lfred Walter Bayes’s approach to a literary text was essentially a matter of faithful representation. If the writing specified a particular element then he recreated it in a visual form, so underlining the textual information. However, this does not mean that his designs were merely neutral replications of the source material. On the contrary, his approach to illustration was one in which he served the content of his text while highlighting key elements. Since Bayes did not, it seems, enter into personal collaborations with his authors, he was free to visualise as he saw fit, using his designs to provide vivid re-inscriptions of the letterpress while still managing to negotiate a small space in which he could position his own, more personal interpretations, pictorial embodiments of messages that ran in parallel with the author’s and maintained the currency of his art as a means to read.

This strategy enabled him to pursue a range of interests and form his art into a coherent whole. Running through all of his work is an emphasis on psychological drama and intense feeling. He also privileges his own readings of authorial tone, a capacity that allows him to shift from the domestic to the harsh realities of urban suffering, and from the prosaic to the imaginative domain of the fable and fairy-tale. He is equally adept, moreover, at working for an adult audience while offering programmatically simplified designs for the education and improvement of children.

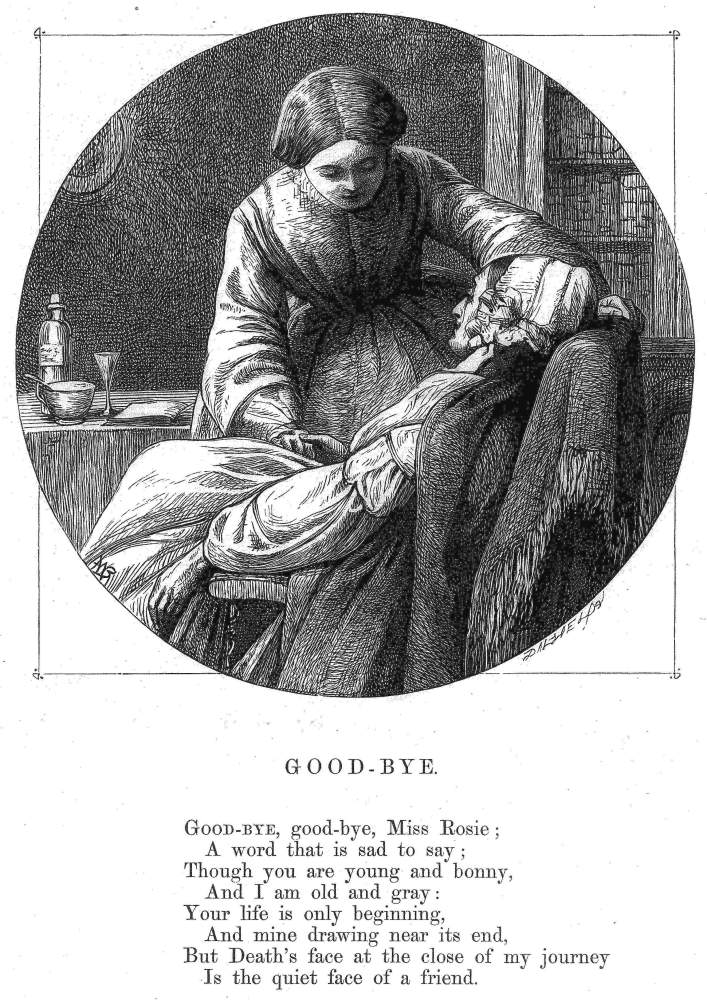

Good Bye.

Bayes is most characteristically concerned with still moments of reverie, contemplation and emotional reflection, and his work contains many images of characters engaged in moments of self-reflection. Never entirely successful in the representation of movement, his most striking images have a monumental stillness in which the subjects consider their thoughts. This motif extends the heroic self-examination of ‘Galileo Watching the Stars’ (The Burgomaster’s Daughter, 1893, p. 149) to the sad reflections of the ‘Poor Girl’ sitting on the grave in Everything in its Place (1869, p. 41). Such contemplation of the characters’ inner life resembles some aspects of the art of Pinwell, and both artists could be described as masters of introspection.

Bayes’s inwardness is exemplified by a fine illustration to Dinah Mulock’s pious verse, ‘Good Bye’ (p.13), in the Christmas gift book, A Round of Days (1866). Composed within a roundel, this image represents a distinct interpretation of its text. The poem focuses on the old woman’s demise as she bids farewell to ‘Miss Rosie’ while embracing hope in God; the illustration, on the other hand, is centrally concerned with the young woman who cares for her. The artist concentrates on her downward face and delicate gesture, so creating a scene of great tenderness. Its emotional effect is particularly achieved through the medium of the gaze. The young women’s half-closed eyes look down on her subject and her expression suggests the reverence and compassion with which she treats her charge.

Illustrations by John Everett Millais — Left to right: (a) The Miller's Daughter from the Moxon Tennyson. (b) St. Agnes Eve from the Moxon Tennyson. (c) "Mark", she said, "the men are here" illustration for Framley Parsonage. (d) The Crawley Family illustration for Framley Parsonage. [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

Such emotionalised looking typifies the artist’s manipulation of the dynamics of the gaze. This linking of characters through the medium of how they look at each other is of course a fundamental device, and the illustrator may have been influenced by the significant gazing at work in Pre-Raphaelite illustration, principally in Millais’s designs for Tennyson and Trollope. He is principally concerned with the gaze of close proximity: characters not only gaze at each other, they typically peer into each other’s face or look at each other to the exclusion of others.

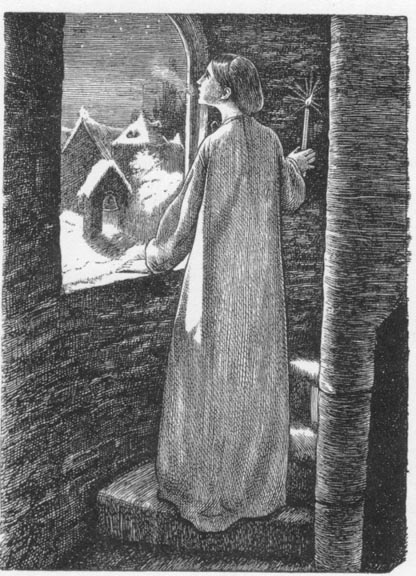

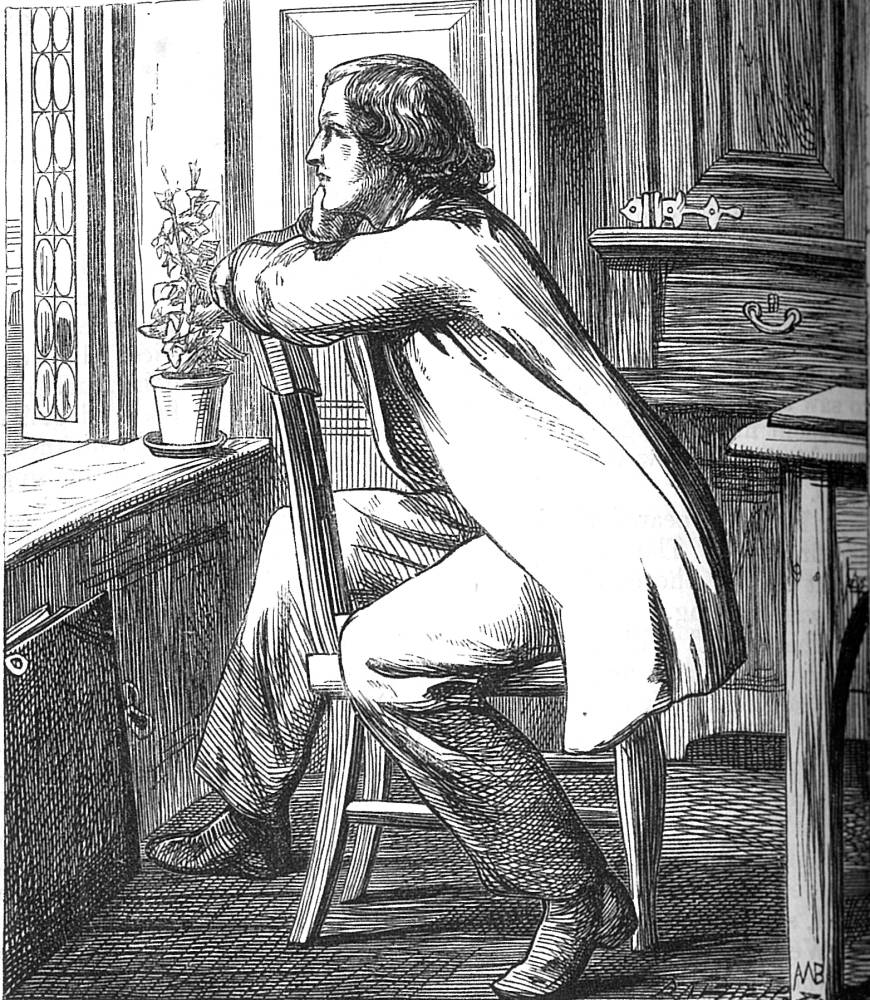

This psychological tension focuses the many scenes of illness and dying found throughout the Andersen texts, especially in Stories for the Household (pp. 46; 202; 273; 290). The gaze is also turned inwards: as in many Pre-Raphaelite designs, Bayes’s characters characteristically engage in a process of self-examination. In the opening design for What the Moon Saw, the emphasis is firmly placed on introspection. This image of the storyteller, as he is about to hear what the moon is going to tell him, is a sophisticated showing of his inner thoughts. He is said to be in a ‘desponding mood’ in which his ‘hands and tongue seem alike tied, so that [he] cannot rightly describe … the thoughts that are arising within [him]’ (2), and Bayes depicts him as an appropriately contorted and awkward figure, his limbs wrapped around the chair, looking out through the window. With its emphasis on reverie, the illustration materialises an intangible event; the narrator looks outward, but his abstracted gaze into an imagined space occupied by the moon is a metaphor for looking within.

Left to right: (a) What the Moon Saw and (b) The Elf King’s Feast by Alfred Walter Bayes. [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

Bayes goes on to provide vivid representations of the content of the self-reflection, the dreams and imaginings enshrined in Andersen’s text. To some extent, this is purely a matter of following the directions: Andersen ranges from exotic orientalism to medievalism, from fairy land to the everyday, and Bayes underscores the unsettling nature of his visions by presenting a visual equivalent. His fairy-tale idiom is exemplified by ‘The Elf King’s Feast’ from What the Moon Saw, and reprinted in Stories for the Household (p.361). Andersen specifies a catalogue of details, and Bayes visualises each of them, from the King himself to the ethereal elf girls wearing ‘shawls’ of ‘mist and moonshine’ as they dance in an indeterminate space (p.360). Shifting between each of these subjects, Bayes combines Andersen’s disparate characters within a single image which is both ethereal and intensely material. The girls are drawn with a delicacy that recalls the fairy illustrations of Arthur Hughes, while the earthly inhabitants have a prosaic directness. Moving easily between visual registers, Bayes reaffirms the curious incongruities at the heart of Andersen’s prose.

Equally important is the representation of the animals milling around in the bottom foreground. Having already taken ownership of Andersen’s writing of the psychological and treated it in his own terms, he privileges the author’s fable-like emphasis on anthropomorphised creatures, on lizards, birds, pigs and even earth-worms that speak and act as people. Focusing on the traditional childish delight in the animal world, he visualises a slightly menacing menagerie, sharply drawn and amusingly characterised. What distinguishes his approach, however, is his capacity to realise Andersen’s abolition of the conceptual space between human and animal, incorporating small details and gestures which are not contained in the text but, for children especially, enable the reader/viewer to engage with the imaginative fusion of the two domains of reality and accept the notion that animals embody the moral characteristics of humans.

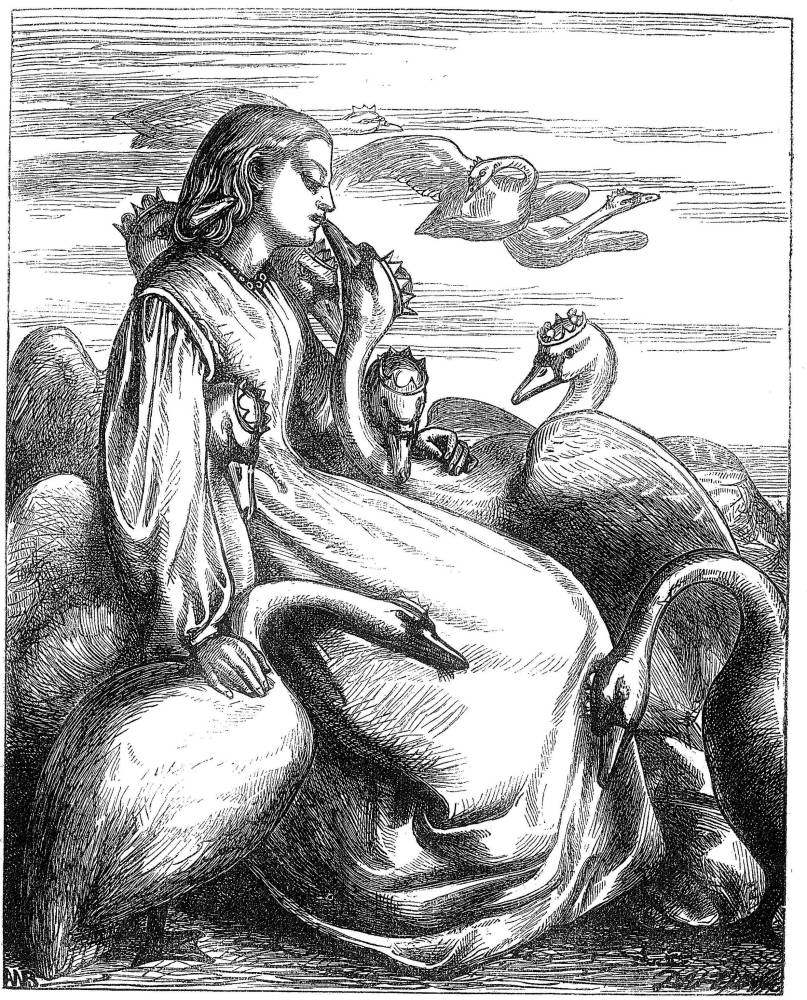

Eliza and Her Brothers.

In ‘Eliza and Her Brothers’ (Stories, p.565), the artist erases the difference between animal and human. Andersen focuses on their transformation into Eliza’s brothers, but Bayes, diverging from the text, shows them surrounding her in their swan-forms but behaving as if they were her human siblings. This notion is vividly conveyed by one of the swans pushing his head under her arm like a mischievous younger brother; by another laying his head on her lap; and a third fiddling with her hair. The arrangement stresses the psychological bond between them, and Bayes further suggests their unanimity by creating visual interconnectedness between the sinuous, heraldic arabesques of the swans’ necks and the curving line of their sister’s sensuous figure and swelling dress.

By making these visual linkages and providing extra-textual details, Bayes playfully intensifies the strangeness of his animistic images. He accentuates the writer’s effects, highlighting the weird effects of juxtaposition and fusion, by presenting his images in an extremely realistic way which does not differentiate between the imaginary and the ‘real’. Like Tenniel, whose showing of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) make them seem as if they could literally happen, he magnifies the sense of the dream-like by presenting everything in the same objective register. Andersen’s voice is prosaic and dead-pan, an accounting of the imaginative unimaginatively, and Bayes’s visual language creates the same type of matter-of-fact reportage.

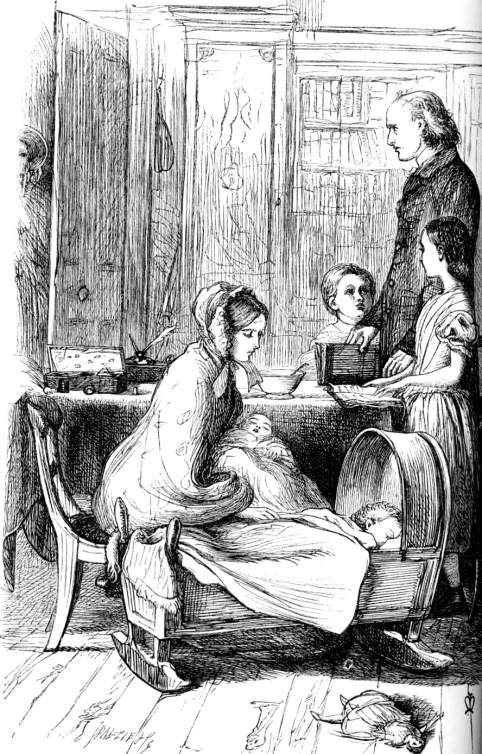

He characteristically presents a visual oxymoron in which the fantastic intermingles with domestic settings. Andersen’s tales are all essentially ‘for the household’ and the illustrations highlight their settings by placing the characters in a series of rooms which include details of the furniture, the grain in the wood, decorative hinges, floor-boards and ceilings, carvings on the banisters, and other prosaic items. This emphasis on the showing of the fantastic in the context of plausible spaces insists on the status of Andersen’s tales as an invented folk-lore derived from the oral traditions of story-telling.

More specifically, the illustrations highlight the effects of the uncanny as defined by Freud in his classic essay of 1909. According to the Freudian formulation, ‘uncanniness’ is created when the ‘unhomely’ (or unfamiliar) appears within the setting of the ‘homely’. Andersen’s texts place the strange within the comfortable domain of the fireside, and the illustrations magnify the sense of uncanniness by investing the unfamiliar with the same, apparently casual realism as the showing of a table or a chair. Intended to create a ‘magical’ uncertainty, such images confound expectations and view the world through the half-closed eyes of reverie, the state of semi-hallucination that Victorians described as a ‘waking dream’.

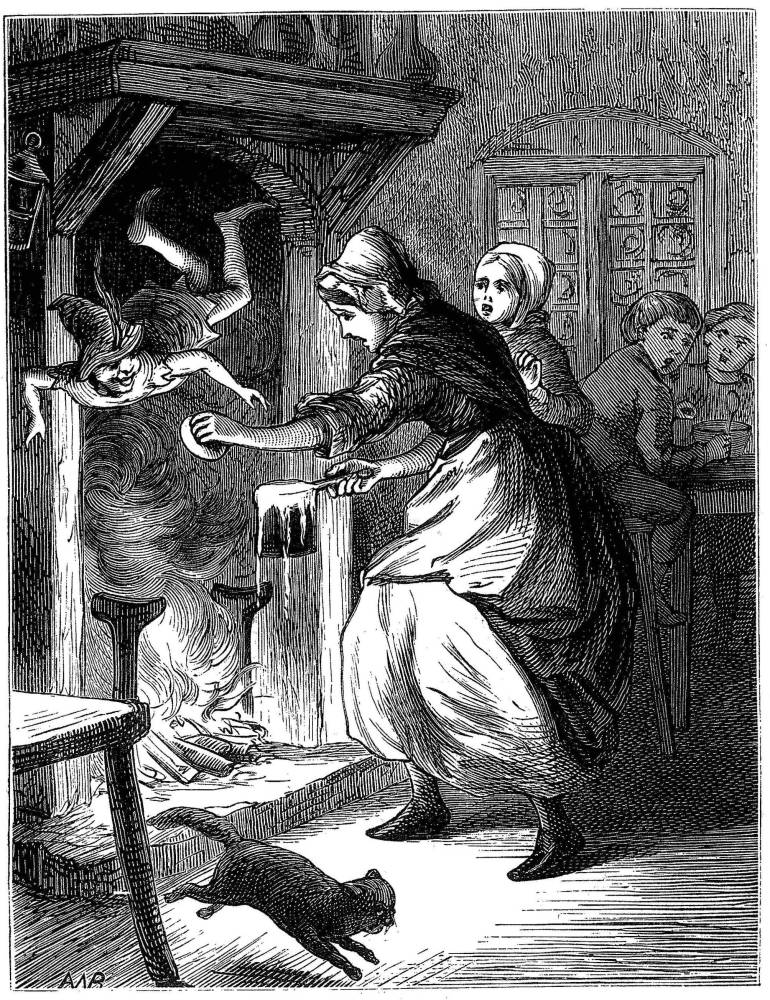

The Hillman and the Housewife.

Bayes pursues this idea in his treatment of other fairy-tale material, so repeatedly pointing to the genre’s calculated strangeness. Some of his most unsettling designs are for Julia Ewing’s fairy tales, which first appeared in Aunt Judy’s Magazine (1869–71) and were subsequently reprinted in Old Fashioned Fairy Tales [1882]. In Ewing’s tales the everyday is subverted by the intermingling of the unexpected and the prosaic, and Bayes offers visual treatments which are both menacing and droll. In ‘The Hillman and the Housewife’, the artist gives a vital showing – one of his best representations of movement – of the sprite ‘tumbling down the chimney’ (Old Fashioned Fairy Tales, p. 14). The story concerns spoilt milk and a saucepan; but the illustration stresses the figure’s entrance, a hovering form surrounded by domestic items shown merely as ‘facts’, Pre-Raphaelite particularization at the service of the dream.

Bayes’s capacity to create these ambiguities marks him out as a highly effective illustrator of this sort of material, and the nature of his responses gives him a strong advantage over many others. Able to mediate between the known and the unknown while never losing sight of emotional drama, Bayes registers the complexity and challenge of texts that were regarded as the time of production as uncomplicated stories for the nursery, but can now be read as emblematic signs of the many tensions lying at the heart of Victorian culture.

Last modified 30 October 2012