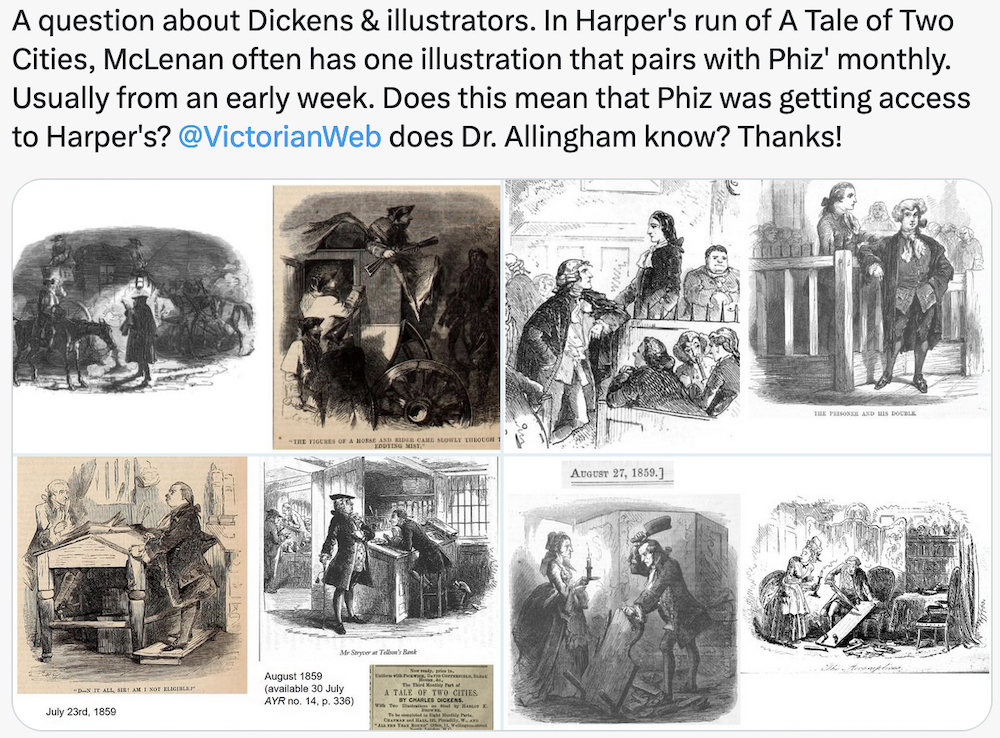

A question about Dickens & illustrators. In Harper's run of A Tale of Two Cities, McLenan often has one illustration that pairs with Phiz's monthly, usually from an early week. Does this mean that Phiz was getting access to Harper's? [Christian Lehmann]

Some superficial resemblances, but....

The long and short of the problem raised by the correspondent is that Dickens provided Harper and Brothers in New York with proofs of the All the Year Round numbers so that their house artist, John McLenan, could see the text as rapidly as possible and so that Harper's printers could set up the weekly number in type. But Harper & Bros. did not send their proofs back to Dickens. And I am not even sure whether McLenan even saw the British proofs.

Even with access to the American weekly numbers (which were a week behind the All the Year Round schedule, and would have taken almost two weeks to get from New York to London), only a few instances of "influence" on Phiz's program are possible. And as far as I know, Dickens made no arrangement with his New York publishers to receive weekly instalments of A Tale of Two Cities as these were published in Harper's Weekly from 7 May through 26 November 1859. I therefore regard the resemblances between the two versions of The Accomplices (October 1859) for example as serendipitous. Since the American newspaper serial contains thirty instalments with two illustrations each, some overlap was inevitable: Phiz has only sixteen in total, and he had to produce six of these for November-December 1859 monthly seriaisation well ahead of the volume publication by Chapman and Hall on 5 November 1859.

We can assume that Phiz had already read the All the Year Round instalments before starting to work on the paired monthly illustrations for the June number. He had read at least the first two weekly instalments in Dickens’s weekly before starting The Mail and The Shoemaker. If he had seen John Mclenan’s illustrations for Harper's Weekly (which I strongly doubt since British copyright kept American publications out of Britain), he might possibly have been influenced by the American’s May 7th illustrations only. (Transatlantic shipping required at least ten days in the autumn of 1859.) One of these Harper’s wood-engravings is an inferior version of The Mail, and the other a somewhat fanciful version of Dr. Manette’s being released from the Bastille by an angel holding keys. As the monthly serial in Britain ran June through November 1859, if Phiz had a reliable way of getting copies of Harper’s Weekly Journal in a timely fashion, one would expect that the September through November plates might have represented his artistic response to the McLenan plates. The volume edition of early November 1859 contains Phiz’s December plates, so it is reasonable to assume that those four plus the frontispiece and vignette were completed in October, but Phiz could not have seen Mclenan’s Harper’s woodcuts for anything beyond Book Three, Chapter Seven. Consequently, if one wishes to argue that Mclenan’s work influenced Phiz’s, one would have to consider May 7 (the first Harper’s instalment) through the twenty-second, a total of forty-four wood-engravings. Within that acceptable range of “influence” one does indeed see some overlap: McLenan 3.2 dates from 21 May 1859, and could have arrived in London at the end of May — too late to have influenced Phiz in The Shoemaker (which was published in June 4, but which was probably drawn and engraved perhaps three weeks earlier, say May 14 at the latest). The Shoemaker from the initial monthly number does indeed rudimentarily resemble either the Harper’s "A white-haired man sat on a bench, stooping forward and very busy, making shoes" (21 May 1859) or “He took her hair into his hand again, and looked at it closely” (28 May 1859), but Phiz must have drawn his version two or three weeks earlier, and was therefore relying on the unillustrated instalments in All the Year Round (30 April and May 7). The correspondent has, I notice, focussed on the similarity between Phiz’s The Likeness (July instalment) and The Prisoner and his double (11 June 1859 in the New York weekly), but if Phiz had access to Harper’s he would have to have seen that illustration in mid-May at the latest: not possible. Other “pairs” might include The Wine Shop and "And stood with his hand on the back of his wife's chair" (Harper’s, 13 August, and monthly for September 1859 in London), The Accomplices (Phiz, first Saturday in October; Harper’s, 27 August 1859, but not available to Phiz until mid-September), and Stryver at Tellson’s Bank (Harper’s, 17 September, and monthly August, 1859). In other words, transAtlantic shipping would largely have prevented Phiz from seeing the McLenan plates unless the American artist was directly providing him with proof drafts, which I find unlikely. Consider the limitations imposed by even the fastest ship:

Dickens and Kate sailed for Boston on the Britannia on 4 January 1842. Steam was still as much a novelty on sea as on land: only two other British paddle-steamers had crossed the Atlantic before the maiden voyage of the Britannia in 1840. . . . if all went well it was fast. The steamers could make over eight knots and reach Boston in about eighteen days. [Norman and Jeanne MacKenzie, 109]

Accordingly, I conclude that the correspondent had an interesting idea about near-simultaneous publication and possible collaboration between the serial illustrators in New York and London, but failed to take into account the actual publication schedules and the problem of the transAtlantic crossing. By 1867 and the second reading tour, Dickens crossed from Liverpool to Boston on the steamship Cuba in just ten days (Norman and Jeanne MacKenzie, 357), much faster than he and Catherine had in 1842, but still not fast enough to facilitate a collaborative relationship between the American and British serial illustrators.

Related Materials

- A Tale of Two Cities: An Overview (Sitemap)

- The Plates

- Some Discussions of Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities

- A Note on Phiz's Wrapper Design for Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities (1859) in Monthly Serialisation

- John McLenan's illustration in Harper's Magazine (USA)

- 25 Illustrations for Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities by Fred Barnard (from the household Edition, 1874)

- Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s Diamond Edition illustrations for A Tale of Two Cities (1867)

- A. A. Dixon's illustrations for A Tale of Two Cities (1905)

- Harry Furniss's illustrations for A Tale of Two Cities (1910)

Scanned images, colour correction, sizing, caption, and commentary by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose, as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.] Click on the image to enlarge it.

Bibliography

Allingham, Philip V. "'Charles Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities (1859) Illustrated: A Critical Reassessment of Hablot Knight Browne's Accompanying Plates." Dickens Studies. 33 (2003): 109-158.

Browne, Edgar. Phiz and Dickens As They Appeared to Edgar Browne. London: James Nisbet, 1913.

Cayzer, Elizabeth. "Dickens and His Late Illustrators. A Change in Style: Phiz and A Tale of Two Cities." Dickensian 86, 3 (Autumn, 1990): 130-141.

Cohen, Jane R. "Part Two. Dickens and His Principal Illustrator. Ch. 4. Hablot Browne." Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: University of Ohio Press, 1980. 61-124.

Cunnington, C. Willett and Phyllis. Handbook of Eighteenth Century. London: Faber and Faber, 1972.

Cunnington, Phyllis. Handbook of English Costume in the Nineteenth Century. Boston: Plays, 1970.

Dickens, Charles. (1859). A Tale of Two Cities, ed. Andrew Sanders. World's Classics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1980.

________. A Tale of Two Cities (1859), ed. George Woodcock. Illustrated by Phiz (Hablot Knight Browne). Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1970.

Hammerton, J. A. The Dickens Picture-Book. The Charles Dickens Edition of the Works of Charles Dickens. London: Educational Book, 1910.

MacKenzie, Norman and Jeanne. Dickens: A Life. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1979.

Created 8 April 2023