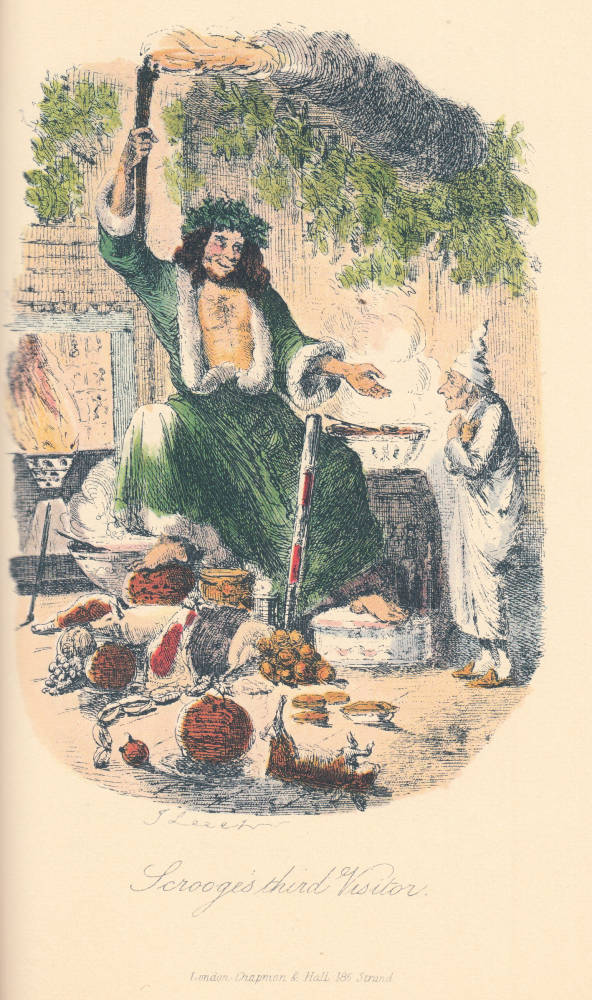

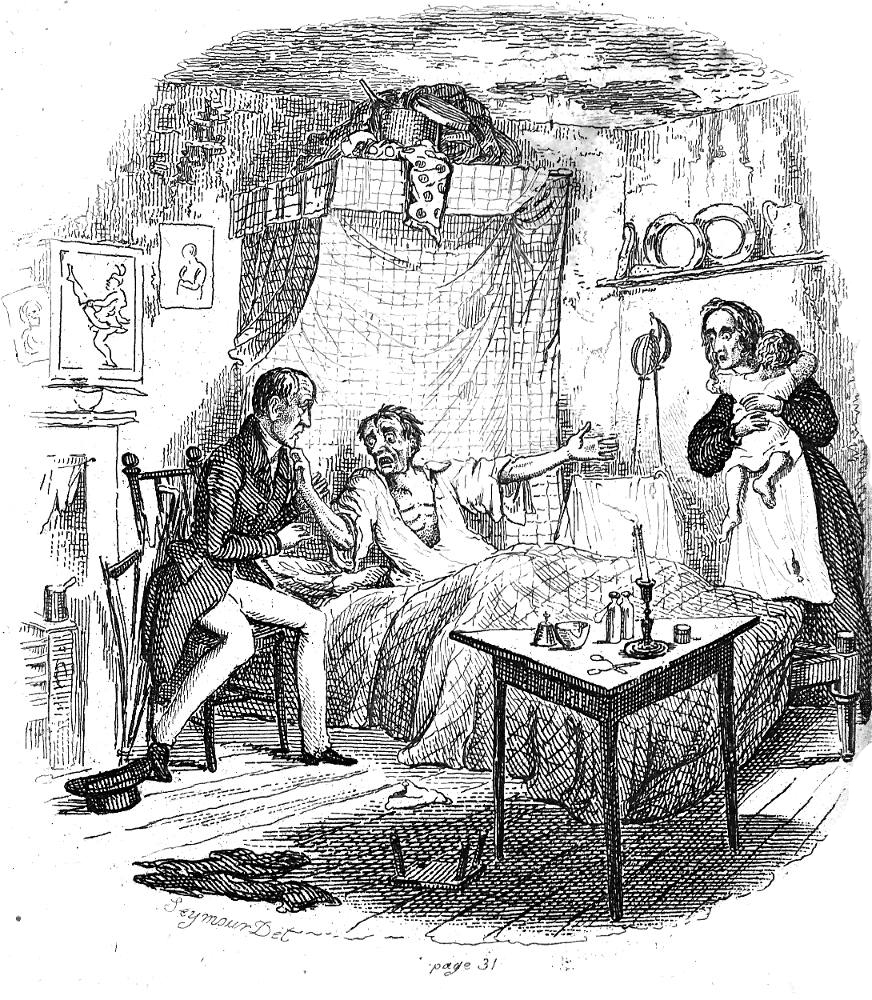

Left to right: Jacket image by John Leech (1843): Scrooge's Third Visitor, from Dickens's A Christmas Carol. 31 December 1836 seasonal illustration by Phiz, The Goblin and the Sexton for the Ten Part of Dickens's The Pickwick Papers. George Pinwell's Leaving the Morgue, from The Uncommercial Traveller (1868). Scrooge's encounter with the Third Spirit at his own grave in Dickens's A Christmas Carol, Stave IV, by John Leech (1843). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

ickens, contends Robert L. Patten, was not so much concerned with

striking a literary "blow for the poor" or musing upon

"The Condition of England" in the Carol. Rather, like the interpolated Pickwick tale "The Story of the

Goblins Who Stole a Sexton" (Chapter XXIX), A

Christmas Carol is a meditation on how death, particularly the untimely death

of children, makes us value life more dearly, and even attain a fresh understanding of

ourselves and our relationship with the rest of humanity — a Scroogian epiphany.

Certainly, in its reaffirmation of the interdenominational Christian message, A Christmas Carol is indeed a paean to the middle-class and urban

spirit of Christmas. According to Patten, we may better understand the novella's complex

meanings if we view it in the context of Dickens's attitudes towards — and obsessions with

— such institutions as the Paris Morgue, an account of which in his "Prologue"

(vi-ix) Patten emphasizes when considering Dickens's fascination with death and

the dead two decades after the publication of the Christmas Books.

ickens, contends Robert L. Patten, was not so much concerned with

striking a literary "blow for the poor" or musing upon

"The Condition of England" in the Carol. Rather, like the interpolated Pickwick tale "The Story of the

Goblins Who Stole a Sexton" (Chapter XXIX), A

Christmas Carol is a meditation on how death, particularly the untimely death

of children, makes us value life more dearly, and even attain a fresh understanding of

ourselves and our relationship with the rest of humanity — a Scroogian epiphany.

Certainly, in its reaffirmation of the interdenominational Christian message, A Christmas Carol is indeed a paean to the middle-class and urban

spirit of Christmas. According to Patten, we may better understand the novella's complex

meanings if we view it in the context of Dickens's attitudes towards — and obsessions with

— such institutions as the Paris Morgue, an account of which in his "Prologue"

(vi-ix) Patten emphasizes when considering Dickens's fascination with death and

the dead two decades after the publication of the Christmas Books.

On one particular night at the end of the year 1867, among the viewers jostling for space and better sight lines was a tall gentleman — 5' 9", about 3" taller than the average male of the period —, bearded, wearing fashionable clothing and a top hat, who described himself in several writings as a frequent visitor (Figure P.2). He was Charles Dickens, and it was Christmas week. [viii]

A Note on Patten's Illustrations

Some seventy illustrations, including all of Leech's plates for the Carol, appear among the seventy illustrations spanning the first ten chapters. The final pair, "Thereafter" (pp. 276-301) and "Endings" (pp. 302-315), are unillustrated, despite the fact that the Carol remains Dickens's most illustrated text, thanks, in part to later editions specifically aimed at child-readers. Surprisingly, some reproductions are not as good as they might be — for example, Leech's frontispiece and title-page (76), the photograph of a pair of facing pages. Generally, however, the standard of reproduction is high, and Patten effectively achieves his goal of showing "how the text and illustration interact" (xvii), He does say himself that "many are not as crisp and clear as they would have been in the first editions," explaining that he was compelled to use images from the 1954 New Oxford Illustrated Edition because COVID made it difficult for him and the publisher to obtain sufficiently dense scans from the first editions of the five Christmas Books (1844-48). There remains one unexplained discrepancy: although the 1843 Leech published, hand-tinted plate Scrooge's third Visitor features a Spirit of Christmas Present clad in green, suggesting his "ever-green" nature and vigour, Patten's jacket image clearly shows the same figure clad in crimson, as if Leech was anticipating Father Christmas rather than the "jolly giant glorious to see" in his fifth illustration. Patten notes that the error is not replicated in the published illustration, but is restricted to "his watercolor drawing for the illustration" (92). Patten alludes twice to "John Leech's incorrect coloring of the Ghost of Christmas Present's robe" (pp. xi-xii), but does not elaborate on how the Morgan Library and Museum has helped him to resolve this issue as he has done, with a scarlet and ermine-trimmed robe for the bare-footed, bare-chested giant. After all, Dickens is unequivocal in his description: "It was clothed in one simple deep green robe, or mantle, bordered with white fur" ("Stave Three: The Second of the Three Spirits," 78). To distinguish the published version from the original watercolour workup, Patten terms the image on his cover simply Scrooge's Third Visitor, whereas the published, hand-tinted version is The Second of the Three Spirits or Scrooge's Third Visitor (facing page 78, visually realising the passage of description on page 77).

Prologue to A Christmas Carol: Chapters 1 through 3

Relevant illustrations for Dickens's handling of death, 1836-1843: Marley's Ghost by John Leech in A Christmas Carol, "Stave One." George Cattermole's iconic At Rest (Nell dead) in The Old Curiosity Shop (30 January 1841). Robert Seymour's The Dying Clown in The Pickwick Papers (April 1836). George Cattermole's dramatic Sir John Chester's End in Barnaby Rudge (27 November 1841). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Three chapters prepare us for Dickens's emotional, psychological, cultural, and dramatic examinations of death in the fourth through the sixth, "Dickens Contemplates Sledge Hammer Blows" (pp. 46-63) through "Marley Was Dead" (pp. 75-126): 1. "A Frequent Visitor" (pp. 1-15), 2. "Dickens's Christmases to 1836" (pp. 16-26), and 3. "Pickwick and After" (pp. 27-45). The seminal moment, which Dickens delayed writing as long as possible, was the death of Little Nell in The Old Curiosity Shop since it painfully recalled for him the death of his beloved sister-in-law, seventeen-year-old Mary Hogarth on 7 May 1837.

The three-page "Prologue" (pp. vi-viii) highlights Dickens's life-long fascination with the Paris Morgue on the Ile de la Cité, and the first chapter, "A Frequent Visitor," with suitable pictures, follows this obsession through The Pilgrim Letters, sundry Household Words and All the Year Round articles, notably the essay "Travelling Abroad" in The Uncommercial Traveller (7 April 1860).

Dickens not only explores the psychological results from viewing a terrible object on himself, but also on a child; and while the lesson he derives appears to apply to parents, the warning that it "would be difficult to overstate the intensity and accuracy of an intelligent child's observation" could well apply to the "very queer small boy," figure of his own young self, and to experiences, like that in the blacking warehouse, that he had forced himself to recollect, write down as the autobiography given to Forster, and reconstruct for David Copperfield, a decade earlier. [13]

The commentary here showcases Patten's breadth of reading in Dickens's works which enables him to make connections and see trends across Dickens's five decades of professional writing. In particular, Patten is able to utilize little read journalistic pieces such as "Some Recollections of Mortality" (All the Year Round, 16 May 1863) to comment upon the effectiveness of such scenes as Magwitch's rising up from the grave of Pip's parents at the opening of Great Expectations in the 1 December 1860 issue of All the Year Round.

The second chapter, "Dickens's Christmases to 1836," is necessarily biographical rather than literary in its orientation. However, Dickens continued to reflect upon his own childhood throughout his later life, and to mine such childhood experiences as the death of a younger brother, Alfred Allen, in September 1814 from hydrocephaly. But Patten foils such traumatic events as John Dickens's incarceration for debt with family birthdays, Twelfth Night celebrations, and the White Christmases of 1820 and 1830. Rightly, argues Patten, Dickensians regard the "Christmas Dinner" sketch (the second in the "Characters" section of Sketches by Boz, originally published in Bell's Life in London on 27 December 1835) "as the beginning of Dickens's stories about Christmas" (21):

It features the coming-together of an extended family, the healing of ruptured relationships, the multigenerational expectations and hospitality, a turkey and an enormous pudding, which occasions "the clapping of little chubby hands, and kicking up of fat dumpy legs," after-dinner wine and ale, speeches and songs, and "rational good will and cheerfulness." [21]

As Patten notes, since the first three issues of the January 1836 Bell's Life in London sold 600,000 copies, such sketches of London's upper-lower and middle-class life must have established Dickens as a perceptive, entertaining young author as he deftly encapsulated in seasonal offerings "the feelings of these classes that might be generated by Christmas and New Year's. And he is beginning to shape narratives around the polarities generated by the mixture of birth and death, and the life of remembering and enjoying and expecting — engaging past, present, and future — that runs between, on both occasions" (25).

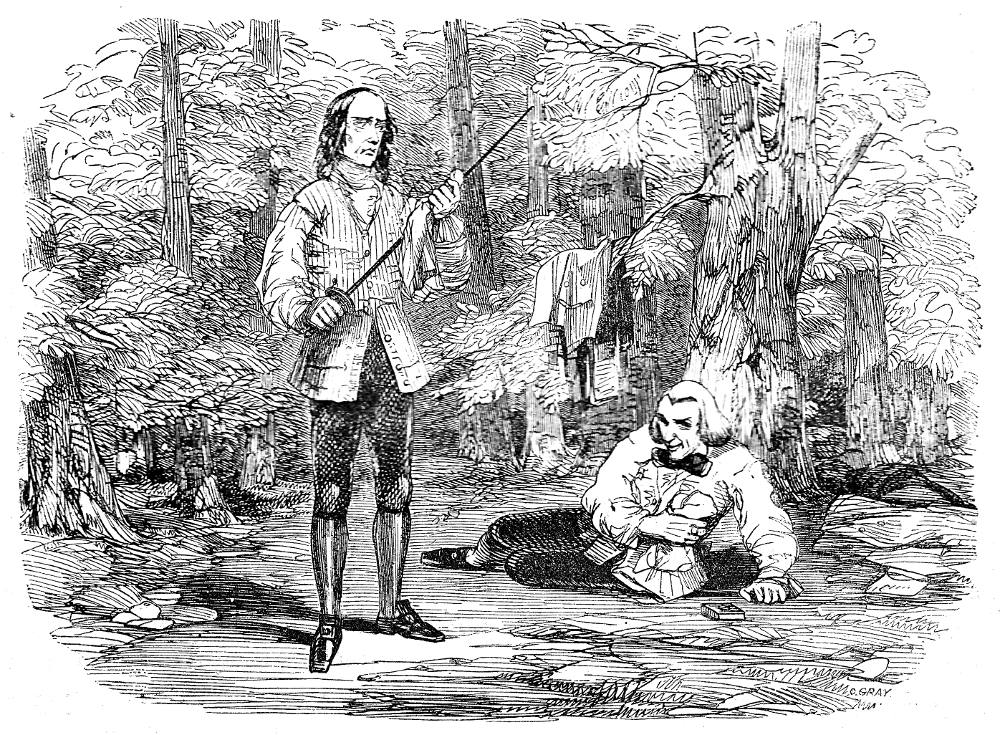

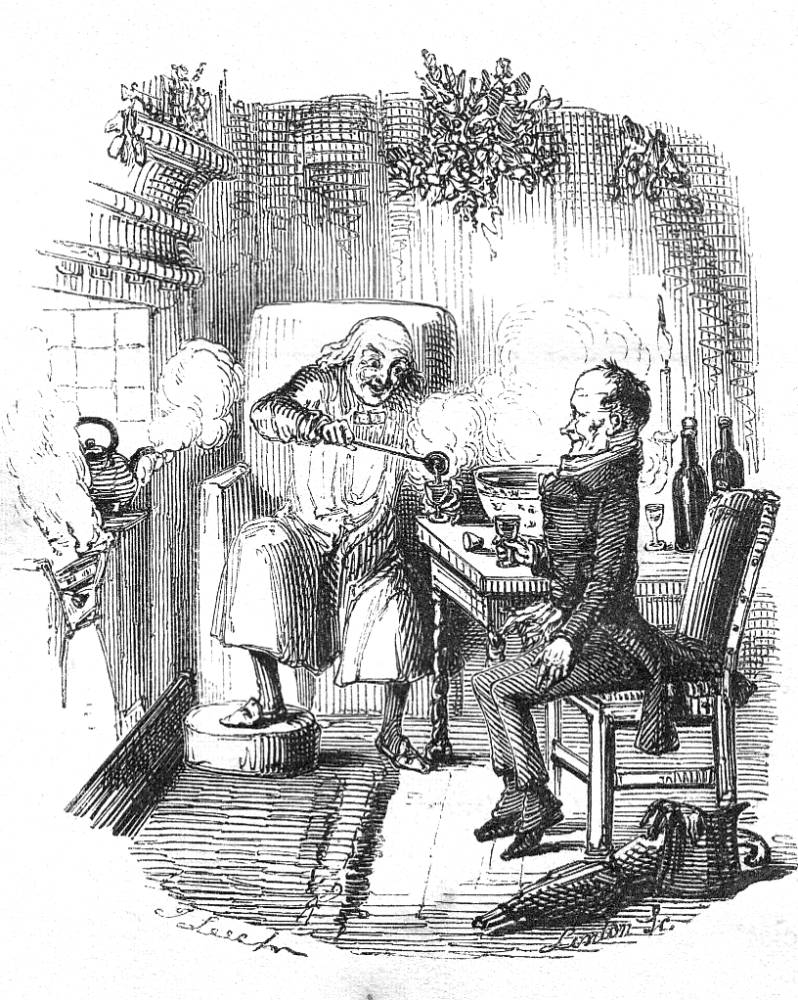

Left: Phiz's convivial Christmas Eve at Mr. Wardle's, Chapter XXVII (January 1837 "Christmas" number): Figure 3.1 (p. 29).

Since Pickwick, however, marked Dickens's first major appearance on London's literary scene, Patten devotes an entire chapter to its relationship to the Christmas Books of the following decade. As Patten notes, the Pickwick "Advertiser" was not the chief innovation of publishers Chapman and Hall in issuing this novel in monthly parts. Real time and fictional time could coincide, and readers could reflect on Christmas and celebrate New Year's in the part-publication both within and outside the work, issued in twenty monthly parts at a shilling a number, a format accessible to readers even from the lower-middle-class. However, Dickens's treatment and context for "Christmas at Dingley Dell" are hardly urban and contemporary:

How might the season of Christmas, which could be recounted in the tenth Part issued just before New Year's Day, be incorporated? The solution was a great gathering of characters at Manor Farm, for feasting and entertaining on an enlarged and more country pattern than the urban Christmas in Sketches. Holly and evergreens decorate the long, dark-paneled sitting room with a high chimneypiece. On December 23rd, a morning church wedding followed by a hearty breakfast and dinner, many toasts, and heated dancing take place (a more elaborate festival than those in the Bell's Life sketches); quite a bit of flirting occurs in dim corners. On Christmas Eve, Manor Farm keeps the immemorial customs of Wardle's forefathers in the large kitchen where the master of the house hangs a huge branch of misteltoe (Figure 3.1). [28]

Right: Cruikshank's uproarious tale-telling by the fire in the Title-page Illustration for German Popular Tales (London: C. Baldwyn, 1823; James Robbins, 1826). Figure 3.2 (p. 30).

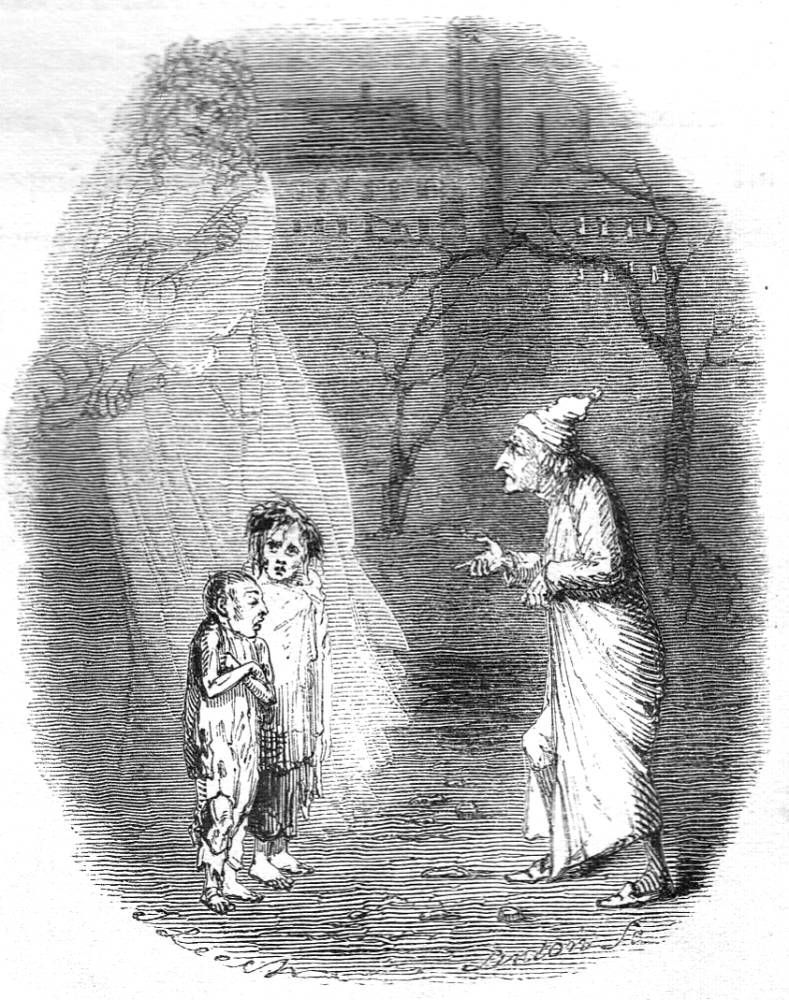

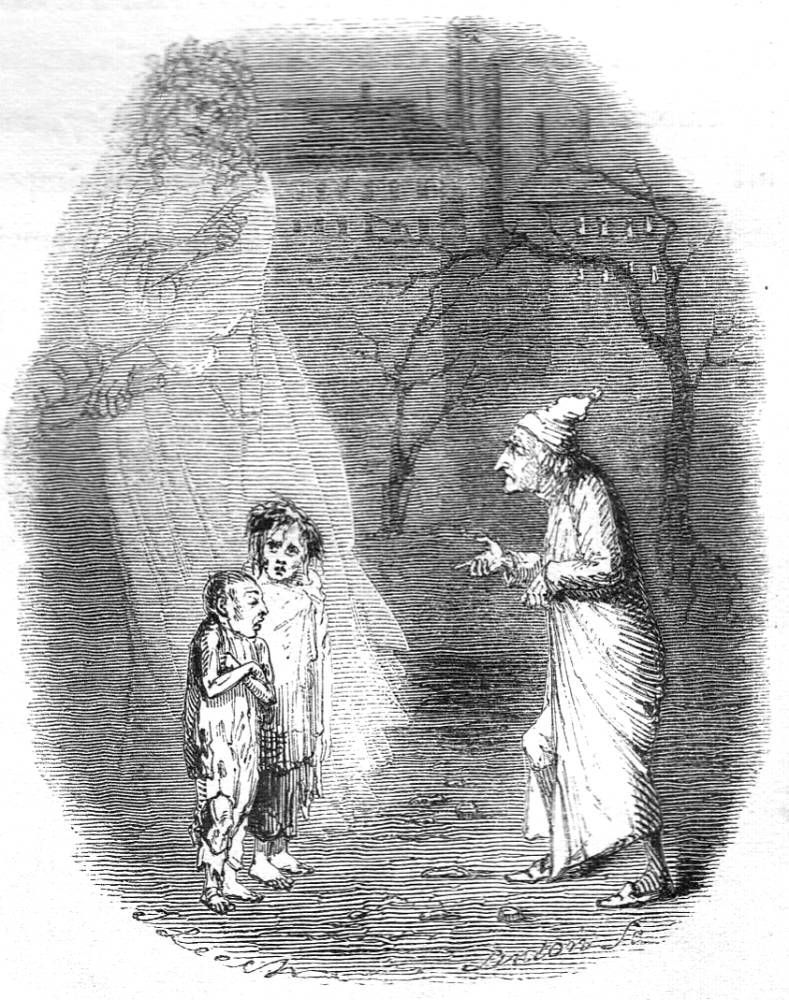

Consequently, we can readily see how the Dingley Dell Christmas informed the Christmas of urban businessman Ebenezer Scrooge, his jovial nephew Fred, and the high-spirited Cratchits. What we are not seeing, says Patten, is a German "ghost story" translated into a London context — enter "The Goblin and the Sexton," an interpolated tale, re-told by Wardle, but based on a telling by Wardle's father, who in turn heard it from village folk in his youth. The origin of such "scary stories for Christmas" is not English at all:

Added to [the traditional speeches and toasts at the Christmas table] . . . is a different tradition, recently invigorated in Britain by the first English translation of the Brothers Grimms' fairy stories, illustrated by George Cruikshank, in 1823 and 1826 (Figures 3.2 and 3.3). These were imagined as grandfathers' and nurse's stories told to wondering children gathered around the hearth. Scary stories, featuring goblins and ghosts and magical creatures, inspiring momentary fear, even terror, dissipated afterward by the companionship and the comfort of the setting. [pp. 30-31]

Thus, in the Christmas number of Pickwick the social gathering and the supernatural tale co-exist, dividing readers' interests, but in the Carol Dickens brilliantly synthesizes these constituents though dramatisations of remembered Christmasses past, the vivid Christmas present, and the nebulous Christmas Yet to Come, over all three of which Death lurks.

Fictional deaths continued after his return from America. Many are consigned to a grave in Martin Chuzzlewit (1843-44), Dombey and Son (1846-48) opens with a death, and Part IV for January 1847 was supposed to present another, very moving one. But when he tried to write it in December 1846, he could not. He redesigned the January number and postponed plunging back into grief once again until after New Year's 1847. Twenty months later, on September 2, 1848, his beloved sister Fanny died. [44-45]

Patten's analysis, with its bringing together of relevant data from Dickens's lfe, is both moving and convincing.

On A Christmas Carol: Chapters 4 through 6

Relevant illustrations by John Leech for A Christmas Carol: The Ghosts of Departed Usurers, or, The Phantoms (wood engraving dropped into the letter-press, "Stave One," p. 37. Ignorance and Want in "Stave Three," wood-engraving dropped into the text of p. 119: note the withered trees and factories in the backdrop. Scrooge and Bob Cratchit, or, The Christmas Bowl in "Stave Five: The End of It," p. 164. Right: The hand-tinted type-set title-page. [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

When he addresses ignorance and want in the Carol," Patten suggests, "his means are very simple: the Ghost of Christmas Present merely opens his cloak to display two ragged children who, without proper care, will destroy the world. Behind that, as his contemporary readers would know, are all the flaming disputes that endlessly retarded provisions for the health, welfare, and education of Britain's swelling population of young people" (63).

Right: Leech's celebrated exposé of the government's failure to enact the regulatory provisions of the 1836 Factory Act, Ignorance and Want.

The true meaning and Dickens's subtextual intentions behind Leech's grim Ignorance and Want in "Stave Three, The Second of the Three Spirits," become much clearer once has fully digested the many topical allusions in Chapter 4, "Dickens Contemplates Sledge Hammer Blows" (pp. 46-63) from 1841 through 1843. Patten elucidates how such matters as international and domestic copyright (brought home to Dickens by the immediate theft of the Carol), the deplorable working conditions in Britain's mines and factories, and the political maneuvering between Nonconformists and the Established Church of England over the management of the kinds of Ragged Schools that Dickens visited not far from his Doughty Street home at Field Lane in Saffron Hill have impacted his composition of A Christmas Carol in the autumn of 1843. Busy as he was at that time with Martin Chuzzlewit, says Patten, Dickens even parodied the report of the Royal Commission into the working conditions in mines, collieries, and factories (published in 1842) in A Report of the Commissioners appointed to inquire into the Constitution of the Persons variously engaged in the University of Oxford. However, all of these allusions and quotations have but one intention in Patten's fourth chapter: to shed light on the rampant exploitation by ruthless peers (particularly in Northumberland and Durham) of the burgeoning population of children and adolescents working up to fourteen hours daily without any provision for secular or religious education, reflecting Dickens's own exploitation as a boy-worker in the Hungerford Stairs blacking factory. He could certainly identify with the child haulers and trappers in the collieries, and with the seamstress in Thomas Hood's "Song of the Shirt," published in Punch 5 (December 1843), 260. And Dickens had recent, first-hand experiences upon which to draw — a walking tour of Cornwall and its mines with Forster, Daniel Maclise, and Clarkson Stanfield.

Patten delivers the crux of his argument about his former partner returning from the dead to rescue Scrooge from his money-grubbing, Malthusian morality in the long sixth chapter, "Marley was Dead" (pp. 75-126). The paragraph ending "Old Marley was dead as a door-nail" which opens the novella sets the keynote:

With exceptional economy masquerading as elaboration, Dickens provides a character who is dead, the immediate legal and religious consequences of his decease, the funeral, the chief mourner, Scrooge's occupation — finance — and his reputation. And then, recalling a dream he had had recently about someone who was "dead as a door-nail," Dickens repeats the phrase. All written fluently, with much hiding of implication in the "spaces" between the lines. [77]

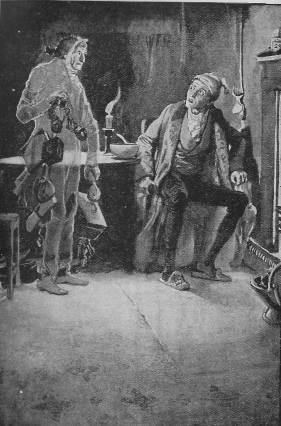

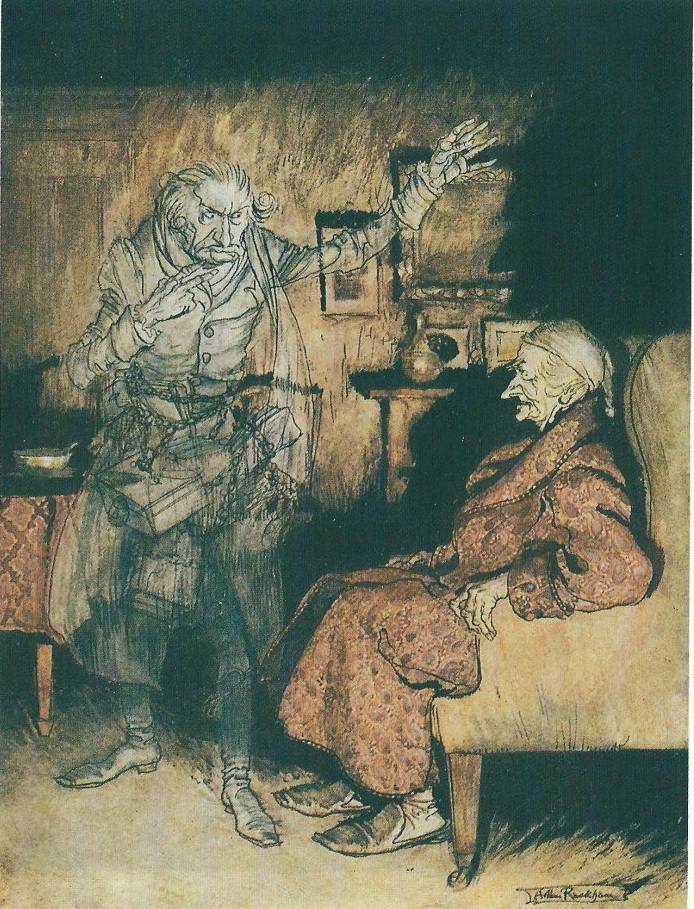

Relevant illustrations by post-Leech artists for A Christmas Carol: Charles Green's Marley's Ghost (circa 1912), frontispiece in the Pears' Centenary Edition. Fred Barnard's Household Edition Marley's Ghost (1878), "Stave One," facing p. 78. He felt the chilling influence of its death-cold eyes, lithograph by A. A. Dixon (1906). "How now," said Scrooge, caustic and cold as ever, "What do you want with me?" by Arthur Rackham (1915). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Dickens took a piece of paper, placed it on his desk, dipped his quill in black iron-gall ink, and wrote

Left: Arthur Rackham's line-drawing captures Marley's dour expression as he appears before Scrooge as a door-knocker: Marley's Ghost (1915).

Stave I [double underlined]

Old Marley's Ghost [double underlined]

He already knew that he was going to riff on "Carol" by dividing the tale into "Staves." A stave might be a staff, a plank, or post, or it could be the thin strips of wood that can be warped around a barrel, or, as in this case, the five lines and four spaces on which musical notes are written. Dickens may have already figured that there would be five "Staves" of writing as there are five lines in a stave of music. [76]

Patten poits out, however, that this is not a lachrymose or excessively sentimentalised death (not like Smike's, or Nell's, or even Mary Hogarth's). This spirit has returned from Purgatory like the Ghost in Hamlet: "he is the ghostly mentor," but not the father-figure come expressly to warn about villainy in the head office, foreign competition, or the truth about his death. But his chains, padlocks, and ledgers do constitute a warning since Scrooge wore fetters equivalent to these seven years ago. "Marley wants to give Scrooge a chance to live" (79) unfettered, that is, to rejoin the human family, rather than continuing to live a solitary oyster's existence. "Dickens converts ghost from a scary or retributive figure to one trying to make amends" (79).

If Dickens's real target is greedy industrialists and exploitative colliery-owners, Patten asks, why then has he made Scrooge a capitalist and financier, well-known on the London Exchange, but having one employee? "Why did Dickens make him a London financier? For one reason, Dickens, in all his diatribes against money-grubbing owners, deals with the moral and spiritual deficits, not the material and bodily injuries. He basically wants reform of minds and souls" (80) rather than better working conditions, higher hourly wages, and adherence to safety standards. Whereas his former business mentor, Old Fezziwig, had a warehouse, and accounting department, and numerous employees, Scrooge has just the much-put-upon Bob Cratchit. "Scrooge and Dickens deal in paper, whose value is a product of their character and hand" (81). But that hardly explains why Dickens did not identify Scrooge with the abuses of Britain's industrial system — although he certainly identifies Scrooge as a Malthusian or Utilitarian in his interview with the charity solicitors. (After all, the only way to assure an adequate supply of food is to "reduce the surplus population.") The ghost of his partner has no sooner appeared as a door-knocker and then rattled his chains than he begins his "spiritual" mission to reclaim Scrooge, a good man of business, and transform him into a good man whose "business" is mankind:

Marley's understanding now of "business" is vastly more comprehensive than mere trade: it is the business of mankind to cultivate and sustain community. The taxes that Scrooge pays [including the "Poor Law Rates"] are only a portion of what he owes, personally as well as financially, to his neighbors and strangers alike. The population of the whole World as an Ocean is a metaphor Dickens employs more than once. [82]

Right: Leech's Scrooge Extinguishes the First of the Three Spirits (woodcut dropped into the text; tailpiece for Stave Two, "The First of the Three Spirits, 73).

There is much to commend here, and much more detail in his chapters than this account can show. Patten's incisive and insightful analysis of the educational agendas of the three Christmas Spirits cleverly balances the nature of British nineteenth-century celebration of the Winter Solstice with the Christian doctrine of Resurrection. And accompanying his acute analysis Patten offers the tailpiece of Scrooge's extinguishing the Spirit of Past under his own snuffer, as if further scenes — further "enlightenment — engendered by visiting painful scenes from his own past will simply be unbearable. As Patten puts it, "Scrooge can't bear any more; the lessons are too difficult to tolerate" (88).

what does this light signify? Is it the imperishable light of Chistmastide? Has it somehow to do with Christ and the divine, often defined by light, and never more clearly to the disciples than at the moment of His transfiguration Dickens doesn't parse this phenomenon into any particular interpretation: it's just light. [89]

Thus, we can see it as indicative of "The Light of the World," the everlasting message of Christ, or the light of revelation, or the enlightenment Scrooge experiences by reviewing his own past and participating vicariously in the lives of others. This includes the family life of his former fiancée, Belle, whom he gave up for his Golden Idol, that is, in order to pursue wealth over the consolations of hearth and home. To emphasize the thematic importance of this tailpiece as an image of Scrooge's repressing distressful memories, Patten has increased scale, giving it two-thirds of page 89. "We're transported back into the present of the first Stave, into Scrooge's bedchamber, and into a world where, whether Scrooge knows it or not, while on the winter solstice light is diminished, it will not, cannot, be extinguished."

Patten admirably analyses the natures of the two family gatherings which the Spirit of Christmas Present enables him to attend, unseen: the joyful Cratchit family celebration (which comes off without a hitch, despite Martha's concern that somebody may steal the pudding while it's steaming in the wash-house) and the rollicking young adult party of Scrooge's upper-middle-class nephew, Fred, with a dinner "far more substantial than the Cratchits" (100), music, dancing, forfeits, and flirting. Patten also admirably points out how the Spirit's observation about Tim's absence from the chimney-corner by next Christmas serves as a rebuke yo Scrooge's Malthusian sympathies.

Gabriel Grub, hand, sexton's spade, burial, Marley, music, cultivation of a different plant than treasure chests: the imagery, motifs, themes, are blended with such effortless garden-variety prose that the full register of their significations can easily be missed by the mind while piercing the heart. [95]

Although Dickens offers no concluding celebratory dance of the characters of all degrees here (as he does in the remaining Christmas Books perhaps with an eye to theatrical dramatisation), the effects of music are particularly evident at nephew Fred's, where Scrooge joins the merriment at the end of the fifth Stave, signalling his social, familial, and spiritual redemption and reintegration. What separates the account of Scrooge's experiences with the previously ghostly entities (Marley, Christmas Past, and Christmas Present) from his journeys with that final, shrouded Spirit of Christmasses Yet to Come is an absence of voice: the dimly apprehended Future merely shows Scrooge various scenes associated with Scrooge's own death, and that of Tiny Tim. The somewhat muted voice of Dickens's traditional storyteller is still present, but this voiceless spirit does not interact with Scrooge in dialogue — indeed, Scrooge often has to speak for him:

Instead, Scrooge hears how a story of a life in the future is being told by others, now that its end has been accomplished. (Though at first he only knows that some man's end is being discussed, while readers feel they know more.) And these speculations are rather like the stories the speculators told about the corpses in the Morgue. In this future, . . . death releases the other stories that might be told about the deceased's previous life and future destination. [103]

The comic byplay at the rag-and-bone shop involves the ultimate disposition of Scrooge's personal effects by the human vultures — appropriated "But not stolen, according to their rendering of accounts" (103) by the disreputable owner of the depot, Mrs. Dilber, the laundress, the charwoman, and the undertaker's man. "The next obituaries are unvoiced" (104), but highly instructive for Scrooge, whose eyes are opened at last to the consequences of his lack of charity, and his failure to engage with the rest of humanity. Requesting scenes of compassionate and tender feeling, what the Spirit provides him has nothing to do with his grieving relatives; rather, he overhears the dialogue between Caroline and her husband, Scrooge's debtors for whom the miser's death brings reprieve, before he witnesses the aftermath of Tiny Tim's death at the Cratchits. "Dickens has often before asserted that painful memories, in time, under retrospection, take on a more pleasant aspect and aid to one's education about life. That is to be a theme and wished-for result of sad events in all five of the Christmas books" (106).

The first Christmas Book ends with Scrooge's epiphany as the shrouded Spirit of Christmases to Come shrinks and collapses as Scrooge awakes in his own bed on Christmas morning, reinvigorated: "Ownership has returned, the property and lodgings still belong to the live body; they are not dispersed to other tenants, a rag and bone shop, or buried under a stone in a rank and rancid graveyard" (113). Marley and the Spirits have granted the Miser the time he needs to make amends to those whom he has wronged and those whom he has ignored: "time for Scrooge to revisit his past life, get back in touch with the generous, loving, and — importantly — playful and imaginative boy who consoled his loneliness with reading and the characters who came to him then" (113-14). This thoughtful critique refreshes our response to one of the most familiar works in our literary landscape.

Links to Related Material

Bibliography

Dickens, Charles. The Battle of Life: A Love Story. Illustrated by Daniel Maclise, Richard Doyle, Clarkson Stanfield, and John Leech. London: Chapman and Hall, 1846.

_____. A Christmas Carol. Illustrated by John Leech. London: Chapman and Hall, 1843.

_____. The Chimes: A Goblin Story of Some Bells That Rang an Old Year out and a New Year in. Illustrated by John Leech, Richard Doyle, Daniel Maclise, and Clarkson Stanfield. Charles Dickens: The Christmas Books. Intro. and notes by Michael Slater. Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin, 1971. Rpt., 1978. Vol. 1: 137-266.

_____. The Cricket on the Hearth: A Fairy Tale of Home. Illustrated by Daniel Maclise, Richard Doyle, Clarkson Stanfield, John Leech, and Edwin Landseer. London: Bradbury and Evans, 1846.

_____. The Haunted Man and The Ghost's Bargain. Illustrated by John Leech, Frank Stone, John Tenniel, and Clarkson Stanfield. London: Bradbury and Evans, 1848.

_____. The Haunted Man and The Ghost's Bargain. Illustrated by John Leech, Frank Stone, John Tenniel, and Clarkson Stanfield. London: Bradbury and Evans, 1848. Rpt. in Charles Dickens's Christmas Books, ed. Michael Slater. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1971, rpt. 1978. II, 235-362, 365-366.

Patten, Robert L. Dickens, Death, and Christmas. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2023. 344 pages. ISBN 978-0-19-286266-2.

Created 7 February 2024