Images scanned by the author. Click on them to enlarge them and for more information, including their terms of reuse.

Figures 1 through 4. Left: Phiz's thirteenth monthly illustration for the serialisation: Major Bagstock is delighted to have that opportunity (April 1847). Left of centre: Phiz's nineteenth monthly illustration for the serialisation: "Joe B. is sly, Sir, devilish sly!" (June 1847). Right of centre: Harry Furniss's Charles Dickens Library Edition of the Major, with the Native hovering constant attendance in the background: "Joey B." (1910). Right: Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s study of the Major and his much chivvied valet wearing African ear-rings: Major Bagstock and the Native (1867).

Dickens can be ambivalent, or worse, about matters of race and Empire. In Bleak House (1853), for instance, he criticises Mrs. Jellyby's misguided philanthropy, and debunks Rousseau's idea of the noble savage: the project for an agricultural colony on the shores of the Niger goes awry when a local chieftain sells the volunteers into slavery in order to purchase rum. Later, in The Perils of Certain English Prisoners in Household Words, written in response to the 1857 Sepoy Mutiny, his characterization of the "native" George Christian King who aids the pirates is vituperative and unquestionably racist. But the mute, unnamed Native in Dombey and Son (serialised 1846-48), Major Bagstock's vilified and oppressed valet, stands in sharp contrast to these characters, and is shown in a much more positive light.

Throughout the novel, Dickens raises questions about race and privilege that are as valid today as they were when he first raised them. Despite the focus suggested by the title, he often deals with the dispossessed, the undervalued, the economically and socially underprivileged whose worth male-dominated, upper-middle-class society generally fails to acknowledge. Such characters include Florence Dombey, the daughter whom Dombey undervalues because, as a mere female, she cannot grow up to run the family business; Walter Gay, the young junior clerk conveniently transferred overseas by his vindictive supervisor, Carker; Rob the Grinder, the charity boy who learns that the only way to advance himself is to curry favour with one's superiors; and, most strikingly of all, Major Bagstock's much put-upon servant. These undervalued characters, Dickens implies, matter as much or more in the great scheme of things than the exploiters, manipulators, and social sycophants who all too often constitute "respectable society." And, lest Dickens's irony is lost on present-day readers, the "Native" is the only character in the novel not native to Great Britain: he remains throughout a voiceless, nameless immigrant and outsider.

He is, however, shown far more positively than his master, the egotistical Major, to whose abusive and despotic treatment the transported African submits rather than resists. In essence, Dickens reverses the roles of the civilised and uncivilised in this novel, as the racial other displays Christian tolerance while his white employer is a brutish slave-driver. Dickens critiques the absolute master-servant relationship embodied in the Major's treatment of the Native. This, he suggests, derives from middle- and upper-class Victorians' desires for possession and power. They considered the nonwhites to be commodities without any characteristics, and possessed them for servants to flaunt the wealth and power of the empire and to steep themselves in self-satisfaction. Their names and nationalities do not deserve even the slightest notice, as is evident from Miss Tox's ignorance: "Miss Tox was quite content to classify [the Major's dark servant] as a 'native'" (Tanaka 950). He emphatically treats Bagstock as an object of Juvenalian satire and directs readers' sympathies to the much-maligned and mistreated Native. This long-suffering character reveals that Dickens was not consistently negative about the racial other.

Somewhere between the Dark Continent and the White Cliffs of Dover, the young man with the dark skin whom Bagstock regularly vilifies, castigates, and terrifies has lost his name. Dickens's illustrators are left to suggest his appearance. All we see of his skin in the original Phiz illustrations as the Native ministers to his imperious master's needs and dodges his blows is his physiognomy; the rest of him is enveloped and presented to English society in the gorgeous packaging of a liveried servant. The Native's only sources of identity are his subservient function and his skin — and, according to later illustrator Harry Furniss, his decidedly unEuropean hair.

Figure 3 (detail): Furniss's only illustration of the Native shows him hovering above the Major, ready to serve him a beverage (1910).

Even though he is a secondary character, Dickens uses the Native from an unspecified African country as a comic foil to the self-important Major Bagstock. The Native is "an indigenous inhabitant from abroad" whom Bagstock has trained as a domestic servant and imported from an unspecified British colony. In Chapter 20, the narrator mentions that the servant is rumoured to be the leader of a vanquished African nation: he is an "unfortunate foreigner (currently believed to be a prince in his own country)" (334), although this identification is at best tentative. Unlike all the other principal and secondary characters in the novel, the Native wears an elaborate but ill-fitting uniform, and has no proper name, but answers to any "vituperative epithet" that that the imperious retired army Colonel may choose to hurl at him. Thus, illustrators such as Phiz (1853), Sol Eytinge, Jr. (1867), Fred Barnard (1873), and Harry Furniss (1910) show an elaborately uniformed person of colour who seems terrified of his employer, and is often reduced to a state of comedic confusion.

Dickens's construction of the character of the Native chapter by chapter

In Chapter 7, "A Bird’s-eye Glimpse of Miss Tox’s Dwelling-place: also of the State of Miss Tox’s Affections," Dickens establishes the relationship between Lucretia Tox and her retired tenant, Major Joseph Bagstock, just returned from his final overseas posting accompanied by a non-European servant:

At this other private house in Princess’s Place, tenanted by a retired butler who had married a housekeeper, apartments were let Furnished, to a single gentleman: to wit, a wooden-featured, blue-faced Major, with his eyes starting out of his head, in whom Miss Tox recognised, as she herself expressed it, "something so truly military;" and between whom and herself, an occasional interchange of newspapers and pamphlets, and such Platonic dalliance, was effected through the medium of a dark servant of the Major’s who Miss Tox was quite content to classify as a "native," without connecting him with any geographical idea whatever. [Chapter VII, "A Bird’s-eye Glimpse of Miss Tox’s Dwelling-place: also of the State of Miss Tox’s Affections," Vol. I: 101-102]

From the seventh chapter through the fifty-eighth, Dickens develops the character whom Miss Tox dubs "the native" through his relationship with his employer (or perhaps "colonial task-master" would be more accurate) and through three monthly illustrations by Hablot Knight Browne. The Major never addresses his dark-skinned servant by name, but merely by "any vituperative epithet" that serves to denigrate the valet such as "scoundrel," and the subservient character never actually speaks to the Major or anyone else throughout the reported conversations in the novel. Colonialism as epitomized by the dictatorial Bagstock has, as it were, deprived the servant of speech and individual identity as he simply exists to satisfy the Major's needs, carrying his parcels, tidying his rooms, pouring his wine, and, above all, modelling a stylish if not somewhat ostentatious servant's livery. Miss Tox interacts with the servant in an utterly aloof manner as he acts as Bagstock's postman: "an occasional interchange of newspapers and pamphlets, and such Platonic dalliance, was effected through the medium of a dark servant of the Major's, whom Miss Tox was quite content to classify as a "native," without connecting him with any geographical idea whatever" (Ch. 7, Vol. I: 102).

In Chapter 20, Bagstock advances his plan to become the boon companion and confidant of the lonely, alienated, but decidedly rich widower Paul Dombey, Sr. He sees himself as a facilitator of Dombey's entry into London society, and possibly even of his new friend's second marriage. The incident which will initiate this intimate relationship is to be a trip out of town, preceded by a sumptuous bachelor breakfast in Major's apartments. Although the Major has made extensive arrangements, the faithful but somewhat bumbling gentleman's gentleman fails to produce the collation as Dombey arrives:

"Where is my scoundrel?" said the Major, looking wrathfully round the room.

The Native, who had no particular name, but answered to any vituperative epithet, presented himself instantly at the door and ventured to come no nearer.

"You villain!" said the choleric Major, "where’s the breakfast?"

The dark servant disappeared in search of it, and was quickly heard reascending the stairs in such a tremulous state, that the plates and dishes on the tray he carried, trembling sympathetically as he came, rattled again, all the way up.

"Dombey," said the Major, glancing at the Native as he arranged the table, and encouraging him with an awful shake of his fist when he upset a spoon, "here is a devilled grill, a savoury pie, a dish of kidneys, and so forth. Pray sit down. Old Joe can give you nothing but camp fare, you see." [Chapter 20, "Mr. Dombey goes upon a Journey," Vol. I: 329]

Figure 5: Phiz's twenty-first monthly illustration for the serialisation: The eyes of Mrs. Chick are opened to Lucretia Tox (July 1847).

Dickens finds the hapless servant indispensable in revealing the Major's mean-spirited nature and in affording a degree of physical comedy, at the expense, of course, of the Native, who, despite his best efforts, never seems to be able to satisfy his demanding colonial master. In a later scene, Dickens uses the servant as an object of romantic farce, as the novelist exposes the old maid, Miss Tox, to her friend Mrs. Chick's censure in having the temerity to set her cap at Paul Dombey, Sir., Mrs. Chick's own brother. Formerly the ladies have been best of friends, but now, as Dickens proclaims through the chapter title and Phiz's farcical illustration for Chapter 29, Mrs. Chick's eyes are suddenly open to Lucretia Tox's motivation:

The room door opening at this crisis of Miss Tox’s feelings, she started, laughed aloud, and fell into the arms of the person entering; happily insensible alike of Mrs. Chick’s indignant countenance and of the Major at his window over the way, who had his double-barrelled eye-glass in full action, and whose face and figure were dilated with Mephistophelean joy.

Not so the expatriated Native, amazed supporter of Miss Tox’s swooning form, who, coming straight upstairs, with a polite inquiry touching Miss Tox’s health (in exact pursuance of the Major’s malicious instructions), had accidentally arrived in the very nick of time to catch the delicate burden in his arms, and to receive the contents of the little watering-pot in his shoe; both of which circumstances, coupled with his consciousness of being closely watched by the wrathful Major, who had threatened the usual penalty in regard of every bone in his skin in case of any failure, combined to render him a moving spectacle of mental and bodily distress.

For some moments, this afflicted foreigner remained clasping Miss Tox to his heart, with an energy of action in remarkable opposition to his disconcerted face, while that poor lady trickled slowly down upon him the very last sprinklings of the little watering-pot, as if he were a delicate exotic (which indeed he was), and might be almost expected to blow while the gentle rain descended. Mrs. Chick, at length recovering sufficient presence of mind to interpose, commanded him to drop Miss Tox upon the sofa and withdraw; and the exile promptly obeying, she applied herself to promote Miss Tox’s recovery. [Chapter 29, "The Opening of the Eyes of Mrs. Chick," Vol. I: 496-97]

Miss Tox had intended to fall into the arms of the monocled Major, who would prove a suitable consolation prize since Mrs. Granger has bagged Dombey. And watching and absorbing all this social manipulation and domestic intrigue is the young Black foreigner in splendid servant's livery. By virtue of his position as Bagstock's factotum, the Native must wear European clothes and respond to commands given in English. Nobody ever addresses him by his actual name, and he apparently feels incapable of speaking English; the sole vestige of his former identity and his "native" social status are his oversized ear-rings, particularly evident in the image of him provided by American illustrator Sol Eytinge, Junior, for the Diamond Edition of the novel, issued just after the American Civil War. Undoubtedly American readers in 1867 would have identified the Native as what they would have termed a "house slave," as opposed to a Southern's estate's field slave: a discreet, uniformed lackey expected to perform all manner of domestic tasks. And, as Tanaka observes, the badge of his servitude, his extravagantly braided uniform is ill-fitting:

But however elaborately his outward appearance may be Europeanized, his essential differences remain conspicuous. The incongruousness of his clothes is too clear: " ... the Native ... on whom his European clothes sat with an outlandish impossibility of adjustment - being, of their own accord, and without any reference to the tailor's art, long where they ought to be short, short where they ought to belong, tight where they ought to be loose, and loose where they ought to be tight - ... " (278-79). His grotesque appearance is an inevitable consequence of mimicry. Mimicry at once increases his comicality and menaces society silently. We might then wonder at a "pair of ear-rings" (278), probably a folk ornament, in his dark brown ears. Are they worn as a sign of resistance to an image of pseudo-white man? [Tanaka 963]

Other characters, Good Mrs. Browne and Rob the Grinder, also demonstrate that names may be false flags in this novel. Since Rob Toodle, the charity boy, is anything but a "grinder" or diligent student, his heroic epithet "The Grinder" is as misleading as "The Native" (denoting a foreigner, not a person born in the British Isles), and "Good Mrs." is equally spurious since Alice Marwood's mother was never married. Moreover, as her theft of Florence's clothing demonstrates, she is the modern-day, urban equivalent of the traditional witch of such cautionary fairy-tales as "Hansel and Gretel."

The Choleric Major, "an over-fed Mephistopheles," and his much berated Man Friday

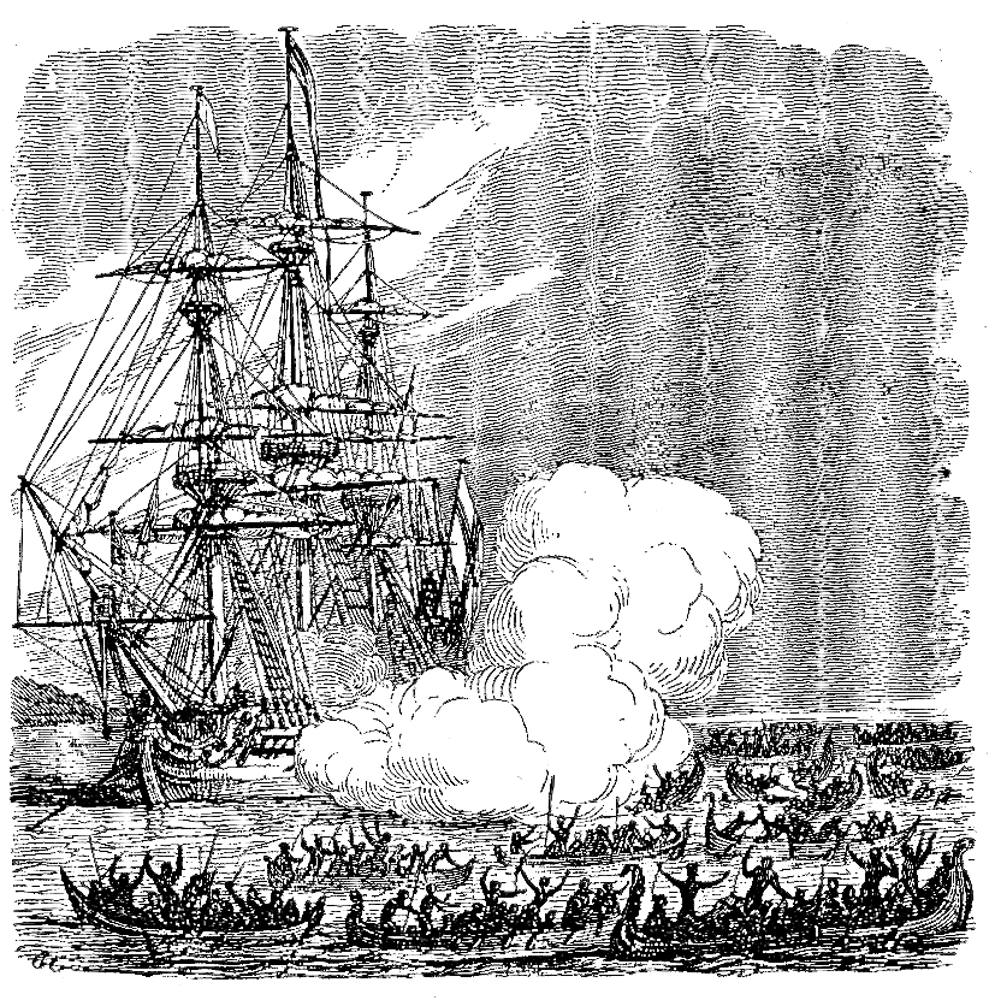

Figure 6: George Cruikshank's 1831 wood-engraving depicts the death of Friday as seen from a distance, depersonalizing the event, as if his demise is merely collateral damage in the naval engagement in Islanders attack Crusoe's ship, killing Friday (1831).

The former colonial administrator, home after decades of diligent service, brings with him a vestige of his colonial authority and imperium. In this respect, Dickens renders Major Bagstock a parody of one of his favourite childhood heroes, Daniel Defoe's Robinson Crusoe. However, Bagstock is no evangelical Crusoe, who bears the White Man's burden with Christian benevolence and sympathy as he educates and refines the former cannibal into a civilised and enlightened being. But Crusoe at least gives his servant a voice. Friday (obviously not his actual name, but a European identity conferred upon him) remains faithful to his white-skinned master until he dies in service, riddled through by native arrows as he mocks the ship's attackers in the second book of Robinson Crusoe (1719), illustrated for nineteenth-century readers by George Cruikshank in John Major's 1831 edition as The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe. Friday dies apparently trying to curry favour with his European shipmates by ridiculing the native force that has surrounded the vessel. But Dickens reverses the stereotypical natures of the European master and colonial slave by making the Native a model of Christian tolerance and forebearance, and the sputtering, posturing Major a vindictive brute, a very devil, although owing to apoplexy his skin colouration is blue rather than black.

Dickens wrote to his illustrator, "Phiz," that he wanted Major Bagstock to be "a kind of comic Mephistophelean power in the book" the Devil’s minion who comes down to earth to help Faustus seal his pact with the Devil (Major Bagstock keeps reminding us how he is "devil-ish sly""). Indeed, despite his light skin and rotundity, Bagstock is the very Devil of a schemer and manipulator who makes things happen in the Dombey plot:

The Major makes Dombey’s second marriage to Edith Granger happen; he introduces the two of them in Leamington Spa. Bagstock is the comic foil to Mr. Dombey, much as Sam Weller is the comic foil or sidekick to Mr. Pickwick in Dickens’s first novel. Where Dombey is dull, straight-laced, and impossibly prim (the chapters involving him, and his alienated daughter Florence, are the dullest in what is otherwise a very colourful novel), the Major is loud, obnoxious, and endlessly entertaining: in appearance, in speech, in action.

. . . the Native’s lack of any name seems an even greater anomaly. What’s more, the Major never uses one word when he can use ten, whereas we never hear the Native speak. It’s almost as if the English language itself is the dominion of the conqueror, and the conquered, or colonised, is not even permitted to use it. [Oliver Tearle]

In the programs of illustration previous to W. H. C. Groome's (1900), the Native is patently an African; however, in the turn-of-the-century Collins Clear-type Pocket edition, Groome has transformed him into an East Indian servant with a gorgeous silk uniform and oriental slippers suggestive of The Raj, rather than of an English valet in regular livery.

Major Bagstock, standard bearer and beneficiary of Empire, has his unnamed native servant kitted out in the fashionable style of a gentleman's gentleman, in a tailcoat with epaulettes. But Groome reminds readers of the Native's colonial origins with his silk trousers and turban, a sure indication of his South Asian origins, although the text implies (based on the far-flung corners of Empire where his employer has served) that he is an African, and, indeed, perhaps a former African prince.

Figure 7: W. H. C. Groome's concluding illustration is much more critical of the Major's brutal treatment of his colonial servant and much less sympathetic to his employer, The unfortunate Native suffered terribly (1900).

At his last appearance Dickens's narrator has conferred a name of sorts upon Major Bagstock's Man Friday: The Native. Having had his financial and social prospects dashed by the dual collapses of Dombey's second marriage and commercial empire, the egocentric major retreats to his club and his rented rooms. Nursing a grievance against the universe and unable to deal with his feelings of frustration and loss in a more rational and pacific manner, he vents his indignation and disappointment upon his hapless servant. Dickens's description of his violent and irascible behaviour includes a military term suggestive of quelling a native revolt with military technology: "fusilladed" and "riddled through and through" (Ch. 58, Vol. II: 452), as if with rifle bullets directed at him by British infantry on some distant colonial battlefield.

That he was a suspicious, crabbed, cranky, used-up, J. B. infidel, Sir; and that if it were consistent with the dignity of a rough and tough old Major, of the old school, who had had the honour of being personally known to, and commended by, their late Royal Highnesses the Dukes of Kent and York, to retire to a tub and live in it, by Gad! Sir, he’d have a tub in Pall Mall to-morrow, to show his contempt for mankind!

Of all this, and many variations of the same tune, the Major would deliver himself with so many apoplectic symptoms, such rollings of his head, and such violent growls of ill usage and resentment, that the younger members of the club surmised he had invested money in his friend Dombey’s House, and lost it; though the older soldiers and deeper dogs, who knew Joe better, wouldn’t hear of such a thing. The unfortunate Native, expressing no opinion, suffered dreadfully; not merely in his moral feelings, which were regularly fusilladed [emphasis added] by the Major every hour in the day, and riddled through and through, but in his sensitiveness to bodily knocks and bumps, which was kept continually on the stretch. For six entire weeks after the bankruptcy, this miserable foreigner lived in a rainy season of boot-jacks and brushes. [Chapter 58, "After a Lapse," Vol. II: 452]

Dickens's implication that the Major resorts to violence as a way of assuaging his frustration at Dombey's fall may have prompted W. H. C. Groome to transform the dark-skinned general factotum from an African originating in no particular region of the Dark Continent to an East Indian houseboy, gorgeously attired and utterly undeserving of the Major's ill-treatment. The scene in question may be an oblique allusion to the British army's putting down the 1857 Sepoy Mutiny in India. Even though Dombey and Son was published in the decade previous to the Indian mutiny, readers in the early twentieth century might well have overlooked the initial publication circumstances to focus upon the exploited and much-abused East Indian and British treatment of the revolting Sepoys fifty years earlier.

Even though the Native is a secondary and essentially one-dimensional character, Dickens effectively deploys him as a comic foil to the self-important, blustering Major. The Native, Bagstock's valet(indeed, as far as the text reveals, his only servant), is presumably a "native" whom Bagstock has trained as a domestic servant and imported from an unspecified British colony. Unlike most of the characters whom Groome and the other illustrators have portrayed, the Indian-attired valet answers to any "vituperative epithet" that the imperious Major may choose to hurl at him. Groome departs from the precedents of Phiz and Barnard by depicting the Major's servant in eastern slippers, short trousers, silken vest, and turban.

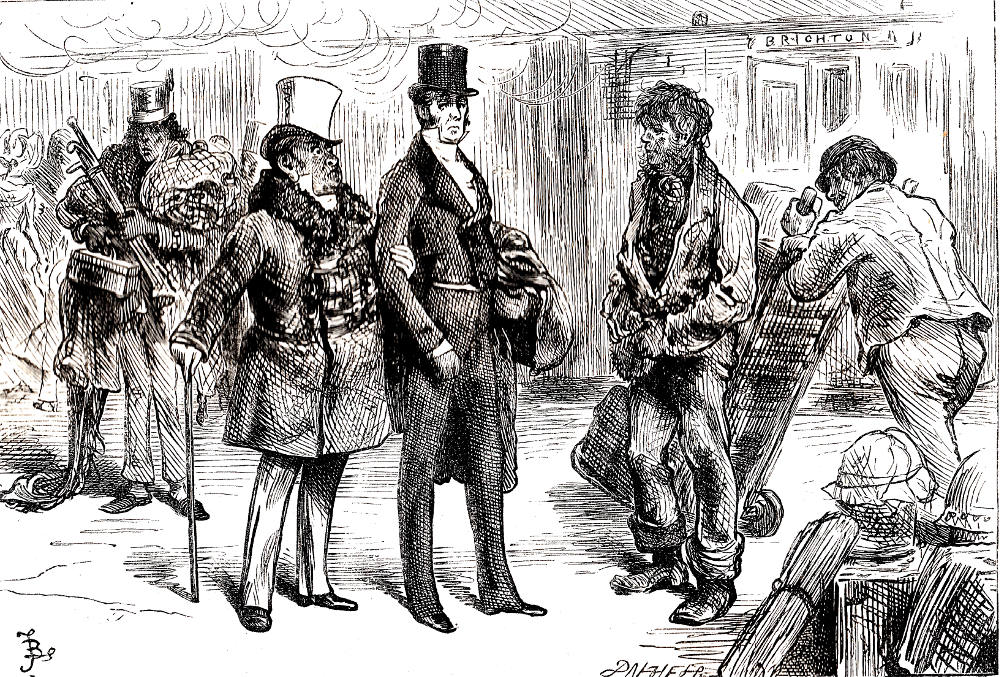

Although he is the chief figure in Dickens's colonial discourse in the novel, and although the Native figures prominently in several of Phiz's original serial illustrations, it is easy to lose sight of him in the later programs of illustration for Dombey and Son, particularly in Kyd's Characters from Dickens in the popular Player's Cigarette Card series, and in the composite woodblock engravings by Fred Barnard and Dalziels for the 1873 Household Edition volume.

Figures 8 and 9. Left: Fred Barnard's introduction of the scarlet Major: "Take advice from plain old Joe, and never educate that sort of people, sir." (1877). Right: Clayton J. Clarke's Player's Cigarette Card No. 7 watercolour study: Major Bagstock (1910).

The Imperial Context: A Post-colonial Footnote

In such 1840s novels as Dombey and Son and Barnaby Rudge Great Britain's empire serves as a test of manhood for the hero. As is the case with Joe Willet in Barnaby, an imperial institution sends young Walter Gay abroad; and Walter, like Joe, having escaped death on a foreign shore, returns wiser, stronger, and generally more mature, enabling him to achieve prosperity and happiness back in England. Dickens associates a number of businesses in Dombey with Britain's maritime commerce, including Sol Gills' marine store shop at one end of the social scale and, at the other, the mighty import-export firm of Dombey and Son, which despatches Walter to its overseas headquarters on the aptly named Son and Heir, which, like Dombey's financial empire, comes to grief.

Dombey and Son sends Walter to China for his success in life. After this single businesstrip abroad, he is posted to Britain, so that at this point his relation with the empire is broken. But it cannot be denied that he supports his family on his comfortable income from overseas commerce. After the manager Carker's death, his brother and sister anonymously keep Dombey supplied with their inherited money, for it was originally made by Carker's embezzlement from the House. So this money was also earned by overseas commerce. Solomon Gills' reestablishment of trade is owing to his old overseas investment. But all of them do not think that their lives are, more or less, dependent on imperial exploitations. [Tanaka 961-62]

Sadly, racial intolerance of the Major Bagstock variety continues to oppress religious, ethnic, and racial minorities in my own "native land" — a quotation from the Canadian national anthem which itself seems to disparage the rights, value, and identities of immigrants. Today's news stories in the aptly named Victoria Times Colonist on 24 February 2021 suggest the same problems with discrimination and differential treatment as those that inspired the Black Lives Matter movement. In the coastal port-city of Kitimat, for instance, with its obviously indigenous name, a pregnant young Native woman is turned away from hospital; the ambulance refuses to take her to the next medical facility, and her baby is stillborn. In another story, a municipal councillor of indigenous heritage (the north-coast Tsimshian nation) resigns two years into her mandate because of systemic racism. And in my own family my daughter-in-law, a woman of indigenous heritage, well-qualified but not as highly qualified as some, must go to court to fight for fair compensation after an automobile accident. Such injustices will continue as long as the Major Bagstocks of this world are allowed to hold sway.

Related Material, including Other Illustrated Editions of Dombey and Son

- Dombey and Son (homepage)

- Phiz's monthly illustrations (October 1846-April 1848)

- O. C. Darley's Frontispiece in the New York edition (Vol. 1, 1862)

- O. C. Darley's Frontispiece in the New York edition (Vol. 2, 1862)

- O. C. Darley's Frontispiece in the New York edition (Vol. 3, 1862)

- Sol Eytinge, Junior's 16 Diamond Edition Illustrations (1867)

- Fred Barnard's 61 Illustrations for the Household Edition (1877)

- Groome's illustrations of the Collins Pocket Edition (1900, rpt. 1934)

- Kyd's five for Player's Cigarette Cards (1910)

- Harry Furniss's 29 illustrations for the Charles Dickens Library Edition (1910)

Bibliography

Cohen, Jane Rabb. "Part Two: Dickens and His Principal Illustrator. 4. Hablot Browne." (Part 1). Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio U. P., 1980.

Dickens, Charles. Dombey and Son. With illustrations by H. K. Browne. The illustrated library Edition. 2 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, c. 1880.

__________. Dombey and Son. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr., and engraved by A. V. S. Anthony. 14 vols. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1867. III.

__________. Dombey and Son. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. 61 wood-engravings. The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1873. XV.

__________. Dombey and Son> Illustrated by W. H. C. Groome. London and Glasgow, 1900, rpt. 1934. 2 vols. in one.

__________. Dombey and Son. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. IX.

Kyd [Clayton J. Clarke]. Characters from Dickens. Nottingham: John Player & Sons, 1910.

Tanaka, Takanobu. "Empire, Demarcation, and Homein Dombey and Son." Lecture given at the Japan branch of the Dickens Fellowship. College of Culture and Communication, Tokyo Woman's Christian University. 9 October 1993. Pp. 947-965. http://www.dickens.jp/archive/ds/ds-tanaka-1.pdf

Tearle, Oliver. "Dombey and Son: The Themes of Dickens’s Railway Novel."Dispatches from The Secret Library. 2020. https://interestingliterature.com/2020/06/dickens-dombey-son-themes-analysis/

Vann, J. Don. "Dombey and Son, twenty parts in nineteen monthly installments, October 1846-April 1848." Victorian Novels in Serial. NewYork: Modern Language Association, 1985. 67-68.

Created 25 February 2021