Houghton’s reliance on a single (and troublesome) eye was not so much an impediment as a stimulus, encouraging his natural facility for drawing. According to Reid he worked ‘at top speed’, never did preliminary studies, and drew ‘straight on to the wood’ (p.187) in a period when it was customary to use the process of photographic transfer. The Dalziels confirm this view, noting how ‘he did not require the subject set before him’ (p.222), but composed entirely, and with great rapidity, from his imagination. The end result is a visual style which is both fanciful and extremely fluent: spontaneous and dynamic, his illustrative styles are frequently experimental, extending the limits of the idiom known as ‘The Sixties’.

Left to right: (a) King Beder in Love. (b) Gulnare [Giauharè] summoning her relatives. (c) Agib Ascending the Loadstone Rock [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

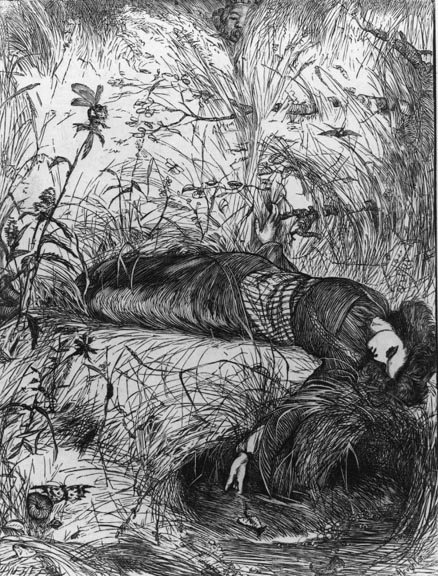

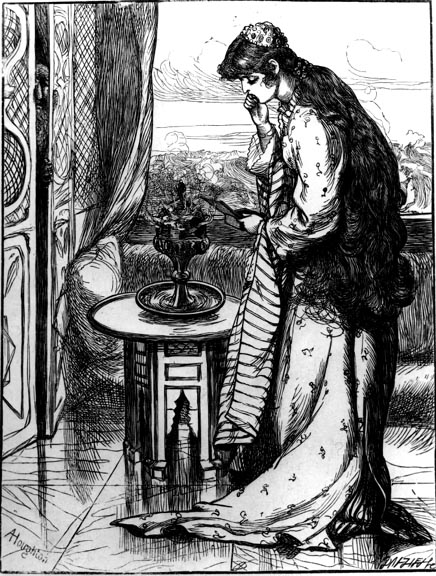

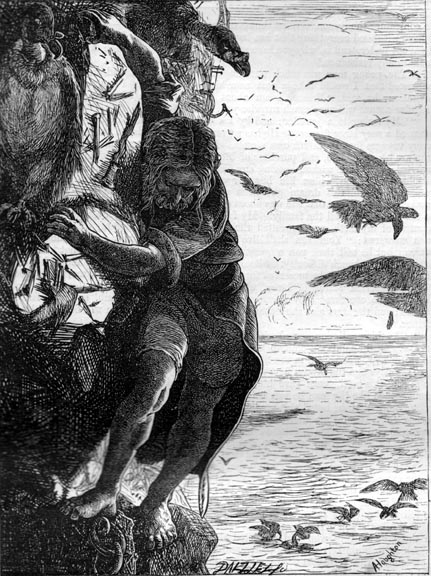

Houghton’s rapid execution is typified by his illustrations for Dalziels’ Illustrated Arabian Nights’ Entertainments (1865), which are often sketchily drawn with the surfaces worked in decorative, flowing lines. Beder in Love typifies this approach, in which the besotted character is surrounded by swirling grasses and flowers, Princess Gulnarè in Captivity is similarly treated, although it also asserts the quality of Houghton’s formal design. Lacking in detail, it epitomises the artist’s capacity to unify his compositions by accentuating recurring shapes and motifs. In this case the emphasis is on the geometrical figure of an arc shape. This device appears in the form of what appears to be a mandolin positioned in the foreground, is repeated in the curves of the Princess’s billowing dress, and is rhymed in the outlined sails of the dhows appearing in the background. Apparently spontaneous, the design’s sweeping arabesques are part of an overall scheme in which the primary stress is on pattern-making rather than description.

This tendency prefigures British art-nouveau (Russell-Taylor, p.46), notably anticipating the work of Laurence Housman, who published an important selection of Houghton’s work, along with an insightful introduction, in 1896. Houghton’s connection with the nineties foregrounds his originality as a progressive contributor to the art of the Sixties; yet his more lyrical designs were essentially eclectic, and drew on a series of mid-Victorian sources.

Princess Gulanarè

Housman describes him as ‘a direct descendant and disciple [of the] Pre-Raphaelite fathers’ (p.16), and Pre-Raphaelite imagery pervades Houghton’s romantic designs. The figure of Princess Gulnarè, with her pronounced jawline and swirling hair, is unmistakeably in the manner of Rossetti’s portraits. The treatment of her dress further recalls Millais’s fascination with the elaborate patterns found in his female characters’ crinolines, a focus especially pronounced in his images of Lucy Robarts for Anthony Trollope’s Framley Parsonage (1860–61). But equally important was the influence of neo-classical painting of the 1860s. The oriental imagery of the Arabian Nights bears a familial relationship with the exotic classicism of Frederick Leighton and Albert Moore, and there is a clear connection between the floral details in Houghton’s The Meeting of Camaralzaman and Badoura and the Aesthetic devices found in paintings such as Moore’s Azaleas (1868, Hugh Lane Municipal Gallery of Art, Dublin). The contemporary taste for Japanese prints and ceramics also features in his designs, and provides a further link with the paintings of Rossetti and Whistler.

Houghton’s fusion of influences, in part neo-classical, in part Pre-Raphaelite, and in part Japanese, is one of the central characteristics of his ‘oriental style’. The effect is ornamental and self-consciously pleasing: decorative patterns designed to beguile the eye. Houghton’s charm is matched, however, by a variety of other styles, which challenge the refinement of his calculatedly beautiful characters and lyrical arabesques.

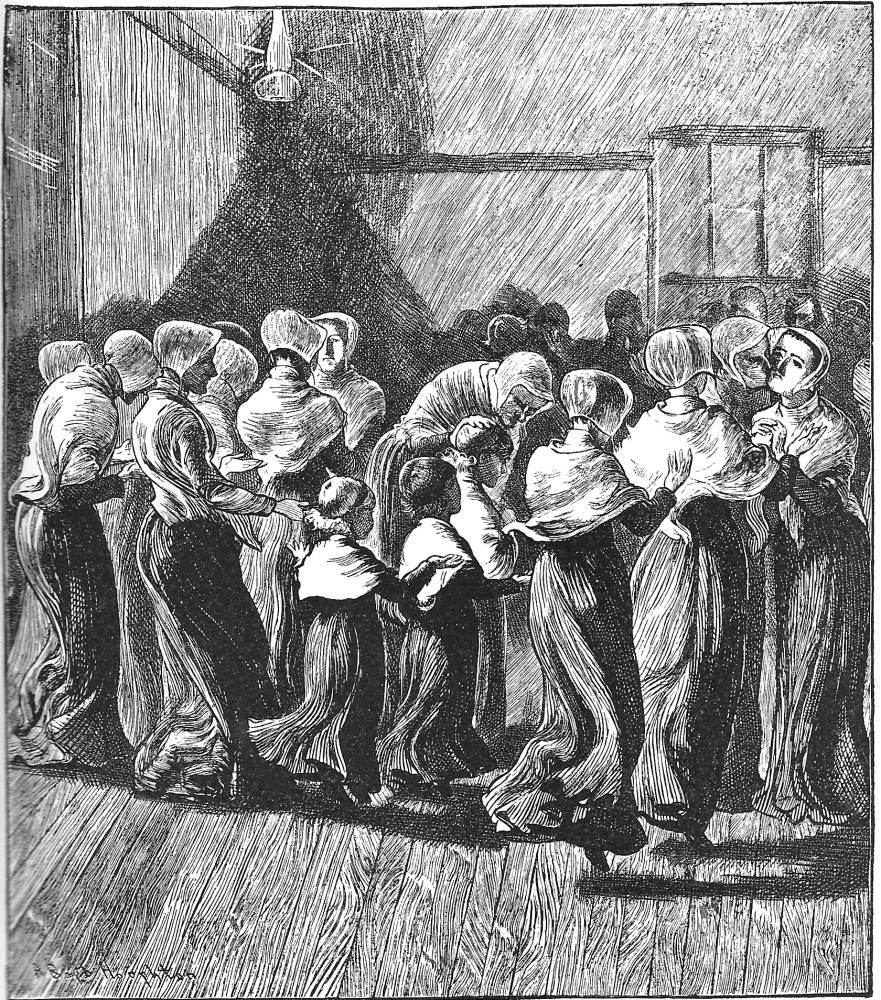

Though a practitioner of poetic lyricism, Houghton was also adept in the practice of the grotesque. His ‘oriental style’ is characterized by lightness, ornamental detail and beautiful faces, but he was equally adept in the manipulation of mask-like distortions and ugly situations. These elements are typically combined with an expressionistic chiaroscuro. In his images of ‘Meg Blane’ for Robert Buchanan’s North Coast (1868) we have a typical example of Houghton’s dark manner. The figures fearfully huddle around the drowned body; the victim’s limbs and face are picked out in dim illumination; and the whole group is placed asymmetrically within the frame. Houghton is at his most powerful, however, in his representation of what can only be described as strange and threatening domestic scenes. The home idyll is typically represented by artists such as Robert Barnes and Frederick Walker, but Houghton explores the inner tensions of family life. This approach is embodied throughout his illustrations for ‘Meg Blane’, and is a key characteristic of his designs for Home Thoughts and Home Scenes (1865).

Houghton’s capacity to represent fear and alienation is further deployed in his illustrations of the working-classes. Though journalistic, his images of the poor focus on a sort of psychological disconnectedness in which the characters do not gaze at each other, but seem absorbed in the strange randomness of the urban experience. This approach features in his images of the London streets for The Graphic, and again in his celebrated Graphic America series. Adept at showing the fantastical in the form of his oriental pictures and in his illustrations for Don Quixote, Houghton also provides a sharp satirical commentary on the conditions of modern living. As the Dalziels explain, Houghton had a ‘fine sense of humour … coupled with a pleasant tinge of satire’, the attitude of a man who ‘knows the world in its various phases’ (p.222).

Left to right: (a) The Voyage. (b) Hiawatha and Minnehaha. (c) Shakers dancing [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

Related Material

Last modified 19 August 2013