he Tournament, or, The Days of Chivalry (1840) was Richard Doyle’s first book, produced when he was sixteen years of age. Presented as a pastiche of the real-life reenactment of a joust, the Eglinton Tournament (1839), and consisting of only six lithographed pages and a paper cover, it was printed by J. Dickinson as a vanity project designed to showcase the youthful artist’s talent and circulated among family and friends; Count D’Orsay, among others, perused its pages (Dick Doyle’s Journal, viii). Fifty copies were originally printed, although 150 (Engen 194) were ultimately produced, and some were sold to the general public. With this few being issued, The Tournament is today a book of the utmost rarity: in addition to copies in the British Library and the Victoria & Albert Museum, it can only be found in three institutions internationally; a few may survive in private collections, and the copy illustrated here is in my possession.

That it appeared at all is remarkable. Doyle’s home education involved the production of artwork to be assessed by his father the cartoonist John Doyle (known as ‘HB’), and The Tournament could have been another manuscript that never progressed into print. Richard was certainly unsure of ever seeing it appear, noting in his Journal for January 8th 1840 that there is only ‘some chance’ (4) of getting the work published, later observing how he was ‘impressed with the belief’ that he would be disappointed, and can only ‘imagine’ seeing it in a print-seller’s window; he nevertheless visualized that moment in a small design of Fores’ shop (5). Doyle was hugely excited when the book did make it into the world, although its gestation had always been difficult; he struggled with the process of drawing on the lithographic stone – his father’s medium – and admits to spoiling at least two designs (Journal 8).

Bearing in mind these uncertainties, Doyle’s first book is self-assured, especially for such a juvenile hand, and a work of considerable significance. It establishes the themes and styles he would develop in a career lasting more than thirty years, prefiguring his social satire and comedic strategies, and it embodies his compositional devices, motifs, and liking for grotesque and amusing characterization. The Tournament is of special interest, moreover, as the prime example of Doyle’s capacity to fuse social commentary and pastiche, using his book to anatomize the absurdities of the Eglinton Tournament, and to provide a droll parody of medieval art.

The Contexts of The Tournament and Social Satire

The Eglinton Tournament was organized by Lord Eglinton and held at his castle in Ayr, Scotland, in the August of 1839. Essentially a part of the Gothic Revival (Stamp 106), it was intended to celebrate a highly idealized version of the medieval past in a period when the Industrial Revolution was beginning to transform British society and Utilitarianism was the dominant mode. Though attended by many thousand members of the working classes, it was an essentially an aristocratic self-indulgence, a display of privilege with peers of the realm dressing up in costumes and armour as they took part in reenactments of jousts and knightly duels, courtly rituals and various forms of display. The weapons, suits of armour and tunics were procured from a variety of makers, and the estate was bedecked with banners, pavilions, marquees and flags to create the ultimate medieval theme-park. Though only lasting three days (28–30 August 1839), it cost Eglinton a fortune: estimates vary, but one commentator writing at the time put the bill at £20,000 (Aikman 6), a sum equivalent to 2.6 million in sterling of 2023.

Unfortunately, the event was a flop and a wash-out: quite literally. On the first day, 29 August, it rained heavily, forcing the activities to be abandoned. The next couple of days were better, but the ‘unpropitious’ weather (Aikman 7) had reduced the site to a quagmire, and it was practically impossible to perform the various acts of chivalric militarism. Mired in heavy mud, the vast crowds of spectators were likewise reduced to soggy misery, an unpleasantness accentuated by a shortage of local accommodation and catering, and by the incapacity of the over-crowded train service to evacuate those who sought to escape the drear conditions.

Far short of the glamour it aimed to recreate, the Eglinton Tournament was in reality a mud-bath for re-enactors who, in any case, had none of the skills of medieval knights, and thrashed around in front of cold and bemused spectators. It was, in short, a complete farce, and after the event Lord Eglinton’s reputation was badly in need of good publicity.

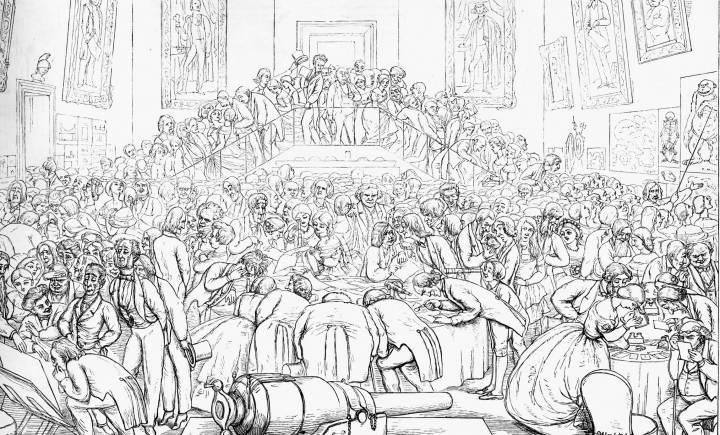

Two highly romanticised versions of the Eglinton Tournament: Left: Nixon’s treatment of the Melee (1843); and Right: Courbould’s view of the participants in medieval garb (1840).

The tournament’s failure was largely rewritten in elaborate picture-books which indulgently presented the event as a romantic vision of heraldic splendour. James Aikman wrote of the ‘Pavilion of the Queen of Love and Beauty’ as ‘a galaxy of beauty and brilliancy’ (7), and James Nixon (1843) and Edward Courbould (1840) issued elaborate, highly idealized illustrations. However, not everyone was prepared to accept the deception, producing instead a satirical response. One of these was Peter Buchan’s droll travesty, The Eglinton Tournament and Gentleman Unmasked (1840), and parallel mockeries appeared elsewhere, including, some years later, a cartoon in Punch (1858). Most interesting, though, was Doyle’s visual skit. Responding to the hard realities as they were reported in the press – he did not witness the event first-hand – Doyle provides a withering take on the pageant, mocking its pretensions.

His first target in The Tournament is the incongruous mismatch between the idealism of courtliness and the inclemency of the weather (plate 1). Focusing on the opening procession, he shows the knights and their attendants progressing along a puddle-ridden pathway, with strafing lines of rain bearing down on them, a scene that should have been splendid but is simply wet and miserable. The contrast between how it was intended to appear and the reality is also conveyed in the opposition between the main scene and the frieze of minor figures placed above them. The top of the page represents knights and courtiers in various swaggering poses as they model their costumes and weapons, while those below are arranged in shivering groups with downcast faces.

Doyle’s take on the Eglinton Tournament, Left: Plate 1, showing the ruinous downpour; Right: Plate 2, vignettes showing the mock-knights in armour preparing for the event.

Funniest, though, is Doyle’s emphasis on the contrast between the medieval figures and their modern carriages and umbrellas. In making this juxtaposition he focuses the absurdity of the moment but makes a broader point about the incongruity of Victorians pretending to be figures of the Middle Ages while protecting themselves with contemporary devices. In his study of the debacle Ian Anstruther writes of the mismatch of the ‘knight and the umbrella,’ and Doyle satirizes by extension the whole medievalist project – suggesting the sheer silliness of historical reenactment and, by implication, all other sorts of aesthetic appropriation from the past. In other words, Doyle deploys a mock-heroic technique to ridicule the inflated claims of Gothic revivalism, bringing the modern and the old into comic mismatch. The effect is rather like a film depicting knights in armour in which a modern watch worn by an actor somehow escapes the cutting-room: laughs are inevitably generated, and where there should be high seriousness there is only anachronism and levity. Eglinton wanted his tournament to be taken seriously; Doyle reduces it to the level of burlesque.

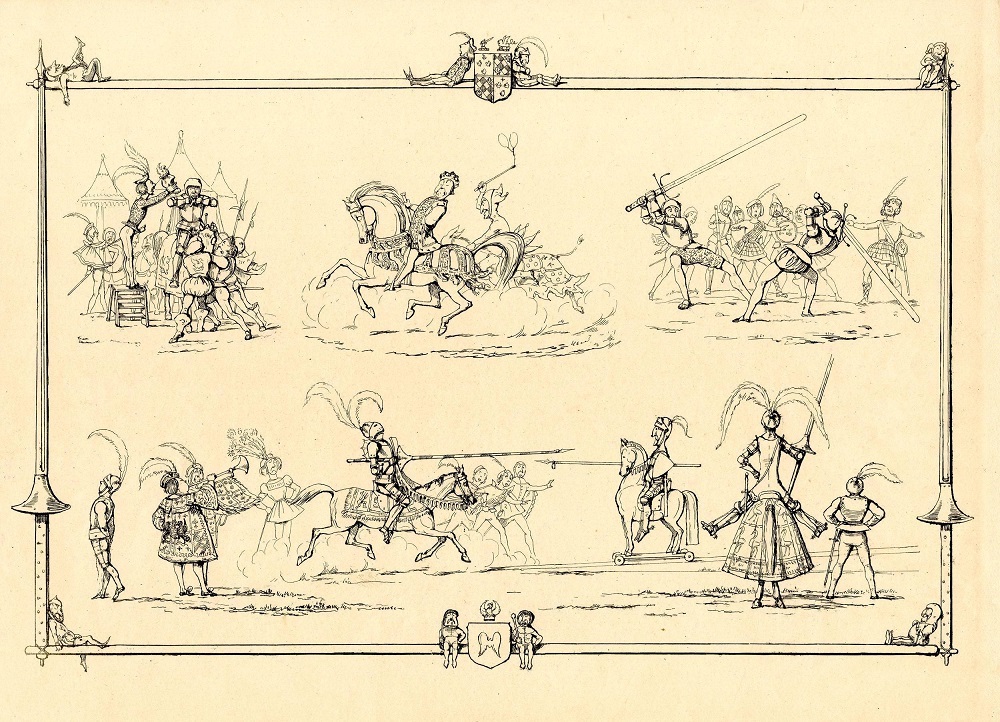

The poor weather was ready-made for comic exaggeration, but Doyle is equally concerned with other ridiculous aspects of the tournament. Knowing that the participants were trying to project a dignified version of the past, the artist suggests that what they are doing is really little more than a childish self-indulgence. Indeed, he juvenilizes the supposedly noble lords by endowing them with ridiculously over-large weapons (plates 2 & 3) as if they were literally children at play, accentuating the point in one vignette by placing a horse on wheels, converting it into a toy, and in another showing a knight struggling to sit on his mount. Dignity is drained away as Doyle reduces the tournament to the level of the nursery.

Left: Plate 3, some more practising; Right: Plate 4, one of the knightly skirmishes.

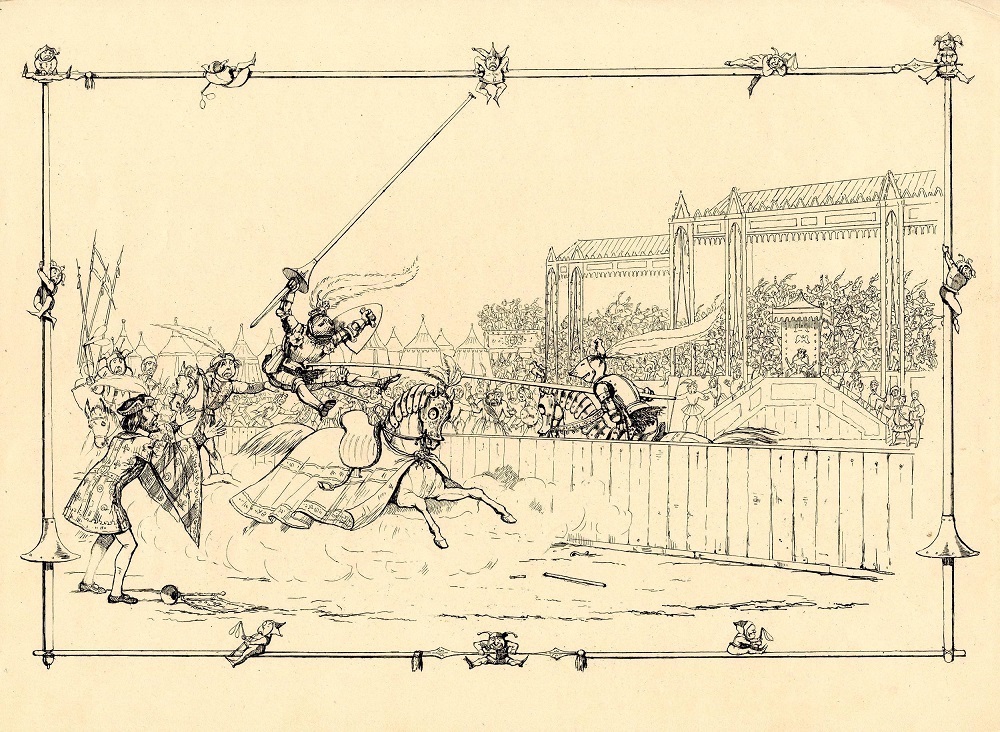

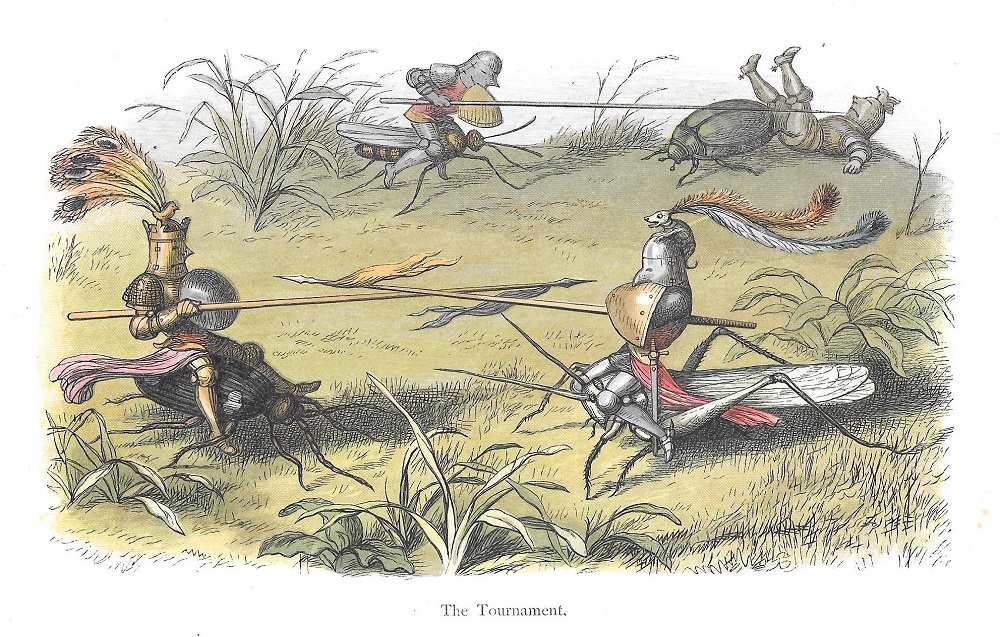

The formlessness of childish pretend is likewise evoked by Doyle’s visualization of the jousting and battles. In plates 4 and 5 he stresses the laughable incompetence of the participants by showing them falling from their horses or clinging desperately to their saddles and reins; the Eglinton Tournament was supposed to be a display of chivalric sword play and impressive charging through the lists, but Doyle highlights the fact that in practice it was a dangerous and inelegant show of tumbling and minor injuries – an effect at least acknowledged in contemporary literature. Once again, he counters the heroic with the anti–heroic, reminding the viewer that the tourney was only a pretence designed to impress. The Eglinton Tournament’s original spectators were simply disappointed by the shambles, and Doyle refigures that response for fireside viewers, invoking laughter where there should have been awe.

The satirizing of the event is mainly carried forward in this situational comedy. However, Doyle completes his comedic effects by deploying caricature in which he ridicules the pomposity and self-importance of the neo-medievalists by endowing them with arrogant faces and strutting postures. Having shown the aristocrats in ridiculous pretend fighting, he stresses their hauteur, creating another ironic contrast between what they do, which is ridiculous, and how they present themselves. The final plate (6) clinches this effect, depicting Lord Eglinton looking self-importantly from his steed as he presents a champion to ‘The Queen of Beauty,’ Lady Jane Georgiana Seymour, Duchess of Somerset. The expressions and attitudes suggest dignity, but the grandeur of the event is cancelled by her ladyship’s simpering face.

Left: Plate 5, The Tournament, with some disastrous effects; Right: Plate 6, presenting the winners to the Queen of Beauty.

Taking all of these comic strategies together, Doyle’s Tournament is an effective send-up mocking the behaviour of the upper-classes. It is in this sense social satire as much as commentary on a topical event, viewing the aristocracy in a remarkably undeferential way in a deferential age: where the apologists eulogize tradition with inaccurate claims of grandeur, Doyle shows the realities. Positioning himself as a bourgeois professional, he registers some of the contempt for the ‘higher ranks’ that would also be voiced by Charles Dickens and W. M. Thackeray in Bleak House (1853) and Vanity Fair (1847).

The Tournament as Parody

The Tournament mocks the debacle in Ayr, and Doyle stresses the absurdity of its pretend medievalism by satirising the archaic art of the Middle Ages. He does this by making his album into a pastiche version of an illuminated manuscript. Playing with the idea that marginal figures were a mode of commentary in early books, he frames his central images with mischievous characters, miniature knights and jesters; clinging to a border in the form of a lance, their behaviour is used to reflect and ridicule the main event.

In the opening design the characters shiver under umbrellas to amplify the experience of the main figures, yet most of the jesters in the subsequent pages are placed in ironic counterpoint to the event’s grandiosity. In the second scene, for instance, the fighting is undermined by the disparity between the centre and the borders: the knights are supposed to be impressive, but the marginal figures have fallen into a bored sleep. The pretensions of the melee (plate 4) are similarly reduced by the jesters’ toy-town fighting, and in the joust (plate 5) the fall of one of the contestants is mocked by the instability of the figures clinging to the lance as they fall and slip in echo of the knights’ perilous exchange. These small additions amplify the effect of the comedy – adding another dimension to the artist’s mock-heroic technique.

The Tournament and Doyle’s Development

The Tournament was one of several pieces of juvenilia. Others included Homer for the Holidays Jack the Giant Killer (1842, 1888). Each of these encapsulates Doyle’s artistic development as a precocious talent, and all of them establish the main outlines of his mature style.

Left: An illustration from Doyle’s book of 1842, Jack the Giant Killer, and Right: one of his cod-medieval designs for Thackeray’s Rebecca and Rowena (1850).

The Tournament anticipates these later developments in detail. Doyle’s fascination with pastiche medievalism prefigures his numerous humorous figures in Punch, and his mockery of medieval or neo-medieval art was further developed in his send-up of the paintings in the Westminster Hall Exhibition, Selections from the Rejected Cartoons (1848); his sharp eye for the distortions of an archaic style is also displayed in his illustrations for Thackeray’s dryly ironic (and very funny) reading of Scott’s Ivanhoe, Rebecca and Rowena (1850).

Social satire is likewise a main theme in Doyle’s art, and The Tournament’ fascination with ridiculous, ritualized behaviour became one of the artist’s mainstays. His representation of the upper-classes at play mutated into a central concern with the leisure of the bourgeoisie, a focus he very much extended in Manners and Customs of Ye Englyshe (1849) and Bird’s Eye Views of Society (1863–4).

Left: middle-class life in Bird’s Eye Views of Society (1864); and Right: ‘The Tournament’ in In Fairyland (1870).

Doyle’s burlesque tournament was similarly important as one of the first books to establish his characteristic vocabulary of motifs and compositions. The comedic treatment of the modern characters features throughout his art, and the miniature figures are part of his developing interest in fairies and ‘little people’ in general; tellingly, in his masterpiece, In Fairyland (1869–70), he clinches the linkage between the beginning and end of his career by showing the sprites engaged in a tournament. These are in the same manner as the miniature figures framing the pages in The Tournament, and such persona appear throughout his work.

Doyle’s satire also defines the artist’s fascination with processions of characters arranged in linear tableaux. His next published work, A Grand Historical Allegorical and Comical Procession of Remarkable Personages Ancient Modern and Unknown (1842) is the first development of The Tournament’s designs, and the same type of comedic frieze appears in An Overland Journey to the Great Exhibition(1851) and on the front cover of Punch (1849).

In short, The Tournament was Doyle’s foundational visual text. Technically accomplished, it opened a space that would be occupied by the artist for the duration of his long and inventive career.

Bibliography

Primary

Bird’s Eye Views of Society. London: Smith Elder, 1864.

A Grand Historical Allegorical Classical and Comical Procession of Remarkable Personages Ancient Modern and Unknown. London: McLean, 1842.

Homer for the Holidays. London: Pall Mall Gazette, 1887 [produced 1836].

In Fairyland. With a poem by William Allingham. London: Longman, 1870 [1869].

Jack the Giant Killer. London: Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1888 [produced 1842].

A Journal Kept by Richard Doyle in the Year 1840. With an introduction by J. Hungerford Pollen. London: Smith Elder, 1885.

Manners and Customs of Ye Englyshe. With text by Perceval Leigh.London: Bradbury & Evans [1849].

An Overland Journey to the Great Exhibition. London: Chapman & Hall, 1851.

Punch, 1843–50.

Selections from the Rejected Cartoons. London: McLean, 1848.

Thackeray, W. M. Rebecca and Rowena. London: Chapman & Hall, 1850.

The Tournament at Eglinton. London: Dickinson [1839].

Secondary

Aikman, Gordon. an Account of the Tournament at Eglinton. Edinburgh: Paton, 1839.

Anstruther, Ian. The Knight and the Umbrella: An Account of the Eglinton Tournament 1839. London: Godfrey Bles, 1963.

Buchan, Peter. The Eglinton Tournament and Gentleman Unmasked. London: Simpkin Marshall, 1840.

Corbould, Edward. The Eglinton Tournament. London: Hodgson & Graves, 1840.

Engen, Rodney. Richard Doyle .Stroud: The Catalpa Press, 1983.

Nixon, Henry James. The Eglinton Tournament. London: Colnaghi, 1843.

Stamp, Gavin. Anti-Ugly. London: Aurum, 2013.

Created 12 October 2023