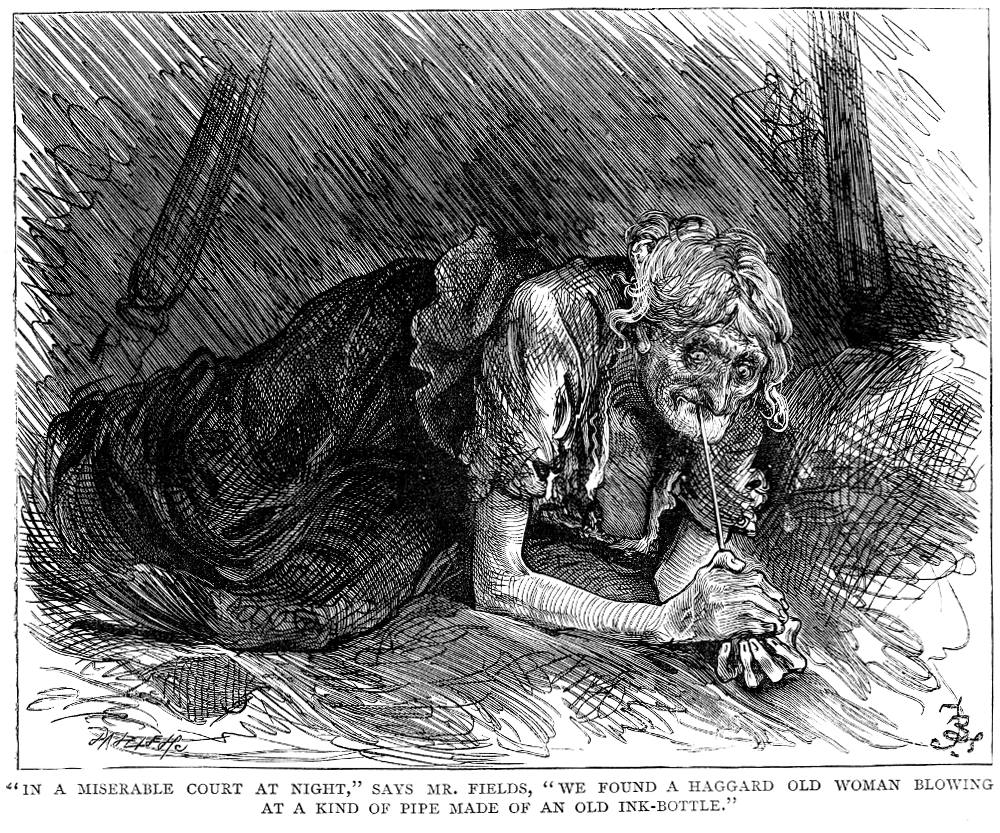

"In a miserable court at night," says Mr. Fields, "we found a haggard old woman blowing at a kind of pipe made of an old ink-bottle."." [The original Princess Puffer from The Mystery of Edwin Drood, the novel left incomplete at Dickens's death in 1870.] — Book 1, chap. xii. Frontispiece for John Forster's Life of Charles Dickens, twenty-second volume in in the Household Edition by Fred Barnard (1879). Composite woodblock Engraving by the Dalziels, 10.8 by 14 cm (4 ¼ by 5 ½ inches), framed. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Passage Illustrated: The Inspiration for the Opening of The Mystery of Edwin Drood

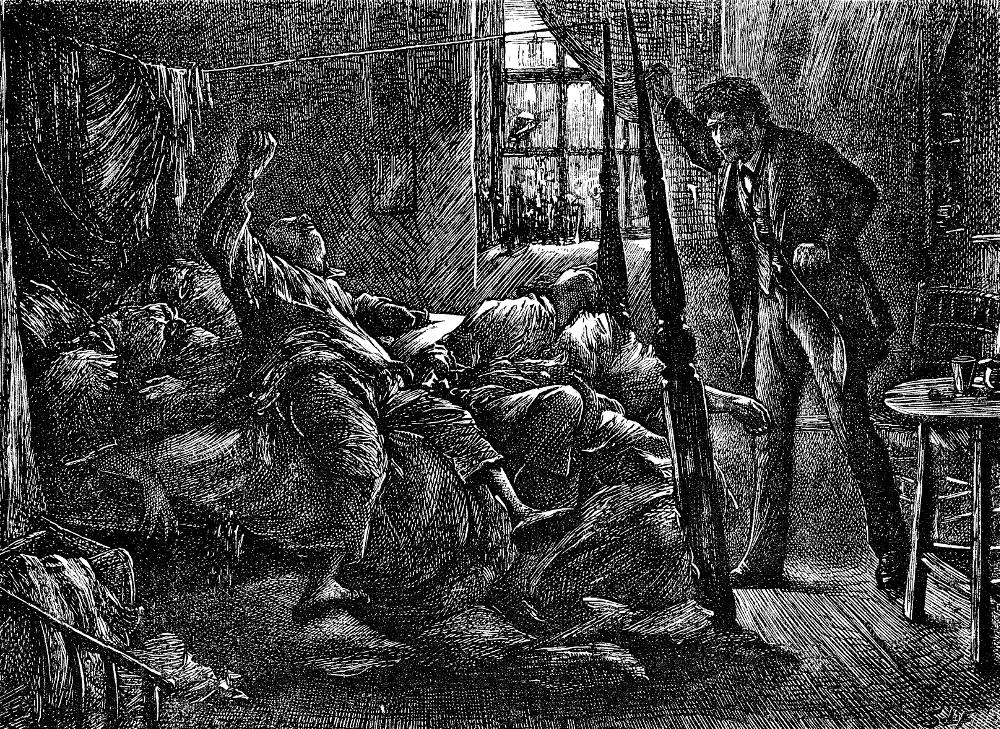

The backgrounds, too, were drawn from actual scenes, as for example, the opium-smokers' den which figures in the first and last illustrations; this was discovered by the artist somewhere in the East End of London; the exact spot he cannot recall, nor does he believe that Dickens had any particular den in his mind, but merely described from memory the general impression of something of the kind he had observed many years before. [Kitton, 211]

He had been able to show Mr. Fields something of the interest of London as well as of his Kentish home. He went over its "general post-office" with him, took him among its cheap theatres and poor lodging-houses, and piloted him by night through its most notorious thieves' quarter. Its localities that are pleasantest to a lover of books, such as Johnson's Bolt-court and Goldsmith's Temple-chambers, he explored with him; and, at his visitor's special request, mounted a staircase he had not ascended for more than thirty years, to show the chambers in Furnival's Inn where the first page of Pickwick was written. One more book, unfinished, was to close what that famous book began; and the original of the scene of its opening chapter, the opium-eater's den, was the last place visited. "In a miserable court at night," says Mr. Fields, "we found a haggard old woman blowing at a kind of pipe made of an old ink-bottle; and the words which Dickens puts into the mouth of this wretched creature in Edwin Drood, we heard her croon as we leaned over the tattered bed in which she was lying." [Book XII, Chapter i, "Last Days, 1869-1870," p. 291 in the 1872 edition's second volume]

In preparing this frontispiece for Forster's Life of Dickens Barnard had the advantage of being able to re-read the opening of The Mystery of Edwin Drood (1870) and review Fildes' twin illustrations of Princess Puffer's opium den (see below). Dickens describes the opium addict cogently in Chapter XIV, when young Edwin meets the narcotics purveyor in the Monks' Vineyard in Cloisterham:

Always kindly, but moved to be unusually kind this evening, and having bestowed kind words on most of the children and aged people he has met, he at once bends down, and speaks to this woman.

“Are you ill?”

“No, deary,” she answers, without looking at him, and with no departure from her strange blind stare.

“Are you blind?”

“No, deary.”

“Are you lost, homeless, faint? What is the matter, that you stay here in the cold so long, without moving?”

By slow and stiff efforts, she appears to contract her vision until it can rest upon him; and then a curious film passes over her, and she begins to shake.

He straightens himself, recoils a step, and looks down at her in a dread amazement; for he seems to know her.

“Good Heaven!” he thinks, next moment. “Like Jack that night!”

As he looks down at her, she looks up at him, and whimpers: “My lungs is weakly; my lungs is dreffle bad. Poor me, poor me, my cough is rattling dry!” and coughs in confirmation horribly.

“Where do you come from?”

“Come from London, deary.” (Her cough still rending her.)

“Where are you going to?”

“Back to London, deary. I came here, looking for a needle in a haystack, and I ain’t found it. Look’ee, deary; give me three-and-sixpence, and don’t you be afeard for me. I’ll get back to London then, and trouble no one. I’m in a business. — Ah, me! It’s slack, it’s slack, and times is very bad! — but I can make a shift to live by it.”

“Do you eat opium?”

“Smokes it,” she replies with difficulty, still racked by her cough. “Give me three-and-sixpence, and I’ll lay it out well, and get back. If you don’t give me three-and-sixpence, don’t give me a brass farden. And if you do give me three-and-sixpence, deary, I’ll tell you something.”

He counts the money from his pocket, and puts it in her hand. She instantly clutches it tight, and rises to her feet with a croaking laugh of satisfaction. [Chapter XIV, "When Shall These Three Meet Again?" pp. 109-110]

Dickens reintroduces her in Chapter XXIII, "The Dawn again," in a scene that Barnard appears to be realizing in the biography, set in the east end of London. Leaving his railway hotel in Aldersgate Street, near the General Post Office, John Jasper takes the familiar route from respectability to substance dependency:

He ascends a broken staircase, opens a door, looks into a dark stifling room, and says: “Are you alone here?”

“Alone, deary; worse luck for me, and better for you,” replies a croaking voice. “Come in, come in, whoever you be: I can’t see you till I light a match, yet I seem to know the sound of your speaking. I’m acquainted with you, ain’t I?”

“Light your match, and try.”

“So I will, deary, so I will; but my hand that shakes, as I can’t lay it on a match all in a moment. And I cough so, that, put my matches where I may, I never find ’em there. They jump and start, as I cough and cough, like live things. Are you off a voyage, deary?”

“No.”

“Not seafaring?”

“No.”

“Well, there’s land customers, and there’s water customers. I’m a mother to both. Different from Jack Chinaman t’other side the court. He ain’t a father to neither. It ain’t in him. And he ain’t got the true secret of mixing, though he charges as much as me that has, and more if he can get it. Here’s a match, and now where’s the candle? If my cough takes me, I shall cough out twenty matches afore I gets a light.”

But she finds the candle, and lights it, before the cough comes on. It seizes her in the moment of success, and she sits down rocking herself to and fro, and gasping at intervals: “O, my lungs is awful bad! my lungs is wore away to cabbage-nets!” until the fit is over. During its continuance she has had no power of sight, or any other power not absorbed in the struggle; but as it leaves her, she begins to strain her eyes, and as soon as she is able to articulate, she cries, staring:

“Why, it’s you!” [pp. 179-180]

Relevant Illustrations by Luke Fildes (April and September, 1870)

Fildes' Illustrations for the Last Dickens Novel (April through September 1870)

- 1870 Title Page for Edwin Drood

- 1879 Title Page [Master Humphrey and His Clock]

- 1. In the Court (April 1870)

- 2. Under the Trees (April 1870)

- 3. At the Piano (May 1870)

- 4. On Dangerous Ground (May 1870)

- 5. Mr. Crisparkle is Overpaid (June 1870)

- 6. Durdles Cautions Mr. Sapsea against boasting (June 1870)

- 7. "Good-Bye, Rosebud, Darling!" (July 1870)

- 8. Mr. Grewgious Has His Suspicions (July 1870)

- 9. Jasper's Sacrifices (August 1870)

- 10. Mr. Grewgious Experiences a New Sensation (August 1870)

- 11. Up the River (September 1870)

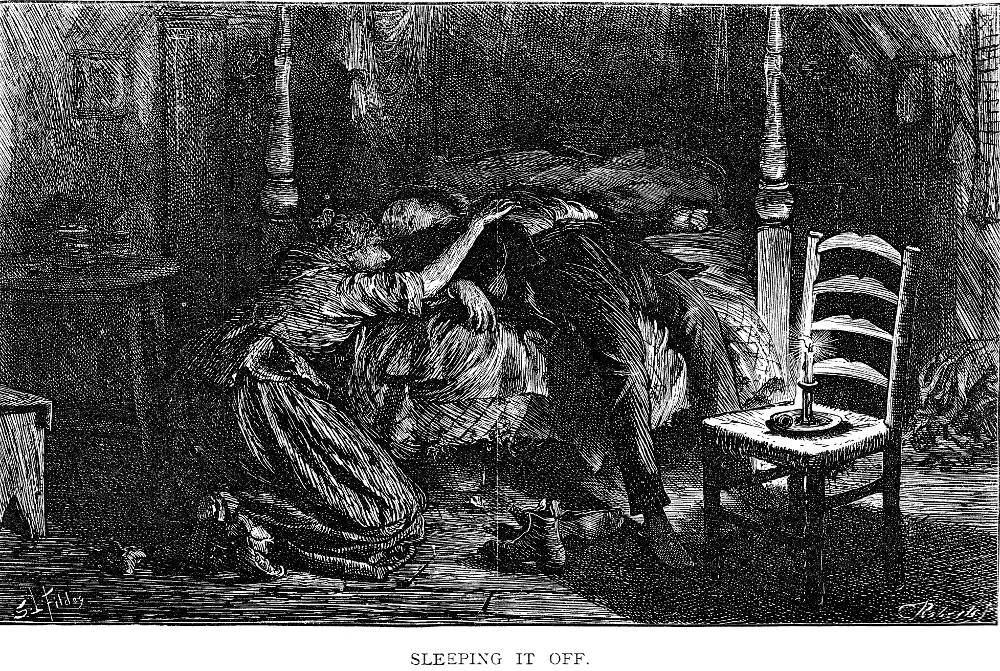

- 12. Sleeping It Off (September 1870)

Scanned images and text by Philip V. Allingham [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the images, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Ackroyd, Peter. Dickens: A Biography. London: Sinclair-Stevenson, 1990.

Barnard, Fred, et al. Scenes and Characters from the Works of Charles Dickens; being eight hundred and sixty-six drawings by Fred Barnard, Hablot K. Browne (Phiz), J. Mahoney [and others] printed from the original woodblocks engraved for "The Household Edition." London: Chapman & Hall, 1908. Page 584.

Dickens, Charles. The Mystery of Edwin Drood. Illustrated by Luke Fildes. London: Chapman and Hall, 1870.

_______. The Mystery of Edwin Drood and Reprinted Pieces. Charles Dickens. With Illustrations by S. Luke Fildes, R. A., E. G. Dalziel, and F. Barnard. The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1879, Vol. XX.

Forster, John. The Life of Charles Dickens. London: Chapman & Hall, 1872 and 1874. 3 vols.

Forster, John. The Life of Charles Dickens. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. 22 vols. London: Chapman & Hall, 1879. Vol. XXII.

Kitton, Frederic George. "Luke Fildes, R. A." Dickens and His Illustrators: Cruikshank, Seymour, Buss, "Phiz," Cattermole, Leech, Doyle, Stanfield, Tenniel, Frank Stone, Landseer, Palmer, Topham, Marcus Stone, and Luke Fildes. London: George Redway, 1899. 202-217

Created 15 September 2009 Last modified 10 January 2024