The following scan of a drawing which later appeared in Punch, and the Times article to which it refers, were both sent in by Shirley Nicholson. Commentary and formatting by Jacqueline Banerjee. The image may be used without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned them and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one. Click on the image to enlarge it, and on the thumbnail of Mulready's painting to find out more about it.

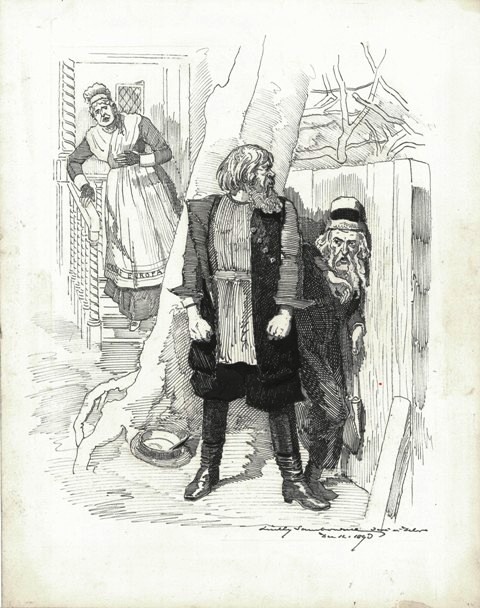

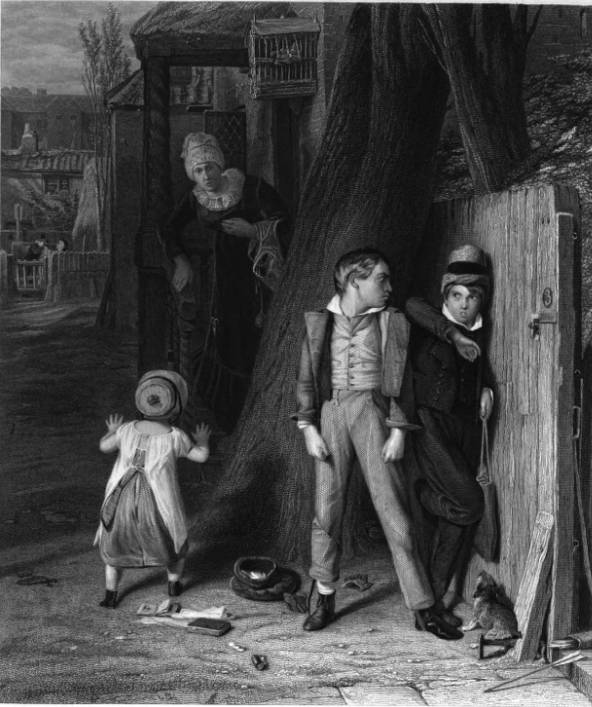

Left: A drawing (pen and ink) by Linley Sambourne (1844-1910) dated 12 December 1890 and published in Punch 20 December 1890: 290, captioned "The Russian Wolf and the Hebrew Lamb (after a well-known picture)." Right: William Mulready's painting, The Wolf and the Lamb, of c.1819-20. The latter elicited the following response from the Art-Journal, which featured it in 1856: "Mulready is the 'Æsop' of painters, inasmuch as beneath all his figurative expressions lies the moral of truth, fashioned indeed after the similitude of a fable, but cosily discerned and applied" (36). In Sambourne's iteration, a motherly figure, which we might now label "the West" looks aghast as she spots an elderly Jew shrinking from a dastardly Cossack. This follows the expression of righteous indignation by a large number of dignitaries at the cruelty of the Russians towards their Jewish population during the pogroms of the late nineteenth century.

Extracts from THE JEWS IN RUSSIA (The Times of 11 December 1890)

A meeting was held yesterday afternoon in the Guildhall to express public opinion upon the renewed persecutions to which millions of the Jewish race are subjected in Russia under the yoke of severe and exceptional edicts and disabilities. The meeting was called in pursuance of a requisition signed by the following:— The Archbishop of Canterbury, the Duke of Argyll, the Duke of Westminster, the Duke of Abercorn, the Duke of Newcastle, the Marquis of Ripon, the Marquis of Abergavenny, Earl Spencer, the Earl of Meath, the Baroness Burdett-Contts, Lord Tennyson, Lord Bramwell, Lord Rowton, Lord Brassey, Lord Addington, Mr. Stansfeld, M.P., [etc. etc. — of the many more listed, the most noteworthy perhaps are Cardinal Manning and Professor Huxley]

The LORD MAYOR, in opening the proceedings said,— In response to a very numerously signed requisition, I had no hesitation whatever in lending this great hall for the purpose of our gathering this afternoon. For centuries the citizens of London have been always ready to take a leading part in advancing the cause of religious and civil liberty. (Hear, hear.) But I venture to think that on no previous occasion has this noble hall been used for a more urgent purpose than that which hes called us together to-day,when we desire to show our sympathy and commiseration with the Jews in Russia who are now suffering under grievous and oppressive legislation. I earnestly hope that no word of a personal or hostile nature may be uttered at this meeting with reference to his Majesty the Czar. (Cheers.) As I imagine, the Czar of Russia is a good husband and a tender father, and I cannot but think that such a man must necessarily be kindly disposed to all his subjects. On his Majesty the Czar of Russia the hopes of the Russian Jews are at the present moment fixed. He can by one stroke of his pen annul those laws which now press so grievously upon them, and he can thus give happy life to those Jewish subjects of his who now can hardly be said to live at all. He has repeatedly and graciously intimated that the interests of his Jewish subjects are as near to his heart as the interests of the most Orthodox Russians. He cannot afford to have another class of serfs created in his kingdom, and the condition of the Jews in Russia is now rapidly approaching that of serfs; indeed, it may be said to be almost worse than that of the serfs, for they, at all events, had masters who were responsible for their wellbeing, whilst the Russian Jews are at the mercy of the Russian police. (Hear, hear.) Alexander II gained an imperishable crown by granting emancipation to the Russian serfs. Let Alexander III be encouraged to hand his name down to posterity as the emancipator of the Russian Jews. (Cheers.) Before I sit down I will read some extracts from letters I have received from distinguished men who are unfortunately unable to be present. The following telegram has been received from his Grace the Archbishop of Canterbury, whose absence is due to his recent domestic bereavement:—

trust that an influential resolution may convey to the Government of Russia the earnest prayer for immediate reconsideration of regulations which accumulate extreme distress upon its Jewish subjects." (Cheers.)

The following letter has been received from the BISHOP of LONDON:—

I have had some hope that, in spite of the pressure of other duties, I should nevertheless be able to attend the meeting on Wednesday and join my voice with those who will there plead for the suffering Jews in Russia: but I now find it impossible, and 1 can only write to say how warmly I sympathize wuith the purpose of the meeting and how earnestly I pray that its influence may have a great success....

[I]n expressing his regret that, owing to indisposition he is usable to be present, the DUKE of ARGYLL writes:—

There can be but one feeling among all parties and among all Churches in these islands against every form of persecution on account of religious belief. It is a barbarism unworthy of our age, and one that cannot be too loudly condemned by the voice of civilization. There is no pretence of disloyalty or of lawlessness against the Jews in any country in which they are dispersed, and any persecutor of them must be on account of religion alone or on account of the very excellency of their industry and thrift....

The EARL of MEATH then proposed the following resolution:—

That a suitable memorial be addressed to his Imperial Majesty the Emperor of all the Russias, respectfully praying his Majesty to repeal all the ex- ceptional and restrictive laws and disabilities which afilict his Jewish subjects: and beg his Majesty to confer upon them equal rights with those enjoyed by the rest of his Majesty’s subjects; and that the said memorial be signed by the Right Hon. the Lord Mayor, in the name of the citizens of London, and be transmitted by his lordship to his Majesty.

Verse Accompanying Sambourne's cartoon in Punch

Punch's written comment on the situation in Russia parodies a recent response to this meeting. Madame Olga Novikoff, a brilliant society figure and author who had won the praise of Gladstone, W. T. Stead and others, had written a letter to the Times decrying the British stance in general and the Guildhall gathering in particular:

I repeat that a great military Power, having at her disposal an army of two millions of well-disciplined and drilled soldiers, whom no European country dares to attack single-handed, can face calmly, and even good-humouredly, both the wild attacks of unscrupulous publicists, and mistaken protests of philanthropic meetings, though these be as imposing and brilliant as the Lord Mayor's Show itself."

The Punch writer then goes on to lampoon Madame Novikoff's own stance, using Portia's famous speech about mercy in The Merchant of Venice to do so:

The quality of mercy is o'erstrained,

It droppeth twaddle-like from Lord Mayor's lips

Upon a Russian ear: strength is twice scornful,

Scornful of him it smites, and him who prates

Of mercy for the smitten: force becomes

The thronéd monarch better than chopped logic;

His argument's — two millions of armed men,

Which strike with awe and with timidity

Prating philanthropy that pecks at kings.

But Mercy is beneath the Sceptre's care,

It is a bugbear to the hearts of Czars.

Force is the attribute of the "God of Battles";

And earthly power does then show likest heaven's

When Justice mocks at Mercy. Therefore, Jew,

Though mercy be thy prayer, consider this,

That in the course of mercy few of us,

Muscovite Czars, or she-diplomatists.

Should hold our places as imperious Slavs

Against humanitarian Englishmen,

And Jews gregarious. These do pray for Mercy,

Whose ancient Books instruct us all to render

Eye for eye justice! Most impertinent!

Romanist Marquis, Presbyterian Duke,

And Anglican Archbishop, mustered up

With Tabernacular Tubthumper, gowned Taffy,

And broad-burred Boanerges from the North,

Mingled with Pantheist bards, Agnostic Peers,

And lawyers latitudinarian, —

Lord Mayor's Show of Paul Pry pageantry,

All to play Mentor to the Muscovite!

Master of many millions! Oh, most monstrous!

Are we Turk dogs that they should do this thing?

In name of Mercy!!!

I have writ so much,

As ADLER says, with "dainty keen-edged dagger,"

To mitigate humanity's indignation.

With airy epigram, and show old friends,

GLADSTONE, and WESTMINSTER, MACCOLL and STEAD,

That OLGA NOVIKOFF is still O.K.

A Portia — à la Russe! Have I not proved it? [291]

The cartoon and poem together make a complex statement about the Russian treatment of Jews. Sambourne's depiction of western Europe as a sort of impotent nanny figure implies an element of mockery which supports Madame Novikoff's scoffing stance. Contemporary readers of the verse parody might also have been amused by its comical allusions to the dignitaries of Church and State, such as "Tabernacle Tubthumper" (Rev. Charles Haddon Spurgeon of the Metropolitan Tabernacle). Yet Sambourne's fundamental message, reinforced by reference to the Mulready painting, is abhorrence of bullying, that is, aggression towards the helpless. Madame Novikoff was much admired, but readers would have seen that both the Russian pogroms themselves, and her response to them, were very far from being "O.K." As for Madame Novikoff herself, in 1917 the editor of her memoirs would describe her as "everything from a Russian agent to a national danger, everything in short but the one thing she professed to be, a Russian woman anxious for her country's peace and progress" (6).

Links to Related Material

Bibliography

Editor's preface. Russian Memories, by Olga Novikoff ("O.K"). London: Howard Jenkins, 1917. 5-10. Project Gutenberg. Web. 15 January 2023.

Punch, or the London Charavari. Vol. 99 (20 December 1890). Project Gutenberg. Web. 15 January 2023.

Created 15 January 2023