ritish book design of the 1890s was dominated by the new style of Art Nouveau and was carried forward by a small number of outstanding artists. Aubrey Beardsley, Charles Ricketts and Laurence Housman were the foremost practitioners, producing books which offered a radical new imagery to Victorian elites (in the form of limited and special issues) and to the wider public (in trade editions). There were, however, a number of other, less prominent designers who nevertheless made a significant contribution to the development of end-of-the-century aesthetics. Fred Mason was one of these creators of a British version of Art Nouveau, and equally productive were Alfred Garth Jones and William Brown Macdougall.

Taken as a whole, these book-artists reanimated book-design, partly by deploying the motifs of Art Nouveau and partly by unifying their publications’ aesthetic effects by working as the designer of their publications’ exteriors and interiors. The result was the rise of a new type of book in which the pages and boards were conceived as a unified whole within a visual scheme. Any assessment of these figures must therefore involve a consideration of their work as illustrators and page-embellishers along with analysis of their bindings.

Entries in the book design sections of the Victorian Web consider these two aspects, but my focus here is one of the lesser-knowns – Macdougall. Macdougall designed the outsides and insides of his books and in so doing produced a version of Art Nouveau which was both forward-looking and a response to the traditions of Arts and Crafts. Working in the nexus between two styles, Macdougall is an interesting figure whose status as a secondary talent is perhaps undeserved. In the 1890s his work was subject to some hostile and negative criticism, but with the advantage of hindsight it is possible to establish a balanced view which accords him a greater significance that has previously been the case.

Background and Work

Macdougall (1868–1936) was a Scot. Born in Glasgow to middle-class parents, he was educated first of all at an elite public school, the Glasgow Academy (which was set up in 1845), and later, in the mid-1880s, at the Académie Julian in Paris (founded 1868). Both institutions were fee-paying and Macdougall benefitted from family support.

William Brown Macdougall, a plaster bust by Frank Mowbray Taubman. [Click on this and the following images for further information and larget images.]

While at the Académie the artist acquired the essential, traditional skills of image-making, with an emphasis on drawing, modelling and perspective. That point should be stressed because it is often claimed that the Académie was a modernizing, unconventional institution that accepted female students and played an important part in the development of training for women; so much is true, but it was otherwise a conservative provider. Its instructors – among them the French painters Paul Laurens, Tony Robert-Fleury and William Bougurereau – were essentially establishment figures associated with the Salon, and Macdougall would have been taught the ‘academic’ curriculum that prepared students for further training in the Parisian École des Beaux Arts.

However, Macdougall did not proceed in his French art-education. Instead, from the end of the 80s he became a versatile painter producing landscapes, portraits and historical and genre scenes. He exhibited these works at a variety of venues, both traditional and more progressive, notably the Scottish Royal Academy and the exhibition spaces of the New English Art Club, which he joined in 1889 or earlier (Steenson 35). His membership of the Club was emblematic of his status as a French-trained Briton; it was first proposed to call the organization ‘The Society of Anglo-French Painters,’ and Macdougall exhibited alongside many artists who straddled the Channel, among them Walter Sickert, George Clausen and Stanhope Forbes. NEAC had been set up as an avant-garde institution to challenge the dominance of the Royal Academy, yet Macdougall’s paintings are remarkably conservative and closely reflect the traditional approaches of his French masters.

Conventional image-making was only a part of his career, however. In addition to working as a jobbing painter, Macdougall practised as an etcher, wallpaper designer, wood-block artist, print-maker and illustrator, and it was in graphic art, rather than his work in paint, that he displayed a degree of adventurousness. Some of this effort was vested in his evocative, semi-abstract landscape and topographical prints, a mode he practised in the 1920s and 30s. But more impressive were the book designs in which he developed his own versions of Art Nouveau. Although his Victorian oeuvre in black and white was confined to around a dozen books of the 1890s, these are publications of considerable visual impact.

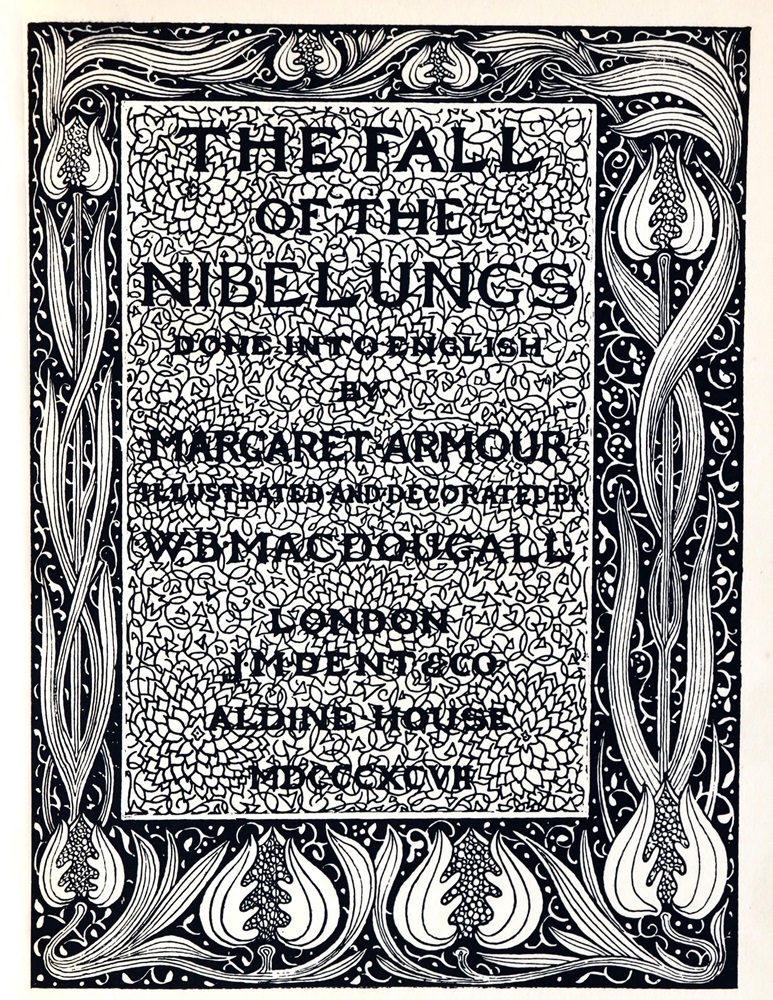

This small, intense corpus extended from contributions to the most outstanding periodicals of the time, The Yellow Book (1894) and The Savoy (1896), and also embraced classic texts and reprints such as his treatment of Dante Rossetti’s The Blessed Damozel (1898), Keats’s Isabella or, the Pot of Basil (1898) and The Book of Ruth (1896). However, the main part of Macdougall’s work was in the form of illustrations and marginal devices for the work of his wife, the poet and translator Margaret Armour. Macdougall married Armour in 1895 and thereafter created full-page designs, initial letters, borders, end and tail pieces and bindings for each of her books. This work included bold designs for collections of his wife’s original projects, notably The Shadow of Love (1898), parallel imagery for her edited anthology of supernatural tales, The Eerie Book (1898), and floral and neo-medieval borders for her translation of The Fall of the Nibelungs (1897). He also illustrated minor publications in the period after 1900 and continued with his painting well into the twentieth century. He died in 1936, an artist who, by now, was barely remembered.

Style, Influence Idiom: Searching for a Voice

Macdougall was an eclectic, transitional artist who drew on the competing styles of William Morris and the emergent idiom of Art Nouveau. In the 90s both modes were current, and Macdougall oscillates between the two, sometimes using one or the other, and sometimes synthesizing both varieties to create a hybrid. This development can be traced in his figure illustrations and in his decorative borders and ornamental devices.

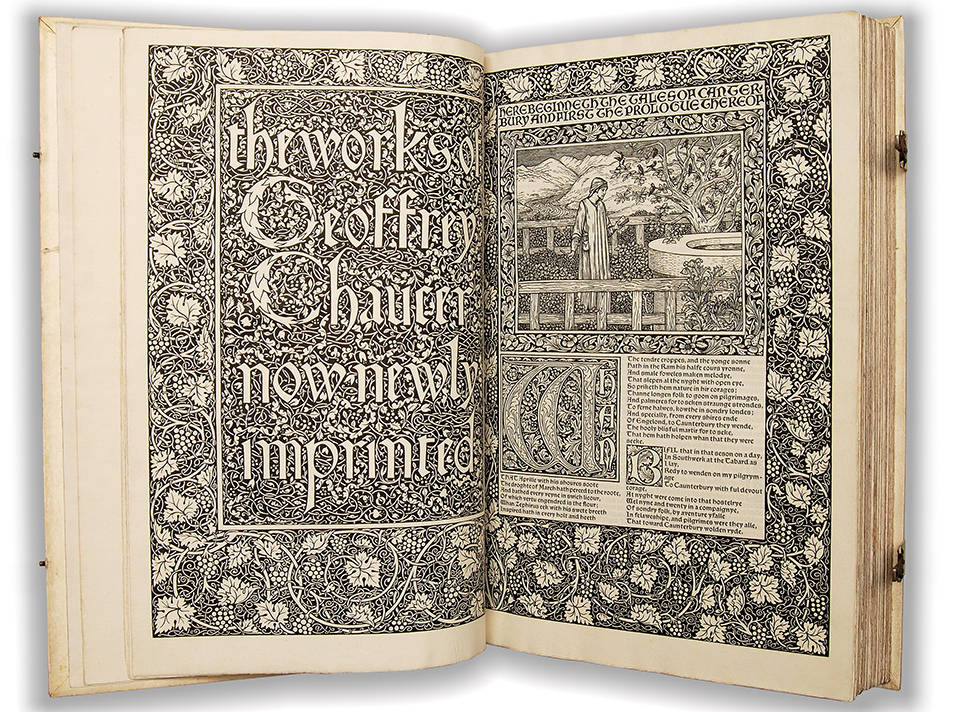

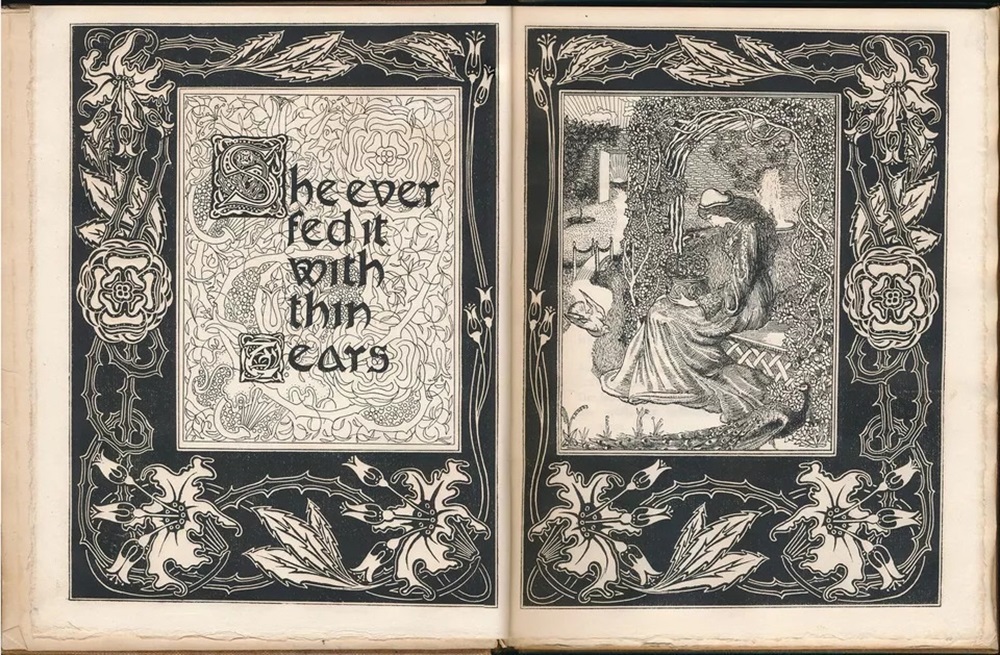

Most of Macdougall’s figures are in the manner of Art and Crafts and are closely modelled on Burne-Jones’s Pre-Raphaelite characters in his paintings and in the ‘Kelmscott Chaucer’ (1896). Macdougall adopts the older artist’s combination of archaic costumes and settings along with Burne-Jones’s Gothicising, elongated, attenuated treatment of the body. This approach is exemplified by the figures in The Fall of the Nibelungs and Isabella (1898), images which bear direct comparison with Burne-Jones’s Boethius De Consolatione Philosophie and The Franklin’s Tale. The relationship is stressed by the fact that both sets of images are engraved on wood – inscribing the evocation of the (imagined) past in the imagery and in the graphic technique.

Macdougall’s work in the manner of Arts and Crafts, which bears direct comparison with the art of Burne-Jones. Left: a scene from The ‘Kelmscott Chaucer’ (1896) by Burne-Jones; and Right, an illustration from Macdougall’s The Fall of the Nibelungs (1897).

It seems likely that Macdougall had direct access to Morris’s monumental tome.

The influence of Morrisonian Arts and Crafts is continued in Macdougall’s congested borders and decorative fields, and it is interesting, again, to compare the following:

Left: the title page of the ‘Kelmscott Chaucer, by William Morris. Right: Macdougall’s dense work for the opening of The Fall of the Nibelungs.

On the other hand, Macdougall sometimes shifts idiom to present figures and full-face portraits which move away from medievalist Arts and Crafts and are drawn in the manner of an ethereal Art Nouveau. His characterization of Kriemhild and the Falcon in The Fall of the Nibelungs (1897) typifies this approach, and the same can be said of A Woman’s Head in The Savoy (1896). In each of these the emphasis is on the sinuousness of the delicate line, the flatness of the image, the contrast between the negative and positive space and the deliberate mismatch of details so that Kriemhild’s hand is far too small in relation to the head, while the falcon is diminished to an ornamental, pet-like status. What Macdougall does, in other words, is deploy the sorts of distortions and simplifications that are central to Art Nouveau; as John Russell Taylor observes of the style, he uses a ‘mannered … affectation’ to create a ‘sophisticated’ and ‘decorative’ effect that moves away from the ‘gothic hankerings’ and ‘revivalist fervour’ (56) of Arts and Crafts as it is registered in William Morris’s imprints.

Macdougall in his Art Nouveau mode. Left: Kriemhild and Falcon, and Right: Woman’s Head.

What, then, was the impetus behind Macdougall’s version of the ‘New Style’? The prime influence, unsurprisingly, was the foremost proponent and pioneer of British Art Nouveau, Aubrey Beardsley. Macdougall seems to have known Beardsley as a friend, and contributed to both of his periodicals, The Savoy and The Yellow Book, for which Macdougall contributed an Art Nouveau image, The Idyll (1894). No doubt this connection led to professional conversations and there it is absolutely the case that Beardsley’s work provided an exemplar for Macdougall’s.

Beardsley provided models of figure drawing in his Morte D’Arthur (1894) that are clearly emulated in Macdougall’s Eerie Tales (1898). Further, the characters in this collection of supernatural stories are depicted in sinuous lines which imitate Beardsley’s drawings in The Yellow Book, and Macdougall emphasises ‘the bold use of black and white and space to produce [the] unsettling and eerie effects’ (Cuneo & Hacker) which feature throughout his mentor’s art.

Beardsley’s impact is most registered, however, in Macdougall’s decorative borders and ornamental devices. The Scottish artist endowed most of his books with powerful marginal designs: some, such as those in The Fall of the Nibelungs (1897), have the congested intricacy of Morrisonian Arts and Crafts, resembling the borders in the ‘Kelmscott Chaucer’ and Morris’s wallpaper designs; but the majority of his border-work is dazzlingly extravagant, featuring distorted floral motifs and tendrils which are derived from and develop Beardsley’s borders in Morte D’Arthur.

Two examples of Macdougall’s borders: Left: The title page for The Book of Ruth, and Right: a border for Isabella, or The Pot of Basil.

Indeed, in most of his work Macdougall is unmistakeably Art Nouveau in manner, combining Beardsley-like abstractions with stark contrasts of black and white, muscular, writhing, sinuous lines, and organic, repeating patterns; equally important is the designs’ flatness, which as a visual field for the articulation of ‘classic’ Nouveau motifs, notably the thorn, the heart and the vine. Dante Rossetti’s The Blessed Damozel and Armour’s Songs of Love and Death (1898) include all of these features and are extraordinarily complex and imposing. Though inspired by Beardsley’s designs, Macdougall creates a series of intense patterns which are far more accomplished than his figure drawing and show that his real strength lay in decorative and ornamental effects, endowing his books with great presence and impact. As one critic observed of The Fall of the Nibelungs, his illustrations are ‘not powerful’ but his ‘marginal decorations … are often excellent’ (‘The Fall’ 107–108); energizing the page, they seem to writhe of their own accord.

Two examples of Macdougall’s lettering Left: The title for Isabella, in the style of Art Nouveau and Arts and Crafts; and Right: the same combination in some lettering for The Fall of the Nibelungs.

Reception and Significance

Macdougall’s development of the art of the border rescues him, so to speak, from the accusation of imitation or excessive derivativeness: he responds to Beardsley’s decorative devices, but takes them to a higher level of avant-garde novelty and visual impact. In his hands, Art Nouveau is an ever bolder and more challenging style. We might expect that approach to be appreciated at the time of publication, but it is interesting to note that Macdougall was not generally regarded as an accomplished graphic artist.

Two examples of Macdougall’s work in pure Art Nouveau. Left: an illustration and decorative border from Armour’s Songs of Love and Death; and Right: a bold border for D. G. Rossetti’s The Blessed Damozel.

He did earn some positive reviews, but for the most part his work was disparaged, with many critics regarding his version of Art Nouveau as strange, ugly and discordant, rather than daring and ‘modern.’ One critic accuses him of ‘imbecility’ (‘Fine Arts – The Fall of the Nibelungs’ 531) and others are almost as extreme. Of The Book of Ruth, for instance, an observer remarks that its decoration is ‘queer’ and ‘curiously destitute of solidity and grace’ (‘Fine Arts–The Book of Ruth’ 801), while for another, speaking of the borders for The Blessed Damozel, the effect is ‘black and heavy … a very grave fault’ (‘The Blessed Damozel,’ The Studio 289). Indeed, the borders’ alleged heaviness seems to have been a significant issue, with several critics describing them as ‘heavy’ and inappropriate’ (‘The Chronicle of Art’ 174); looking for faults, one commentator bizarrely complained that the ink was so heavy as to leave ‘a somewhat unpleasant scent’ (‘The Blessed Damozel,’ Art Journal 288).

Martin Steenson speculates on the reasons for the ‘sudden halt’ to Macdougall’s work in 1898, wondering if he had ‘run out of ideas’ (39) following his rapid issue of books in the period 1897–98. Perhaps he had, having saturated the market with his particular brand of illustrated gift book. But the reason for issuing no more must surely be that the artist could not continue under the weight of such unsympathetic criticism. In more practical terms, it might simply be that the negative press was a death blow to sales, and that publishers were no longer interested in what might have been perceived as a risk, especially given the fact that most of his books are luxurious editions and would have been expensive to print and bind. That point is borne out by the fact that Macdougall did not stick with a single publisher, issuing three of this titles under the auspices of Dent, two with Duckworth, one with Macmillan and another with Kegan Paul; the others were published by the lower-status names of Shiells and White, and that movement suggests that he was forced to move around in pursuit of publishers willing to take a risk.

Condemned as ‘queer,’ Macdougall’s books were perhaps too radical in their final formulation of British Art Nouveau. Despite his eclecticism, the artist might thus be understood as an unconventional proponent of the new style, and one who takes a significant place next to his mentor Beardsley. The power of his designs is appreciated by modern collectors, and Macdougall’s small body of work commands high prices in the antiquarian book-trade.

Bibliography

Primary

Armour, Margaret (ed). The Eerie Book. London: Shiells, 1898.

Armour, Margaret (trans). The Fall of the Nibelungs. London: Dent, 1897.

Armour, Margaret. The Shadow of Love. London: Duckworth, 1898.

Armour, Margaret. Songs of Love and Death. London: Dent, 1896.

The Book of Ruth. With an introduction by Ernest Rhys. London: Dent, 1896.

Keats, John. Isabella, or The Pot of Basil. London: Kegan Paul, Trench & Trübner, 1898.

Rossetti, Dante Gabriel. The Blessed Damozel. With an introduction by W. M. Rossetti. London: Duckworth, 1898.

The Savoy. 6 (October 1896).

The Yellow Book. 2 (July 1894).

Secondary

‘The Blessed Damozel.’The Art Journal, 1890: 288.

‘The Blessed Damozel.’ The Studio, 15 (1899): 289.

Chaucer, Geoffrey. The Canterbury Tales. London: The Kelmscott Press, 1896.

‘The Chronicle of Art.’ The Magazine of Art, 20–21 (1897): 170 –176.

‘Cuneo, Emma, and Sammy Hacker. ‘Critical Introduction to Volume 6 of The Savoy (October 1896).’ Savoy Digital Edition. Edited by Christopher Keep and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2018-2020. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2021. https://1890s.ca/savoyv6-critical-introduction/

‘The Fall of the Nibelungs.’ The Bookman, 13–14 (October 1897–March 1898: 107–108.

‘Fine Arts – The Book of Ruth.’ The Athenaeum, 3606 (5 December 1896): 801.

‘Fine Arts – The Fall of the Nibelungs.’ The Athenaeum, 3651 (16 October 1897): 531.

Malory, Thomas. Le Morte D’Arthur. Illustrated by Aubrey Beardsley. 2 Vols. London: Dent, 1894.

Steenson, Martin. ‘W. B. Macdougall.’ Studies in Illustration, 84 (Summer 2023): 35 –41.

Taylor, John Russell. The Art Nouveau Book in Britain. 1966; rpr. Edinburgh: Paul Harris, 1979.

Created 11 October 2024