John Martin (1789–1854) is best known as the artist of large, imposing paintings of mythological and Biblical scenes which characteristically include vast landscapes, crowds of anguished figures, tumultuous weather and scenes of earth-shattering, apocalyptic destruction. Drawing on imagery inspired by the wrecked countryside of the Industrial Revolution, which he transforms into a sort of intense, visionary dreaminess, Martin was always aware of what he wanted to do, noting in one of his catalogues that he appealed to thrill-seekers whose ‘mind is content to find delight in the contemplation of the grand and the marvellous’ and for whom he offered an endlessly expanding universe in which ‘the great becomes gigantic, and the wonderful swells into the sublime’ (qtd. Ray 44). In an age of uncertainty and anxious contemplation of what the future might hold, Martin played on a raw nerve.

In this role Martin was a crowd-pleaser who popularized Romantic attitudes to nature, offering his audience a more accessible rendering of the Sublime than was available in the work of his rival Francis Danby, and sometimes bore comparison with the art of Turner. But, unlike Turner, Martin was regarded with disdain by the establishment; never a member or even an associate of the Royal Academy, disparaged by the critics and dismissed by Ruskin as a manufacturer of effects rather than a visual poet, he remained an outsider despite (or perhaps because) of his popular success. Often likened to a showman – whose paintings were displayed in travelling exhibitions – Martin’s work was regarded by the art-loving elite as vulgar.

John Martin’s bizarre representation of the Apocalypse, The Great Day of His Wrath (1851–3).

His melodramatic excess was realized, moreover, in a style that many found coarse and untutored. Jeremy Maas sums up his apparent shortcomings in the eyes of his contemporaries, noting his weak ‘handling of paint’ and especially his ‘sense of colour, with its violent contrasts, its garishness, particularly in his use of blues and yellows’, along with ‘his treatment of foliage which looks like dried sponge [and his] his poor painting of figures, too often applied to the landscape like a cosmetic …’. Yet Maas acknowledges Martin’s imaginative qualities, recognizing that whatever his formal weaknesses he still excelled in creating an unparalleled impact and ‘sensation of awe’ (35) in the audiences that did appreciate his work.

Martin has always been the subject of detailed analysis, and recent exhibitions and the publication of a number of studies, notably by Michael J. Campbell and Martin Myrone, have reinstated his importance as a painter of excess and spectacle. In a time threatened by climate change and the destruction of the world is no longer so difficult to imagine, Martin’s apocalyptic, horror-struck imagery has regained its currency, and now seems menacingly prescient. The Last Man (1849) sums up his gloom, offering a more reflective image than usual as it contemplates a moment of valediction and finality with a single figure contemplating the end of life on Earth. As much like science-fiction as Romanticism, the painting has an existential resonance.

Martin’s melancholy reflection, painted in sombre tones, on the extinction of life and the final days of The Last Man (1849).

Martin as a Graphic Artist: Technique and Style

Many of Martin’s paintings were engraved on steel by copyists and sold as prints. A good example is The Last Judgement. But Martin also produced graphic art as original illustrations and series of illustrations. First of these was a series of 24 plates for Milton’s Paradise Lost (1824–27), which he followed up with 20 designs for the Bible (1831–5; 1838); he also designed a number of others, including images of dinosaurs for the palaeontologists Gideon Mantell and Thomas Hawkins.

Martin’s greatest success was Paradise Lost, a monumental book issued in monthly parts, in two volumes, in special editions and as two sets of free-standing prints. Gordon Ray describes the book as ‘of the great publishing enterprises of the age’ (44), and Martin’s work is unusual in being the only major set of cuts for a literary text produced using mezzotint, an etching technique more associated with painting than illustration. Commissioned by the American publisher Septimus Prowett, Martin’s undertaking was considerable, and Prowett rewarded him handsomely. For the first issue he paid the artist ‘an astonishing £2,000’, and for the second, made up of smaller images, he gave him £1,500 (Hodnett 111). This amount was an epic payment for an epic work, and the book was widely regarded at the time as a monumental venture. As noted in The Globe, Martin’s Paradise Lost projected a ‘style of sublimity and beauty, to which it may confidently be said, that the arts have hitherto produced nothing equal’ (Globe, 1827, 1).

The complexities of the edition’s style, development and production have been analysed in great detail, especially by Edward Hodnett, who writes at length of its strengths and weaknesses (107–36). Hodnett usefully explains the intricacies of producing a mezzotint:

Martin seems to have approached this black-to-white process by first etching his design in outline on a steel-plate [which lasted much longer than copper]. Then in the usual manner Martin pitted and burred the plate with a toothed ‘rocker’, The roughed surface held ink and printed an intense black. By scraping and burnishing in varying degrees, he produced subtle gradations of grey. Then by wiping the ink off the scraped or burnished areas, he got dazzling highlights. Sometimes … he added etched trees, foliage, and bits of outline … [Hodnett 111]

To master this process, Martin ‘set up a press in his home’ and taught himself how to do it; he studied each subject in oil and pencil sketches before he committed the design to the plate, but according to Hodnett he mostly ‘composed directly’ (112) onto the steel surface. The result, by and large, is impressive. Martin’s treatment of paint was subject to the charge of amateurishness, but his manipulation of the mezzotint process is a technical tour-de-force in which his contrasts of black and white are brilliantly managed. The effect recreates the crepuscular, menacing illumination of his paintings, and in practice Martin’s illustrations for Paradise Lost are miniaturized versions of his work in oil. Not only illuminated in the manner of his canvases, his designs for Milton are stylistically identical to those epic pieces, and deploy the artist’s characteristic visual motifs. Indeed, he treats the mezzotints as miniaturized compositions in oil: vast spaces made up huge landscapes and impossibly large buildings, deep recession, tiny figures picked out in light, tumultuous action and overbearing skies are as pronounced in the Milton series as they are in his large-scale creations, and generate the same tonal emphasis, a curious mix of the heroic and elevated, and the strange and sinister. We have only to compare The Last Judgement with the treatment of figure and space in The Courts of Heaven (Paradise Lost, 3: 365) to see the stylistic interchange between the two idioms.

Left: Martin’s extravagant, dream-like, unsettling treatment of The Last Judgement (1853). Right: Martin’s mezzotint, The Courts of God (1824–7).

In transferring his painterly imagery to the printed page Martin asserted a new seriousness in book illustration of the 1820s. That said, many of his contemporaries, such as Richard Westall, were illustrating in the manner of fine art; and the practice was commonplace in mid-Victorian and Pre-Raphaelite illustration, which recreated the aesthetics of oil and watercolour. Far from versatile, Martin illustrated in the only way he knew, and it would have been remarkable if his illustrations were radically different from his paintings. The key question, of course, is a simple one: Martin’s version of Paradise Lost is visually arresting, but are his designs, as etched paintings, effective illustrations?

Martin as an Illustrator of Paradise Lost

The answer must be a reserved and cautious one, with the artist achieving some insights into aspects of the text while failing to engage with others. Martin is highly effective in conveying the colossal scale of the physical settings in Milton’s poem, reproducing the terrible depth of Satan’s ‘bottomless’ (PL, 1: 47) fall, the ‘vast abyss’ (PL 1: 21) of creation, and the ‘fabric huge’ (PL, 1: 710) of Heaven, Hell and the Garden of Eden. Closely observing Milton’s lexicon of epic excess, Martin realizes the heroic magnitude in terms of the language of Burke’s Sublime, the ‘vastness beyond comprehension’ and ‘magnificence’ (qtd. Riding & Llewellyn) which generate awe and convey the power of titanic forces.

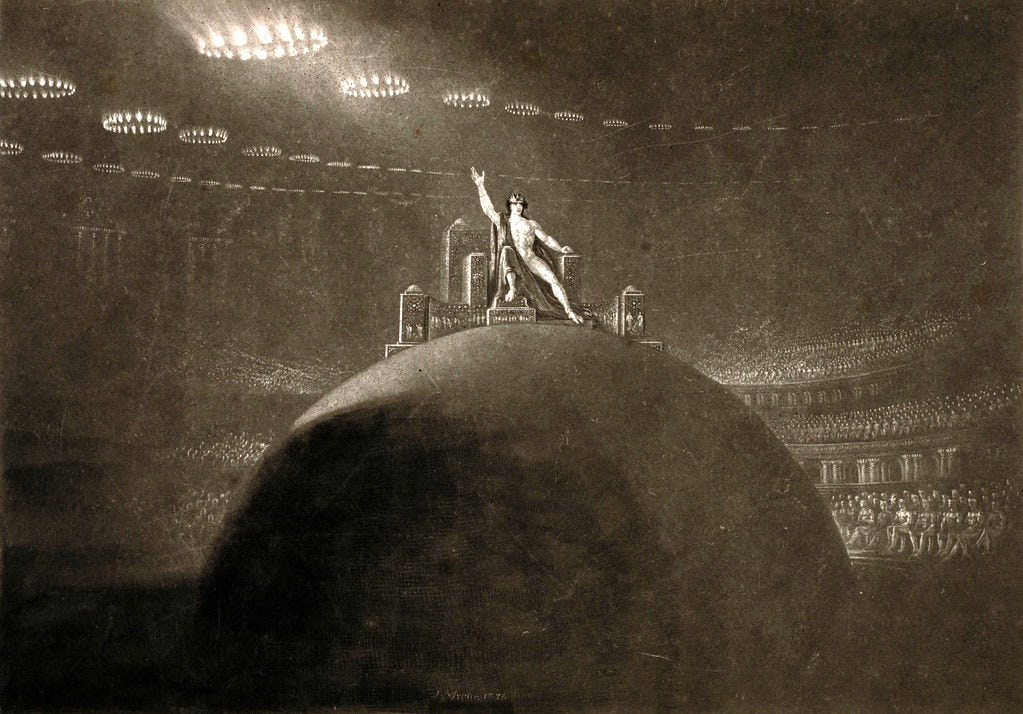

In The Courts of God and Pandemonium Martin visualizes the scale in terms of gigantic architecture that seems to reach out to infinity, while Eden is represented as lush, verdant domain of huge trees with vast mountains in the background. The most impressive design, perhaps, is Satan Presiding at the Infernal Council. This image visualizes the opening of Book 2:

High on a throne of a royal state, which far

Outshone the wealth of Ormus and of Ind …

Satan exalted sat by merit raised

To that bad eminence; and from despair

Thus high uplifted beyond hope, aspires

Beyond thus high, insatiate to pursue

Vain war with heaven … [1–9]

This is a moment of great dramatic power, and Martin interprets the lines in terms that are both faithful and inventive. He reproduces the throne and stresses the ‘bad eminence’ by placing Satan above a vast horde; he also endows him with signs of power missing from the text, dressing him in a toga and crown. Most impressive, however, is Martin’s invention of the huge globe on which the devil sits. Hodnett disapproves of this weird, dream-like device, noting how ‘Milton offers no hint of anything so sensational’ and dismisses ‘its symbolic meaning’ as a sign of the world (120–21). But Martin’s great globe must surely be read as a prefigurative emblem of Satan’s forthcoming ruination of Adam and Eve and announces his hegemony in the real world. It thus underscores the fatalism of the Biblical story and of Milton’s retelling of its narrative.

Martin, Satan Presiding at the Infernal Council (1824–7).

Martin is equally effective in representing the fundamental struggle between good and bad that underpins Milton’s epic poem. The illustrator visualizes this dialectic, as critics such as Beverley Sherry have observed, in terms of the interaction of light and dark, with Martin’s version of Miltonic ‘darkness visible’ (PL, 1: 63) symbolizing evil and light the power of Godly perfection, the state of grace and virtue. This visual metaphor is developed throughout the series, with ‘utter darkness’ (PL, 1: 48) contrasted with ‘transcendent brightness’ (1: 86) in the many scenes that represent the collision between the two states of being. In Satan Viewing the Ascent to Heaven, for instance, the character’s wickedness, imaged as absolute black, is measured against the intense, dazzling whiteness of heavenly illumination. The Courts of God and The Creation of Light are likewise zones in which light and dark struggle to assert superiority, and it is noticeable that the angels are always a source of brilliant, eye-jarring whiteness. The effect is impressive, constantly reminding the viewer of Milton’s ‘central concerns’ (Sherry 124) with right and wrong, and the conflict between them. The climax of the series, which depicts the Expulsion is an appropriate end, and here the metaphor is at its most resonant, showing the benighted couple evicted from Paradise with just a gleam of light behind them and briefly illuminating their bodies; in front of them is a landscape of absolute blackness, the image of the suffering and evil that is yet to come.

Left: Martin, Satan Viewing the Ascent to Heaven (1824–7). Right: Martin, The Creation of Light (1824–7).

Martin, Adam and Eve Driven Out of Paradise (1824–7).

Martin’s response to Paradise Lost might thus be described as an effective representation of the author’s primary themes. Technically brilliant, it articulates Milton’s messages in a series of visual equivalents in which the text’s meanings are inscribed in the workings of monumental landscapes and the interactions between the characters and their settings. As in his paintings, Martin invests the physical world with emotion, projecting his own version of Romantic nature in which the Sublime becomes the primary means of expression. As The Globe reviewer notes, he embodies ‘the stupendous and preternatural imagery of Paradise Lost’ (1).

Yet Martin’s focus has its contradictions too. Hodnett has written at length of what he sees as the illogical nature of some of his choices from the text (115–135), and concludes that the artist was lacking in consistency and sometimes failed to emphasise the main important moments. What is more striking, however, is the fact that in using landscape as the mode of expression the illustrator reduces the drama to the contemplation of tiny figures placed within vast spaces. Thomas Babington Macaulay was quick to notice this effect, commenting on the ways in which Martin reverses the effect of Milton’s poem, in which the characters are of central interest and the landscape is a symbolic background:

Those things which are mere accessories [in Paradise Lost] become the principal objects in his pictures; and those figures which are most prominent [in the poem] can be detected in the pictures only by a very close scrutiny. Mr Martin has succeeded perfectly in representing the pillars and candelabra of Pandemonium. But he has forgotten that Milton’s Pandemonium is merely the background to Satan. [qtd. Hodnett 113]

Of course, this cannot be taken as an absolute judgement, since Macaulay misunderstands the workings of the Romantic landscape as a register of emotion. But there can be no doubt that Martin’s treatment of the human cast undermines the integrity of the whole: tiny and insignificant, their impact is further negated by the weakness of his figure drawing and the artificiality of their melodramatic poses. In themselves, Satan, Adam and Eve are puppet-like, and all that matters in the settings in which they are placed. Martin’s illustrations must be read, in short, as epic images of titanic events in which the intimacy of the drama is sacrificed for its rhetorical impact.

Martin, Satan Tempting Eve (1824–7).

His art did not correspond with the growing taste for narrative and anecdotal paintings and illustrations as the impact of Romanticism receded, but Martin’s edition was popular throughout the early and mid-Victorian period. It was republished by Charles Tilt in 1837–8 and passed on to the publishers Henry Washbourne, Charles Whittingham, Bohn and Sampson Low, who between them kept the book in print until the mid-1860s; a version was also published by Appleton’s in America (1851).

Martin, the Bible, and Dinosaurs

The financial success of Paradise Lost encouraged Martin to plan two more monumental books representing the Bible in the form of the Old and New Testaments. He decided to publish these imprints himself, producing the first volume, entitled Illustrations of the Bible in parts in 1831–35. Surprisingly, it did not do well, although sales were better when it was reprinted by Tilt 1838; the New Testament series was abandoned.

In Illustrations of the Bible, which was made up of 20 mezzotints, Martin repeats the absolute contrasts of light and dark used in Paradise Lost and focuses, once again, on scenes of melodramatic excess and apocalyptic suffering and destruction. The Old Testament is of course a fertile source for his sort of religious imagery, enabling him to represent omnipotent power and its epic consequences; as in his paintings, so too in these illustrations the effect is one of brutal intensity. The Deluge, notably, shows anguished figures overwhelmed by an imploding world, and in The Destruction of Pharaoh the swirling waters are figured as part of a vortex – a motif that recurs throughout Martin’s work. In these designs, as in Paradise Lost, God’s authority, literally to make or break, is registered in the form of vast but malleable landscapes and skies that are either in the process of disintegration or seen at the very point of collapse. Animistic and rendered in plastic terms, Martin’s land/mindscapes are anything but reassuring, reminding us always of the petulant Jehovah of the Old Testament as he shapes and reshapes his recalcitrant creation.

Martin, The Destruction of Pharaoh (1831–5).

This epic key works well, and Illustrations of the Bible has the same visual impact as Paradise Lost. But, as in the case of the earlier work, Martin’s limitations are as apparent as his strengths. Always in a major chord, he is incapable of striking a minor one. Indeed, it is significant that he never worked on the proposed treatment of the New Testament, which demands a focus on intimate human drama, on kindness rather than destruction, on personal choice rather than punishment. Such a project would never fit with Martin’s particular talents, and it is unlikely he would have been able to shift the emphasis from landscape to the representation of plausible characters and their close-up interactions within the divine story. The usual explanation for his not doing this work is the failure of the first part, but it is more likely that he did not proceed because he realized it was outside his usual style and beyond his technical abilities.

Martin nevertheless produced a number of other projects with biblical themes, among them 11 etchings for Thomas Hawkins’s long poem, The Wars of Jehovah in Heaven, Earth, and Hell (1844); the title is enough to indicate the tenor of his illustrations, which were again produced in mezzotint. More surprising, given Martin’s focus on orthodox Christianity, is his work for the palaeontologists, Gideon Mantell and again for Thomas Hawkins. A proponent of traditional faith, he provided two pictorial frontispieces to promote the new body of learning. Each of these imagines the world of the dinosaurs. Martin opens Hawkins’s The Book of the Great Sea-Dragons (1840) with a scene of battling Plesiosaurs, and in Mantell’s The Wonders of Geology (1838) he depicts Iguanodons in a titanic struggle. Both designs point to the amorality of the primeval world, postulating an evolutionary world to replace the world of Illustrations of the Bible and Paradise Lost.

Martin, Fighting Iguanadons (1838).

Yet all of Martin’s works are linked by his fascination with change, destruction and suffering, of epic struggles enacted within a turbulent landscape that is animated by the workings of emotion or by the dictatorial impulse of a severe and unforgiving God. Shifting seamlessly from painting to illustration, Martin was a troubled, troubling, pessimistic visionary who, if limited in scope, was at least single-minded.

Related Material

Bibliography

Primary

Illustrations of the Bible. Published by Martin in parts in 1831–35 and republished by Tilt in 1838.

Hawkins, Thomas. The Book of the Great Sea-Dragons. With a frontispiece by John Martin. London: Pickering, 1840.

Hawkins, Thomas. The Wars of Jehovah in Heaven, Earth, and Hell. With a frontispiece by John Martin. London: Francis Baisler, 1844.

Mantell, Gideon. The Wonders of Geology. With a frontispiece by John Martin. 2 Vols. London: Relfe & Fletcher, 1838.

Milton, John. Paradise Lost. Illustrated by John Martin. London: Prowett, 1825–27. Issued in 12 parts and then published in 2 Vols.

Secondary

Campbell, Michael J. John Martin: Visionary Printmaker. York: York City Art Gallery, 1992.

Feaver, William. The Art of John Martin. Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 1975.

Hodnett, Edward. Image and Text: Studies in the Illustration of English Literature. Aldershot: Scolar, 1982.

Maas, Jeremy. Victorian Painters. London: Barrie & Jenkins, 1978.

Myron, Michael. John Martin. London: Tate Enterprise, 2013.

'Paradise Lost'.The Globe (19 March 1827): 1.

Ray, Gordon N. The Illustrator and the Book in England from 1790 to 1914. New York: The Pierpont Library, 1976.

Riding, Christine and Llewellyn, Nigel. ‘British Art and the Sublime.’ Tate Research Publication (January 2013). [On-line edition].

Sherry, Beverley. ‘John Martin’s Apocalyptic Illustrations to Paradise Lost.’ Milton and the Ends of Time. Ed. Juliet Cummins. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000. 123–143.

Created 15 October 2021