fter illustrating the work by Charles Reade that was to become The Cloister and the Hearth,, Keene’s next project was George Meredith’s Evan Harrington; or, He Would be a Gentleman. This serial was a huge undertaking of forty illustrations, appearing in Once a Week from 11 February to 13 October 1860; like A Good Fight, it was part of the process of winning readers, although unlike Reade’s turgid fiction Meredith’s was widely appreciated.

Lucas’s use of Keene was motivated by complex considerations and one of these must have been the pairing of text and illustrator. This had practical and artistic dimensions. Lucas’s insistence that illustrators should not consult with their authors must have been difficult for Reade, who firmly believed the artist should come under the writer’s control. This was the model he adopted in his dealings with Robert Barnes, his collaborator on Put Yourself in His Place (The Cornhill Magazine, 1869–70), and his incapacity to manipulate Keene may explain his resentful condemnation of the artist’s designs for A Good Fight as ‘below the level of the penny press’ (qtd.Pantazzi, p.44). All Lucas wanted was a seamless fit between the artist and the text, and in matching Keene and Meredith he found a more harmonious arrangement. Though interested in illustration, Meredith was willing to accept Lucas’s dictum and allow the artist to make of Evan Harrington whatever he wished. There was ‘no consultation’ between the partners creating the dual text, and Meredith trusted Keene to select his ‘own incidents’ (Layard, p.64) and work to his ‘own devices’ (Pantazzi, p.44).

Meredith’s, and Lucas’s, confidence was well-founded. A Good Fight had been a risk, but the editor’s selection of Keene as Meredith’s illustrator was based on the firmer ground of a basic equivalence between the writer and artist’s interests. Keene’s experience as a social commentator working for Punch equipped him to illustrate Meredith’s analysis of sexual and class politics, and there was a basic correspondence between Keene’s interest in class and the behaviour of the lower ranks and Meredith’s exploration of social mobility in his tale of a tailor’s son who ‘would be a gentleman’. This accordance was noted by J.A. Hammerton in his 1911 study of Meredith’s life and writing, noting the aptness of Lucas’s selection as

A happy chance when the editor of Once a Week gave the story to Charles Keene to illustrate. Of all the author’s novels this is the only one in which Keene could possibly have felt at home. It moves at times along the same paths of characters which the artist was wont himself to pursue. [p.376]

Working in this shared spirit, Keene focuses on the relationships between the characters. Meredith is primarily concerned with notions of embarrassment and the small nuances of etiquette, and Keene gives these interests a distinct visual form which extends beyond the writing and gives it an intense immediacy. He amplifies and deepens Meredith’s drama by focusing on significant looking, facial expressions and physical interactions, usually as a matter of a face to face confrontation. This involves both responsiveness to the writing and the addition of his own, highly inflected readings.

His emphasis on gesture, gaze and expression is exemplified by the illustration showing the embarrassing interview between Evan and the Countess. The author provides many prompts to suggest how the two characters should look: Evan is ‘wretched’, forbidden to sit down; the Countess has a look of ‘speculative amazement’ as she rocks in her chair; and Evan stands ‘silent, flinching’, as her ‘frank eyes’ scrutinise his face, compelling him to confess to his guilt (Once a Week, 3, p.199). All of these telling signs are embodied visually in Keene’s design, but the artist takes the situation into another domain of suffering. Meredith presents her ladyship as domineering – a woman who presents ‘things spoken as facts’ – but Keene posits the idea that Evan is quite literally as if he were on trial. Meredith tells us that she is like a lawyer, with a ‘judicial mind’ and Keene shows her, in details of his own, as if she were a judge deliberating on his sentence. She holds a finger pensively to her mouth, while Evan is a defendant, standing rigidly as if in an imagined dock; his hand is placed in an assertion of honesty on his chest and his face is distorted into a mask of pained anxiety.

Left to right: (a) Miss Shorne and Rose. (b) Watteau-like groups. [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

Keene’s illustration works, in other words, to stress Evan’s lowly status in the world of privilege; simply by being involved in a romance with someone in a higher class than himself he automatically places him in a defensive position, as if he were a criminal under the prosecutor’s cross-examination. The blunt directness of the illustration adds another, unsettling dimension to Meredith’s analysis of class difference, converting it into a matter of class conflict in which power is always vested in Evan’s superior. But Keene takes the analysis even further, revealing the underlying truth of the situation. He depicts the Countess as physically dominant, with her huge crinoline and chair occupying the main part of the composition; she may have the authority of the law, but her monumental presence suggests she is a bully who denies her victim any space. Most telling of all is the way in which he places Evan at the left of the design with her ladyship’s dress pressed against him, as if she were literally pushing him out of the frame. This is an ingenious visual metaphor which highlights the unspoken premise of Evan’s situation: his betters want him out of the frame and the artist shows him being quite literally pushed out of view. In common parlance, he is standing on ‘uncertain ground’, ‘doesn't have a leg to stand on’, and is in danger of being ‘edited out’. This type of complex enrichment is pursued throughout the illustrations.

Left to right: (a) The close of the pic-nic. (b) In which Evan’s light begins to twinkle. (c) Her ladyship commenced rocking in her chair [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

The question of social inequality is explored in illustrations which show Evan’s dealings with his betters and in his interactions with those who are supposedly his inferiors. Keene is at his sharpest in his representation of the moment when Evan pleads for a bed with a group of old cronies in their local inn (2, p.287). This shows how the hero behaves when he has to engage with the social milieu he is trying to escape: his response is one of embarrassment, and Keene focuses on the contrast between his hesitantly raised hand and the steady gaze of the drinkers. The effect, though, is markedly different from the meeting with the Countess. Evan is embarrassed at having to ask for their indulgence, but still speaks politely and on equal terms, his topper held to the side of his head in a humble gesture. There is none of the arrogance that characterises the body language of those in the superior class, and the illustration subtly reveals the fundamental difference between the hero and his social betters. In an important essay Royal Gettman reads the fiction as a novel about ‘the testing of a tailor’s son against the temptations of snobbery’ (970), and Keene’s illustrations consistently point to the differences between manners and social attitudes, representing small variations in attitude and gaze which, though practically invisible to modern readers, must surely have been apparent to the original audience.

Keene’s training as a satirist at Punch is well-applied in this reading of the social theme. He is equally adept in manipulating small nuances of gaze and gesture as a means to represent the behaviour that supports social difference and the tensions between the classes. He focuses especially on the visual language of romance, the intimacy of women’s conversations and. the sharing of confidential information.

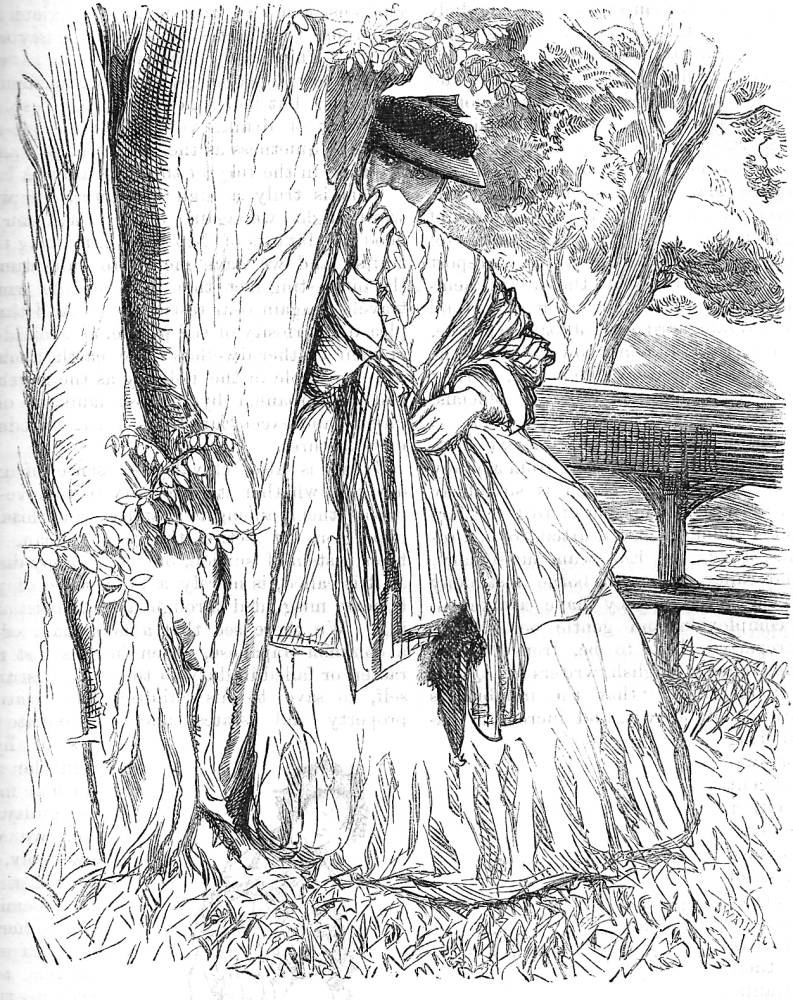

The passing of secrets and suspicions is charted in the meeting of Rose and Mrs Shorne (Once a Week, 3, p.1), where the two characters are characteristically engaged in an exchange of glances and gestures; in the meeting of Raikes and Remand (3, p.281); and again in ‘The Lover’s Parting’ (3, p.421). Each of these is a dynamic tableau, infusing Meredith’s dialogue with a strong sense of fluidity: the characters constantly move and this condition, Keene implies, is realised in the passing of information which is instantly questioned or contradicted. These images point to the formality of such exchanges, implying that social behaviour is both expressed and constrained by the rules of propriety.

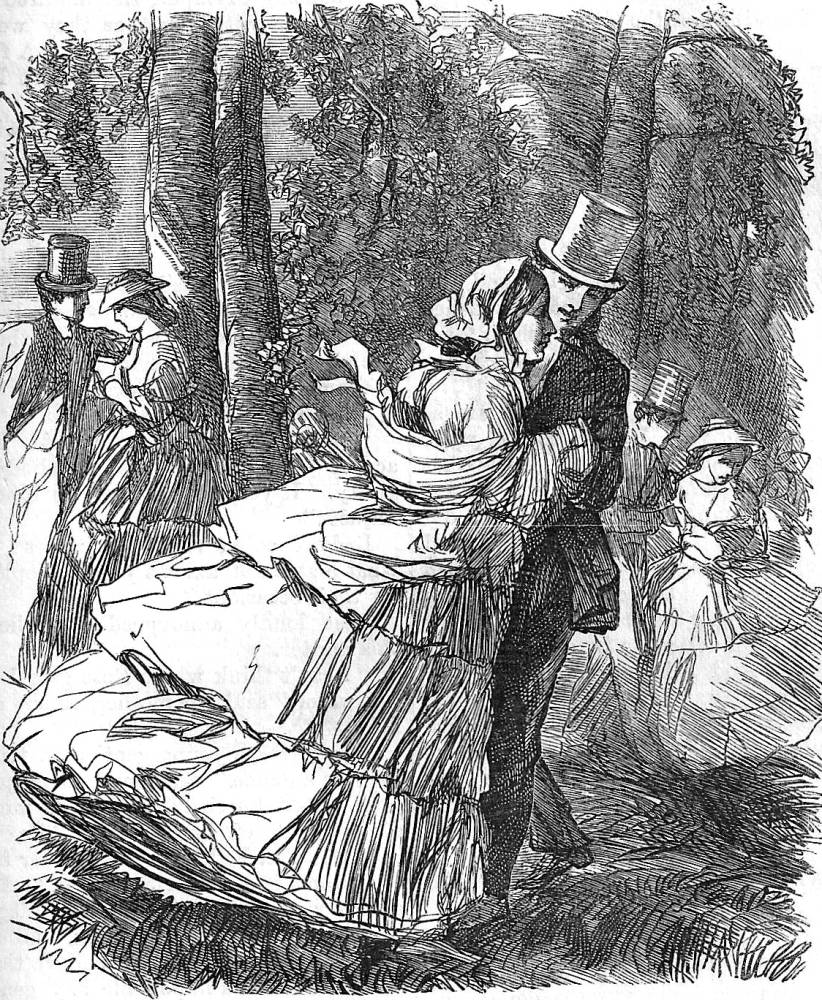

Indeed, the focus on small gestures points to the key message that Keene discovers in Meredith’s text. The author examines class and snobbery, but the artist constructs a deeper understanding of class and identity in which he reveals the differences between the ways in which individuals express their feelings – and how they express them when they forget the social role ascribed to them. One cohort of his illustrations articulates the characters’ class consciousness, but he also shows spontaneous, innocent moments when feeling rather than propriety is his theme. These are dynamic, unreflective experiences. In the image ‘in which Evan’s light begins to twinkle again’ (3, p.141) the characters swirl in a dance, and in ‘before breakfast’ (p.225) Rose and Polly have a conversation in the bedroom, with Rose’s back turned to the viewer. The effect is one of informality and spontaneity, an image of the ‘natural’ language of gesture, unimpeded by any social considerations. That Keene shows the servant in the dominant position with the mistress stretched out in an ungainly one is a powerful insistence of the value of equality, or at least mutual respect. It forms a marked contrast to Evan’s interview with the Countess, and suggests the artificiality of the world he seeks to enter.

The illustrator is at his most insightful in his charting of the tensions between these two sets of behaviours – one free and spontaneous and the other constraining. The most representative design shows the meeting between Evan and Rose in the street (2, p.253). This is a highly emotional moment; Rose’s ‘dear bosom’ is ‘heaving’ and Evan is ‘tempted to fall on his knees to her with a wild outcry of love’. However, spontaneous feeling is defeated by ‘the inexorable street’ (p.232). In the illustration Jack and Laxley are involved in a fraças in the background, but Evan and Rose are immobile, woodenly holding hands, he with a downward and she with an averted gaze. This intricate composition depicts the tensions between propriety and natural behaviour; the street imposes its own rules (middle-class people would not or could not embrace in such a setting), while the underlying desire is entirely at odds with the situation.

Keene’s designs might thus be described as an analytical accompaniment to Meredith’s text in which the artist responds to its social themes but finds other, related meanings inscribed in its writing. Meredith focuses on the absurdities of social mobility, but Keene is far more concerned with the artificiality of elite behaviours and especially how it cramps natural affection. Such subtleties have not always been noticed or appreciated, however. Criticism has been ambiguous and sometimes hostile. Hammerton, sensitive to the matching of thematic concerns, notes how the illustrations were at least ‘not an impertinence to the novelist’ (p.378), though S. M. Ellis views them as being of ‘unequal merit’ (p.131). Goldman describes them as ‘inventive’ (p.233) and for Forrest Reid the images are ‘equal to any that were ever made for a novel’ (p.123). Such high praise acknowledges their quality while reflecting on their lack of status when compared to work by Millais; Lucas’s view is unknown. However, the final judgement must be Meredith’s. As far as he was concerned, so G.S. Layard tells us, ‘the pictures gave [him] entire satisfaction’ (p.64). Sophisticated, various and suggestive of how we might read Meredith’s text, Keene’s engravings are a prime example of the clever combination of illustration and interpretation, respectful adherence to the text while enriching our responses to it.

Links to Related Material

- Meredith and His Illustrators

- Evan Harrington, The Adventures of Harry Richmond, and the Evolutionary Debate of the 1860s

Works cited and sources of information

Buckler, William E. ‘Once a Week under Samuel Lucas, 1859–65.’ PMLA 67 (1952): 924–41.

Cooke, Simon. ‘George du Maurier’s Illustrations for M.E. Braddon’s Eleanor’s Victory in Once a Week.’ Victorian Periodicals Review 35:1 (Spring 2002): 89–106.

Cooke, Simon. Illustrated Periodicals of the 1860s: Contexts and Collaborations. Pinner: PLA; London: The British Library; Newcastle, Delaware: Oak Knoll Press, 2010.

Brothers Dalziel, The. A Record of Work, 1840–1890. 1901; new ed. London: Batsford, 1978.

Gettman, Royal A. ‘Serialization and Evan Harrington.’’ PMLA 64 (1949): 963 –975.

Goldman, Paul. Victorian Illustration: the Pre-Raphaelites, the Idyllic School and the High Victorians. Aldershot: Scolar, 1996; new ed. London: Lund Humphries, 2004.

Hammerton, J.A. George Meredith: His Life and Art. London: Grant, 1911.

Houfe, Simon. The Work of Charles Samuel Keene. Aldershot: Scolar, 1995.

Layard, G. S. The Life and Letters of Charles Samuel Keene. London: Sampson Low, Marston & Co., 1892.

Marsh, S, M. George Meredith: His Life and Friends in Relation to His Work. London: Richards, 1920.

Meredith, George. ‘Evan Harrington’. Once a Week 2 –3 (11 February to 13 October 1860). Illustrated by Charles Keene.

Meredith, George. Evan Harrington. London: Bradbury & Evans, 1861. This first edition, in 3 volumes, does not include the illustrations by Charles Keene.

Meredith, George. Evan Harrington. London: Bradbury & Evans, 1866. The first single volume edition, with one illustration by Keene as the pictorial frontispiece.

Last modified 21 May 2014