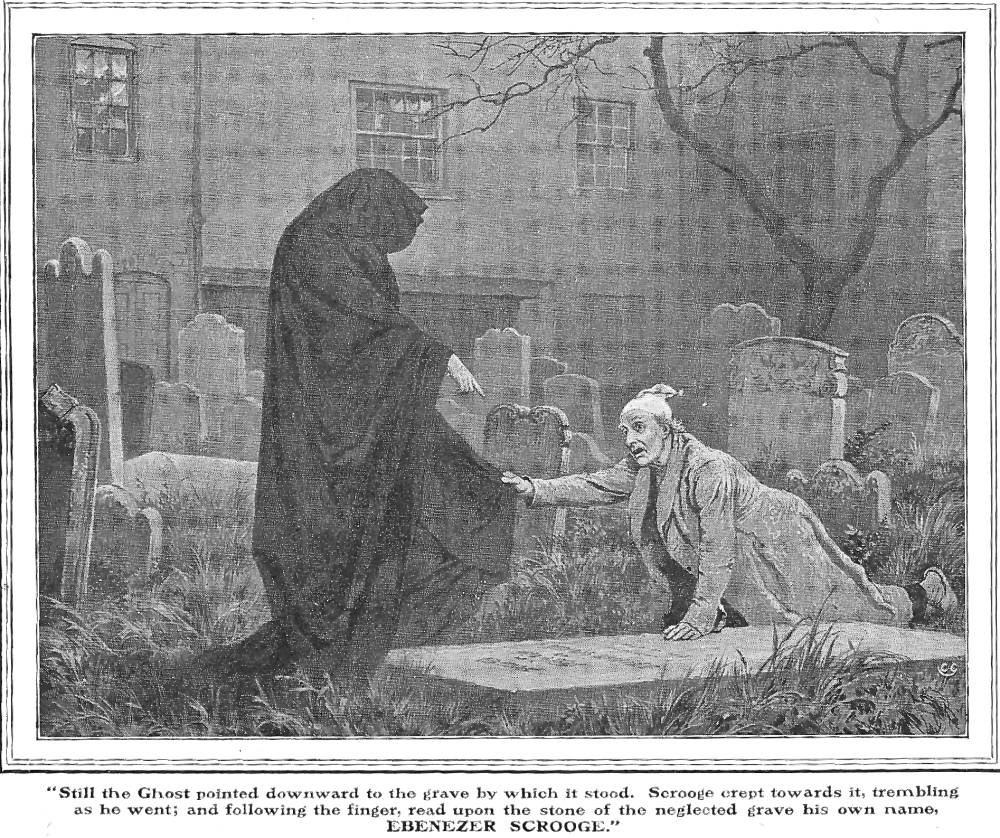

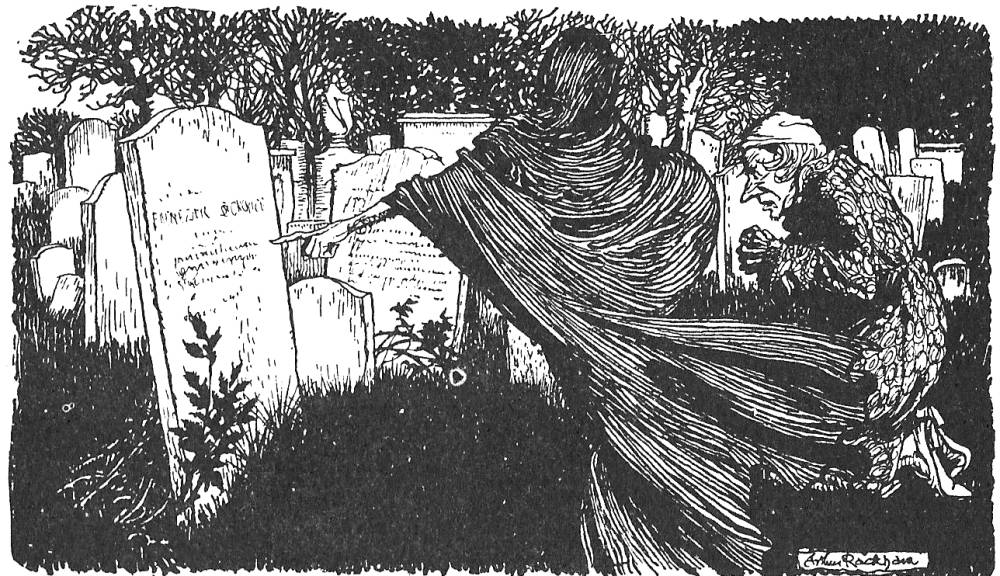

"Scrooge and the Third Spirit" by Charles Green (125). 1912. 11 x 14.6 cm, framed. Dickens's A Christmas Carol, Pears Centenary Edition, in which the plates often have captions that are different from the titles in the "List of Illustrations" (p. 15-16). Specifically, Scrooge and the Third Spirit has a caption that is quite different from the title given in the "List of Illustrations"; the textual quotation that serves as the caption for this illustration of the terrifying moment when Scrooge discovers his own untended grave is "Still the Ghost pointed downward to the grave by which it stood. Scrooge crept towards it, trembling as he went: and following the finger, read upon the stone of the neglected grave his own name, EBENEZER SCROOGE" (124, adapted from the bottom of the page facing the full-page lithograph) in "Stave Four, The Last of the Spirits." The model that John Leech provided later illustrators in the 1843 first edition of the novella, is exceptionally well known — indeed, after Oliver's Asking for More by George Cruikhank it may well be one of the best-known illustrations from the Victorian period. In later editions, a number of illustrators have included such a scene, notably Sol Eytinge, Jr., focussing on Scrooge's terror, In the churchyard (see below). However, as a British artist Charles Green simply may not have had access to a volume published across the Atlantic; Green, however, would have had access to a more immediate visual resource: Harry Furniss's The Last of the Spirits (see below) in the Charles Dickens Library Edition (1910).

Context of the Illustration

The Phantom pointed as before.

He joined it once again, and wondering why and whither he had gone, accompanied it until they reached an iron gate. He paused to look round before entering.

A churchyard. Here, then, the wretched man whose name he had now to learn, lay underneath the ground. It was a worthy place. Walled in by houses; overrun by grass and weeds, the growth of vegetation's death, not life; choked up with too much burying; fat with repleted appetite. A worthy place!

The Spirit stood among the graves, and pointed down to One. He advanced towards it trembling. The Phantom was exactly as it had been, but he dreaded that he saw new meaning in its solemn shape.

"Before I draw nearer to that stone to which you point," said Scrooge, "answer me one question. Are these the shadows of the things that Will be, or are they shadows of things that May be, only?"

Still the Ghost pointed downward to the grave by which it stood.

"Men's courses will foreshadow certain ends, to which, if persevered in, they must lead," said Scrooge. "But if the courses be departed from, the ends will change. Say it is thus with what you show me."

The Spirit was immovable as ever.

Scrooge crept towards it, trembling as he went; and following the finger, read upon the stone of the neglected grave his own name, EBENEZER SCROOGE.

"Am I that man who lay upon the bed?" he cried, upon his knees.

The finger pointed from the grave to him, and back again.

"No, Spirit! Oh no, no!"

The finger still was there.

"Spirit!" he cried, tight clutching at its robe, "hear me. I am not the man I was. I will not be the man I must have been but for this intercourse. Why show me this, if I am past all hope?"

For the first time the hand appeared to shake. ["Stave Four: The Last of the Spirits," 124-126]

Commentary: "Epiphany in the Churchyard"

Right: The Last of the Spirits by Leech.

Since Dickens tended to derive inspiration from his illustrators' work as they derived inspiration from his, the text and the accompanying illustration The Last of the Spirits (see right) together form a climax in the story of Scrooge's spiritual and moral epiphany; the third dimension of his reclamation, the social, is completed in the textual scenes in the fifth and final stave, "The End of It," and in the Leech tailpiece, Scrooge and Bob Catchit. The visual tradition of the seventh Leech illustration is not represented in either Household Edition, the American by E. A. Abbey and the British by Fred Barnard, but is well represented in the illustrated editions by Sol Eytinge, Jr., Harry Furniss, and Arthur Rackham. Since the source and inspiration for most if not all post-1843 illustrations of the churchyard scene are likely the Leech illustration, it is worthwhile to see what changes the realist Green wrought upon Leech's iconic interpretation for the Hungry Forties.

As Paul Davis notes in The Lives and Times of Ebenezer Scrooge,

Dickens considered his art "an imitation of the ways of Providence," and he wanted his Christmas story to transform the life of its reader in the way the spirits transform Scrooge's life. . . . One of the pleasures these novels [of the period, including the Carol] offered to their Victorian readers derived from attuning oneself to perceive the mundane infused with spiritual truth. Though Ruskin and a few others could not see through the "naturalism" of the Carol to its supernatural level, many more Victorians were moved by its spiritual power. [62]

In this Bunyanesque "Miser's Progress," the trajectory (if Scrooge does not reform) is towards this untended, unfriended grave; but, if he reforms, Scrooge will be reborn, becoming a child again in his delight at all things Christmas. Dickens's description of this welcome epiphany from miser to philanthropist is all the more effective because of the illustration's highlighting Scrooge's confronting his own mortality in an overgrown London churchyard in a pitch black night before Scrooge throws open the curtains on a 'bright and cold Christmas morning, and conducts negotiations with Mrs. Dilber and the street boy in the new spirit of St. Ebenezer.

Although the general compositions of the 1843 and 1912 illustrations are similar, working in the new medium of lithography, Green exploits the horizontal orientation that the larger page in the Pears editions of The Christmas Books made available to him. Working in a strictly vertical orientation, Leech has a tight focus requiring that Scrooge's posture be vertical; he does not sprawl across his grave, as in the 1912 illustration. His posture is suggestive of utter despair, his hands before his face, as he kneels upon his grave, although the lettering on the tombstone in the centre faces the reader rather than Scrooge. In fact, in Green's plate, we can barely make out the inscription, which logically faces Scrooge — but then it does need to, for the text in block capitals announces clearly whose grave it is. The atmosphere in this hand-tinted engraving is communicated by the deep blues and greens which contrast the spirit and the churchyard vegetation with Scrooge in his nightgown. Leech's plate is dynamic: the movement is largely upward and downward on the vertical axis, whereas in Green's the motion is both horizontal, with a petitioning Scrooge over an extended tombstone, and vertical, with two limbs of the tree (right) reaching up and the spirit, whose head is higher than the highest headstone (left), pointing diagonally down. In the Green lithograph, which possesses black-and-white photographic realism, the figures are organized into a pyramid in which the Spirit's head is the apex and the tombstone the base. Whereas Leech had included tenements across the street (right rear) to suggest an atmosphere of urban decay, Green develops the light-walled church into a substantial backdrop, with six windows and doors, as a contrast to the black-shrouded Spirit of Christmas Yet to Come. Against these static features, the building and the wilderness of headstones, Green has placed the two kinetic figures, the pointing Spirit and the desperate, prostrate Scrooge, begging for another chance to engage positively with humanity and become an active participant in the brotherhood of the living.

Related Illustrations from Other Editions, 1868-1910

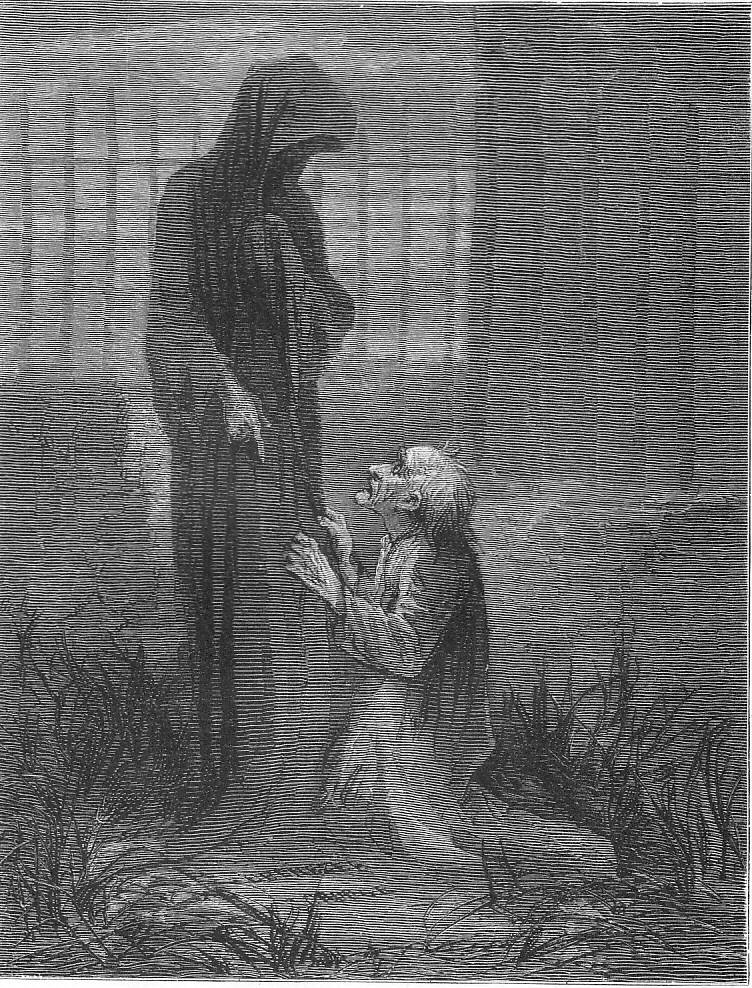

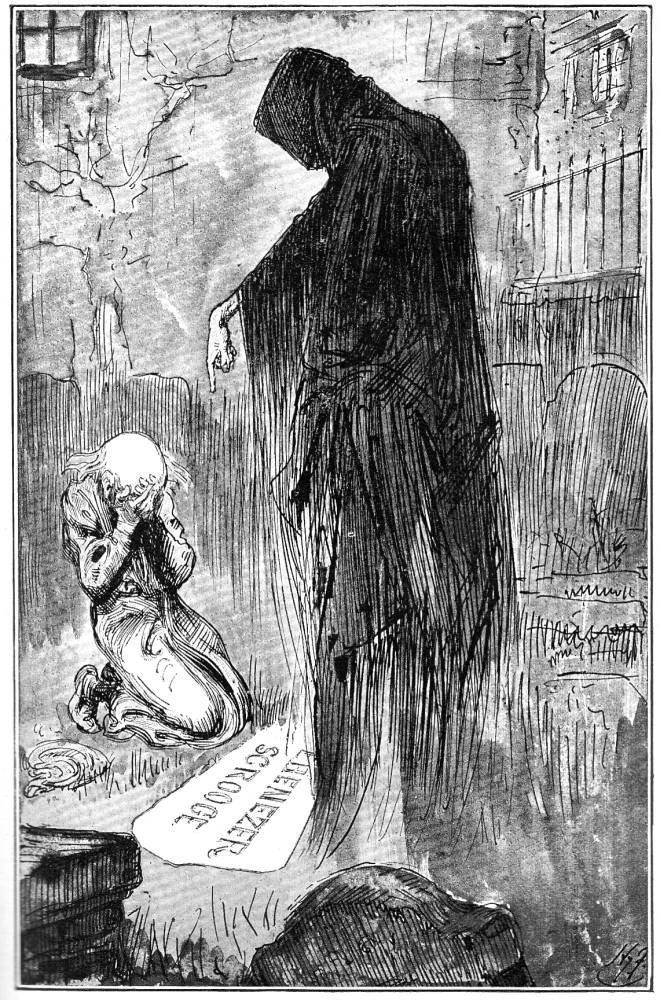

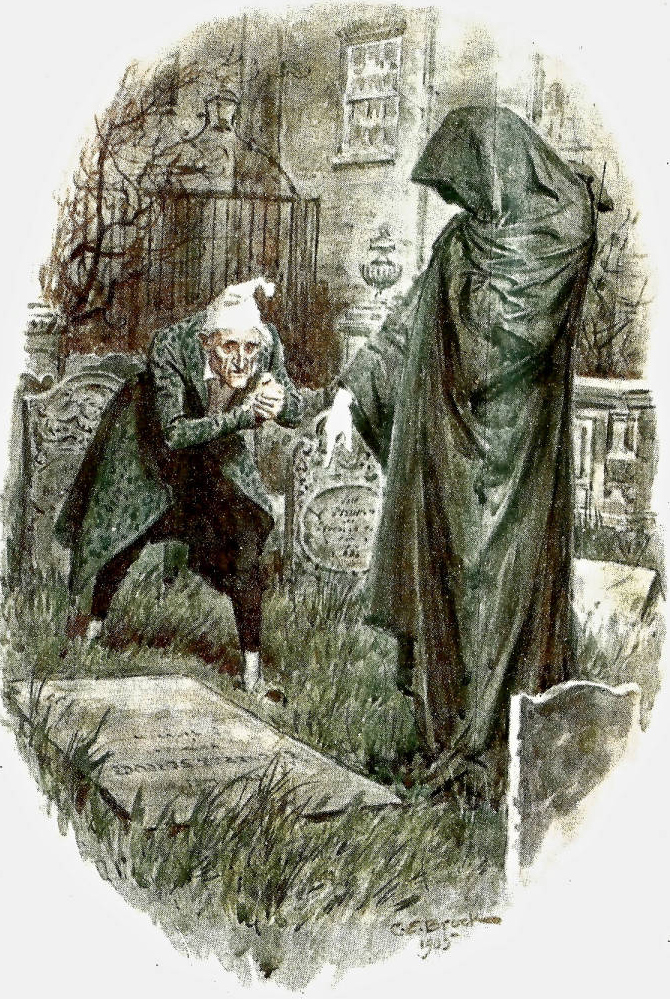

Left: Eytinge's "In the Churchyard" (1868); centre: Furniss's's "The Last of the Spirits" (1910); right: Charles E. Brock's illustration focuses on Scrooge's reaction in Scrooge crept towards it, trembling as he went (1905).

Above: Arthur Rackham's's preparing the reader for the famous scene in the graveyard, Heading to Stave Four (1915).

Illustrations for A Christmas Carol (1843-1915)

- John Leech's original 1843 series of eight engravings for Dickens's A Christmas Carol

- Sol Eytinge, Junior's 1867-68 illustrations for two Ticknor & Fields editions for Dickens's A Christmas Carol

- E. A. Abbey's 1876 illustrations for The American Household Edition of Dickens's Christmas Books

- Fred Barnard's 1878 illustrations for The Household Edition of Dickens's Christmas Books

- Charles E. Brock's 1905 illustrations for A Christmas Carol and The Chimes

- A. A. Dixon's 1906 Collins Pocket Edition for Dickens's Christmas Books

- Harry Furniss's 1910 Charles Dickens Library Edition of Dickens's Christmas Books

- A selection of Arthur Rackham's 1915 illustrations for Dickens's A Christmas Carol

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.[You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Checkmark and Facts On File, 1999.

Davis, Paul. The Lives and Times of Ebenezer Scrooge. New Haven: Yale UP, 1990.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Junior. Diamond Edition. 14 vols. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

_____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1878. Vol. XVII.

_____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by A. A. Dixon. London & Glasgow: Collins' Clear-Type Press, 1906.

_____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. VIII.

_____. A Christmas Carol in Prose, Being a Ghost Story of Christmas. Illustrated by John Leech. London: Chapman and Hall, 1843.

_____. A Christmas Carol in Prose: Being a Ghost Story of Christmas. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1868.

_____. A Christmas Carol in Prose, Being A Ghost Story of Christmas. Illustrated by John Leech. (1843). Rpt. in Charles Dickens's Christmas Books, ed. Michael Slater. Hardmondsworth: Penguin, 1971, rpt. 1978.

____. A Christmas Carol and The Cricket on the Hearth. Illustrated by Charles Edmund Brock. London: J. M. Dent, and New York: Dutton, 1905, rpt. 1963.

_____. A Christmas Carol. Illustrated by Charles Green, R. I. London: A & F Pears, 1912.

_____. A Christmas Carol. Illustrated by Arthur Rackham. London: William Heinemann, 1915.

_____. Christmas Stories. Illustrated by E. A. Abbey. The Household Edition. 16 vols. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876.

Created 28 August 2015

Last modified 11 March 2020