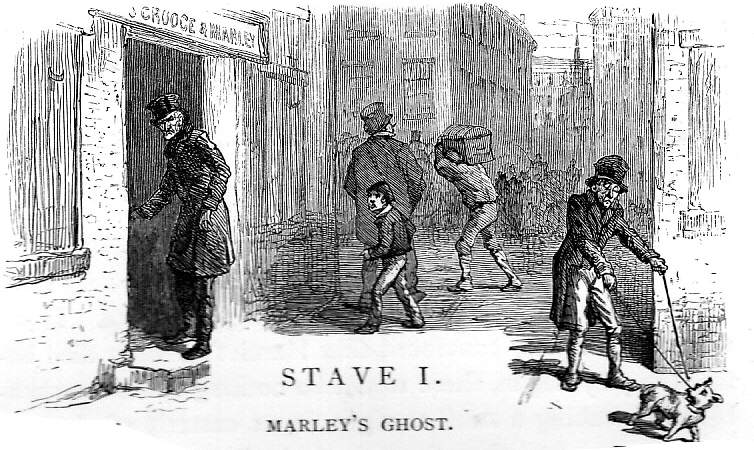

"Scrooge and Marley's," vignette for "Stave I. Marley's Ghost" by Sol Eytinge, Jr. 1870. 5.5 cm high by 9.4 cm wide. The second regular plate for the Diamond Edition of Dickens's A Christmas Carol in Prose: being a ghost story of Christmas (Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1869), top, page 11. Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Scrooge, although a denizen of one of Europe's largest cities, is unaware of the teeming urban life all around him as he pauses at the door of his counting-house, scowling at the reader. Whereas recent film adaptations have established the story's setting by superimposing the dome of St. Paul's Cathedral on the skyline, Eytinge has chosen to place a Wren city church in the distance, an edifice not unlike places of worship with which he would have been familiar, the spired churches of New England. Even at Christmas, the miser leads an "oyster-like" capitalist existence utterly alienated from the essential Christian message of universal brotherhood which the distant spire represents. The juxtaposition of a blind man and his dog is a naturalistic detail that may also be taken as a comment on the emotionally insensitive Scrooge's being without friend, companion, family, or even a pet. Eytinge depicts aged Ebenezer Scrooge as a well-dressed bourgeoisie in top hat and great coat, in contrast to the street boy and porter in his shirt sleeves in the middle of the street. Eytinge has given the sign "Scrooge & Marley" a place of prominence above the proprietor's head, pointing towards the passage in which the narrator comments upon the fact that the surviving business partner has never bothered to have Old Marley's name above the warehouse door painted out. His office building is closed up, its windows on either side of the entrance shuttered to exclude the light of day and the hubbub of surrounding humanity. The passage realized is perhaps this, since Eytinge has placed a blind man and his little dog, scurrying out of the way, in the foreground, right:

Even the blindmen's dogs appeared to know him; and when they saw him coming on, would tug their owners into doorways and up courts; and then would wag their tails as though they said, "no eye at all is better than an evil eye, dark master!"

But what did Scrooge care? It was the very thing he liked. To edge his way along the crowded paths of life, warning all human sympathy to keep its distance, was what the knowing ones call "nuts" to Scrooge. [Stave One, "Marley's Ghost"]

Bibliography

Dickens, Charles. A Christmas Carol in Prose: being a ghost story of Christmas, il. Sol Eytinge, Junior. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1869.

Last modified 25 December 2010