Book illustration of the 1860s did not largely engage with politics, except when it appeared in the pages of Punch. The great majority of designs were published in literary and improving periodicals and gift-books, and commentaries on topical events were not acceptable within the context of this type of reading. Sandys was bound by this convention, and only made a ‘rare’ excursion ‘into contemporary politics’ (Schoenherr, p.19). Although he is principally an artist of neo-medieval or neo-classical fantasies, he presents two hard-hitting images which critique the mid-Victorian present: The Waiting Timeand The Old Chartist.

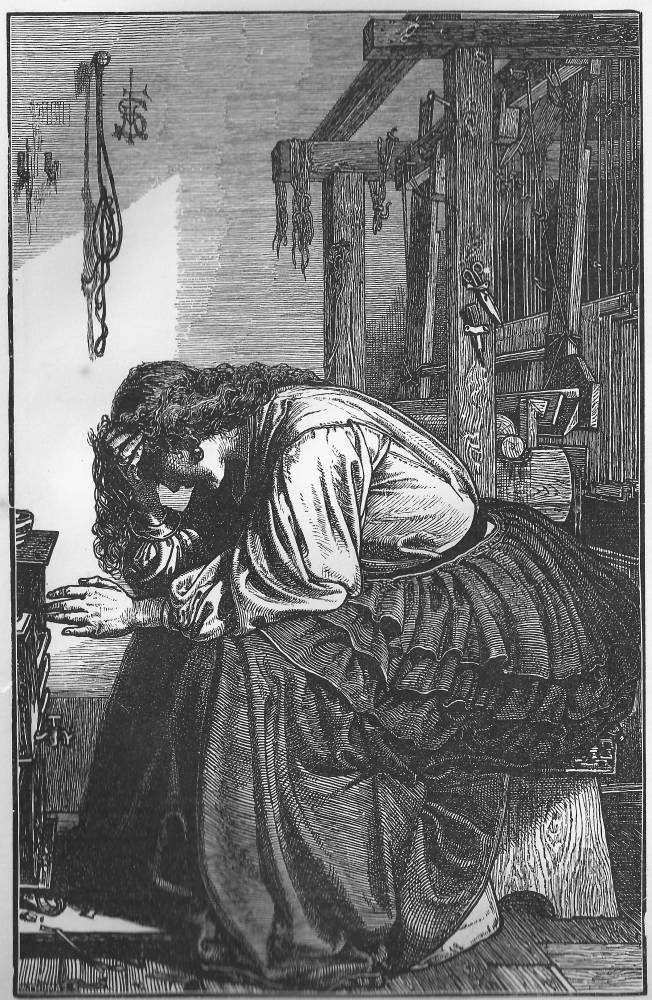

Left to right: (a) The Old Chartist. (b) The Waiting Time. [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

The Waiting Time accompanies ‘Waiting’, a pious verse by Sarah Doudney about the need for fortitude as we await God. But Sandys radically changes the focus. The weaver has no work because of the cotton embargo caused by the American Civil War, and in the absence of intervention by the British Government will probably starve, and her ‘waiting’ is simply waiting to die. Little of the immediate impact is conveyed in her monumental figure, but Sandys powerfully conveys her anguish in the form of her gestures, with one hand on her head and the other, a curiously distorted piece of drawing, stretching out hopelessly. Dramatic and unsettling, the image provides a direct comment on the brutality of lassez faire economics, and it is surprising to find in the pages of the conservative Churchman’s Magazine.

A different approach is adopted in The Old Chartist, which illustrates George Meredith’s verse. The contemplative figure has returned to his ‘dam’ England, following his transportation and imprisonment. The image is essentially a celebration of nostalgia. The intense detailing of plants and elements within the landscape depicts the character’s emotional attachment to the English scene, cataloguing each part of the natural world as he re-discovers them. The political message of the illustration – which is not quite that of the poem – is one which points to the brutality of the punishment, separating from country a man who is obviously a patriot.

Both images provide a note of contemporaneity that complements the artist’s escapism. It is at the same time another aspect of his use of Pre-Raphaelitism, presenting an archaic art which, as in the work of Millais and Holman Hunt, is nevertheless very much of the present.

Last modified 15 July 2013