 1850s expanded Street's vocabulary of decorative detail to include polychromatic decoration and the decorative use of brickwork, as in St Paul's-within-the-Walls, Rome, built 1873–76 (see Fig 2.3), his church in Chalfont St Peter, Buckinghamshire(see Fig 2.17), and The Church of the Holy Ghost, Genoa (see Fig 2.22).

Chapter 4 is devoted to Street's "major" works, both religious and secular. Such boundaries are sometimes rather uncertain, occasionally crossed by other references, as when St Paul's-within-the-Walls, Rome, appears briefly in Chapter 2 in company with the tiny church at Ardamine, presumably to illustrate the references to semi-circular apses and polychrome banded walls, and then appears in detail on its own account as a major project in Chapter 4. A distinction between secular and religious buildings might have made for a more useful division.

However, regardless of any other considerations, the status of The Royal Courts of Justice (The Law Courts) on the Strand in London can only be that of a major project.

The Royal Courts of Justice as finally built.

The architectural competition, involving the leading professional figures of the time including Scott, William Burges and Waterhouse, ended, as architectural competitions often do, in a division of opinions. E. M. Barry was premiated for his planning, and Street for his design of the elevations, which of course fitted his own plans, not Barry's. The impractical attempt to combine the two elements within a joint award was eventually ruled invalid by the Attorney General. Street's elevations had earned him the project, highlighting the current view (propagated by Ruskin in The Seven Lamps of Architecture [text]) that "Architecture" lies, not in the practical aspects of building, but in the otherwise unnecessary embellishments, which only the cultured and highly trained specialist – the Architect – is capable of bestowing on the otherwise mundane structure — or, Ruskin puts it in Chapter I of "The Lamp of Sacrifice": "Architecture concerns itself only with those characters of an edifice which are above and beyond its common use." An echo of this is still to be found in the wording of the Charter of the Royal Institute of British Architects, which defines architecture as "an art...tending greatly to promote the domestic convenience of the citizens and the Public Improvement and embellishment of Towns and Cities" (emphasis added).

Street's design, as it appeared in the Builder of 24 May 1867, following p. 358 in Vol.14, as a double-page spread.

The next two years saw proposals for an alternative site for the Law Courts and changes in the brief. The seventh design finally achieved approval and work began in 1870. Bombarded by criticism and plagued by constructional problems, the work was completed in December 1882, 121 weeks late. The contractors, Bull and Sons, sadly did not survive and went into receivership. Street himself had been greatly overstretched by the project.

"Not a popular building" declared Nicolaus Pevsner in 1952, but Geoff Brandwood maintains that the new Law Courts building, with its "fantastic skyline of varied roof shapes, gables and a soaring fleche" is "undeniably impressive" (158). Internally, the lofty vaulted Great Hall has generous windows on all sides, and Street's son, A.E. Street, seems right to have praised it: he claimed that it was probably "the lightest Hall in Europe" (qtd. 158).

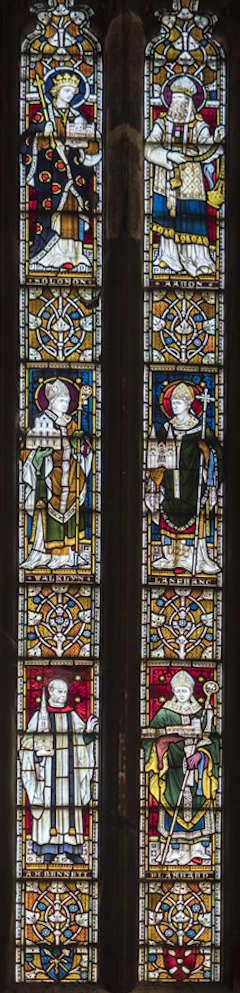

Four post-Biblical "founders of the church" in the Founder's Window at St Peter's, Bournemouth, designed by Street and made by Clayton and Bell.

Brandwood's comprehensive study is rounded off with two chapters by experts in associated fields: one on Street's stained glass, by well-known stained glass historian Martin Harrison, and the other on textiles, by Beryl Patten, embroidery historian, herself a tapestry designer (a paragraph or two of background on each of these contributors would have been welcome).

Stained glass was never commissioned by Street without the provision of detailed artistic direction to the artist – "even where the best artists in glass painting were concerned, the architect should decidedly have his say" (197, qtd. from A.E. Street). Attention is drawn to Street's concern for the provision of good light in the church, explaining why he preferred to have a high proportion of clear glass in his windows. Carefully tailored altar dressings were also considered essential, and Street designed many to furnish his churches. Examples illustrated here demonstrate vibrant colours and dramatic designs (see Figs 6.2 and 6.3). Both these chapters are valuable additions to the book, and, with the detailed chronological list of works provided by the Paul Joyce archive, confirm Brandwood's account as the definitive study of Street's oeuvre.

As editors, Peter Howell and the late Peter Taylor are due full credit for bringing this book to publication. Their work in editing the draft is a wonderful tribute to a scholar any reader would welcome as a friend and guide. In this connection, it seems a shame that the book, with its frontispiece portrait of Street and a later photograph of Paul Joyce (the author's dedicatee), should not have given Brandwood himself a little more space. He was not only a highly respected authority, but, as those readers who are members of the Victorian Society, or have joined the Campaign for Real Ale's Pub Heritage Group, will know, a much loved companion. A page or two of introduction* for the benefit of other readers – of whom there surely will be large numbers – would have been very welcome.

*See for example (offsite) the Victorian Society's Remembering Geoff Brandwood and the Campaign for Real Ale's Pub Heritage Group's Tribute to Geoff Brandwood.

Bibliography

Brandwood, Geoff. George Edmund Street, ed. by Peter Howell and Peter C.W. Taylor. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, on behalf of Historic England in association with the Victorian Society, 2024. Pback, £40.00. ISBN: 978-1802078121.

Created 2 May 2024