harles Edmund Brock (1870–1938) is usually categorized as an artist who worked in the ‘Cranford style,’ a faux Regency imagery that was originated by Hugh Thomson in his designs for Elizabeth Gaskell’s novel when it was issued by Macmillan in 1891. Brock was certainly influenced by Thomson (Muir 20; Hodnett 195), and there is a close familial relationship between Thomson’s illustrations and Brock’s. Brock imitated many aspects of Thomson’s art, and both artists focused on the representation of the social mores and domestic dramas of privileged elites as they featured in novels by W. M. Thackeray, Charles Reade and especially Jane Austen. In this sense they were united in creating a highly idealized visual world that imaged the Regency period as an intimate space in which settings and costumes are as important as delineation of characters and situations.

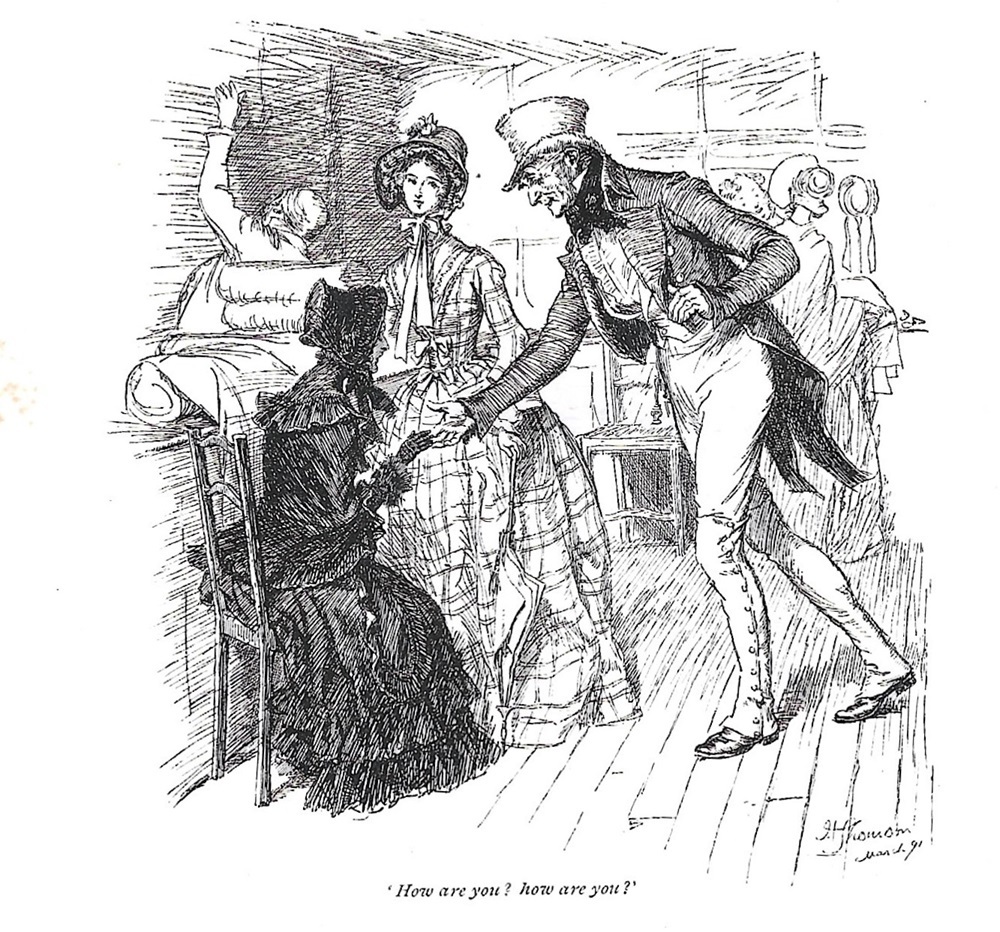

Two illustrations showing the similarities between the work of Thomson and Brock. Left: One of Brock’ illustrations in Cowper’s The Diverting History of John Gilpin; and right: a design by Thomson for Gaskell’s Cranford.

On some occasions their imagery is practically interchangeable, and a comparison between two typical scenes exemplifies their stylistic proximity: one is Brock’s treatment of a meeting in William Cowper’s The Diverting History of John Gilpin (1898), and the other is from Thomson’s version of Gaskell’s Cranford (1891). Both focus on tightly knit, domestic settings with the characters crammed in small spaces, both use a delicate line combined with decorative detail, and both emphasise Regency costumes and the fashionable paraphernalia of the 1820s. The effect is one of pleasing escapism, figuring a world of nostalgic romance which appealed to late Victorians as an alternative to nineteenth century industrialization and asserts a certain sort of genteel idleness in a ‘modern’ society that was possessed by capitalist ethics and the restlessness of ‘progress.’ Such Regency imagery was, in short, an idyll, a place also represented in the art of Kate Greenaway and Randolph Caldecott. Brock and Thomson were linked in presenting this dream-world and some critics have viewed their shared vision as lacking in artistic integrity and accuse them of offering their readers little more than a sort of anodyne fantasy.

That position is debateable, but it is certainly the case that Brock was more than an imitator of Thomson and was a more complex artist than one solely concerned with emollient visions of the past. If Thomson were entrenched in his escapist idiom, the same cannot be said of Brock, who adopted the Regency style but excelled in other forms as well, was versatile, inventive, and sensitive to the diverse demands of his literary texts. As Edward Hodnett remarks, Brock had a ‘talent for interpreting [literary material] more robust than [the writing] assigned him’ (195), and was far more than a practitioner of conventionalities. Indeed, his range extended from social observation of the genteel to the picturing of situational comedy and the absurd; he was similarly adept at visualizing historical characters and events and deeply felt emotion. Thomson is so often accused of narrowness, an artist bound by an iconography of his own making, but the same could not be said of Brock.

Comedy, Fantasy, History

Brock’s capacity to illustrate comedy is exemplified by his first substantial commission, Hood’s Humorous Poems (1893). Brock’s aim in this book, in strict accordance with the text, is to make the reader/viewer laugh – an objective projected by the smiling sun-face on the front cover, which he designed in addition to the dozens of comedic illustrations contained in the pages. His comedic strategies include caricature, presenting lower-class types which recall the satire of John Leech, and he also deploys slap-stick burlesque and – in contrast to the broadness of most of the humour – a subtler form of arch drollery which he enshrines in strange, witty juxtapositions of figures and situations.

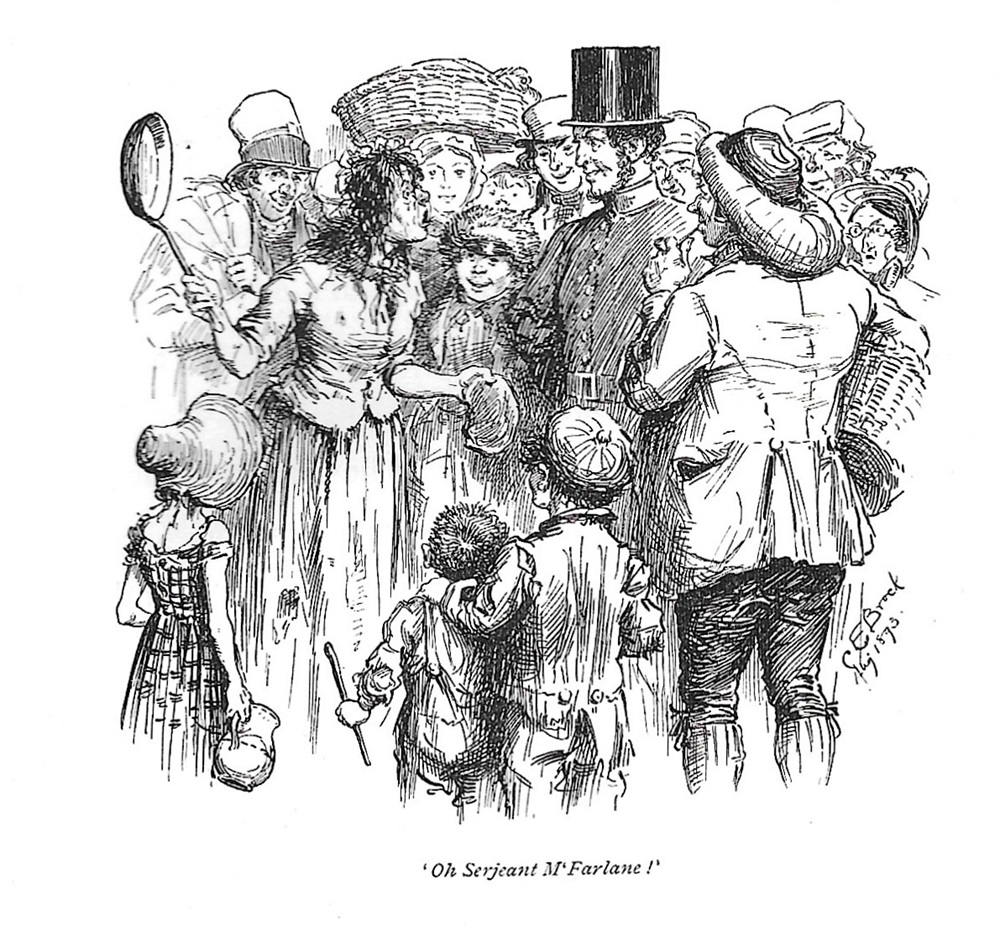

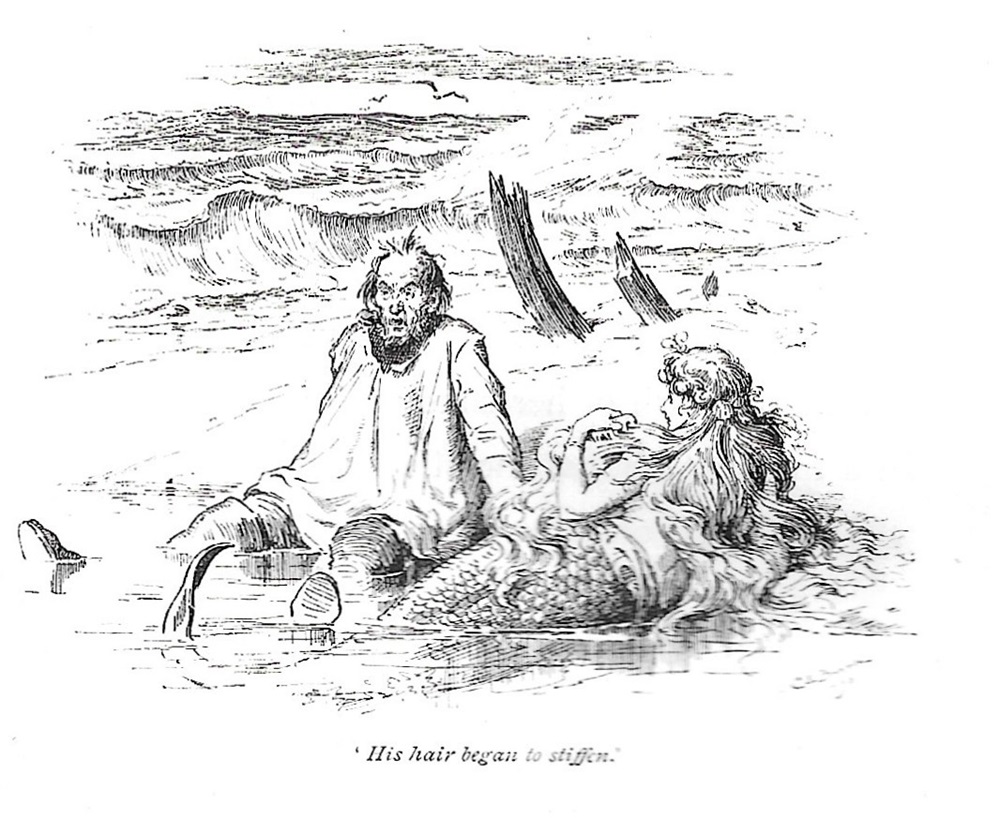

His interest in physical humour is exemplified by his designs for Thomas Hood’s ‘Epping Forest’ in which he focuses on the falls of the huntsmen – a type of comedy that can also be found in the equestrian farces of Georgina Bowers. Here the humour is just a matter of pratfalls. In contrast, the artist’s class-based comedy is enshrined in his illustrations for ‘The Lost Heir,’ visualizing the main character as a manic ‘sally,’ ‘Bedaubed with grease and mud’ (Hood 193), cavorting crazily around the streets and surrounded by working people; as in John Leech’s cartoons, Brock particularizes the proletarian faces and costumes, offering a type of mocking humour that is predicated on the notion of the stupidity of the undereducated and seems distasteful to modern observers but appealed to the Victorian middle-classes. Brock adopts a more understated approach, however, in his designs for ‘The Mermaid of Margate’ as he visualizes the droll, ironic incongruity of the encounter between the ‘Fishmonger’ (43) and a voluptuous denizen of the sea; most amusing is the scene where Brock draws a sharp contrast between the baffled tradesman and the flirtatious mermaid, who playfully tugs at her hair. Clearly, this fishmonger has fallen in love with a strange fish, and putting her on the plate seems very odd indeed.

Three works by Charles Brock, demonstrating his comedic versatility. Left to right: (a) Knockabout humour for ‘Epping Forest,’ a combination of farce and falls; (b) The scabrous comedy of ‘The Lost Heir’; and (c) the surreal dislocations of ‘The Mermaid of Margate,’ juxtaposing a fishmonger and a piscine beauty.

The effect of all of these comical situations, which contemporaries described as ‘excellently humorous’ (‘Belle Letters’ 345), is heightened by Brock’s use of realism as a means to validate the scenes by placing them in detailed, concrete settings; his focus on costumes, furniture and domestic items also intensifies the humour by suggesting that such ludicrous narratives could happen in reality. Brock firmly believed in this sort of verisimilitude and based his drawings on observation of real-life costumes and curios, which he and his brother, Henry Brock, collected as studio props (Houfe 75).

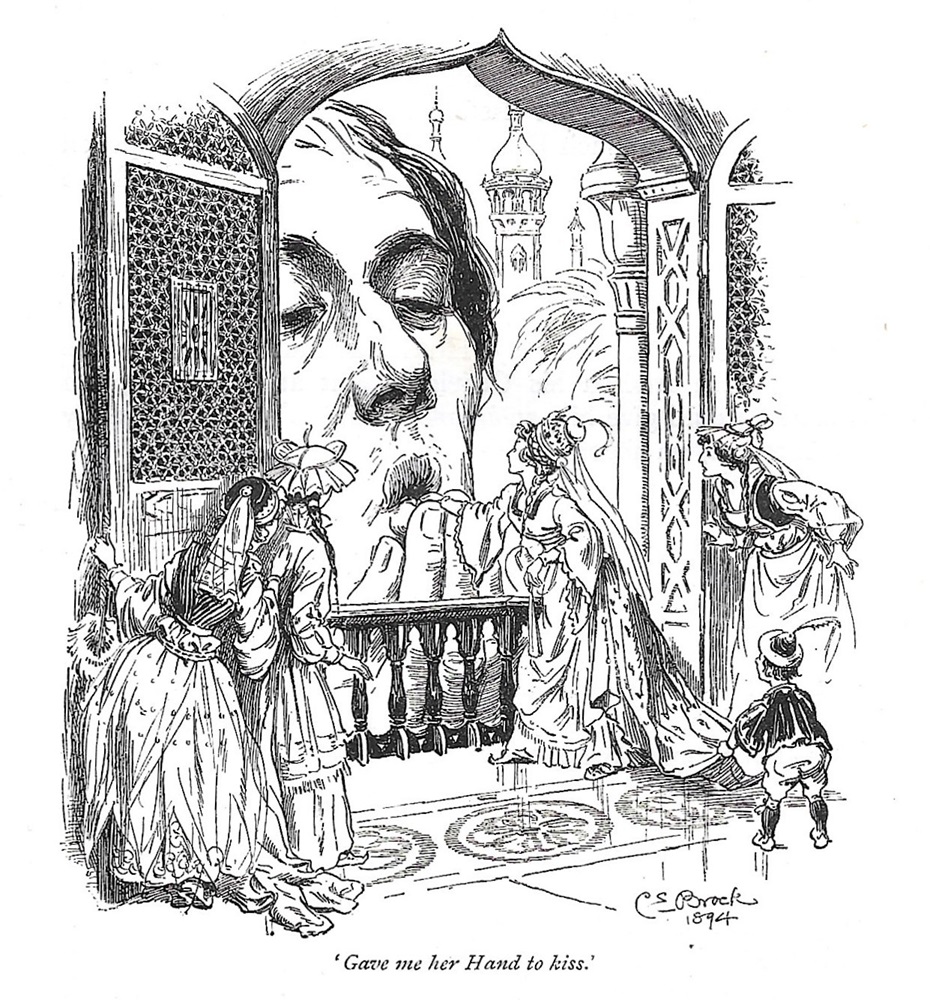

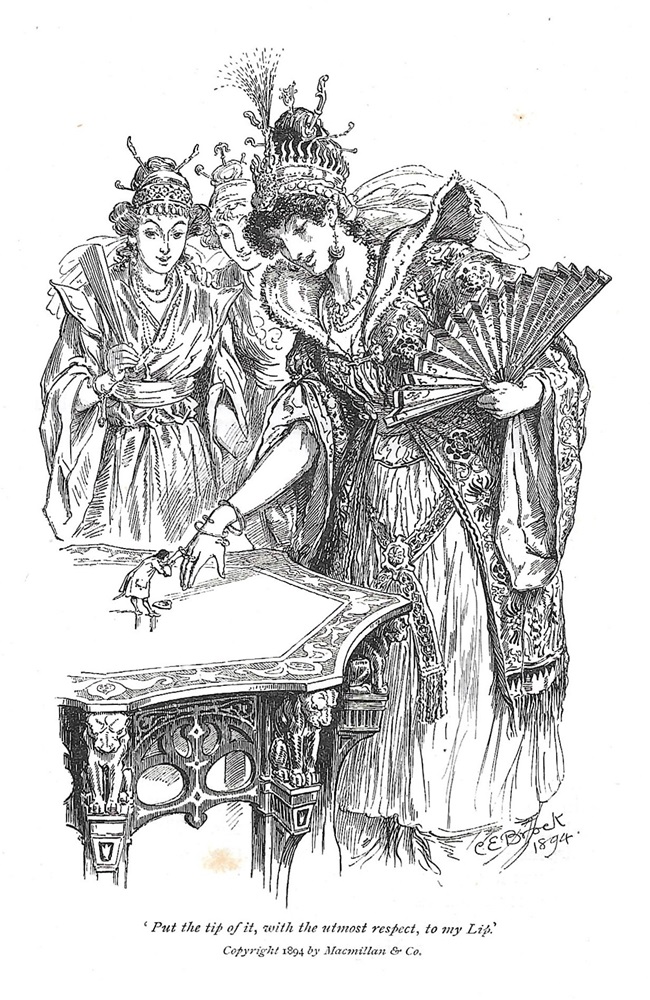

Brock’s sense of the material was put to another use in his illustration of fantasy, in each case giving the fantastic an added strangeness by showing the impossible as if it were possible. His greatest achievement in this respect was his series of illustrations for Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels (1894). Brock magnifies the weird incongruities of Swift’s allegory by depicting disparities of scale in a plausible way, to disconcerting effect. In the words of Percy Muir, Brock’s ‘contrasts in size’ are brilliantly realized, especially in the scene of Gulliver ‘peering through a middle-storey window to kiss the Queen’s hand’ (201). This image unsettles the viewer by reproducing the Lilliputians’ sense of largeness and smallness as they contemplate Gulliver’s huge nose and face, drawn in dynamic lines, which Brock measures against the intricate detail of the tiny faces and of the costumes worn by the figures in the foreground. Essentially it is a Big and Small joke, realized by contrasting generalized description with the miniscule modelling of tiny, intricate lines. The situation is reversed in Gulliver’s kissing of another hand – this time the hand of the vast Brobdingnagian queen, with the adventurer reduced to the size of a Lilliputian. In this case, again, the incongruity of disparate scale is presented as if it could happen in reality.

Brock’s accomplished treatment of Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels, with the voyager engaged in the kissing of two hands – one tiny (left), and one gigantic (right).

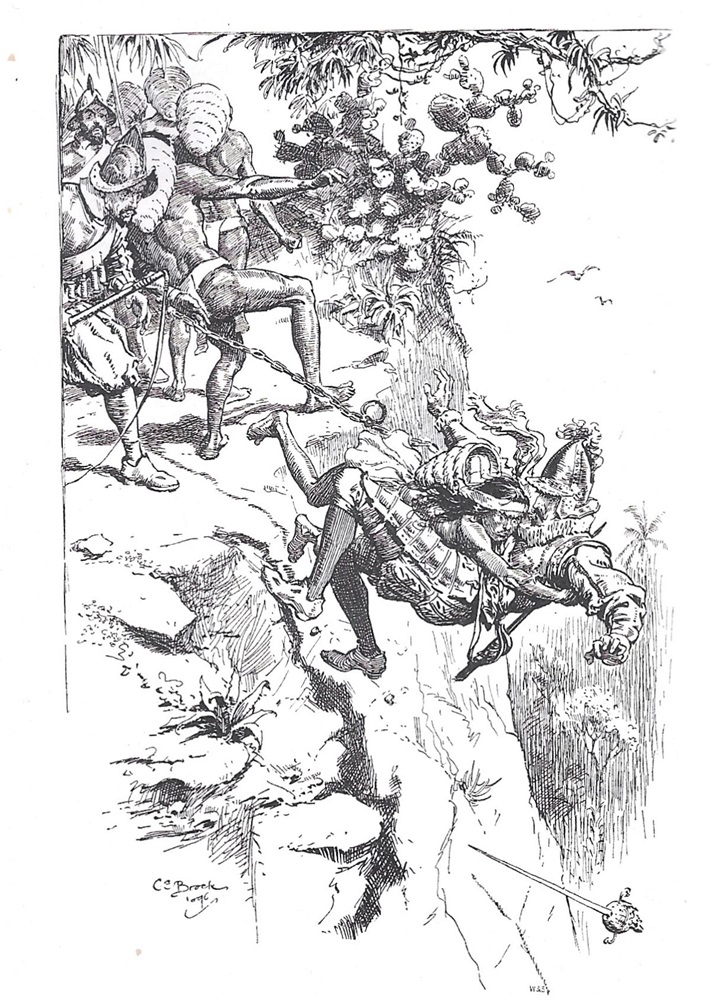

Brock’s powers of imaginative realization thus make him an ideal illustrator for subjects as diverse as comical poetry and the dream-like imagery of Swift. His versatility can be further traced in his treatment of medievalism, especially in his visualization of Scott’s The Lady of the Lake (1898). In this book, Brock displays his usual interest in costume, picturing an iconography of realistically rendered kilts along with a factual representation of armour and weapons. More familiar with the elaborate dress of the Regency, he registers an interest in antiquarianism as well. However, Brock’s figures are far mor dynamic than his polite ladies and gentlemen; though some of his scenes are static tableaux in echo of the ‘Cranford style,’ most involve dramatic confrontations, crises, chases, violence, and intense emotion. He also adopts this illustrative strategy in his response to Charles Kingsley’s Westward Ho! (1896), depicting the text’s rapid transitions and strange encounters in a series of vibrant compositions.

Two of Brock’s dynamic designs in historical novels: left, showing a scene from Scott’s The Lady of the Lake; and right, from Kingsley’s Westward Ho!.

Brock was, in short, far more than a ‘Cranbrook’ illustrator and should not be categorized – or dismissed – as an imitator of Thomson. Never less than versatile, his changing responses allowed him to produce a prodigious number of pen-and-ink and colour illustrations for a wide range of texts; initiated in the 1890s, his work continued into the 1930s. He was, in particular, an illustrator of Dickens, a writer whose range and complexity was well-matched by Brock’s inventive designs.

Bibliography

Primary

Cowper, William. The Diverting History of John Gilpin. London: Aldine, 1898.

Gaskell, Elizabeth. Cranford. Illustrated by Hugh Thomson. London: Macmillan, 1891.

Hood, Thomas. Hood’s Humorous Poems. Illustrated by Charles Brock. London: Macmillan, 1893.

Kingsley, Charles. Westward Ho! . Illustrated by Charles Brock. London: Macmillan, 1896.

Scott, Walter. The Lady of the Lake. Illustrated by Charles Brock. London: Service & Paton, 1898.

Swift, Jonathan. Gulliver’s Travels. London: Macmillan, 1894.

Secondary

‘Belle Letters.’ The Westminster Review 140 (July–December 1893): 342–346.

Hodnett, Edward. Five Centuries of English Book Illustration. Aldershot: Scolar, 1988.

Houfe, Simon. The Dictionary of Nineteenth Century British Book Illustrators. Woodbridge: The Antique Collectors’ Club, 1978; revd. ed., 1996.

Muir, Percy. Victorian Illustrated Books. London: Batsford, 1971; rev. ed. 1985.

Created 19 August 2024