Age 19. From a photo by the London Stereoscopic Co.

(Portraits of Celebrities, 395).

Frederic Villiers rose from modest beginnings in Clerkenwell to become "[o]ne of the pre-eminent war artist-correspondents of the Victorian era" (Roth 377). In genealogy records, his name is spelled Frederick, and that of his father, a "licensed victualler" ("Villiers, Frederic 1851-1922"), was originally Henry Richard Levy. This suggests Jewish origins on his paternal side, although his mother's maiden name was Caroline Bradley, and has a different resonance.

Born on 23 April 1851, young Villiers soon discovered an aptitude for sketching. The story goes that "when convalescing from measles he would draw regiments of soldiers with fixed bayonets on his school slate" (see Bullard 156-57). This made his doctor imagine a military future for him, which he would indeed have, but in rather an unusual way. According to his obituary in the Publisher's Weekly, the boy was educated in Guines, pas-de-Calais, in France, before studying art at the British Museum (presumably by copying artefacts) and the South Kensington Schools, and entering the Royal Academy Schools in 1871.

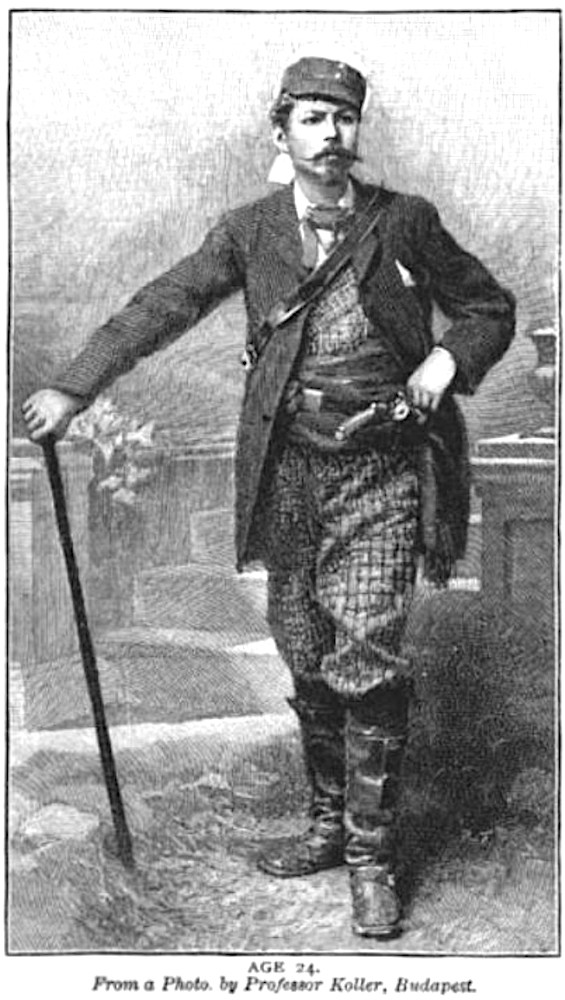

Age 24. From a photo by Professor Koller, Budapest

(Portraits of Celebrities, 395).

Villiers did show some paintings at the Royal Academy and the Royal Institute of Oil Pinters, and tried for a while to establish a career at the easel. His first application to the Graphic was turned down, but he was accepted later, when he offered to go and cover the Serbian War for the journal. On this mission he was teamed with the already well-seasoned Scottish war correspondent Archibald Forbes (1838-1900). His future was set. From this beginning Villiers went on to cover the Russo-Turkish War, and many more conflicts, including the Afghan War, conflicts in Egypt in the early 1880s, Serbia's invasion of Bulgaria in 1886, and then the conflict in Burma. This was an entirely different kind of artist's life: far from being finished works, his on-the-spot sketches in war zones, often made on a tiny notepad, were necessarily rough-and-ready. Several sketches by Villiers reproduced in Pat Hodgson's book about war illustrators are described as "redrawn," and indeed in one place Hodgson writes that his work was "always redrawn by a staff artist" (146; emphasis added).

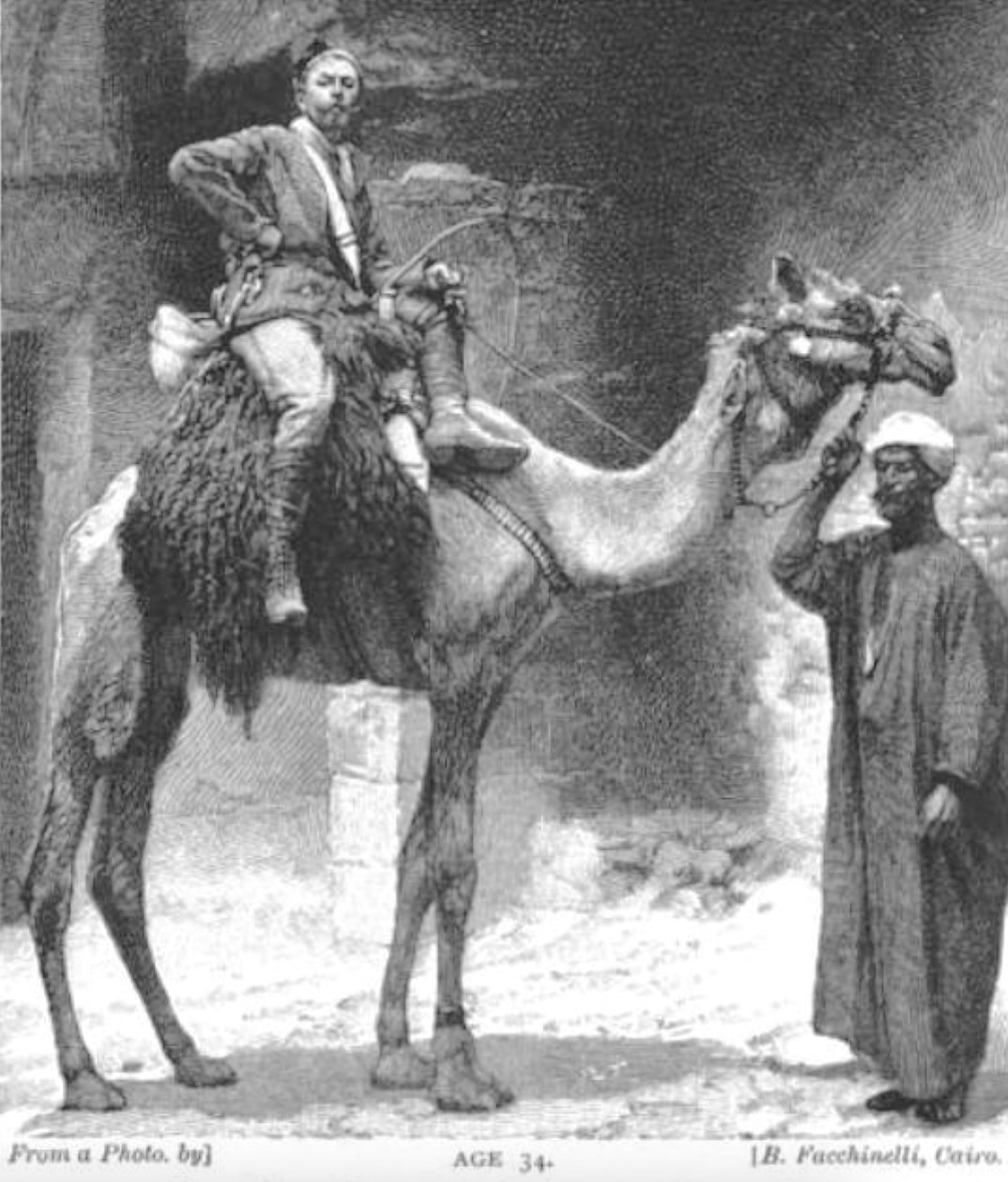

All the same, it vividly conveyed events on the battlefield, and Villiers became well-known. His fame spread further when he made lecture tours in America and Canada during the lull that followed. Then in 1894 he was back in the battlefield, this time bearing witness to the Japanese invasion of Korea. On the occasion of meeting the Emperor of Korea we see him surreptitiously making "a few notes on the scene on my shirt cuff" (Villiers, His Five Decades II:248). In like manner, taking every opportunity to capture scenes as they unfolded, he also covered the Thirty Days War between Greece and Turkey in 1897, conflict in the Sudan, and the Boer War, providing visual records and press reports on as many as "twelve major conflicts as well as many lesser ones" (Roth 377 and 378).

Age 34. From a photo by B. Fachinelli, Cairo.

(Portraits of Celebrities, 395).

When introducing his sketches, Philip Gibbs sees Villiers as representing the "greatest of the Old Guard" of war reporters (v). In some specific ways too he was a pioneer — the first war reporter to get around by bicycle, and to use a cine camera. This began while he was while reporting on the Thirty Days War:

Luckily I was well housed during the fighting in front of Volo, for the British consul insisted on my residing at the consulate. To me it was campaigning in luxury. From the balcony of the residence I could always see of a morning when the Turks opened fire up on Velestino Plateau; then I would drive with my cinema outfit to the battlefield, taking my bicycle with me in the carriage. After I had secured a few reels of movies, if the Turks pressed too hard on our lines I would throw my camera into the vehicle and send it out of action, and at nightfall, after the fight, I would trundle back down the hill to dinner. [Villiers, Five Decades II: 170]

Villiers' own words give an idea of the esteem in which he was held by the authorities (in this case, the British consul), the risks he took, and his rather swashbuckling brand of insouciance. By the end of the Victorian period war reporting had simply become a normal way of life to him.

"Present Day" (i.e., 1894) Age 24. From a photo by Dickinsons,

New Bond Street (Portraits of Celebrities, 395).

Remarkably, considering the dangerous situations in which he often found himself, Villiers' story continued long after the end of the Victorian era, up to and right through the Great War itself. The American trade journal, Publishers' Weekly, rounded up these later exploits usefully in its obituary of him: he was "with the Japanese against the Russians in 1904, with the Spanish expeditionary force in Morocco in 1909, with the Italians in Tripoli in 1911, and went thru the two Balkan wars of 1912 and 1913. He saw all the battles of note in the World War, going thru the campaigns in France from 1914 to 1918" (1120). His work appeared not only in the Graphic, but also in the Illustrated London News, and a range of other publications. Contributing to his increasingly legendary status, he wrote about his experiences at length in several books, notably his two-volume Villiers: His Five Decades of Adventure (1920). He was often photographed, whenever possible sporting his decorations and medals.

Such an adventure-seeker would seem to have had little time for family life, but genealogical research reveals that Villiers did get married, if a little later than most, at the age of 47. Frederic and his wife Louisa had one daughter, Mary Carolyne Dorothea, born in Hampstead in 1900. When he died after a prolonged illness on 5 April 1922, just short of his 71st birthday, he was still admired enough for his death to be immediately and widely reported both at home and abroad: obituaries appeared in many major newspapers, including the New York Times, where the very next day's issue ran the news under this dramatic headline: "VILLIERS IS DEAD; WRITER OF WAR; Was Famous for Sketches and Dispatches in Twentyone Campaigns. MODEL FOR KIPLING'S HERO. Original of Dick Heldar [in The Light that Failed, 1891]. It was a fitting send-off.

Bibliography

Blathwayt, Raymond. Interviews. London: A.W. Hall, 1893. Internet Archive, from a copy once held by Highgate Library in N. London. Web. 10 April 2025.

FreeBMD (transcription of the Civil Registration index of births, marriages and deaths for England and Wales).

Gibbs, Philip. "A Salute to Frederic Villiers." In Frederic Villiers' Days of Glory: The Sketchbook of a Veteran Correspondent at the Front (see below).

Hodgson, Pat. The War Illustrators. New York: Macmillan, 1977. See especially pp. 24-25.

"Obituary Notes: Frederic Villiers" The Publishers' Weekly Vol. CI (15 April 1922): 1120. Internet Archive. Web. 10 April 2025.

"Portraits of Celebrities: Frederic Villiers." Strand Magazine, Vol. 8 (July-December 1894): 395. Google Books. Free ebook. Web. 10 April 2025.

Roth, Mitchel P. The Encyclopedia of War Journalism 1807-2015. 3rd ed. Amenia, NY: Grey House Publishing, 2015. Entry: pp. 377-78.

Villiers, Frederic. Days of Glory: the sketch book of a veteran correspondent at the front. New York: George H. Doran, 1920. v-x. Internet Archive, from a copy in the State Library of Pennsylvania. Web. 10 April 2025.

_____. Villiers: His Five Decades of Adventure. Vol. 1. New York and London: Harper, 1920. Internet Archive, from a copy in the University of California Libraries. Web. 10 April 2025.

_____. Villiers: His Five Decades of Adventure. Vol. 2. New York and London: Harper, 1920. Internet Archive, from a copy in the University of California Libraries. Web. 10 April 2025.

"VILLIERS IS DEAD." New York Times (6 April 1922), p. 14.

Created 10 April 2025