Dr. Jeddler and Marion's Birthday

Charles Green

1912

9.4 x 7.3 cm, vignetted

Dickens's The Battle of Life, The Pears' Centenary Edition, IV, 23.

[Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[Victorian Web Home —> Visual Arts —> Illustration —> Charles Green —> The Battle of Life —> Charles Dickens —> Next]

Dr. Jeddler and Marion's Birthday

Charles Green

1912

9.4 x 7.3 cm, vignetted

Dickens's The Battle of Life, The Pears' Centenary Edition, IV, 23.

[Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

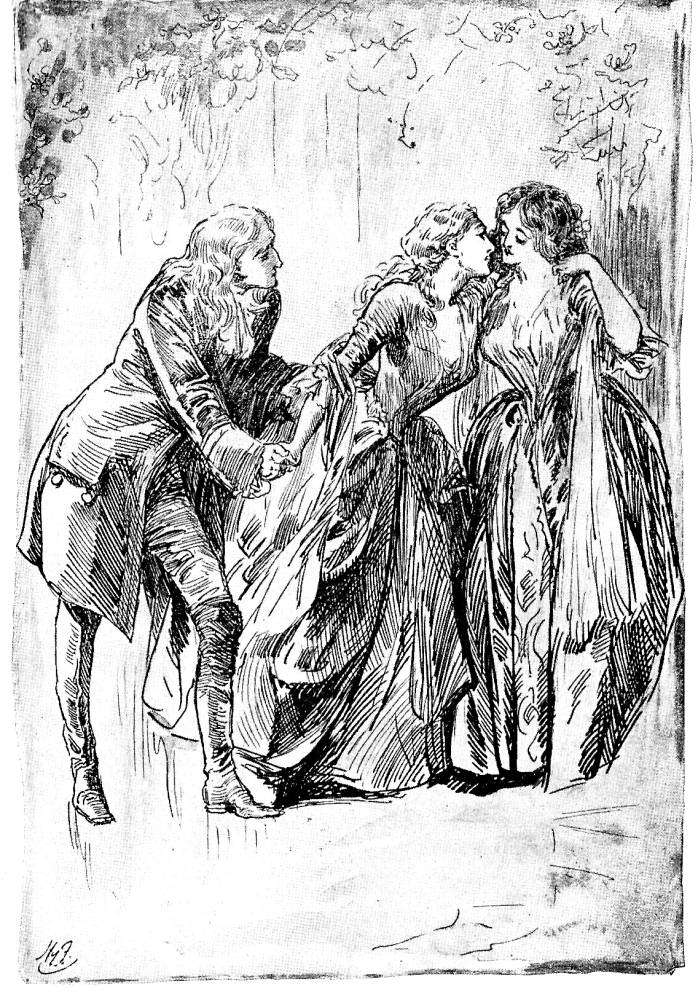

Green's picture of Dr. Jeddler and his teenaged daughters in the orchard on Marion's birthday — which coincidentally falls on the anniversary of "the great battle [that] was fought on this ground" in the previous century — realises the following passage:

It was Doctor Jeddler's house and orchard, you should know, and these were Doctor Jeddler's daughters — came bustling out to see what was the matter, and who the deuce played music on his property, before breakfast. For he was a great philosopher, Doctor Jeddler, and not very musical.

"Music and dancing to-day!" said the Doctor, stopping short, and speaking to himself. "I thought they dreaded to-day. But it's a world of contradictions. Why, Grace, why, Marion!" he added, aloud, "is the world more mad than usual this morning?"

"Make some allowance for it, father, if it be," replied his younger daughter, Marion, going close to him, and looking into his face, "for it's somebody's birthday."

"Somebody's birth-day, Puss!" replied the Doctor. "Don't you know it's always somebody's birthday? Did you never hear how many new performers enter on this — ha! ha! ha! — it's impossible to speak gravely of it — on this preposterous and ridiculous business called Life, every minute?"

"No, father!"

"No, not you, of course; you're a woman — almost," said the Doctor. "By-the-by," and he looked into the pretty face, still close to his, "I suppose it's yourbirthday."

"No! Do you really, father?" cried his pet daughter, pursing up her red lips to be kissed.

"There! Take my love with it," said the Doctor, imprinting his upon them; "and many happy returns of the — the idea! — of the day. The notion of wishing happy returns in such a farce as this," said the Doctor to himself, "is good! Ha! ha! ha! ["Part the First," 1912 Pears Edition, 22-24]

The British Household Edition of The Christmas Books, which provides realistic images with modelled figures in the manner of the Sixties school illustrators, fails to match the visual interest of the original 1846 small-scale illustrations. Compare, for example, Dr. Jeddler's interviewing his daughters in the garden in the original series with Barnard's and Green's versions of the same scene. Richard Doyle's Part the First shows the cheerful country doctor, dressed in the appropriate, black-broad-cloth fashion of a professional man of the late eighteenth century (including a white wig), conversing with his dark-haired and blonde-haired daughters, Grace and Marion respectively, in the orchard (as indicated not merely by the trees, but by the basket of apples, centre). The pleasant scene is sharply contrasted by the aftermath of the Civil War conflict above, which, like Clarkson Stanfield's War (see below) gives only a very general notion of the chronological setting of the battle "a century earlier," and of the present. Although Barnard's second illustration for The Battle of Life: A Love Story accurately realizes the moment and even involves the philosophical country doctor's chucking Marion's chin, the original composition has the playfulness and humour typical of the earlier period of Victorian illustration — and it is precisely these endearing qualities that Barnard's far more realistic and academic treatment lacks.The photographic realism and finish of the parallel illustration in Green's narrative-pictorial sequence captures a tension between the sisters (if we may judge by the expression on Grace's face to which Marion is oblivious) that the other illustrators have missed, but fails to communicate any sense of the father as a Dickensian "character."

Left: Stanfield's description of the aftermath of the slaughter, War. Right: Stanfield's description of the same battlefield, a century later and now under cultivation, Peace (1846).

Left: Barnard's 1878 engraving of the scene in which Dr. Jeddler wishes his younger daughter, Marion, happy birthday, "Bye-the-bye," and he looked into the pretty face, still close to his, "I suppose it's your birthday" (1878). Right: Furniss's pen-and-ink study of the sisters' wishing Alfred goodbye, Alfred's Farewell (1910).

Dickens, Charles. The Battle of Life: A Love Story. Illustrated by John Leech, Richard Doyle, Daniel Maclise, and Clarkson Stanfield. London: Bradbury and Evans, 1846.

_____. The Battle of Life: A Love Story. Illustrated by John Leech, Richard Doyle, Daniel Maclise, and Clarkson Stanfield. (1846). Rpt. in Charles Dickens's Christmas Books, ed. Michael Slater. Hardmondsworth: Penguin, 1971, rpt. 1978.

_____. The Battle of Life. Illustrated by Charles Green, R. I. London: A & F Pears, 1912.

_____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

_____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1878.

_____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by A. A. Dixon. London & Glasgow: Collins' Clear-Type Press, 1906.

_____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book Co., 1910.

_____. Christmas Stories. Illustrated by E. A. Abbey. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876.

Created 1 May 2015

Last modified 17 March 2020