The Denunciation

Phiz

Dalziel

December 1856

Steel-engraving

15.3 cm high by 9.9 cm wide, vignetted, facing 290 in volume

The Spendthrift, first published in Bentley's Miscellany, Part 18 (Chapters 45-50). The Routledge volume appeared shortly after this instalment, as the final number appeared.

[Click on image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Textual Background: Fairlie Denounced and Shamed before his Guests

"I am glad you have put up your pistol, sir," Fairlie said, abjectly, and cowering like a beaten hound before the other. "If you ave anything to say to me, I shall be happy to hear you — not now — but at a more convenient opportunity."

The present opportunity will serve for all I have to say to you," Monthermer rejoined, with ineffable scorn; "and let those who hear me mark my words, though your character is sufficiently well known to most of them. I denounce you as a knave and villain. Not only have you been guilty of foul ingratitude to your benefactor, my father, who raised you from the menial position to which you originally belonged, and took you into his confidence — a confidence whic you shamefully betrayed — but you have committed a fraudulent act in suppressing his last will, and substituting one of earlier date, which answered your purposes better, inasmuch as, by constituting you my guardian, it placed me in your power." [Chapter XLVIII, "The Denunciation," 289-90]

Commentary: The Duplicitous Steward Unmasked

"But now that you have assumed the rule and governance of the Castle, Fairlie, allow me to offer one suggestion, Have that portrait removed."

And as he spoke [Brice Bunbury] pointed to a full-length portrait of Warwick de Monthermer suspended over the chimney-piece.

"The old squire," Brice continued, "doesn't seem to look upon any of us with a very friendly eye, and he evidently regards you as an intruder." [Chapter XLVIII, "The Denunciation," 288]

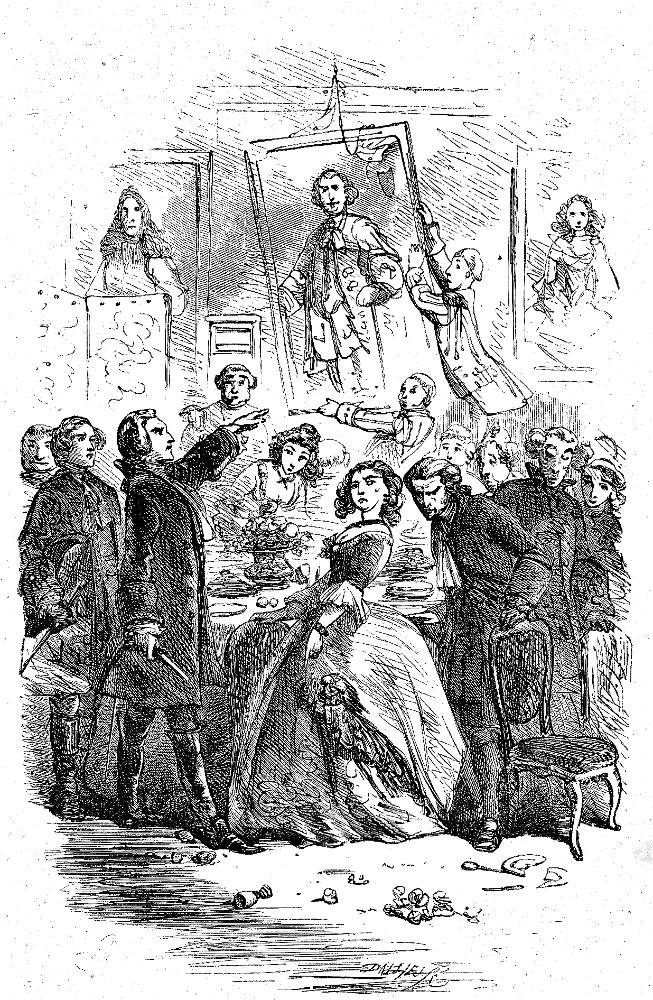

Thus, Phiz has created a triangular composition, with the early eighteenth-century portrait as the apex, and the principal figures of the text as its base — left to right: Rougham, Poynings, Gage Monthermer (arm raised, to draw the reader's eye upward to the point of contention, the paternal portrait), the cagey actress, Mrs. Jenyns, and the cunning steward, Fairlie (not much resembling Phiz's earlier portrait of him in Mrs. Jenyns taking a peep into Fairlie's Box), and the callous wit and Fairlie's unscrupulous supporter, Brice Bunbury. Fairlie, supported by Bunbury, plays hosts to his guests in the Monthermer family's castle he has just acquired by guile. Suddenly the young squire himself, Gage Monthermer, attended by Arthur Poynings and Mark Rougham, arrives just as Fairlie has ordered the servants to remove the full-length portrait of Warwick de Monthermer, who seems to scowl down at the usurping steward, Fairlie, disapprovingly. The three young men have resolved to terminate the rascal Fairlie's occupation of the Monthermer family seat. The "Spendthrift" and gambler Gage Montherner, the real master of the house, pistol in hand, orders the servants to stop taking down his father's portrait as the elegantly dressed actress, Mrs. Jenyns, turns to the man whom she had thought to marry, the skulking Fairlie (right), behind the chair. Fairlie had fancied himself the new lord of the castle based on his having foreclosed on Monthermer's debt, but he has not anticipated his adversary's arrival and opposition. The scene underscores Ainsworth's feelings of regret that the political power and social influence in nineteenth-century Britain had passed from the aristocracy to the rising middle classes. This lamenting the passing of the old order Phiz comments upon by placing a cobweb conspicuously above the portrait that the liveried servants are in the process of removing.

Technically, although Phiz has entitled the plate "The Denunciation," this extended speech does not properly belong to the illustration since Gage Monthermer has clearly just entered the castle's dining-room and still has his pistol out, and Fairlie is not yet "cowering." Thus, Phiz has deployed his engraving as signifying that the protagonist is about to to denounce his father's perfidious steward, and reveal the plot regarding substitution of wills. This typically Ainsworth plot-gambit will thoroughly inform the last part of Mervyn Clitheroe in the second phase (December 1857-June 1858), the writing of which, much delayed, Ainsworth took up again about a year after completing The Spendthrift in November 1856. Ainsworth, incidentally, revealed a nice sense of bourgeois marketing as he brought out the Routledge volume edition just in time for the Christmas book trade. Although this is the last illustration, Ainsworth still has a few significant plot revelations to deliver as a deus-ex-machina:

Goaded on by his rascally steward Fairlie, who grows rich at his young master's expense, Gage de Monthermer ruins himself by gambling and extravagant living. Just as he is about to displace Gage completely, Fairlie has a change of heart consequent on the death of his daughter Clare, and, shortly before he himself dies, restores his fortunes to the penitent and reformed Gage. [Worth, 119]

Working methods

- "Phiz" — artist, wood-engraver, etcher, and printer

- Etching, Wood-engraving, or Lithography in Phiz's Illustrations for A Tale of Two Cities?

Bibliography

Ainsworth, William Harrison. The Spendthrift: A Tale. (1860). Illustrated by Phiz; engraved by the Dalziels. Ainsworth's Works. London & New York: George Routledge, 1882.

Buchanan-Brown, John. Phiz! Illustrator of Dickens' World. (1860). New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1978.

Lester, Valerie Browne. Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens. London: Chatto and Windus, 2004.

Vann, J. Don. "The Spendthrift in Bentley's Miscellany, January 1855 — January 1857." Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: Modern Language Association, 1985. 30.

Worth, George. William Harrison Ainsworth. New York: Twayne, 1972.

Victorian

Web

Illustra-

tion

The

Spendthrift

Phiz

Next

Created 29 December 2019

Last modified 12 May 2020