The two illustrations here come from our own website. Click on them for more information and larger images. The second one can also be found in the book itself, and is discussed on pp.130-32.

In the twenty-first century it is rarely the case that imaginative literature is illustrated. There are exceptions, of course, notably in the form of special or limited editions; but illustration is usually considered to be the domain of children’s books, and, for many, is purely a matter of childhood and childishness. In the nineteenth century, by contrast, illustration was a central part of literary culture: what is the point, Carroll’s Alice speculates, of a book without pictures? In fact, most of the major novelists were illustrated, and every Victorian reader expected to engage with bimodal texts – texts in which the pictures ran in synergy with the words.

Many studies have examined this symbiosis in terms of how the illustrations interacted with the letterpress, but it is rarely the case that attention has been focused on the ways in which visual material influenced the wider process of reading. Did illustration make a difference to the perception of a text? Did it fundamentally change the generation of meaning as the reader/viewer was presented with what was sometimes a jostling competition between the pictures, those graphic marks on the page, and the abstract signs of printed letters?

These issues are explored in Julia Thomas’s ambitious and far-reaching study, The Victorian Mind’s Eye: Reading Literature in an Age of Illustration. In earlier publications Thomas has explored the relationships between nineteenth century illustration and its cultural settings, and here she offers a probing analysis of how the Victorians negotiated a bimodal text and the ‘physiological and psychological’ workings of this type of hybrid reading (16). Focusing on readers and the effects of intermediality, she offers an important new perspective that goes well beyond the usual investigations of illustrated material – which tend to focus on how an artist has interpreted written material – and resets the critical debate. In so doing, she draws extensively on understandings of the time and frames her arguments in contemporary criticism and philosophy.

In the Introduction Thomas outlines the ubiquity of illustrated material in an age when cheap paper and industrialized printing meant that it was relatively easy to produce a pictorial text, essentially creating a culture in which images and words were inextricably linked – a conjunction that stretches from the wood-engraved pages of Punch and The Illustrated London News to the illustrated serials of Dickens and Thackeray. This pairing of image and word meant that reading must involve ‘a constant movement and negotiation’ (8) between the two and, more importantly, demanded a ‘specific mode of reading’ (11-12) which, the author tells us, involves a fluid interaction between the ‘material and the immaterial’ eye (150). The images evoked in the reader’s mind by the written text’s descriptions are produced in competition with the ‘material’ images, and according to this line of reasoning demands a type of mental processing in which diverse material has to be synthesized.

The questions surrounding that nexus are taken up in Chapter One, and Thomas presents a detailed discussion of Victorian assessments of illustration and what it could, should, or might do, often relating them to contemporary understandings of the mind and the processing of information. This debate, Thomas demonstrates, had positive and negative implications. Illustration might be redundant, adding nothing to the reader’s imagination, and might interfere ‘with the intimate relation between author and reader’ (32), closing a text rather than opening it; and it might spoil the reader’s production of private images, suppressing the imagination and encouraging mental laziness. On the other hand, it could be purely positive, helping the reader/viewer to create those subjective impressions which grow out of, and are stimulated by, the marks on the page. As Thomas puts it, a design might unaccountably ‘generate [personal] mental images’ in the reader's ‘mind’s eye’ (31) with the creative power vested in the reader/viewer rather than the artist.

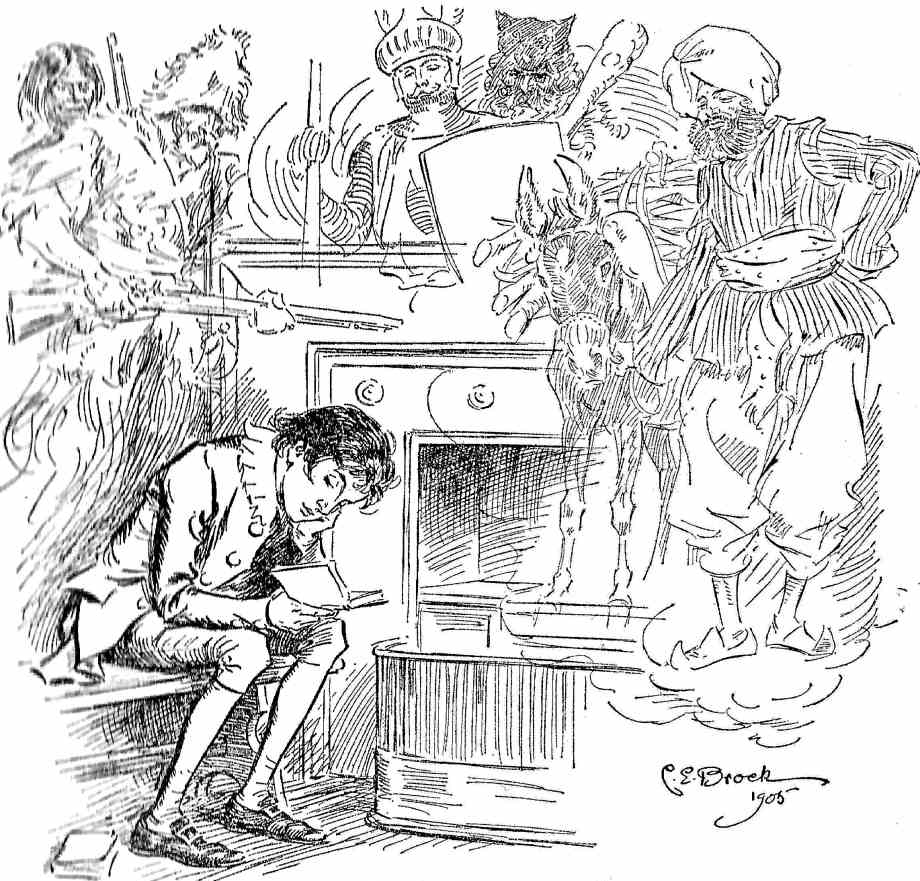

A Lonely Boy Was Reading (depicting the young Scrooge) by C.E. Brock (1905).

Those pros and cons are tested in chapters 2 and 3, and Thomas is careful, once again, to show that illustration might intensify or undermine the process of reading. On the plus side, she notes how the very provision of illustrations, especially those in colour, could make the engagement with the text more interesting and memorable by converting it into a ‘“Sensuous” form’ (101). The positioning of illustrations might also have a positive, generative effect, with images positioned before the relevant text being a means to amplify understandings of the letterpress. Illustration could add, the author contends, to a non-linear reading of a book – providing proleptic and analeptic information that extends the narrative out of its chronological frame (Chapter 2). In a certain way, Thomas suggests, pictorial material could act cinematically – flashing back and forward to offer all sorts of ‘entry points’ into the text while allowing the reader to construct a fluid mental conception of the writing (70). Yet a strong image or set of images could sabotage the whole thing, especially when there was a mismatch of the writer’s and artist’s conceptions, with the illustrator’s design stifling the reader’s subjective response.

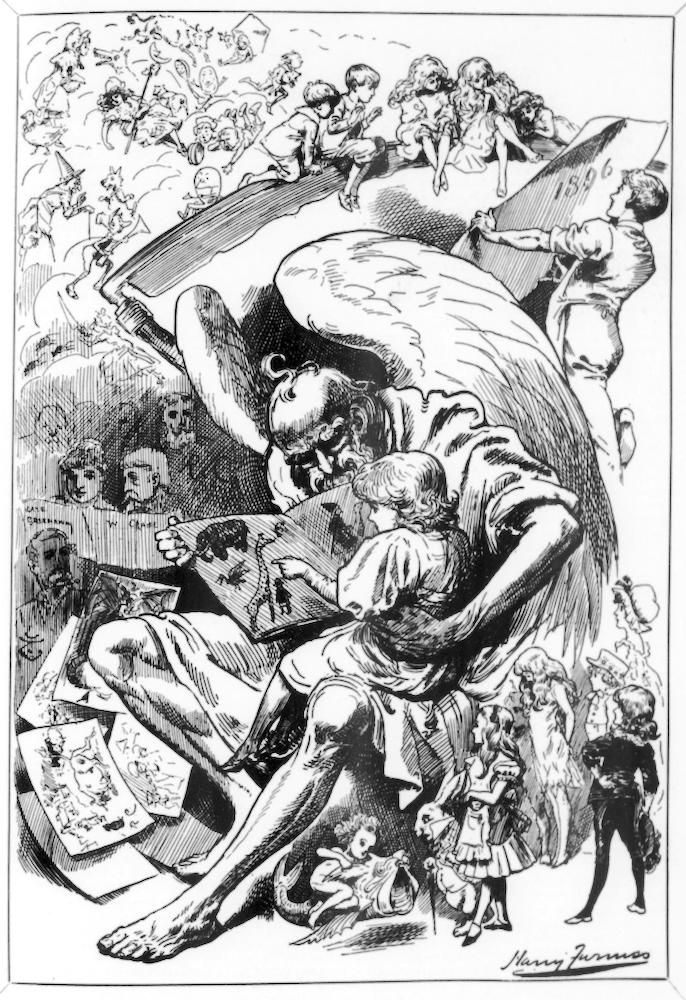

Illustrations and Illustrators by Harry Furniss (1896).

However, expansive effects were developed, Thomas argues, by the illustrations’ linkage to each other and to the outside world (Chapters 4 and 5). This ‘networked reading’ (Chapter 4, “The Networked Reading of Victorian Illustrations”), meant that the Victorians may have understood written texts in terms of the montage of accompanying designs, so producing a process of cross-referencing that reinforced impressions of a character or situation or theme. Further, an illustration might stimulate memory of an aspect of a text by linking to an external visual association; the illustrators made use of well-known pictorial tropes, and Thomas suggests that an illustration of a figure looking out of a window (a common device, especially in the book art of the 1860s) could amplify their reader’s notion of that event by linking to similar pictorial treatments of the same motifs and in the same manner. In short, interpictoriality added another layer of enrichment to understanding of the text, and at the very least ‘provided a way of securing the reader’s attention and promoting their interest’ in the writing (169).

But what happened to illustration – and why do we no longer expect to see it, or read our texts in the same way as the Victorians? In the conclusion, Thomas suggests that the partnership of words and images as practised in the nineteenth century has been replaced by the literariness of film – that most hybrid of forms – the partnering of text and illustration in comic books, and the multiple interactions of pictorial and written information in digital technology. In a certain way, the Victorians’ habit of visual reading has been passed down to modern generations, even if we no longer expect to see illustrations appearing in our books as a matter of course.

That possibility is well argued, and Thomas’s analysis as whole is persuasive. She writes with elegance and precision while animating her arguments with dry humour and a commonsense turn of phrase. Her use of contemporary sources is apposite and sometimes surprising, and the recovery of such material – much of it locked away in reviews and seemingly throw-away comments – is in itself a significant act of historical research and astute selection. All that I would have wanted in addition is more illustrations; the book only has 29 and would benefit from a more extended series.

Nevertheless, Thomas has provided a book which greatly expands the field of illustration studies. In shifting the emphasis from production to reception she shows how the graphic embellishment of written texts was central to the Victorians’ perception and interpretation of their vast literary canon, a part of the very fabric of reading which profoundly changed how texts were understood. That assertion has been a long time coming, submerged in diverse criticism, and Thomas brings it very much to the fore in this erudite and stimulating study. It will undoubtedly provide a conceptual framework for future studies in which the working of the Victorians’ seeing and reading will be traced in ever greater detail.

Bibliography

[Book under review] Thomas, Julia. The Victorian Mind’s Eye: Reading Literature in an Age of Illustration. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2025. pp. 224. ISBN: 9780198914600. £77

Created 13 April 2025