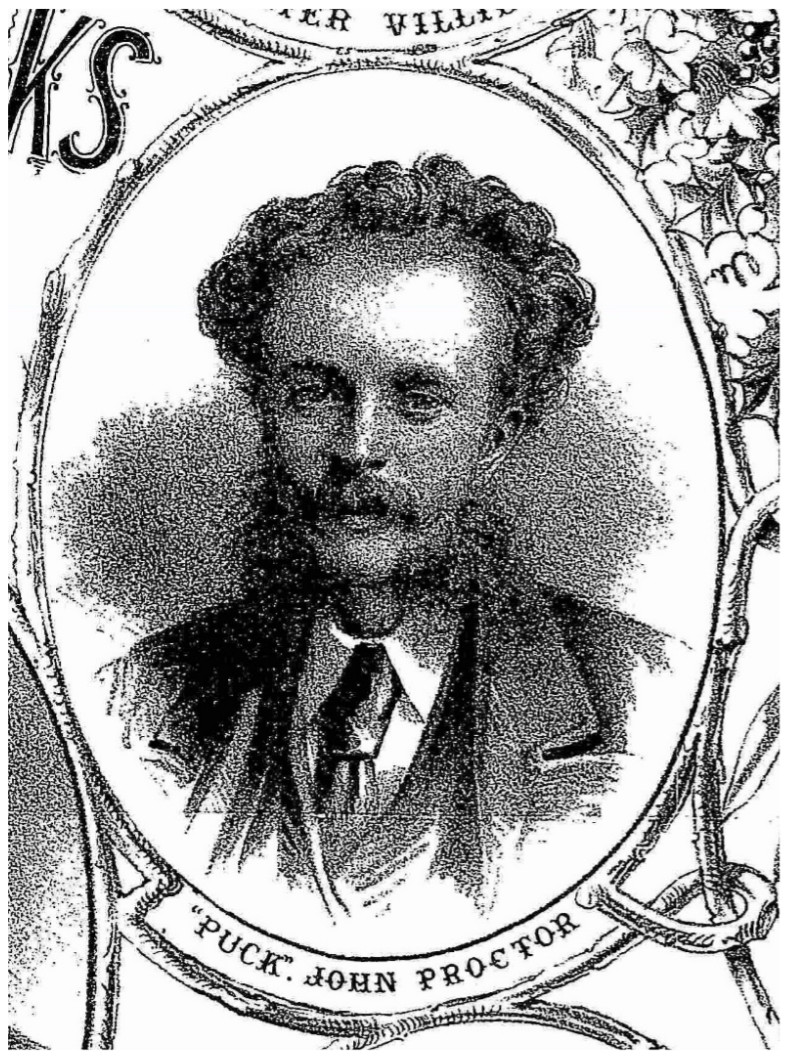

"'Puck.' John Proctor." Source: "Portrait Supplement to Our Young Folks' Budget," n.p. Christmas Number (19 December 1874).

John Proctor (1836-1914) was a prolific and peripatetic cartoonist, whose work appeared in a variety of comic magazines throughout the Victorian era. He served as chief cartoonist on the conservative weeklies Judy (1867-1868), Will O'The Wisp (1868-1869), Funny Folks (1874-1878), Moonshine (1881-1889), and (during its period of Liberal Unionism in the 1890s) Fun (1893-1889), as well as contributing illustrations to Our Young Folks' Weekly Budget (1870s), Sons of Britannia (1870s), and other publications.

Born in Edinburgh on 26 May 1836, Proctor was the son of a master plumber, and one of nine children (three of whom died young). Originally destined for a trade, Proctor's father Adam eventually became convinced that there was the potential for his son to pursue a career in art. Proctor was apprenticed to William Banks, the engraver, then found work with the publisher Thomas Nelson and Sons, before moving south to London in 1859. Proctor did some jobbing work for the Illustrated London News, and returned briefly to Scotland to marry in 1861 (he wed Harriet Joanna McCallum on 25 July 1861). Returning and settling in South London, Proctor joined Cassell, Petter & Galpin (later Cassell & Co.), and produced various frontispieces, illustrations, and other work for (e.g.), the Life of Christ, Dame Dingle's Fairy Tales (1865), and Bright Thoughts for the Little Ones (1866).

As well as working in book illustration, Proctor was able to supplement his income with work in the periodical press, contributing to The London Journal, Seven Days Journal, as well as collaborating with two other Scots on the short-lived Empire weekly journal (which failed around 1867).

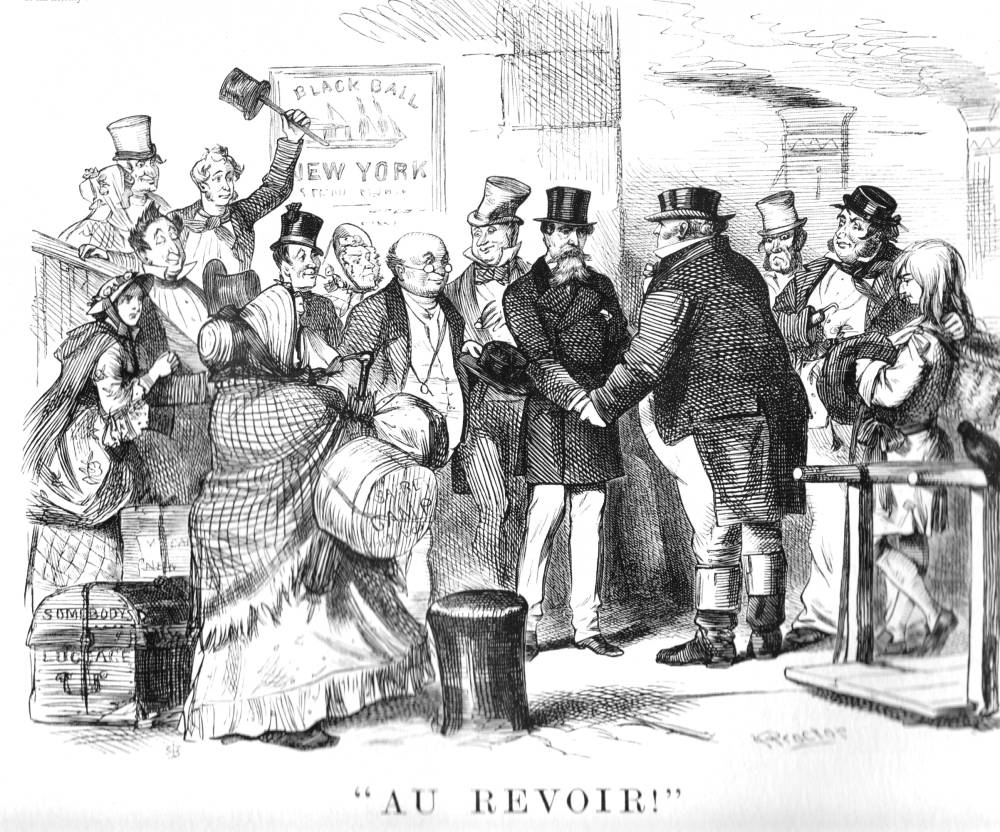

"Au Revoir!" (wishing Charles Dickens well on his impending journey to the United States.

Proctor was fortunate that the failure of the Empire coincided with the launch of what became the chief conservative rival to Punch: Judy, or the London Serio-Comic Journal, in May 1867. Initially illustrated by a cartoonist signing his name "ART," Judy soon recruited Matthew Somerville Morgan as chief cartoonist, but who left after a few months in order to concentrate on another weekly satirical journal The Tomahawk. Proctor succeeded him, but like Morgan, remained only a few months before moving on to yet another conservative-leaning weekly satirical journal, Will O' The Wisp, in 1868 (being replaced at Judy by William Henry Boucher).

His work for Will O' The Wisp saw Proctor achieve considerable fame, and he was celebrated in the press, particularly for his attacks on Gladstone. The cartoon Birds of Prey (19 December 1868, pp.170-171) was long remembered as one of the greatest such cartoons, imagining Gladstone as a vulture, about to tear apart the goddess Hibernia.

While Proctor then moved on from Will O' The Wisp quite quickly, he was sought-after as an illustrator, and was briefly considered by Charles Dodgson to contribute the illustrations to Through the Looking-Glass (while John Tenniel vacillated about returning for the sequel to Alice's Adventures in Wonderland). He also found plenty of illustration work for the children's weekly magazine, Our Young Folks' Weekly Budget, founded in 1871 by James Henderson. Henderson also launched Funny Folks, at which Proctor was employed as chief cartoonist from 1874. Proctor's chief contributions to Young Folks' were illustrations for Roland Quiz's series of "Tim Pippin" fantasy stories. He signed that work as "Puck," while reserving his surname for serious political cartoons in Funny Folks, and also employed the pen-name "P.O.P." for work on another boys' paper Sons of Britannia.

The signature used by Proctor for his serious, cartooning work.

By 1881, Proctor had shifted yet again, taking on the role of chief cartoonist at yet another new conservative magazine, Moonshine. Proctor's work not only appeared weekly in the magazine's pages, but also on large posters produced ahead of the 1885 General Election, depicting all the sorts of evils that would be the result of a Liberal victory.

At this stage of his career, Proctor finally seems to have settled down, and he remained at Moonshine for nine years (eventually succeeded by Alfred Bryan in 1889). His domestic life had also stabilised, with four of seven children surviving beyond infancy: John James (b.1862), Adam Edwin (b.1864), William Sawyer (b.1870), George Smith (b.1872), Annette Violet (b.1874), Robert Carlisle (b.1874) and Maryland (b.1879). Proctor may also have fathered an illegitimate child on a household servant, although the evidence for this is sketchy.

W. H. Bartlett's oil painting, Saturday Night at the Savage Club, 1890. Source: frontispiece to Watson (with a useful key). Proctor, left of centre, with his back to the viewer — in short beard and whiskers, thinning hair, wearing a greyish dinner jacket — leans forward over the table, reaching for a glass.

Proctor was a significant figure in social and clubland circles. A member of the Urban and Whitefriars' clubs (and a contributor to The Whitefriars' Chronicles), Proctor was also a stalwart of the Savage, and was prominent enough to appear in W. H. Bartlett's painting Saturday Night at the Savage Club, sitting alongside Sir Henry Irving, Sir Arthur Wing Pinero, G. A. Henty, Harry Furniss, and Luke Fildes. A popular after-dinner speaker and master of ceremonies, Proctor presided over events such as a reception for the Prince of Wales at the Inns of Court Rifle Volunteers and the Fly-Fishers' Club annual dinner. He also exhibited at the Royal Academy, and was elected to the Council of the City of London Society of Artists and the Guildhall Academy of Arts.

After a brief stint on the society paper The Sketch, Proctor's last major role was as chief cartoonist at Fun, which was struggling to regain respectability after its turn away from Gladstonian Liberalism and towards Liberal Unionism in 1893. Between 1894 and 1898, he excelled at attacking Gladstone and Rosebery, and then heaping praise on Salisbury's Unionist ministry from 1895. After the sudden death of Alfred Bryan in 1899, Proctor briefly returned to Moonshine, helping prop it up until the turn of the century, when he retired to the little hamlet of Brook, in Surrey.

Proctor contributed some valuable recollections to John Alexander Hammerton's Humorists of the Pencil (1905), in which the editor commented how greatly London clubland felt the departure of Proctor's wit and charm. During retirement, Proctor and his wife experienced the great shock of losing their eldest son, John James (d.1910), who was himself a cartoonist for The Globe, and their second son Adam Edwin (d.1913), who had made a career as a landscape painter and illustrator. It was to his eldest surviving son William Sawyer Proctor that Proctor bequeathed his small estate (£510 5s.), when he died on August 10, 1914.

Bibliography

Forbes, Frank. "Our Leading Cartoonists – IV. Mr John Proctor." The Temple Magazine, Vol. 3 (1898-1899): 467-471.

Hammerton, John Alexander. Humourists of the Pencil. London: Hurst & Blackett, 1905. 54-60.

Our Young Folks Weekly Budget. Christmas Number (19 December 1874): n.p.

Scully, Richard. Eminent Victorian Cartoonists – Volume II: The Rivals of "Mr Punch,". London: Political Cartoon Society, 2018 (esp. 52-92).

Watson, Aaron. The Savage Club: A Medley of History, Anecdote, and Reminiscence. London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1907.

Created 18 January 2022