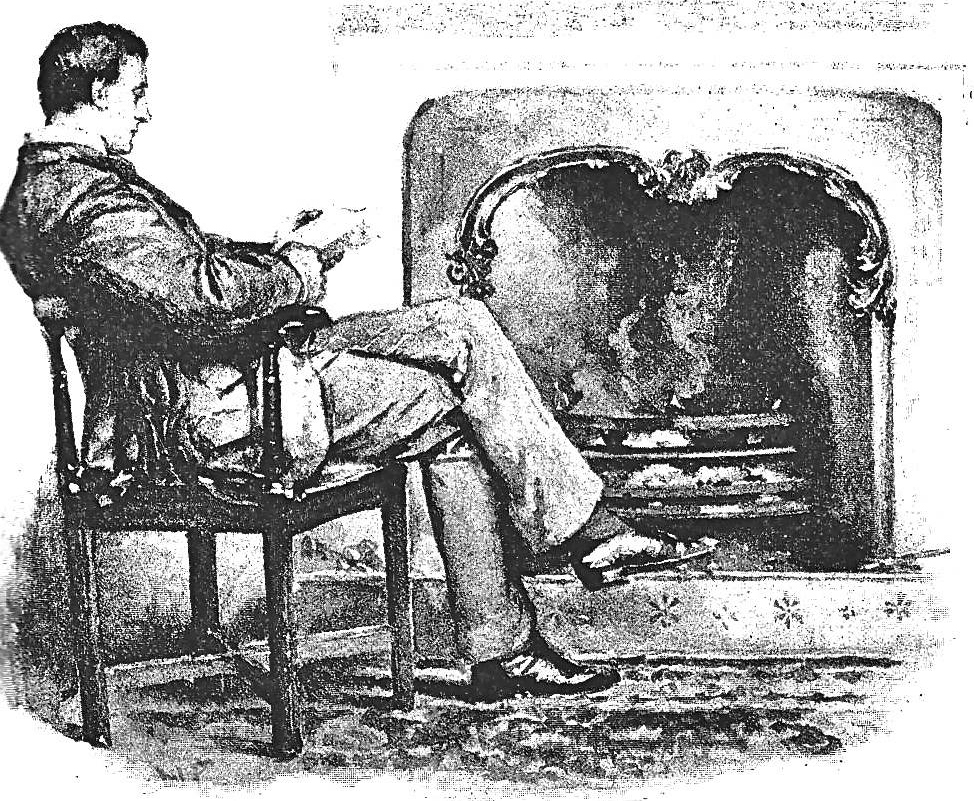

"It was a most charming little epistle", the second of Paget's the lithographic illustrations for Thomas Hardy's "On the Western Circuit," in the English Illustrated Magazine, December 1891, page 281. The ironic love-affair between London barrister Charles Raye and the illiterate Melchester maid, Anna, was later collected in Osgood, McIlvaine's Life's Little Ironies (1894).

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Introduced

The fact alone of its arrival was sufficient to satisfy his imaginative sentiment. He was not anxious to open the epistle, and in truth did not begin to read it for nearly half-an-hour, anticipating readily its terms of passionate retrospect and tender adjuration. When at last he turned his feet to the fireplace and unfolded the sheet, he was surprised and pleased to find that neither extravagance nor vulgarity was there. It was the most charming little missive he had ever received from woman. To be sure the language was simple and the ideas were slight; but it was so self-possessed; so purely that of a young girl who felt her womanhood to be enough for her dignity that he read it through twice. Four sides were filled, and a few lines written across, after the fashion of former days; the paper, too, was common, and not of the latest shade and surface. But what of those things? He had received letters from women who were fairly called ladies, but never so sensible, so human a letter as this. He could not single out any one sentence and say it was at all remarkable or clever; the ensemble of the letter it was which won him; and beyond the one request that he would write or come to her again soon there was nothing to show her sense of a claim upon him.

To write again and develop a correspondence was the last thing Raye would have preconceived as his conduct in such a situation; yet he did send a short, encouraging line or two, signed with his pseudonym, in which he asked for another letter, and cheeringly promised that he would try to see her again on some near day, and would never forget how much they had been to each other during their short acquaintance. — Chapter 3, p. 281.

Commentary

The social dimension of a romantic liaison intrudes at the close of the letterpress. The wife who will tend Raye's home and hearth (depicted in Paget's second illustration, p. 281) will not be the woman with whom over a number of months he has contracted an intellectual and emotional "bond" (288) through increasingly intimate correspondence that he would never have engaged in, had Anna not sought her mistress's assistance. At the close of the story, the smug Raye in his study depicted here becomes man enough to own up to his responsibility in seducing the simple maid. He recognizes ironically that his own unworthy actions stemming from his seduction of a naive village girl and not the correspondence composed by her employer have "ruined" him professionally and socially. As in the letterpress, in the final illustration Raye fulfills Edith Harnham's romantic yearnings, the picture if taken out of context suggesting a mutual emotional fulfilment, foiling the Hardyesque imagery in which Raye, "the fastidious urban" (288) regards himself as chained metaphorically, like a galley slave, to labour at the oar for the remainder of his life alongside "the unlettered peasant." He pays a steep price for the momentary gratification of lust under an assumed identity.

Additional Resources on Hardy's Short Stories

References

Brady, Kristin. The Short Stories of Thomas Hardy. London and Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1982.

Cassis, A. F. "A Note on the Structure of Thomas Hardy's Short Stories." Colby Library Quarterly 10 (1974): 287-296.

Gilmartin, Sophie, and Rod Mengham. Thomas Hardy's Shorter Fiction: A Critical Study. Edinburgh: Edinburgh U. P., 2007.

Hardy, Thomas. Life's Little Ironies, A Set of Tales, with Some Colloquial Sketches Entitled "A Few Crusted Characters". Illustrated by Henry Macbeth-Raeburn. Volume Fourteen in the Complete Uniform Edition of the Wessex Novels. London: Osgood, McIlvaine, 1894, rpt. 1896.

Hardy, Thomas. "On the Western Circuit." The English Illustrated Magazine. December 1891, pages 275-288.

Jackson, Arlene M. Illustration and the Novels of Thomas Hardy. Totowa, New Jersey: Rowman and Littlefield, 1981.

Johnson, Trevor. "Illustrated Versions of Hardy's Works: A Checklist, 1872-1992." Thomas Hardy Journal 9, 3 (October, 1993): 32-46.

Millgate, Michael. Thomas Hardy: A Biography Revisited. Oxford: Oxford U. P., 2004.

Page, Norman. "Hardy Short Stories: A Reconsideration." Studies in Short Fiction 11, 1 (Winter, 1974): 75-84.

Pinion, F. B. A Hardy Companion. Trowbridge, Wiltshire: Macmillan, 1968.

Purdy, Richard L. Thomas Hardy: A Bibliographical Study. Oxford: Clarendon, 1954, rpt. 1978.

Quinn, Marie A. "Thomas Hardy and the Short Story." Budmouth Essays on Thomas Hardy: Papers Presented at the 1975 Summer School (Dorchester: Thomas Hardy Society, 1976), pp. 74-85.

Ray, Martin. Chapter 22, "'On the Western Circuit'." Thomas Hardy: A Textual Study of the Short Stories. Aldershot: Ashgate, 1997. Pp. 201-217.

Wright, Sarah Bird. Thomas Hardy A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts on File, 2002.

Last modified 17 March 2018