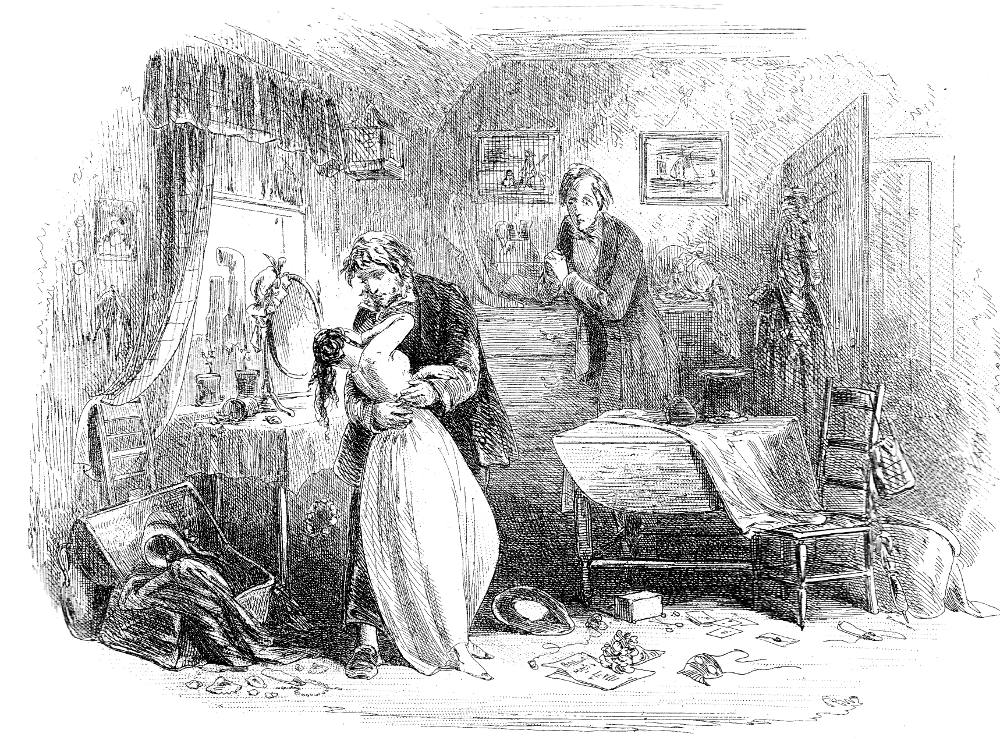

Mr. Peggotty's dream comes true by Phiz (Hablot Knight Browne). August 1850. Steel etching. Illustration for Chapter L, "Mr. Peggotty's Dream comes true," in Charles Dickens's David Copperfield. Source: Centenary Edition (1911), Volume Two, facing page 344. 10.6 x 14.5 cm (4 ¼ by 5 ⅝ inches), vignetted. [Return to text of Steig. Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Commentary

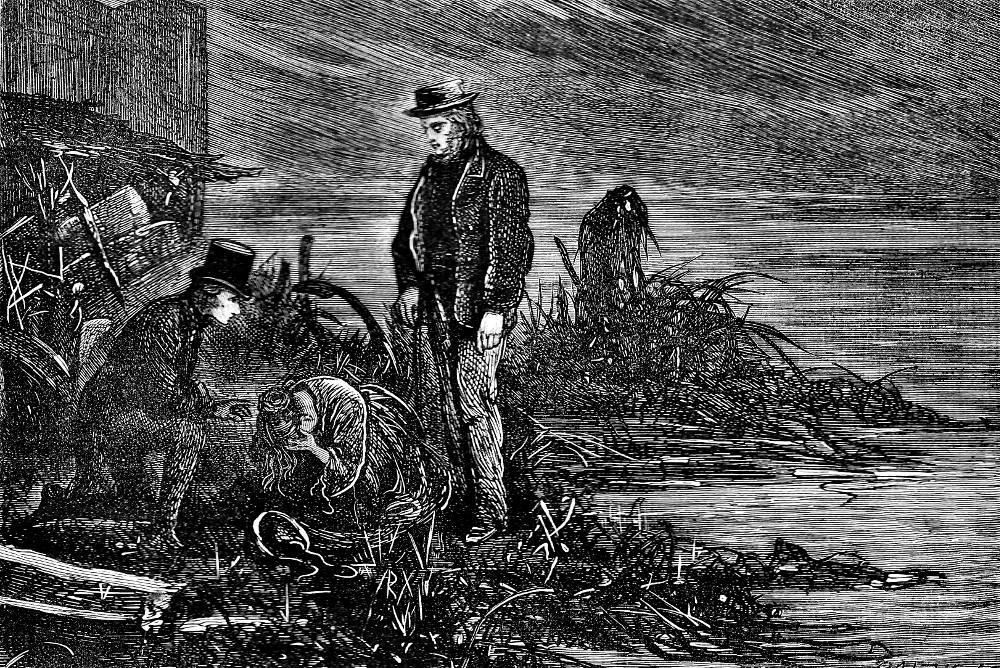

The second illustration for the sixteenth monthly number, issued in August 1850, complements the last of the four chapters (47 through 50) in this instalment, the title of the plate being identical to the chapter title except for the latter's capitalisation of "Dream." For the first illustration, Phiz had chosen to realize Mr. Peggotty's and David's interrupting Martha as she contemplates committing suicide by drowning herself in the Thames. In this second August 1850 illustration, the two men again intervene, this time rescuing Em'ly from a life of degradation and an early death that was the inevitable fate of London prostitutes in the Hungry Forties. Just as Trotty Veck in The Chimes six years earlier had realized his most cherished hope, awakening from a nightmare marked by incendiarism, prostitution, and suicide by drowning to see his daughter "recalled to life," so here Mr. Peggotty at last reclaims his beloved niece after years of searching in vain. The picture resolves this strand of the plot while simultaneously delaying our apprehending Mr. Micawber's disclosure of the full extent of Uriah Heep's villainy. According to J. A. Hammerton (1910), the illustration depicts the following passage:

"Mas'r Davy," he said, in a low tremulous voice, when it was covered, "I thank my Heav'nly Father as my dream's come true! I thank him hearty for having guided of me, in His own ways, to my darling!"

With these words he took her up in his arms. . . . [Vol. 2, 345].

Phiz has been unable in the illustration to convey the text's sense that Dan'l Peggotty regards himself as God's agent in Em'ly's reclamation. Rosa Dartle has repeatedly insulted and vilified Em'ly, and David has continually wished for her uncle's arrival: finally, he comes as Rosa departs. To intensify the exquisitely melodramatic moment, Phiz has turned the anguished girl's face away from the viewer (leaving the viewer to imagine her expression) as she twists in her uncle's embrace, as if trying to tear herself away in shame. Drawing our attention to the telling background details in this theatrical backdrop, Michael Steig in Dickens and Phiz comments upon a number of parallels between this iteration of the "fallen woman" (here, redeemed, and therefore clothed in white) and Phiz's exemplification of the same topos of the fallen or lost woman, in his illustration for chapter 22. Thus, through the poses and embedded details that are his hallmark Phiz reveals that he clearly understood that Em'ly is Martha's double, another reification of the social problem that so absorbed the philanthropical Dickens at this time as he worked with banking heiress Angela Burdett-Coutts to establish a training centre and refuge for reformed prostitutes at Shepherd's Bush, suburban London, which they appropriately dubbed "Urania Cottage" when they opened this charitable institution in 1847.

The rescue of Martha from the river is followed in the text by the rescue of Emily from prostitution, and so in the illustrations. Mr. Peggotty's dream comes true (ch. 50) was apparently a bit uncertain in the making, as the drawing (Elkins) suggests; in it not only does David wear a hat, but a female figure seated in the chair and slumped over the table is probably intended for Rosa Dartle, who has been haranguing Emily when the two men enter. The drawing (Elkins), which is reproduced in Kitton, Dickens and His Illustrators, fac. p. 84), is an awkward version, but it is understandable that Phiz should have included Rosa, since the text itself fails to indicate whether she managed an exit before the end of the chapter. Parallels to other plates are numerous. First, Emily recalls the main, kneeling figure of Martha, whose face is similarly hidden. Then there are conventional allusions to Emily's lost innocence in the broken flowerpot, cracked mirror (into which she seems to be looking as her uncle holds her), and broken pitcher; Rosa's remark that Emily must "drop her pretty mask" — that is, be the prostitute that Rosa considers her, instead of the wronged woman she thinks herself — is rather awkwardly reflected in the domino mask and masked-ball program, since Emily surely has not come from a party, although perhaps these items are to be taken literally as the leavings of a previous, disreputable occupant.

From another point of view than Rosa's, however, the dropping of the mask might represent Emily's return from her pose as mistress of a grand gentleman to her real self, emblematized in the signs of her cherished past and happier future: the seashells that have fallen from her trunk, mementoes of her beloved home, the picture of a fisherman and a little girl, and that of a ship sailing on fair seas. This last may have its origin in the text's reference to "common pictures of ships on the walls," but recalling that in an earlier illustration Emily's fate has been foreshadowed by a picture of a ship in a storm, it is likely that the present one refers to her future, when she is happily reunited with her uncle. [Steig 128-129]

Whereas David and Mr. Peggotty are in the background in "The River," with the figure of Martha in sharp relief, here David, his hat resting on the disturbed tablecloth of the drop-leaf table (right), is up-centre, a distraught audience to the event unfolding before him in a disordered room that is the outward and visible sign of Em'ly's emotional distress, although in fact, as the text makes clear, this flat is being rented by Martha. The scene is a crescendo of emotion, of guilt, compassion, and forgiveness, occurring at the very end of the sixteenth instalment, signalling that in each monthly number from now on one strand of the plot will be brought to closure. Although published in early August, this scene was radically re-written at the end of July, giving the illustrator little time to make the necessary adjustments since Rosa Dartle was originally in the scene and David accompanied by Mr. Peggotty. As the scene now stands, Rosa has just departed and Mr. Peggotty has just arrived, with David as the first-person narrator hidden with Martha throughout.

Phiz has taken the detail of the pictures of sailing ships on the walls of Martha's room ("some common pictures of ships," p. 339) from the text. Everything else in the room has come from the artist's imagination, except the chair, table, and open door. The room itself is located in the vicinity of Golden Square, between Regent and Great Windmill Streets, a decidedly "low" area not far from the Haymarket, where prostitutes in legions plied their trade after dark in that decade. The room, therefore, should not be nearly so well furnished, let alone full of symbols such as the mask from a masked ball more fitting for the "kept woman" Em'ly than for Martha, especially if the mask implies Em'ly's having deceived Steerforth with an appearance of innocence rather than her having attended such an event with Steerforth in Venice, perhaps. The chief disparity, however, is the absence of David's companion, Martha, and David's being in the room, rather than merely "looking in" (345) from the little garret beyond.

"David's horrified yet compassionate expression as he watches Peggotty comfort his niece suggests he may at last have gone beyond mere sight to insight" (Cohen 107). He is no longer the passive observer looking about him in a detached manner as in Our pew at Church. David has emerged from the shadows in The River to engage himself mentally and emotionally with those whom he observes, reports upon, and analyses. He no longer re-enacts the role of the detached, clinical observer that Mr. Murdstone modelled for him all those years ago. Perhaps David's ghastly look, shocked expression, and the agitated hands betoken a recognition of the fate that Dan'l Peggotty's compassion have averted for his niece, whose tangled hair and curved body echo the posture of shame and self-loathing seen in the character of Martha in The River. However right Cohen may be in her analysis of the postures of the scene's figures, she is incorrect in identifying the contents of the room with elements from Em'ly's Yarmouth past exclusively:

In this scene, entitled with sad irony Mr. Peggotty's Dream comes true, Browne fills her shabby room with pictures alluding to her past — of small children, a fisherman, a ship — and objects alluding to her lost virginity: the broken ewer, cracked mirror, smashed flower pot, empty envelope, discarded dance program, single dancing slipper, and abandoned bonnet and purse (like Martha's in the earlier scene). [Cohen 106-107]

The cherished "past" exemplified by these tokens is one which the Yarmouth seamstresses Em'ly and Martha share, a past rooted in small town, labouring class values, a sense of community, a close-knit family, from all of which society has excluded both of them because of their moral and sexual lapse. Thus, the objects in the room constitute Browne's special pleading for compassion for those who, after all, had worthy aspirations, joyful childhoods, and loving families. Em'ly in particular is somebody's child, somebody's sweetheart, somebody's childhood companion, rather than merely a ruined woman with a sordid past. The objects, then, plead against the viewer's accepting the moral judgment of Rosa Dartle, speaking from the judgment seat of upper-middle-class respectability.

Scenes Associated with the Restoration of Little Em'ly to Her Family (1872 and 1910)

Left: Fred Barnard's Household Edition build-up towards this scene:

Related Resources

- The Remains of the Day: Death and Dying in Victorian Illustration

- O. C. Darley's Frontispiece in the New York edition (Vol. 1, 1863)

- O. C. Darley's Frontispiece in the New York edition (Vol. 2, 1863)

- O. C. Darley's Frontispiece in the New York edition (Vol. 3, 1863)

- Sol Eytinge, Junior's 16 Diamond Edition Illustrations, Vol. IV (1867)

- Fred Barnard's 62 Illustrations for the British Household Edition (1872)

- Harry Furniss's Frontispiece David Copperfield for the Charles Dickens Library Edition (1910)

- Kyd's six Player's Cigarette Card watercolours (1910)

Image scan and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Cohen, Jane Rabb. Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus, Ohio: Ohio U. P., 1980.

Dickens, Charles. The Personal History of David Copperfield, illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ("Phiz"). The Centenary Edition. London & New York: Chapman & Hall, Charles Scribner's Sons, 1911.

Hammerton, J. A., ed. The Dickens Picture-Book: A Record of the Dickens Illustrations. London: Educational Book, 1910.

Kitton, Frederic G. Dickens and His Illustrators. 1899. Rpt. Honolulu, Hawaii: U P of the Pacific, 2004.

Steig, Michael. Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington & London: Indiana U. P., 1978.

Created 7 February 2010 Last modified 19 March 2022