n the first six chapters of Dickens, Death and

Christmas, Robert L. Patten has already analyzed the first of the the Christmas

Books, A Christmas Carol, written over the

course of October and November of 1843, as both a response to such contemporary issues as

Malthusian doctrine and the Hungry Forties, and a reflection of the meaning of Christmas, and

the Christian implications of Scrooge's moral and social "rebirth." He has also provided

an interesting discussion of the second in the series, The Chimes: A Goblin Story of Some Bells That Rang an Old Year Out and a New

Year In (1844). Although none of the four seasonal offerings that followed the

Carol has enjoyed the same enduring literary celebrity and popular

interest, each reflects the times in which it was

written: The Hungry Forties.

n the first six chapters of Dickens, Death and

Christmas, Robert L. Patten has already analyzed the first of the the Christmas

Books, A Christmas Carol, written over the

course of October and November of 1843, as both a response to such contemporary issues as

Malthusian doctrine and the Hungry Forties, and a reflection of the meaning of Christmas, and

the Christian implications of Scrooge's moral and social "rebirth." He has also provided

an interesting discussion of the second in the series, The Chimes: A Goblin Story of Some Bells That Rang an Old Year Out and a New

Year In (1844). Although none of the four seasonal offerings that followed the

Carol has enjoyed the same enduring literary celebrity and popular

interest, each reflects the times in which it was

written: The Hungry Forties.

The contemporary issues to which Dickens was responding in The Cricket on the Hearth (1845) are the basis for Patten's eighth chapter, "Chirping," which features ten of the fourteen original illustrations by three of the five talented artists who realised the characters and situations of the novella. These plates concern three interlocking subjects: the return of a long-long lost fiancé; a blind toymaker and her faithful father; and challenges to the happy marriage of the middle-aged Dorset carrier John Peerybingle and his young wife, Dot: John Leech, Daniel Maclise, and Richard Doyle.

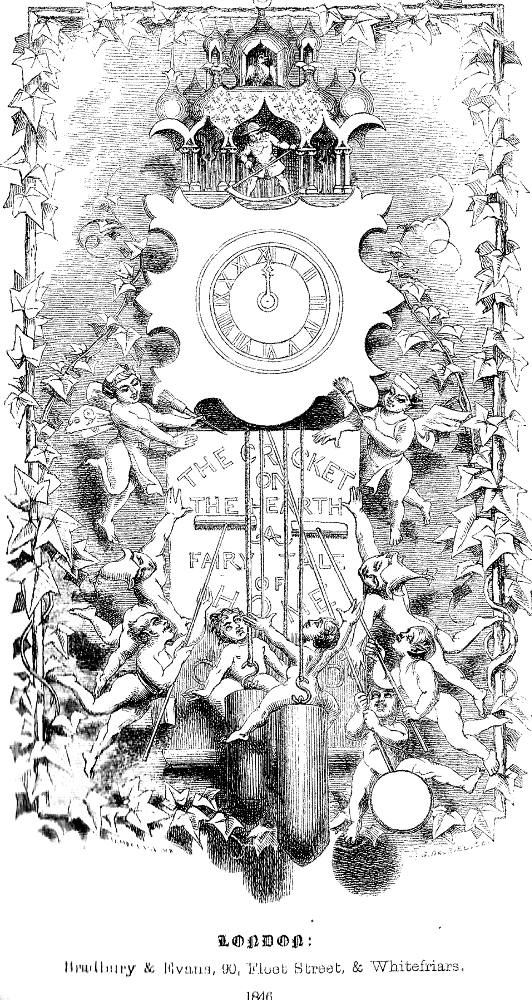

From left to right: (a) Scarlet-and-gold cover of with embossed fireplace motif and printed title-page of The Cricket on the Hearth (Bradbury and Evans, 1845). (b) Richard Doyle's Pre-Raphaelite frontispiece John and Dot Peerybingle before the Fire, depicting the rural, middle-class couple before the fire in their Dorset cottage as invisible fairies rock the cradle of their infant. (c) Daniel Maclise's ornamental title-page: The Dutch Clock.

These wood-engravings, dropped into the letterpress, underscore the seasonal novella's rural setting and the mixed nature of the work, which is both domestic comedy and melodrama. However, as Patten notes, there is one further ingredient, the seasonal theatrical experience of the children's pantomime, which had influenced one particular interpolated tale in The Pickwick Papers, Chapter XXIX, “The Story of the Goblins who stole the Sexton,” published in January 1837. Even if we fail to make such a connection today, it was nonetheless fairly obvious to London theatre-goers in late December 1845, for the husband-and-wife team of the Keeleys staged the officially sanctioned dramatic adaptation, The Cricket on the Hearth; or, A Fairy Tale of Home, a drama in three acts, at the Lyceum immediately following a pair of pantomime entertainments for the whole family, Dick Whittington and His Cat and Aladdin and The Forty Thieves (Bolton, 274). The first audience on December 20 were not likely to have read the novella as Chapman and Hall had just issued it that morning; but they were sure to understand the idiom of the short play, the contemporary pantomime, as Patten notes of various characters and plot elements, notably the vision of the Fairy Cricket and the concluding dance.

Patten on The Cricket and Domesticated Pantomime: "Chirping"

What pantomime did was half-way to domesticating the energies of carnival. With The Cricket, we can discover many of the pantomimic elements: a heavy father Tackleton standing in the way of the young lovers, a person in disguise, an almost talking dog Boxer, mysteries and exposures of tricks and deceits, music of different kinds and played with different instruments to different ends (the celebrants that Dot declines to join are apparently more free-spirited singers than a married housewife's music associated with a chirping Cricket and a tea kettle), and a society reinstituted at the close, with changes: Dot's parents, the stiff old lady Mrs. Fielding, a perfect cross-dress role with her huge caps and stiff back, dancing away with Gruff and Tackleton, a clown always endangering self or baby and wearing clothes having no relation to its body personified, in a way, by Tilly Slowboy (most of the clowns, including Grimaldi and his son, were men), and even Caleb Plummer, old and tired and poor and creaky, can join Tilly in diving in among all the other couples and causing concussions.

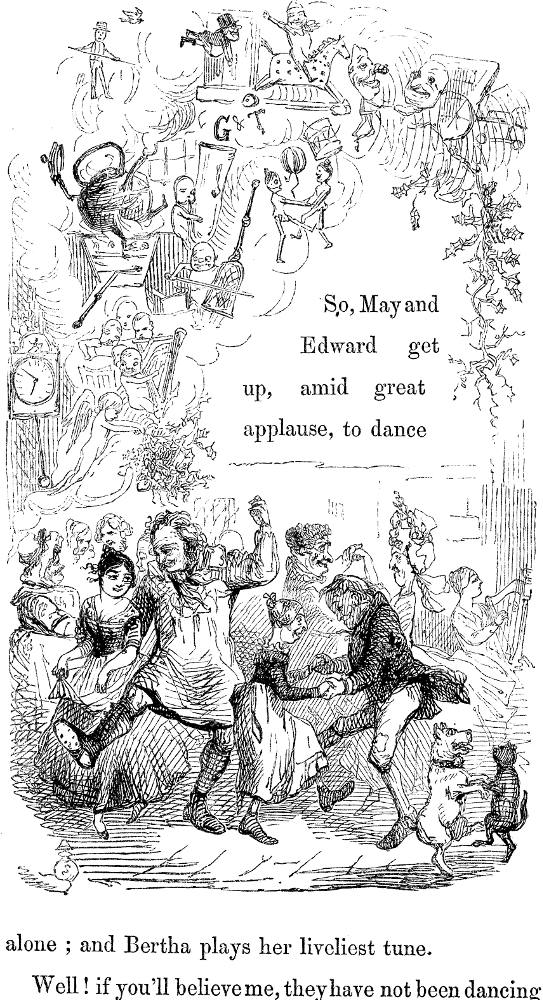

The unrealistic aspects of this tale, the human beings and animals that seem to be live copies of the figures, dolls, gentlemen in doorways, inhabitants of the home-like ark with the door knocker, and other products of the Tackleton toy factory, may be understood as figures in a kind of novelistic pantomime. A melodramatic [197/198] pantomime, sorting out figures in moral terms, arousing strong emotions in the audience from what they do, and being restored to an orderly society of the whole at the end. Boxer included — dancing with a cat in the lower-right corner of the last plate. That's Leech's tribute to Phiz's dancing animals in the illustration to the Christmas number of Pickwick, at Dingley Dell farm, a serial Leech applied to illustrate, and was turned down by Dickens.

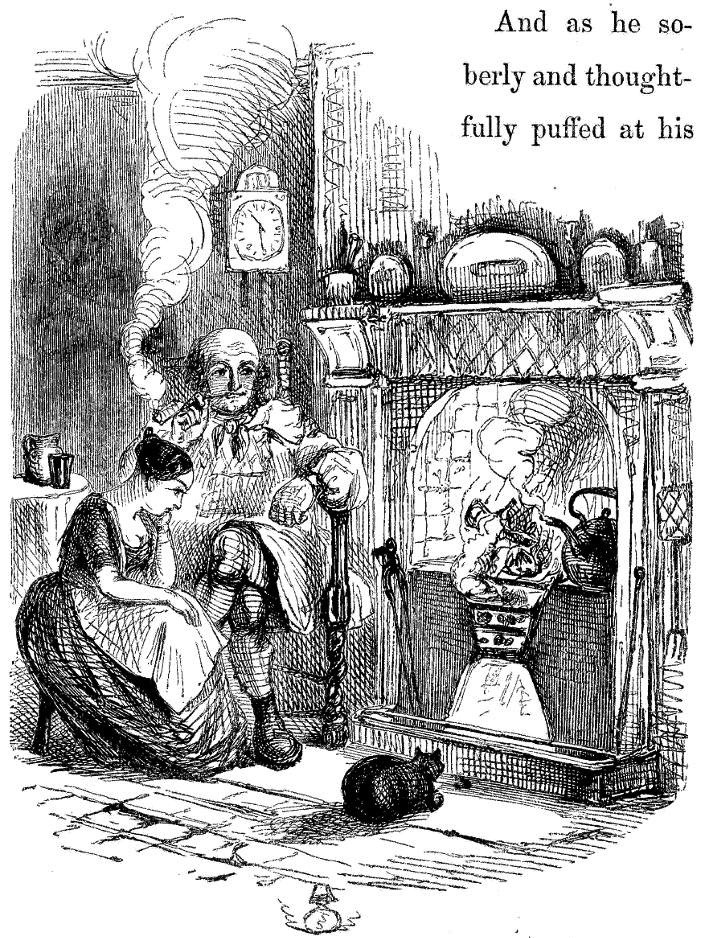

John Leech's tranquil fireside with cat and kettle, John and Dot, in which the smoke from John's pipe visually echoes the steam rising from the kettle, as if hearth and pipe are twin emblems of domestic felicity.

So carnivals and pantomimes and even Pickwick and Pic Nic course through the veins of this little book, almost instinctively from the start of composition by Dickens conceived for its adaptation into three acts for staging at Christmas. But he goes further. He contains pantomime within the middle-class home. At the center of that home is the hearth warming the public and family room, holding the tea kettle. Around, on the mantel and on the walls and on the tables, are the family's homely, comforting objects, domestic icons. There's no picture of Jesus, and certainly no actual Lares and Penates in the Perrybingle home: but nature and memories and imagining populate the space with voices and images that hold memories and dispense advice. To a John who might believe his wife unfaithful, to a wife and son, to a host of visitors who bring assorted gifts, to toymakers transforming frolic and folly into benign and malign playthings, and to a foggy world that, if one takes the trouble, will reveal even fairy rings. Pantomime admits any number of genres, from tragedy to comedy, romance to religion. [197-198]

John Leech's exuberant tailpiece, The Dance, depicts the celebration in the humble Dorset cottage of toymakers Bertha and Caleb Plummer.

Links to Related Material

- Illustrations of Dickens's The Cricket on the Hearth

- Commentary on The Cricket on the Hearth

- The Costuming and Set Designs of Plays Adapted from Dickens's Christmas Books: Realisations of the Illustrations

- Review of Robert L. Patten's Dickens, Death and Christmas

The History of Pantomime

- The Development of Pantomime, 1692-1761

- Victorian Pantomime

- Festive Fare: A Review of Jeffrey Richards' The Golden Age of Pantomime: Slapstick, Spectacle and Subversion in Victorian England

- Joseph Grimaldi, satire, and pantomime

- Dickens's The Christmas Books, Plays, and the Pantomime

Bibliography

Dickens, Charles. The Cricket on the Hearth. A Fairy Tale of Home. Illustrated by John Leech, Daniel Maclise, Richard Doyle, Clarkson Stanfield, and Edwin Landseer. Engraved by George Dalziel, Edward Dalziel, T. Williams, J. Thompson, R. Graves, and Joseph Swain. London: Bradbury and Evans, 1846 [December 1845].

Bolton, H. Philip. "The Cricket on the Hearth." Dickens Dramatized. Boston: G. K. Hall, 1987. 273-295.

Parker, David. Christmas and Charles Dickens. AMS Studies in the Nineteenth Century, No. 34. New York: AMS Press, 2006.

Patten, Robert L. Dickens, Death, and Christmas. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2023. [Review]

Created 22 February 2024