A City Personage

1868

12.4 x 8.7 cm framed

Facing page 104 in the Illustrated Library Edition

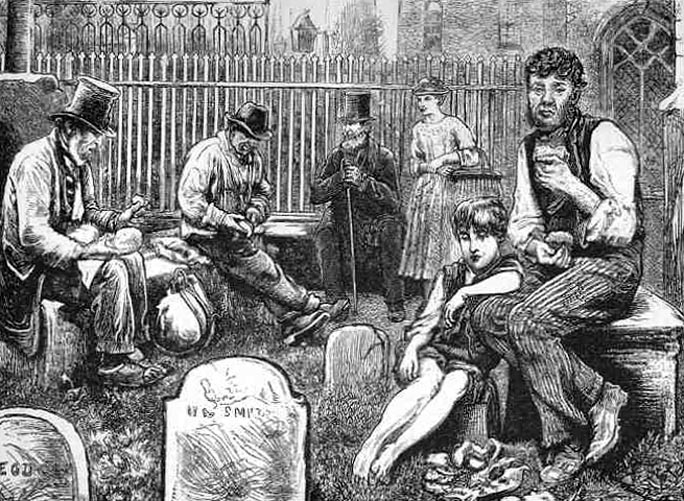

In the second of the four Pinwell Illustrations — which the 1893 reprint of the Illustrated Library Edition by Chapman and Hall has mistakenly attributed to Marcus Stone — George Pinwell reveals his capacity for visual story-telling. Like the large-scale and smaller, more intimate oil paintings of such seventeenth-century Dutch masters as Vermeer and Rembrandt, Pinwell's wood-engraving here focusses on a relationship between several characters, and challenges the viewer to construct their story. [Commentary continued below.]

[Click on image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Illustrated

In one of these City churches, and only in one, I found an individual who might have been claimed as expressly a City personage. I remember the church, by the feature that the clergyman couldn't get to his own desk without going through the clerk's, or couldn't get to the pulpit without going through the reading-desk I forget which, and it is no matter and by the presence of this personage among the exceedingly sparse congregation. I doubt if we were a dozen, and we had no exhausted charity school to help us out. The personage was dressed in black of square cut, and was stricken in years, and wore a black velvet cap, and cloth shoes. He was of a staid, wealthy, and dissatisfied aspect. In his hand, he conducted to church a mysterious child: a child of the feminine gender. The child had a beaver hat, with a stiff drab plume that surely never belonged to any bird of the air. The child was further attired in a nankeen frock and spencer, brown boxing-gloves, and a veil. It had a blemish, in the nature of currant jelly, on its chin; and was a thirsty child. Insomuch that the personage carried in his pocket a green bottle, from which, when the first psalm was given out, the child was openly refreshed. At all other times throughout the service it was motionless, and stood on the seat of the large pew, closely fitted into the corner, like a rain-water pipe. [103-04]

Commentary

The piece which the illustration complements, "City of London Churches," first appeared in All the Year Round on 5 May 1860, recording the exploratory excursions that the novelist periodically made with his oldest son in the period from early 1848 through the autumn of 1851, when the Dickens family lived at Devonshire Terrace. In "City of London Churches," Michael Slater and John Drew remark, "The 'City Personage' and his child . . . appear to frequent All Hallows London Wall, which still possesses the inconvenience noted by the narrator" (106). Pinwell has introduced in the background two heads in a box-pew to suggest "the exceedingly sparse congregation," a marble monument of the type found in many a pre-nineteenth-century English church, and ornate wrought-iron railings, suggesting that he may have had a specific church interior as his model. The illustrator succeeds in rendering the "City personage" an enigmatic figure about whose purpose there and business background the reader, like Dickens's narrator, feels compelled to speculate, but cannot come to any definite conclusions.

Whereas C. S. Reinhart in his "And with his eyes going before him like a prawn's has furnished the American Household Edition reader with a somewhat stagey piece of physical and character comedy, G. J. Pinwell in the Illustrated Library Edition of the previous decade offers a study almost devoid of humour. Indeed, one could say that he takes both of his enigmatic subjects far more seriously and sympathetically than does Dickens as Pinwell compels readers to admire the personage for his solicitous care of the elegantly dressed little girl. However, like Dickens Pinwell causes the reader to wonder about a number of issues, including the relationship between the elderly bourgeois and the doll-like child, his occupation or vocation, the reason for his utterly ignoring the church service, — and the nature of the contents of the little bottle that he is giving her.

Of bibliographical interest is Pinwell's specifically dating the drawing "68" on the kneeling cushion, lower right. This dating coincides with F. G. Kitton's dating of the Library Edition (p. 220), as affirmed by Slater and Drew as their date for UT1, that is The Uncommercial Traveller (The Charles Dickens Edition) (Chapman & Hall, 1868). Slater and Drew subsequently give 1874 as the publication date for the "Library Edition, illustrated" (vii), noting that the other four illustrations by "W. M.," but attributed to Marcus Stone in the 1893 re-printing, first appeared in the 1874 Library Edition published by Chapman and Hall. This edition the Centenary Edition of 1911 incorrectly dates as 1875, a date commonly used by online booksellers.

Related Material

Household Edition Illustrations Associated with Churches in the Metropolis

Left: C. S. Reinhart's American Household Edition illustration "Time and His Wife" for "The City of the Absent"; right: E. G. Dalziel's British Household Edition illustration "Blinking old men who are let out of workhouses by the hour, have a tendency to sit on bits of coping stone in these churchyards" for "The City of the Absent" (18 July 1863).

Bibliography

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Books and The Uncommercial Traveller. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. Vol. 10.

Dickens, Charles. The Uncommercial Traveller. Illustrated by Marcus Stone [W. M., and George Pinwell]. Illustrated Library Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1868, rpt., 1893.

Dickens, Charles. Hard Times and The Uncommercial Traveller. Illustrated by Charles Stanley Reinhart. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876.

Dickens, Charles. The Uncommercial Traveller. Illustrated by Edward Dalziel. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1877.

Dickens, Charles. The Uncommercial Traveller. Illustrated by G. J. Pinwell and W. M. The Centenary Edition. London: Chapman and Hall; New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1911.

Schlicke, Paul, ed. "The Uncommercial Traveller." The Oxford Companion to Dickens. Oxford and New York: Oxford U. P., 1999. Pp. 100-101.

Slater, Michaell, and John Drew, eds. Dickens' Journalism: 'The Uncommercial Traveller' and Other Papers 1859-70. The Dent Uniform Edition of Dickens' Journalism, vol. 4. London: J. M. Dent, 2000.

Victorian

Web

Visual

Arts

Illus-

tration

George

Pinwell

Next

Last modified 20 August 2013