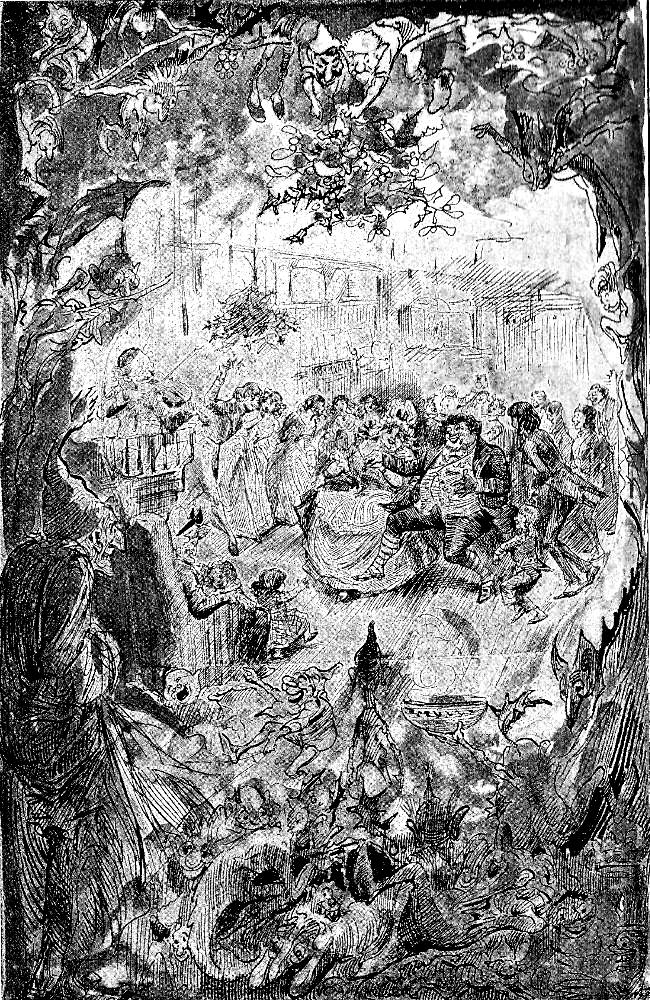

"Christmas Eve at Old Fezziwig's" by Charles Green (59). 1912. 7.9 x 10.4 cm, vignetted. Dickens's A Christmas Carol, Pears Centenary Edition, in which the plates often have captions that are different from the titles in the "List of Illustrations" (15-16). Specifically, Christmas Eve at Old Fezziwig's has a caption that is quite different from its title in the "List of Illustrations"; the textual quotation that serves as the caption for this illustration of the mercantile couple's greeting departing business associates and employees as members of an extended family is "Mr. and Mrs. Fezziwig took their stations, one on either side the door, and, shaking hands with every person individually as he or she went out, wished him or her a Merry Christmas" (59, verbatim from the centre of the facing page) in "Stave Two, The First of the Three Spirits."

Context of the Illustration

But if they had been twice as many — ah, four times — old Fezziwig would have been a match for them, and so would Mrs Fezziwig. As to her, she was worthy to be his partner in every sense of the term. If that's not high praise, tell me higher, and I'll use it. A positive light appeared to issue from Fezziwig's calves. They shone in every part of the dance like moons. You couldn't have predicted, at any given time, what would have become of them next. And when old Fezziwig and Mrs Fezziwig had gone all through the dance; advance and retire, both hands to your partner, bow and curtsey, corkscrew, thread-the-needle, and back again to your place; Fezziwig cut — cut so deftly, that he appeared to wink with his legs, and came upon his feet again without a stagger.

When the clock struck eleven, this domestic ball broke up. Mr. and Mrs. Fezziwig took their stations, one on either side of the door, and shaking hands with every person individually as he or she went out, wished him or her a Merry Christmas. When everybody had retired but the two prentices, they did the same to them; and thus the cheerful voices died away, and the lads were left to their beds; which were under a counter in the back-shop.

During the whole of this time, Scrooge had acted like a man out of his wits. His heart and soul were in the scene, and with his former self. He corroborated everything, remembered everything, enjoyed everything, and underwent the strangest agitation. It was not until now, when the bright faces of his former self and Dick were turned from them, that he remembered the Ghost, and became conscious that it was looking full upon him, while the light upon its head burnt very clear.

"A small matter," said the Ghost, "to make these silly folks so full of gratitude."

"Small!" echoed Scrooge.

The Spirit signed to him to listen to the two apprentices, who were pouring out their hearts in praise of Fezziwig: and when he had done so, said,

"Why! Is it not! He has spent but a few pounds of your mortal money: three or four perhaps. Is that so much that he deserves this praise?"

"It isn't that," said Scrooge, heated by the remark, and speaking unconsciously like his former, not his latter, self. "It isn't that, Spirit. He has the power to render us happy or unhappy; to make our service light or burdensome; a pleasure or a toil. Say that his power lies in words and looks; in things so slight and insignificant that it is impossible to add and count them up: what then? The happiness he gives, is quite as great as if it cost a fortune." ["Stave Two: The First of the Three Spirits," 58-60: the original caption has been emphasized.]

Commentary: "A Remembrance of Business Relationships Past"

Although there is no equivalent illustration in the 1843 first edition of the novella, or later editions, many illustrators have emulated the Christmas Book's first illustrator, John Leech in focussing on the joyful country dance, "Sir Roger de Coverley," in which frontispiece (see below) the Fezziwigs take the lead in the midst of swirling, Baroque action. By the turn of the century, such a Christmas entertainment thrown by the employers for their many associates and employees must have seemed quaint; Green focusses not on the exuberant dance scene, but on the Fezziwigs at the close of the festivities serving as host and hostess at a much-valued (and, Green implies, by his era, much-missed community rite).

Although Dickens undoubtedly concurred with Leech that, for the original edition, the image of the Fezziwigs' ball in the warehouse — transformed for the Christmas party with seasonal greenery and in particular that rather obvious fertility symbol, mistletoe — would make a fitting induction to the nostalgic novella comparing Christmasses past with Christmas present, Green has chosen instead to explore the social ramifications of what we today might term "The Christmas Office Party." Were we to apply such a term to the Fezziwigs' Ball we would be missing the implication that the mercantile couple in this Christmas tale for the Industrial Age have replaced the local squire and his lady as parents to the extended family of the village, traditional albeit paternalistic figures associated with the country celebration of Christmas in Washington Irving's Bracebridge Hall, written by the American humourist when he was visiting England in 1821 and published in 1822 under the pseudonym "Geoffrey Crayon." Dickens substitues a London warehouse for Irving's Ashton Hall, near Birmingham, in the Regency period.

Sol Eytinge, Junior, in his twenty-fifth anniversary Christmas Carol,published to mark Dickens's copyright agreement with Boston's Ticknor and Fields, seems to have been the first illustrator to consider the impact of Scrooge's earlier experiences on his character as a miser, beginning with the deserted schoolroom scene, The Vision of Ali Baba, the vignette at the head of "Stave 2. The First of the Three Spirits," but continuing with the visual exemplum of what a good employer ("a good man and master") should be, The Fezziwig Ball (see below), in which the company delight in their employer's nimbly "cutting the rug" on the bare planks of the warehouse while young Master Fezziwig attempts to emulate his father (lower right). As in the Leech original, young and old have honoured places at the community festival. American Household Edition illustrator A. E. Abbey likewise celebrates the dance, but places the employers to one side in Old Fezziwig, clapping his hands to stop the dance, cried out, "Well done!" (see below) in order to communicate the couple's enjoying seeing their employees making merry in exchange for just "a few pounds of . . . mortal money." By implication, Scrooge and his fiancé are leading off the country dance (centre). On the other hand, neither the other Household Edition illustrator, Fred Barnard, nor the Charles Dickens Library Edition (1910) illustrator Harry Furniss realises any of these telling scenes from Scrooge's young adulthood.

In Green's treatment of the close of the party, guests, getting ready to depart (as signalled by their donning capes and great-coats), shake the hands of their hosts: the ladies wait their turn to exchange a parting word with Mrs., Fezziwig (left, in traditional eighteenth-century gown and head-covering), while to the right, Old Fezziwig warmly shakes the hand of a departing gentleman, holding his beaver hat. While the short-haired young businessman thus greeted wears stovepipe trousers of the fashion introduced by that Regency arbiter of fashion Beau Brummel, Fezziwig wears the tailcoat, stockings, breeches, and wig that were the fashion of the previous generation. In contrast to the bonhomie and energy of other illustrators' dance scenes, Green's scene of departure is low-key, close-up, and intimate.

Relevant Illustrations from the 1843, 1868, and 1910 Editions

Left: Eytinge's 1868 interpretation of Fezziwig's dance moves, The Fezziwig Ball. Centre: Leech's 1843 interpretation of the country dance in the urban warehouse, Mr. Fezziwig's Ball. Right: Furniss's lively reinterpretation of the employees' dance, The Fezziwig's Ball (1912).

Above: Abbey's reinterpretation of the same dance scene, Old Fezziwig, clapping his hands to stop the dance, cried out, "Well done!" (1876).

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Illustrations for A Christmas Carol (1843-1915)

- John Leech's original 1843 series of eight engravings for Dickens's A Christmas Carol

- Sol Eytinge, Junior's 1867-68 illustrations for two Ticknor & Fields editions for Dickens's A Christmas Carol

- E. A. Abbey's 1876 illustrations for The American Household Edition of Dickens's Christmas Books

- Fred Barnard's 1878 illustrations for The Household Edition of Dickens's Christmas Books

- Charles E. Brock's 1905 illustrations for A Christmas Carol and The Chimes

- A. A. Dixon's 1906 Collins Pocket Edition for Dickens's Christmas Books

- Harry Furniss's 1910 Charles Dickens Library Edition of Dickens's Christmas Books

- A selection of Arthur Rackham's 1915 illustrations for Dickens's A Christmas Carol

Bibliography

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Junior. Diamond Edition. 14 vols. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

_____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1878. Vol. XVII.

_____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by A. A. Dixon. London & Glasgow: Collins' Clear-Type Press, 1906.

_____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. VIII.

_____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by A. A. Dixon. London & Glasgow: Collins' Clear-Type Press, 1906.

_____. A Christmas Carol in Prose, Being a Ghost Story of Christmas. Illustrated by John Leech. London: Chapman and Hall, 1843.

_____. A Christmas Carol in Prose: Being a Ghost Story of Christmas. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1868.

_____. A Christmas Carol in Prose, Being A Ghost Story of Christmas. Illustrated by John Leech. (1843). Rpt. in Charles Dickens's Christmas Books, ed. Michael Slater. Hardmondsworth: Penguin, 1971, rpt. 1978.

____. A Christmas Carol and The Cricket on the Hearth. Illustrated by Charles Edmund Brock. London: J. M. Dent, and New York: Dutton, 1905, rpt. 1963.

_____. A Christmas Carol. Illustrated by Charles Green, R. I. London: A & F Pears, 1912.

_____. A Christmas Carol. Illustrated by Arthur Rackham. London: William Heinemann, 1915.

_____. Christmas Stories. Illustrated by E. A. Abbey. The Household Edition. 16 vols. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876.

Created 6 August 2015

Last modified 4 March 2020