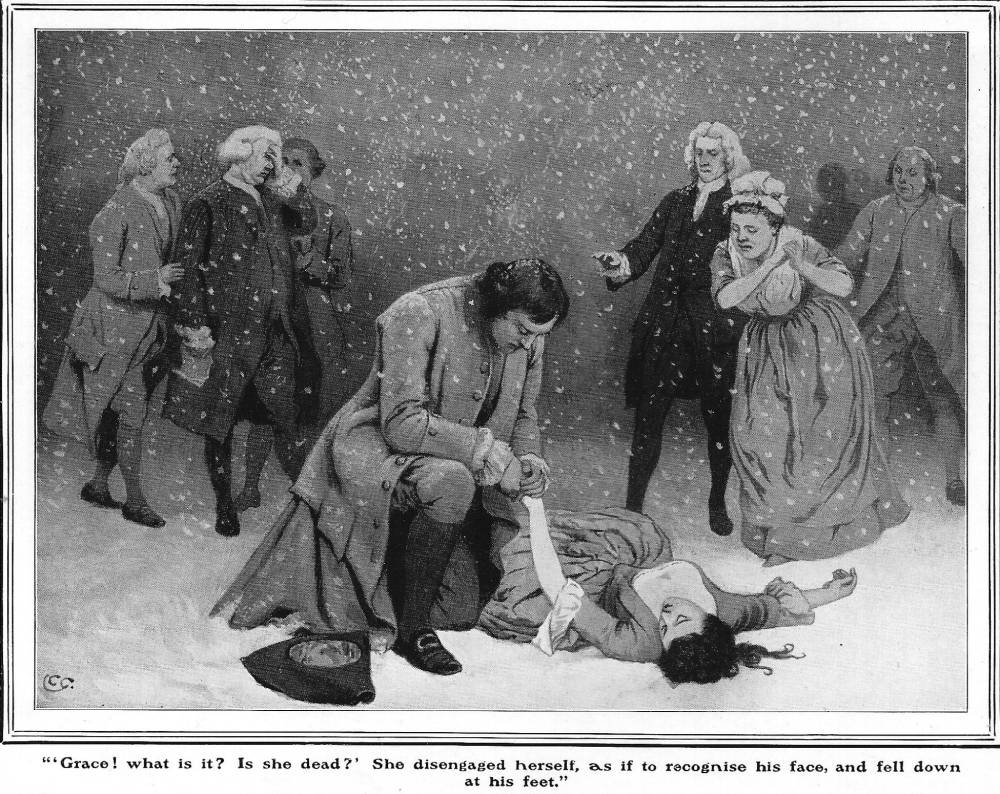

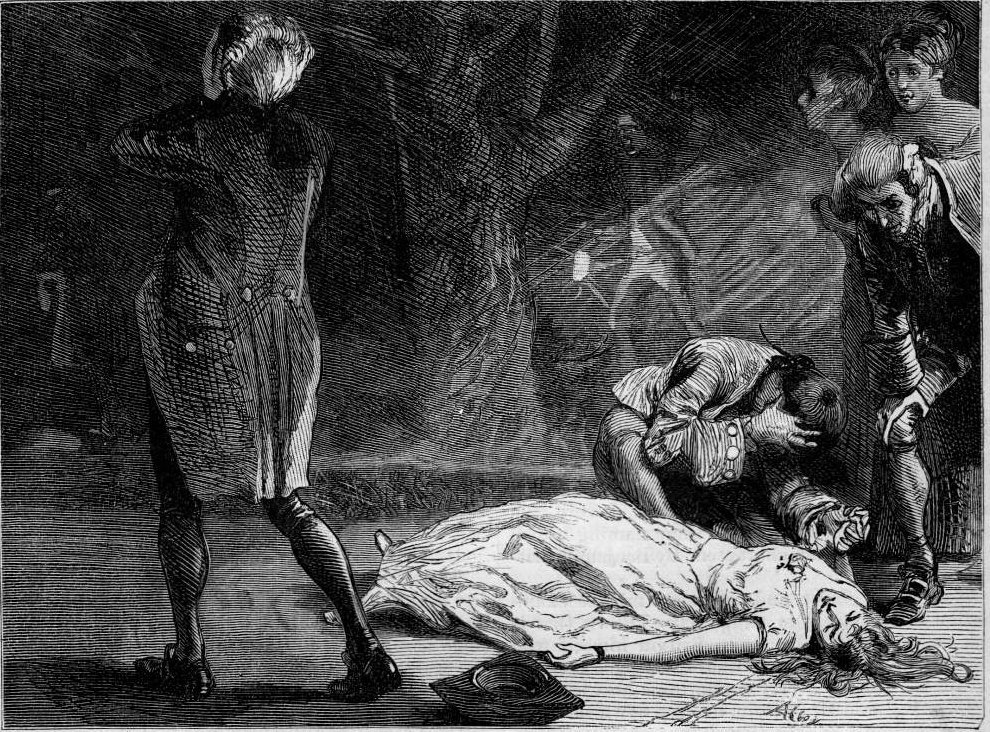

Alfred Learns the Tidings of Marion's Sudden Flight by Charles Green (56). 1893. 11.1 x 15.1 cm, exclusive of frame. Dickens's The Battle of Life, Pears Centenary Edition (1912), in which the plates often have captions that are different from the titles in the "List of Illustrations" (13-14). Specifically, the caption beneath this illustration is "'Grace! what is it? Is she dead?' She disengaged herself, as if to recognise his face, and fell down at his feet" (page 101), the second to last full page of "Part the Second."

Context of the Illustration

"What is the matter?' he [Alfred] exclaimed.

"I don't know. I — I am afraid to think. Go back. Hark!"

There was a sudden tumult in the house. She put her hands upon her ears. A wild scream, such as no hands could shut out, was heard; and Grace — distraction in her looks and manner — rushed out at the door.

"Grace!" He caught her in his arms. "What is it! Is she dead!"

She disengaged herself, as if to recognise his face, and fell down at his feet.

A crowd of figures came about them from the house. Among them was her father, with a paper in his hand.

"What is it!" cried Alfred, grasping his hair with his hands, and looking in an agony from face to face, as he bent upon his knee beside the insensible girl. "Will no one look at me? Will no one speak to me? Does no one know me? Is there no voice among you all, to tell me what it is!" ["Part the Second," 1912 edition, 102]

Commentary

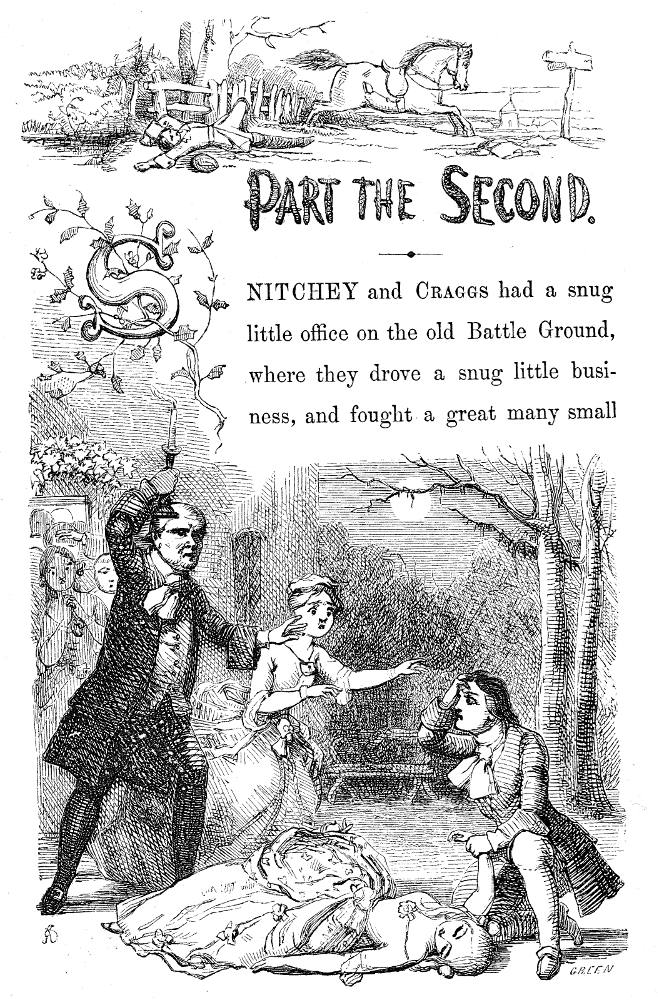

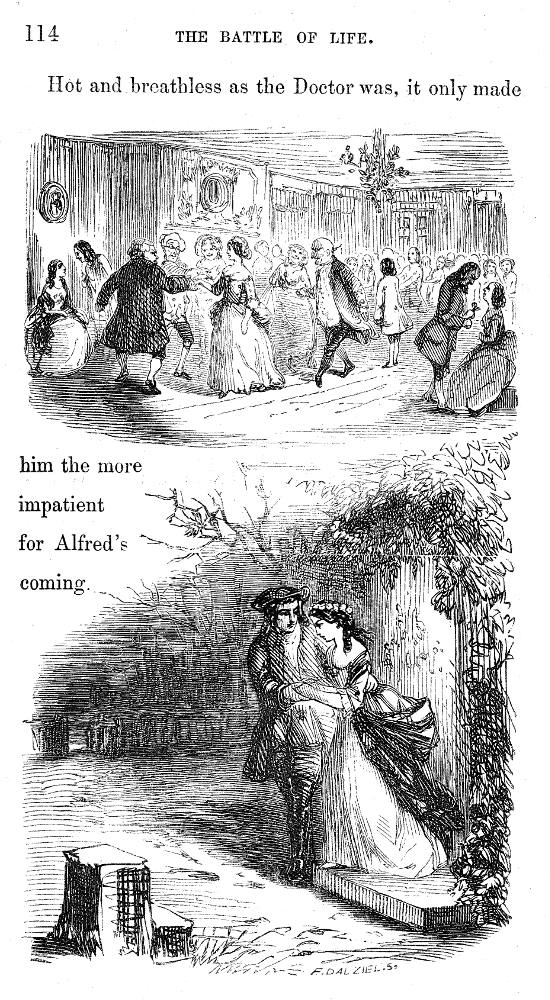

Charles Green took a rather different approach from that of Richard Doyle in the original 1846 edition of the novella. Doyle’s illustration (see below), which appears at the head of the chapter, shows the reader how Marion's secret, nocturnal departure affects her father, her sister Grace, Clemency, and the distraught Alfred. As Joelle Herr points out, "On the very day that Alfred returns to the village, a letter from Marion is discovered, detailing how she has eloped with Michael and left the country with him" (127-28). In the 1912 Pears edition, Green sets up no such expectation; in fact his initial illustration for "Part the Second" does not concern the Jeddlers at all, and instead depicts Michael Warden's troubling interview with his attorneys on page 56, well into the second chapter. Only in the fifth illustration, Dr. Jeddler reads Alfred's Letter (72), does Green introduce Dr. Jeddler in his dressing-gown perusing a letter (the caption does not indicate the identity of the writer, but in fact the letter is from Alfred, writing from abroad about his imminent arrival). Marion does not appear to be leaving with Warden until page 86 in Michael Warden's Nocturnal Interview with Marion. In fact, Green never actually introduces Marion's spurious letter, the contents of which Dickens reveals at the very close of the chapter (102). In other words,Green does not attempt to add to the misdirection of the reader by showing Marion running away with Warden, which in fact is depicted in the first edition by John Leech in The Night of the Return (see below). The reader's anticipation as he or she interacts with the text and illustrations, then, is very different, then in the 1912 Pears edition to what it would have been in the 1846 Bradbury and Evans edition.

In the first edition, the illustrator and author conspire, at the very beginning of the second movement of the story, to establish an anticipatory set in the reader's mind; the source of that suspense is not whether Marion will inexplicably vanish from the little village (for Doyle's opening illustration makes that much clear), but what events in the second chapter will precipitate her flight. Doyle in the first edition does not make clear which female character has fainted and which is running to assist the young man on his knees (logically, Alfred, but, if one may judge just from the beginning of "Part the Second" possibly Warden). However, in Alfred Learns the Tidings of Marion's Sudden Flight (101) Green clarifies the identities of the eight characters, both by their clothing and faces and by their juxtapositions: Snitchey and Craggs (distinguished, as in previous scenes, by their suits and wigs) are to the left; the portly, black-suited Dr. Jeddler, Clemency, and Britain to the right; and, in the most conspicuous, central position in this scene of almost operatic emotional excess Alfred (kneeling) and Grace (the brunette sister), who has fainted. No forest or cottage appears in the backdrop as the swirling snow obscures the scene.

In the Household Edition of 1878 Fred Barnard, having a very limited program of illustration with which to work (and knowing that the original Leech scene was very much a red herring), does not include the scene in which those at Dr. Jeddler's party emerge from the house, looking for Marion. However, in the American Edition, issued two years earlier, E. A. Abbey provides a highly convincing re-interpretation of the nocturnal scene involving the country attorneys, Dr. and Grace Jeddler, and (most significantly) in the foreground, centre, Alfred, ministering to the comatose Grace, in And sunk down in his former attitude, clasping one of Grace's cold hands in his own (see below).

Probably finding the melodramatic scene in the snow too powerfully emotionally to resist, Green realizes the discovery scene with Alfred bending over the delirious Grace. Green had probably studied the illustrations of both the original 1846 edition and the Household Edition of 1878; he offers an interpretation of the theatrical scene that incorporates some elements of the earlier visualisations. The nocturnal scene, obscured by snow, the frantic searchers, the distraught father, and Grace lying on the ground are common to all three principal previous interpretations (1846, 1876, and 1878), but Green provides clarity by the juxtaposition and placement of these figures in order to emphasize the specific reactions of Marion's fiancé and her sister.

Both the theatricality Green's lithograph illustration, which sits outside the text, and its medium distinguish it from the work of other illustrators. One must pause at the bottom of page 100, "There was a sudden tumult in the house," to read the illustration proleptically, decoding the figures, juxtapositions, and situation before proceeding to the textual equivalent of the plate. Both text and image focus on Alfred's attempting to minister to the fainting Grace. However, whereas in the text Alfred gives in to his emotions, "grasping his hair with his hands" (102), in the Green illustration, Alfred does not "look in agony from face to face," but looks steadily down at Grace, "insensible" as in the text. The reader cannot accurately assess the expression on the face of this stoic figure. Rather, the choric characters in the background convey the emotions that, in the text, Alfred experiences. Dr. Jeddler, "with his hands before his face" (102) must be the figure in front of Snitchey and Craggs (left). What the other characters are doing Dickens does not express, so that Green invents postures, poses, and juxtapositions for Clemency (wringing her hands in sympathy, right), Britain (immediately behind her, immobile), and — strangely — aniother Dr. Jeddler figure, pointing downward (right). As in a tableau vivant there is no "hurrying to and fro" but static, silent "confusion" — "disorder" without the attendant "noise." The overall effect is a stage "freeze" or tableau vivant prior to the curtain's dropping at the end of Act Two.

The overt theatricality of Green's composition reminds us that The Battle of Life, first adapted by Albert Smith for The Lyceum in December 1846, enjoyed a considerable afterlife on the stages of Great Britain and America, with eighty-three recorded productions having been staged by the end of the century.

Relevant Illustrations from the 1846and later editions

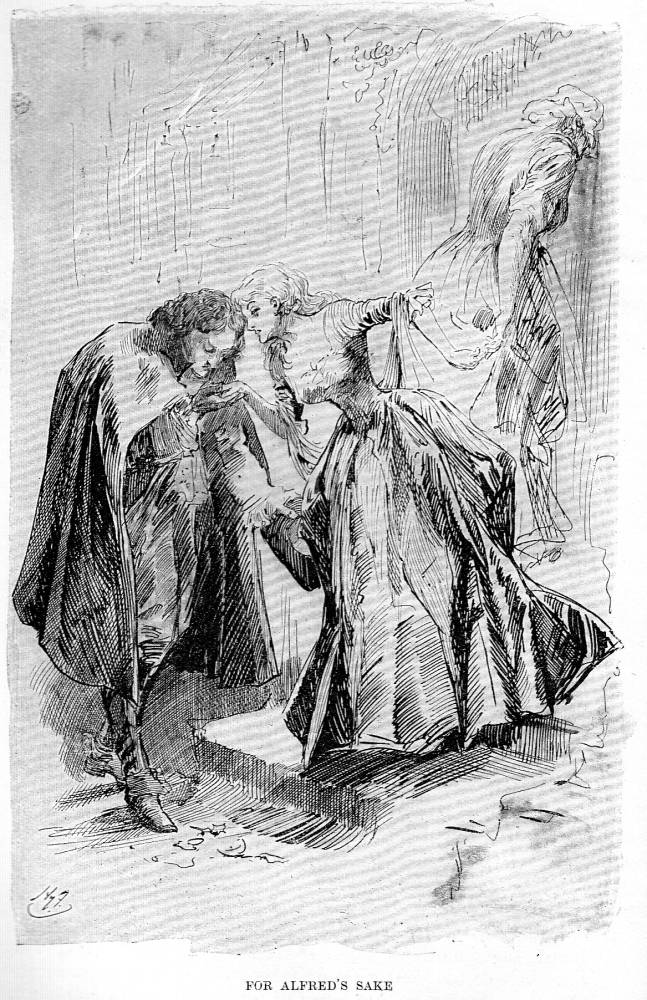

Left: Doyle's dramatic illustration of the confusion attendant upon the discovery of Marion's disappearance, Part the Second. Centre: Leech's dual illustration of the Christmas party and the supposed elopement, The Night of the Return. Right: Harry Furniss's intimation that Michael Warden and Marion are eloping, For Alfred's Sake (1910).

Above: Abbey's 1876 wood-engraving of the scene outside Dr. Jeddler's home as Alfred discovers that Marion is missing, And sunk down in his former attitude, clasping one of Grace's cold hands in his own.

Above: Barnard's wood-engraving of the scene in which Alfred, just arrived, learns that Marion has vanished into the night: "What is the matter?" he exclaimed. "I don't know. I — I am afraid to think. Go back. Hark!" (1878),

Illustrations for the Other Volumes of the Pears' Centenary Christmas Books of Charles Dickens (1912)

Each contains about thirty illustrations from original drawings by Charles Green, R. I. — Clement Shorter [1912]

- A Christmas Carol (28 plates) Vol. I (1892)

- The Chimes (31 plates) Vol. II (1894)

- L. Rossi's The Cricket on the Hearth (22 plates) Vol. III (1912)

- The Haunted Man (31 plates) Vol. V (1895)

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Bolton, H. Philip. "The Battle of Life." Dickens Dramatized. Boston: G. K. Hall, and London: Mansell, 1987. 296-301.

Dickens, Charles. The Battle of Life: A Love Story. Illustrated by John Leech, Richard Doyle, Daniel Maclise, and Clarkson Stanfield. London: Bradbury and Evans, 1846.

_____. The Battle of Life: A Love Story. Illustrated by John Leech, Richard Doyle, Daniel Maclise, and Clarkson Stanfield. (1846). Rpt. in Charles Dickens's Christmas Books, ed. Michael Slater. Hardmondsworth: Penguin, 1971, rpt. 1978.

_____. The Battle of Life. Illustrated by Charles Green, R. I. London: A & F Pears, 1912.

_____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

_____. Christmas Books, illustrated by Fred Barnard. Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1878.

_____. Christmas Books, illustrated by A. A. Dixon. London & Glasgow: Collins' Clear-Type Press, 1906.

_____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book, 1910.

_____. Christmas Stories. Illustrated by E. A. Abbey. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876.

Herr, Joelle. "The Five Christmas Novellas: The Battle of Life (1846)." Charles Dickens: The Complete Novels in One Sitting. Philadelphia and London: Running Press, 2012. 123-29.

Created 25 May 2015

Last modified 7 April 2020