he graphic satirist John Doyle (1797–1868) has been completely eclipsed by his son, the illustrator Richard, “Dicky” Doyle. However, in his own time Doyle père was regarded as an important contributor to the discourse of visual humour and political commentary. Signing himself ‘HB’ in order to maintain his anonymity, Doyle created a vast number of cartoons in the form of free-standing prints which mocked contemporary politics and current affairs. Published by Thomas McLean and sold in his shop, these images were produced on a weekly or fortnightly basis. Typically issued in threes, which gave consumers the opportunity to choose a favourite at one visit to the printseller, they appeared in the years from 1825 to 1850, and made use of the new medium of lithography, which was invented by Senefelder in 1796. This process made the designs much easier to produce than a wood engraving or etching on copper.

Doyle, an Irishman from Dublin, had earlier tried to make a career as a portraitist and equestrian artist, but only found success, having moved to London from Ireland in the years around 1822, in the print-trade (Engen 12–14). Here earned a good living as an insightful commentator on the often turbulent politics of the age. Though sometimes poorly and rapidly drawn as he struggled to cope with the punishing deadlines, his political ‘drawings’ provided a near-immediate playback on the events, policies and politicians of the day, and attracted a large and appreciative audience. In all, he produced about a thousand prints and the mysterious initials ‘H B’ – which were formed by fusing the ‘J’ and ‘D’ of Doyle’s name – became a ‘household phenomena’ (Engen 13).

His particular qualities, as noted by Victorian critics, were two-fold. He was widely admired, as Graham Everitt remarks, for the ‘excellence of his likenesses’ (275). In an age long before television or film, Doyle offered highly realistic and accurate portraits of the leading political figures, enabling his audience to visualize Daniel O’Connell, Lord John Russell, Wellington, Peel, Brougham and other parliamentarians. Indeed, he studied his subjects in the flesh and became, his obituarist notes, a ‘quiet … unsuspected frequenter of the lobby and gallery’ (47), making sketches of the MPs and ministers as they conducted parliamentary business in Westminster Hall and, after 1837, in Pugin’s new Houses of Parliament. The quality of his portraiture led to many of HB’s drawings being acquired, as true representations, a record of the age, by the National Portrait Gallery in London.

Yet the ‘wonderful truthfulness of his living likenesses’ (47) was only part of Doyle’s appeal. The artist was especially adept at finding humorous ways with which to ridicule an issue or a politician’s behaviour. Sometimes it was simply a matter of illustrating a conversation between political rivals, animating their interaction by including speech-bubbles. More often, Doyle employed bizarre comedic situations, literary or pictorial allusiveness, or a weird zoomorphism. Each of these satirical strategies was used to make an ironic or sarcastic judgment on the issues of the week.

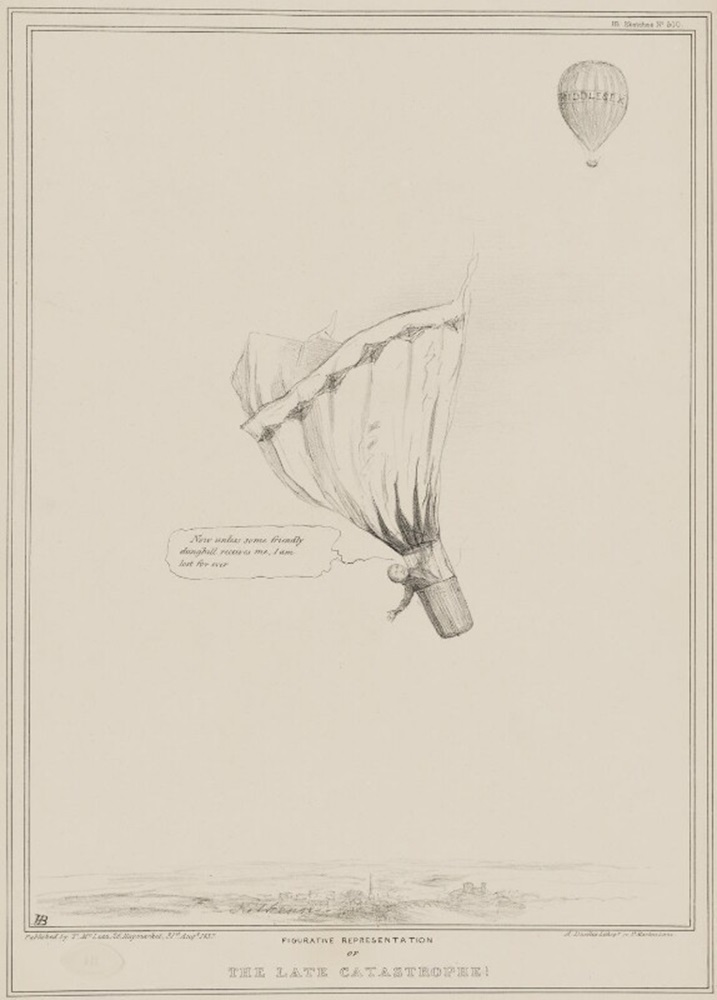

Figurative representation of the late catastrophe! [sic] (31 August 1837) is a good example of Doyle’s capacity to devise a situation which though absurd and incongruous is a powerful, metaphorical representation of a topical event. It shows the MP Joseph Hume about to fall from the sky in a deflating balloon, the visual sign of the collapse of his high-flying career when he his original seat in the 1837 election, although he was able to take up a new constituency in Kilkenny, Ireland. This was far from his ideal and is identified as a ‘dung hill’ in the character’s speech bubble; though an Irish Catholic and at least interested in the reforming arguments of Daniel O’Connell, Doyle plays to English prejudices. Hume’s falling from political grace is cleverly embodied in the notion of a literal fall, and the artist adds another layer of topical implication by referencing the recent exhibition of the ‘Great Nassau,’ a huge balloon that was tethered in Vauxhall Gardens.

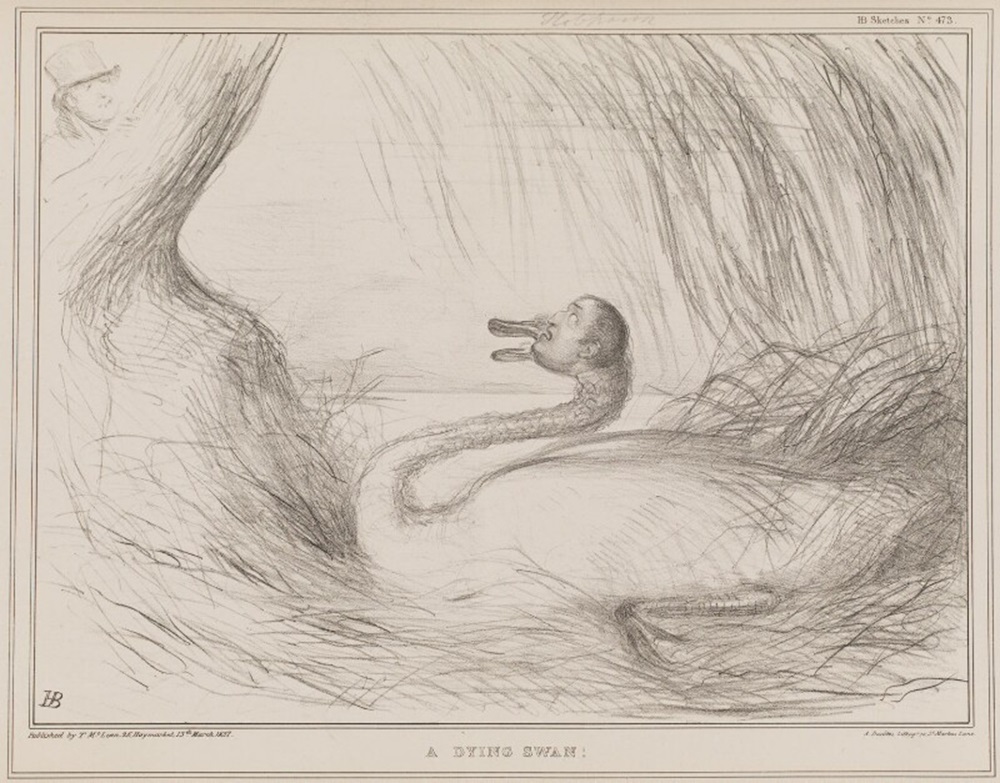

Equally effective is Doyle’s use of animal-imagery to act as a representation of an event, or to comment on politicians’ interests or moral character. His bestiary is a strange display, a sort of visual Aesop, with members of the political parties being characterized as sheep, horses, dogs, cats and even rats, deploying an imagery that parallels the art the French satirist, J. J. Grandville. For example, the pretentions of John Cam Hobhouse (Baron Broughton de Gyfford) are satirized in A Dying Swan (13 March 1837): Hobhouse’s influence on government was fading, and Doyle shows him, grotesquely, in a zoomorphic conjunction of the politician’s closely observed portrait and the swan’s body; John Peel looks on indifferently. In The Great Moth (1 July 1840), likewise, the artist fuses a likeness with an animal’s body, creating an effect both ridiculous and unsettling. In this print Doyle travesties Sir Frederick William Trench’s obsession with finding an adequate way to illuminate the Commons, a preoccupation Doyle satirizes as a pointless endeavour. Accordingly, he characterizes Trench as a brainless moth, drawn to a Bude lamp, a type designed for maximum brightness. The image asks a couple of simple questions: do the public want an MP to spend his time doing something so trivial? And is Trench really as stupid as a moth? Doyle’s posing of the inquiry is damning; such shrewdness was typical of his clear-sighted analyses.

Satirical prints by John Doyle. Left: Figurative representation of the late Catastrophe! (1837). Right: The Great Moth (1840).

Indeed, all such visual strategies project the primary aims of graphic satire as a means to attack abuses through the application of a dislocating, challenging humour. Doyle was of course only one voice in a tradition of caricature and cartooning which developed in the eighteenth century in the work of James Gillray, Thomas Rowlandson and George Woodward. Like these designers, Doyle used visual conceits to express his critiques. However, he differed from these earlier practitioners insofar as he never used obscenity, extreme distortions of facial features or any of the bad taste that was so much a part, especially, of the outrageously vulgar (and sometimes pornographic) designs of Gillray. Rather, he catered for a more refined clientele, and is widely regarded, as his grandson Arthur Conan Doyle remarked, as the ‘father of polite caricature … drawing gentlemen for gentlemen’ (7), creating an art, George Williamson insists, that was always ‘marked by reticence, courtesy, and a sense of good breeding’ (Catholic Encyclopaedia).

Doyle’s zoomorphism Left: A Dying Swan (1837). Right: The Harpies attacking the daughters of Pandarus (1848).

Both Conan Doyle and Williamson probably overstate their case – it is hardly moderate, for example, to depict a politician as an farm animal, a dog, or an insect – but there is no doubt Doyle’s work is a sort of bridge between the anarchic rudeness of the eighteenth century and the development of ‘good taste’ and ‘gentlemanliness’ in the Victorian ‘age of improvement.’ W. M. Thackeray thought the humour too restrained, an emollient only good enough to raise a smile but rarely a laugh (19); nevertheless, H. B. defined a new direction for graphic satire that was taken up by the cartoonists of Punch, the situational comedy of John Leech and John Tenniel, and in the droll, wistful reflections of his more famous son, “Dicky” Doyle.

Left: Doyle’s zoomorphism in the grey tone of lithography in his send-up of O’Connell in An Extraordinary Animal (1835). Right: Gillray’s famous image of Wellington and Napoleon carving up the world in his hand-coloured etching, The Plum-Pudding in Danger (1805; from the library of Congress image, reproduction no. LC-USZC4-8791, in the public domain).

Bibliography

Note: All Doyle prints are taken from the collection of the National Portrait Gallery, London, and are reproduced with permission.

Conan Doyle, Arthur. Memories and Adventures. 1924; rpt. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Engen, Rodney. Richard Doyle. Stroud: The Catalpa Press, 1983.

Everitt, Graham. English Caricaturists. London: Swan Sonneschein, 1893

‘Obituary; John Doyle.’Art Journal 30 (March 1868).

Thackeray, W. M. An Essay on the Genius of George Cruikshank. London: Hooper. 1840.

Williamson, George. ‘John Doyle.’ Catholic Encyclopaedia.. Online edition.

Created 3 November 2023